James Michael Curley’s first arrest came in 1903, when he was a 28-year-old Massachusetts state legislator. He was charged with conspiring to “defraud the United States” for taking the federal Civil Service exam while pretending to be one of his constituents, an Irish immigrant who hoped to become a mailman.

“He couldn’t spell Constantinople,” Curley explained, “but he had wonderful feet for a letter carrier.” Sentenced to two months in jail, Curley responded by running for Boston alderman on the slogan, “He did it for a friend.” He won easily.

Curley’s second arrest came in 1943, when he was a 68-year-old congressman charged with mail fraud in a scheme to extract bribes from companies seeking federal contracts. “I’m being persecuted,” he said, by “Communists and radical reformers.” Under indictment in 1944, he won re-election to Congress. Awaiting trial in 1945, he was elected mayor of Boston. Convicted in 1946, he served as mayor while serving time in a Connecticut prison.

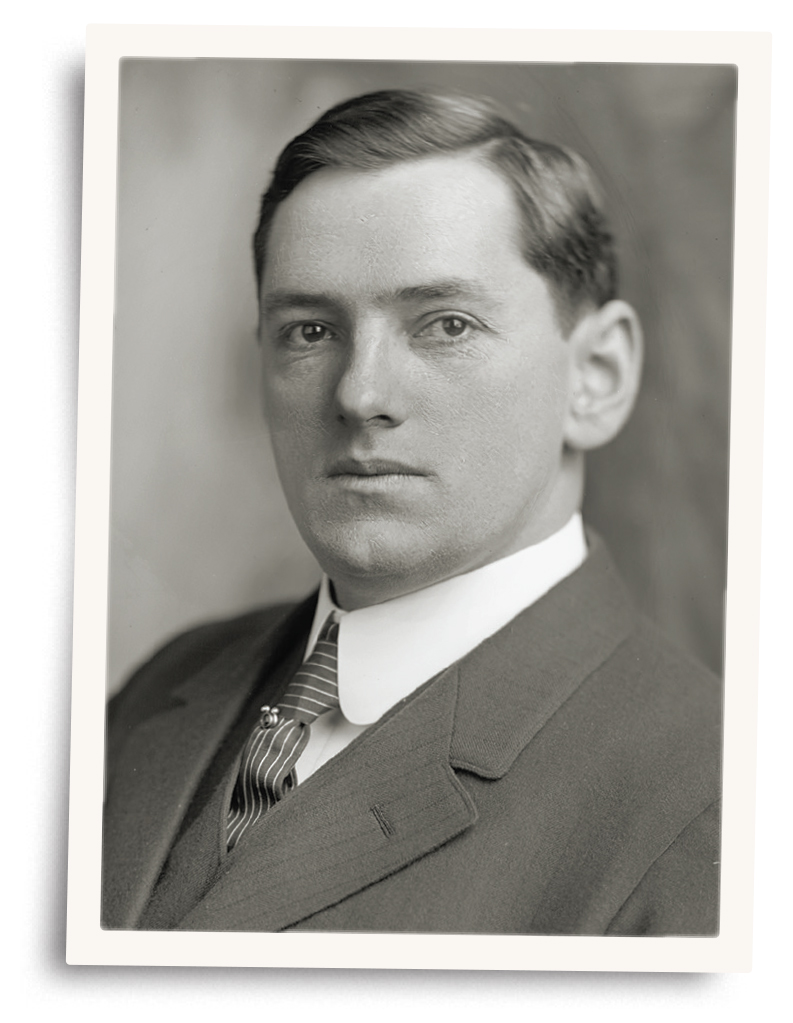

In the 40 years between sojourns in the hoosegow, Curley was elected mayor of Boston four times, governor of Massachusetts once, and congressman four times. For half a century, he dominated the state’s politics with his pungent wit, his orotund oratory, his Machiavellian shrewdness—and the support of working-class Irish Americans who saw him as the embodiment of their hopes. And he lived to see himself portrayed as a lovable rogue in the best-selling novel The Last Hurrah, and played by Spencer Tracy in the 1958 movie version.

Son of Irish immigrants, James Michael Curley was born in Boston in 1874. His father, a laborer, died when James was 10. To help his mother, a scrubwoman, support the family, James began working at 11, selling newspapers. He quit school at 15 to work in a piano factory, then finished high school at night, while spending his days delivering groceries by horse and wagon.

Eager to enter politics, he volunteered to run social activities at a Catholic church and worked for the Ancient Order of Hibernians—thus building a political base among the Boston Irish. In 1899, he won a seat on the city’s Common Council, running as a Democrat, the party of Boston’s immigrants, and entertaining Irish voters by mocking the “Boston Brahmin” elite as old, weary has-beens with “dogs and no children.”

He created a political organization, “The Tammany Club,” named after New York’s Democratic machine, and organized picnics and Christmas parties for the poor. He did favors for constituents—providing a meal or a job and, as we’ve seen, taking a Civil Service exam “for a friend.” He recorded each favor in a notebook, expecting recipients to thank him with their votes. And they did, electing Curley state representative in 1902, alderman in 1904, and congressman in 1910.

Three years later, he was elected mayor, using a trick so outrageous it became legendary. Curley learned that the incumbent mayor, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald—the grandfather of President Kennedy—was having a fling with a barmaid nicknamed “Toodles.” A Curley crony informed the mayor’s wife of the affair in a letter, demanding that Fitzgerald withdraw from the race. But Fitzgerald refused, so Curley announced his plan to deliver a public lecture titled “Great Lovers in History: From Cleopatra to Toodles.” Fitzgerald quit and Curley won.

As mayor, Curley exhibited the political philosophy that would continue all his life—a proto-New Deal two decades before FDR’s election. Calling himself “the mayor of the poor,” he spent city money hiring workers to pave roads, expand the city hospital and build schools, sewers and playgrounds. He cut the pay of the highest-paid city workers, and raised the pay of the lowest. Recalling his mother’s years scrubbing floors on her hands and knees, he famously issued long-handled mops to City Hall’s scrubwomen, declaring that no woman should go down on her knees except to pray.

“Government was not created to save money and to cut debt, but to take care of people,” he said. “That’s my theory of government.”

He did take care of people—but not nearly as lavishly as he took care of himself. Curley was as crooked as a pretzel. He forced city employees to fund his campaigns by purchasing tickets to Tammany Club dinners. He signed sweetheart deals giving city contractors huge profits, provided that they split the booty with him. He hardly bothered to hide his graft. Bostonians watched as construction companies with lucrative city contracts built Curley a 21-room, 10,000 square foot, neo-Georgian mansion with marble fireplaces—and charged him next to nothing.

“Even his core voters knew Curley was dishonest,” Jack Beatty wrote in his excellent Curley biography, The Rascal King. “For many Bostonians, his good works would ever stay their dudgeon at his bad deeds.”

In 1934, Curley was elected governor. As he had done in Boston, he hired the unemployed to build roads and schools. But he also purged the state Finance Commission, which was investigating corruption in Boston’s government, a subject Curley preferred to keep hidden. He fired one member, appointed another to a judgeship, and replaced both with toadies uninterested in investigating their boss.

For lesser jobs, Curley appointed cronies. His chauffeur got a state job; so did his gardener. A man who had served time for forgery was hired as an auditor. Curley also displayed unusual sympathy for prisoners, pardoning or paroling 254 on Christmas Day 1935—an act of mercy inspired by generous gifts to the governor from the prisoners’ attorneys.

Soon, newspapers and magazines began attacking Curley’s corrupt regime. “Governor Curley appears to be suffering now from delusions of grandeur,” a Springfield Union editorial charged, “and sees himself becoming dictator of this Commonwealth a la Huey Long.”

Realizing he couldn’t win re-election in 1936, Curley ran for the Senate instead, but he was trounced by Republican Henry Cabot Lodge. In 1937 and 1941, he ran for mayor of Boston but lost both races.

He seemed finished, an aging relic of a bygone era. But in 1942, Boston voters elected him to Congress, and in 1946 they elected him mayor. After spending five months of his term in federal prison, he ran for mayor three more times, though never winning again.

He was 82 and sickly in 1956, when Edwin O’Connor published The Last Hurrah, his novel about a very Curley-esque politician. Curley loved the book but sued to prevent release of the movie version, claiming it violated his privacy. The producers responded that they had already paid him $25,000 for his permission. Curley denied ever receiving their money or giving his permission. Anxious to avoid a lengthy court battle and eager to premier the movie in Boston, the studio paid Curley another $15,000.

That was his final scam, his last hurrah. When he died, two months later, 100,000 mourners filed past his coffin.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.