A young man from the country realizes his dream by joining his older brothers in the big city and sharing with them great adventures. But soon the dark side of life in a boom town destroys his dream, and he goes back to the country injured in body and spirit. When someone tries to kill one of his brothers, he is obligated to return. When another brother is killed, the hope for a bright future is replaced with rage. Hate consumes him, and he loses all feeling for himself or others. He soon kills — or helps to kill — men believed to have been involved in his brother’s death, and a warrant for his arrest is issued. He drifts from town to town. Trouble follows — trouble brought on by the emptiness in his heart, trouble that leads to his death by gunfire.

Sound like the story line of some old B western? Maybe so. But it was also the life of Warren Baxter Earp.

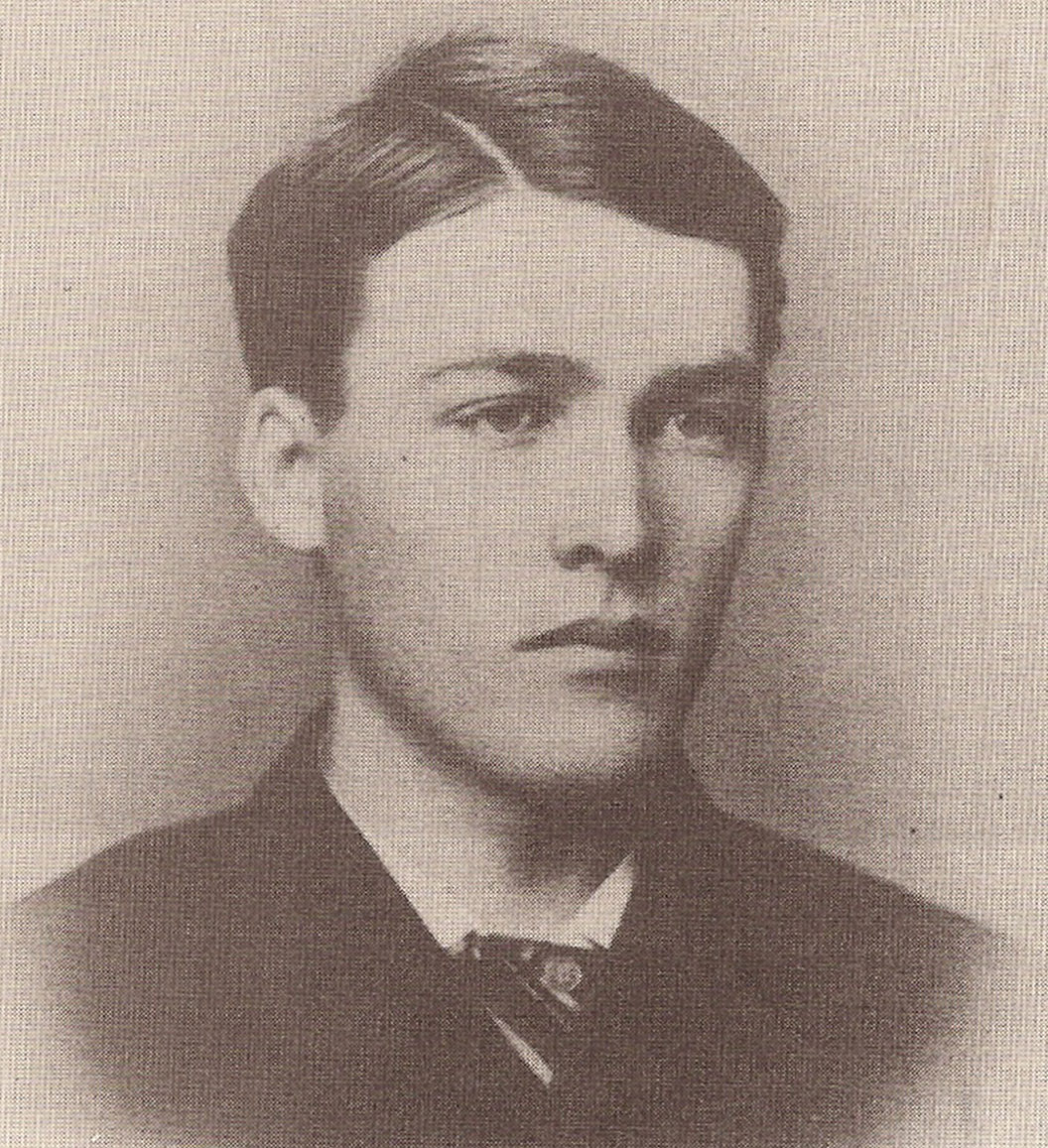

Warren was born in Pella, Iowa on March 9, 1855, to Nicholas and Virginia Earp. The youngest of six brothers, he was born 18 years after the birth of the oldest, a half-brother named Newton. He was told of a half sister born to Nicholas’ first wife, Abigale, but the sister had died at birth. A full sister, Martha, had died when he was about 1 year old. He did have two younger sisters, Virginia and Adelia, but Virginia had died in 1861 when Warren was still a child. He was nearly four years younger than his nearest brother in age, Morgan. The older brothers were James, born in 1841; Virgil, born in 1843; and Wyatt, born in 1848.

By the time he was in his teens and his brothers had gone off, only Warren was at home in Colton, Calif., to care for and to be cared for by his parents. Years later, Virgil’s wife, Allie, would describe Colton as ‘a sleepy little town out on the desert from Los Angeles, and not far from San Bernardino — just a stretch of cactus with some trees along the creek.’ There, Warren grew to manhood, knowing full well that his brothers were off doing more exciting things than working the land and tending bar at their father’s saloon.

Finally the chance came to fulfill his dreams. Word reached Warren that brothers James, Wyatt, Morgan and Virgil all at a fast growing silver-mining town in Arizona Territory. So in 1880 he went to Tombstone, where he moved in with Virgil, a deputy U.S. marshal and chief of police, and Allie. Bowing to his brother’s desire to ware a badge and gun, Virgil would sometimes allow Warren to guard prisoners, deliver papers and join posses.

In July 1881, word reached Virgil that a herd of cattle stolen in Mexico was being moved from the ranch of a suspected rustler named Newman ‘Old Man’ Clanton. A posse was formed to investigate, and Warren was a member of that posse. Although there has been no official proof (even Wyatt Earp later disclaimed it), some researchers believe that the lawmen caught and killed most of the rustlers, including Old Man Clanton. Warren is believed to have been injured during that gunfight. According to a letter written by his sister Adelia, Warren soon returned to Colton and stayed with her,’suffering from a wound he received in a fight with rustlers on the Mexican border.’

It was while Warren was recuperating that his brothers — Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan — and Doc Holliday shot it out with the Clantons and McLaurys in the famous October 26, 1881, gunfight near Tombstone’s OK Corral.

On December 28, men identified as Ike and Phin Clanton, Frank Stillwell, Johnny Barnes, John Ringo, Hank Swilling and Pete Spence, attempted to assassinate Virgil while he walked across Allen Street. Although Virgil survived, he lost most of the use of his left arm. Most of the shooters were arrested, but acquitted on technical grounds. Wyatt was appointed U.S. deputy marshal. Upon hearing about Virgil’s fate, Warren returned to Tombstone. He again moved in with Virgil, and Allie and helped with Virgil’s care.

Killers struck again on March 18, 1882. Wyatt was watching Morgan play pool with Bob Hatch when two shots shattered the glass in the back door of Hatch’s Saloon and Billiard Parlor on Allen Street. The first shot severed Morgan’s spine and then passed through his body and lodged in the leg of a bystander. The second shot hit the wall near Wyatt’s head. Warren was notified of the shooting and rushed to Morgan’s side. But there was nothing he could do. Warren’s dream had become a nightmare.With Warren’s help, Wyatt quickly made arrangements to send Morgan’s body, accompanied by Virgil, to Colton by train. The rest of the Earp family, including their wives, boarded the train in Contention, Arizona Territory. Feeling that the Earps were still in danger, heavily armed friends, including the ever-present Doc Holliday, also boarded to protect them.

A coroner’s jury had named Pete Spence, Frank Stillwell, Joe Fries (real name Fredrick Bode) and a man known as Indian Charlie as Morgan’s killers. En route, the Earp party got word that Ike Clanton, Stillwell and others were awaiting them in Tucson, a regular stop for the California-bound train. Once in Tucson, Warren, Wyatt, Holliday and three other men got off the train fully armed. Stillwell was spotted by a member of the Earp group. The next morning, March 21, Stillwell’s bullet-filled body was found near the tracks. Most witnesses were a bit vague on who they saw pursuing Stillwell. The one exception was Ike Clanton. He said, ‘Frank Stillwell was walking down the track followed by Wyatt Earp, Warren Earp, Doc Holliday, [Sherman] McMasters, [Turkey Creek Jack] Johnson.’ Murder warrants were issued by Sheriff Bob Paul for the five men named by Clanton. Warren Earp was now, in the eyes of the law, a criminal.

Warren, Doc, Wyatt and their friends hurried back to Tombstone for provisions they would need to pursue the so-called Clanton gang. By the time they arrived, Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan had received the warrants and tried to arrest them. They refused arrest and rode out. Behan soon formed a posse that included Ike and Phin Clanton. According to the Tombstone Epitaph, ‘Sheriff Bob Paul refused to go after the Earps, because the posse selected by Behan was notoriously hostile to the Earps, and said that a meeting with them meant blood, with no probability of arrest.’

Three men died at hands of the Earp party. Florentino Cruz, who supposedly admitted holding the horses when Morgan was killed, was shot down at Pete Spence’s wood camp in the Dragoon Mountains on March 22. A couple days later Curly Bill Brocius and Johnny Barnes paid the ultimate price when they and others attempted an ambush on the Earp party near Iron Springs. It isn’t known for sure if Warren helped shoot any of those three men.

When the Earps learned that they were being pursued by a large posse that would surely kill them on sight, the group disbanded and left Arizona Territory. Warren, Wyatt and Doc eventually ended up in Denver, Colo. The territorial governor’s attempt to extradite them failed.

The Earps decided to go to Colton, Calif., but Doc Holliday elected to stay behind in Colorado (tuberculosis killed him in Glenwood Springs, Colo., on November 8, 1887). Wyatt and his wife, Josie, didn’t stay long in Colton. Wyatt’s post-Tombstone adventures, shared with Josie, saw him mostly prospecting and gambling as far north as Nome, Alaska. He didn’t die until 1929.

Warren Earp returned to Colton a bitter, disillusioned man. His mind was filled with pain, fear and hate. He was apparently at a loss about what to do next. The bottle became his best friend, the saloon his home. He would lash out at anyone he perceived to be an enemy. The press picked up on some of his barroom encounters, at first treating them rather lightly due in part to the fact that his father was at the time a well-respected judge. One newspaper report stated: ‘Late last night in the M & O Saloon on Third Street a Mexican named Juan Bustamante and Warren Earp engaged in the pleasant pastime of cracking each others heads – – they both gave bail.’

The incidents grew more frequent and more violent. The Silver City Enterprise, reported on June 8, 1883: ‘Warren Earp, one of the most quarrelsome of the Earp brothers, recently got into a shooting scrape at Colton, California — with a Mexican named Belarde. The Mexican was arrested.’ The San Bernardino Index later reported that Warren attacked a waiter in a restaurant and cut him with a broken bottle. That time he was arrested and fined $25.00. On February 27th, 1885 the Enterprise said that Warren was arrested for’shooting his partner’ but did not give details or what came of it.

After that incident, Warren seemed to have stayed out of trouble for a while. No doubt he was encouraged to keep his nose clean by his father and his brother Virgil, who was now a lawman again. Warren tended bar at his father’s saloon and drove a coach. He was not mentioned in any newspaper reports until August 26, 1893. The Weekly Chronicle reports that ‘during Virgil’s absence,’ Warren Earp stabbed a man named Steele in the back. The man survived and Warren was acquitted.

The stabbing may have been too much for Judge Nicholas Earp. He apparently sent Warren packing. The wayward son took an unnamed woman with him. They were in Yuma, Arizona Territory, late in 1893, even though there was apparently a warrant for his arrest for murder and there were still people who wanted the Earps dead. Soon after their arrival in Yuma, the woman left Warren. Warren blamed their separation on a professor Bahrens. On November 9, 1893 Warren at first threatened to kill the professor and throw him off a bridge. But then Warren said that if Bahrens paid him, he would spare his life and leave town. Bahrens paid up, so Warren let him go. Warren was soon arrested for attempted murder, extortion and disturbing the peace. Unable to make bail, he was jailed. On November 25, he was tried. The attempted murder charge was dropped due to a technicality; he was fined on the other charges and made to promise that he would leave town.

Warren drifted for a while until he arrived in Willcox, Arizona Territory on August 3, 1894. He registered at the Willcox House and went looking for an old friend of the family, Colonel Henry Clay Hooker; the president of the Cattlemen’s Association. Hooker owned a huge ranch called Sierra Bonita in the Sulphur Spring Valley, not far from Willcox, as well as a smaller place, called Hooker’s Hot Springs in another part of the state. Hooker put Warren to work as a detective for the association and provided him a place to live.

Warren’s only noted brush with the law during that period came in 1896, when he took a $20 bill from a Monte table and was jailed for eighteen days for petty larceny. He was still working for Hooker in 1900, the year of his death. The true reason for his death may never be known. There are two accounts of events leading to it, both by supposed eyewitness.

One account was recorded by a reporter named E. F. Schaff on July 31, 1971, and was based on an interviewed with 94-year-old Bill Whelan, Sr., who claimed to have been a Hooker cowhand and a friend of Warren’s. Whelan, whose father had been a foreman at the Sierra Bonita, said that he, Warren and several ranch hands came into Willcox on July 4, 1900 to celebrate the holiday. They were joined by workers from Hot Springs, including Johnny Boyett and a lady friend, Mary Sweeney. Warren asked her to ‘quit’ Johnny and join him. She refused, and Warren and Johnny argued. Warren challenged the other man to a duel, but Boyett seemed willing to let it pass, blaming the ‘fuss’ on all of them being drunk.

On July 6, Warren Earp, Bill Whelan and others had gathered for a drink before going back to the ranch. When Johnny Boyett came in, Warren jumped up and said ‘Johnny, get ready, we’ll fight it out.’ Being unarmed, Boyett went to the Willcox House, got the owner’s gun and returned to the saloon. Warren wasn’t there. Boyett went to the bar and propped his elbow on it with the gun pointed up. When Warren entered, he lunged for Boyett, but Boyett shot him dead. It was judged self-defense. Warren, according to Whelan’s recollection, was buried on the day he died. Whelan added that Boyett soon disappeared.

Some historians pass this off this account as the ramblings of an old man whose memory played tricks on him. The second account, though based on testimony given right after the shooting, leaves questions unanswered to this day about the erratic behavior of the two principals. An inquest was held the same day of Warren’s death by W.F. Nichols, justice of the peace and ex-officio coroner of Cochise County. Bill Whelan apparently was not called to testify, but O.W. Hayes and saloon owner Henry Brown did testify.

Hayes testified that John Boyett and Warren Earp came into the Headquarters Saloon together about one o’clock on the morning of July 6. He soon heard Warren say: ‘You was paid $150 at one time to kill me. Go get your gun. I have got mine.’ Boyett, according to Hayes, then walked out proclaiming that he didn’t want any trouble. Warren probably thought he had seen the last of Boyett and walked into an adjoining restaurant. But soon Boyett came back into the saloon with a gun in each hand. ‘Where is the SOB?’ he yelled. When Warren came to the open door joining the restaurant and saloon. Boyett fired two shots at him but missed. Warren went out the restaurant’s front door, and Boyett walked to the center of the saloon toward that door. For some reason, Boyette fired two more shots into the floor.

Henry Brown testified that Warren then entered through a side door to the saloon. He opened his coat and vest and, advancing on the man who had just tried to kill him, said: ‘I have not got any arm. You have a good deal the best of this.’ Boyett, with guns still pointing at his adversary, kept telling him to stop. But when Warren got to within about 10 feet of his foe, the fifth shot was fired. Warren Earp fell face down, dead. M.J. Nicholson, a local physician and surgeon, testified that he had done an autopsy and that Warren was killed by a bullet that entered from the front and ranged from left to right and obliquely downward, passing through the heart. As a result of the inquest, Judge Nichols chose not to indict Boyett. Furthermore, for some reason he didn’t explain, he believed no jury would convict Boyett and a trial would therefore be a waste.

Whatever was said that day, it seems clear that Warren Earp had provoked John Boyett into a killing rage. Although Warren had said he had a gun, according to Hayes’ testimony, he most likely was unarmed, as Henry Brown testified. In any case, it seems that Warren was again trying to live up to the Earp name. He had tried to frighten Boyett into running, and when that failed, he had courageously approached Boyett in hopes of buffaloing and disarming him — something Wyatt or Virgil would have done.

Some historians believe that Virgil Earp and/or Wyatt Earp tracked down Boyett and killed him, largely because Josie Earp later recalled that her husband and Virgil went to Willcox after Warren’s death. More likely, though, Wyatt Earp was in Nome, Alaska, when he got news about Warren, and he remained there that whole summer.

Today Warren Earp lies in an abandoned cemetery on a hill near Willcox, his grave overgrown with weeds. His resting place is noted only by a wooden plaque marked with a cross, his name and the day he died. A Warren Earp Memorial was unveiled and dedicated on Saturday, July 8, 2000, in Wilcox, Ariz., as part of ‘The Warren Earp Shooting, 100 Years Later,’ an event that also included a guided walking tour of related locations, a re-enactment of the shooting and a book signing involving several Earp researchers.