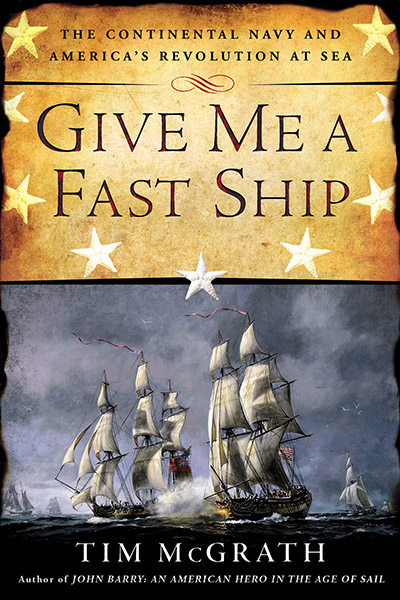

Give Me a Fast Ship

The Continental Navy and America’s Revolution at Sea

By Tim McGrath. 560 pages. NAL Caliber, 2014. $26.95.

Reviewed by Joseph F. Callo

YES, THERE REALLY WAS A NAVAL COMPONENT to the American Revolution, but it was by no means well organized or brilliantly executed. There was incompetence, self-interest, and plain bad luck among the Continental Navy’s officers and their civilian leaders, but there was also matching skill, courage, and high ideals on both the civilian and military sides of the American equation.

To bring a better understanding of that period, Give Me a Fast Ship goes beyond a “spotlight” treatment of major events, offering instead a series of mini-stories that illuminate the nitty-gritty of colonial America’s desperate struggle at sea. In the process there is strong emphasis on the people who drove the naval proceedings. George Washington, John Adams, Robert Morris, John Paul Jones, and John Barry are among those with leading roles in this narrative. Washington procured and deployed the first ships that sailed in the cause of the American colonies. Morris cobbled together the financing for the war. Adams pushed through the legislation that established the Continental Navy and authorized its initial construction of ships. Jones projected naval power against the British homeland at a tipping point in the war. And Barry was among the first Continental Navy captains.

Important themes are woven through the scores of separate stories related by McGrath. One of the most compelling has to do with the often troublesome working relationships between the Continental Navy captains and their civilian leaders. John Paul Jones’s relationships with Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee demonstrated the good and the bad of those associations. The current relevance of that issue—and others, such as the challenge of funding an effective navy, recruiting and retaining experienced seamen, and the ever-present role of politics in shaping naval policy—are also there to contemplate.

Given the difficulties of challenging Britain, the world’s greatest navy of that time, an inevitable question arises: What motivated those who doggedly fought at sea against such long odds? McGrath gives us a hint on his first page, when he describes the motivation driving the participants of that informal “naval action” called the Boston Tea Party: “To begin with, they hardly paid any taxes. But it was not the amount that angered these New Englanders. It was the idea of the tax itself; the act of a governing body demanding revenue from fellow countrymen who…did not possess the right to be represented among the lawmakers who levied the tax.”

The American Revolution wasn’t about borders, monarchs’ rights of succession, religious differences, or gold. It was about ideas—concepts such as self-determination and the inalienable rights of the governed. It was dedication to ideas and ideals that sustained those who prosecuted the naval component of the American Revolution. John Paul Jones put it nicely in a letter to Robert Morris: “The situation of America is new in the annals of mankind. Her affairs cry haste, and speed must answer them.”

Joseph F. Callo is a retired U.S. Navy rear admiral who has written extensively about Lord Nelson, John Paul Jones, and the formation of the United States Navy.

.jpg)