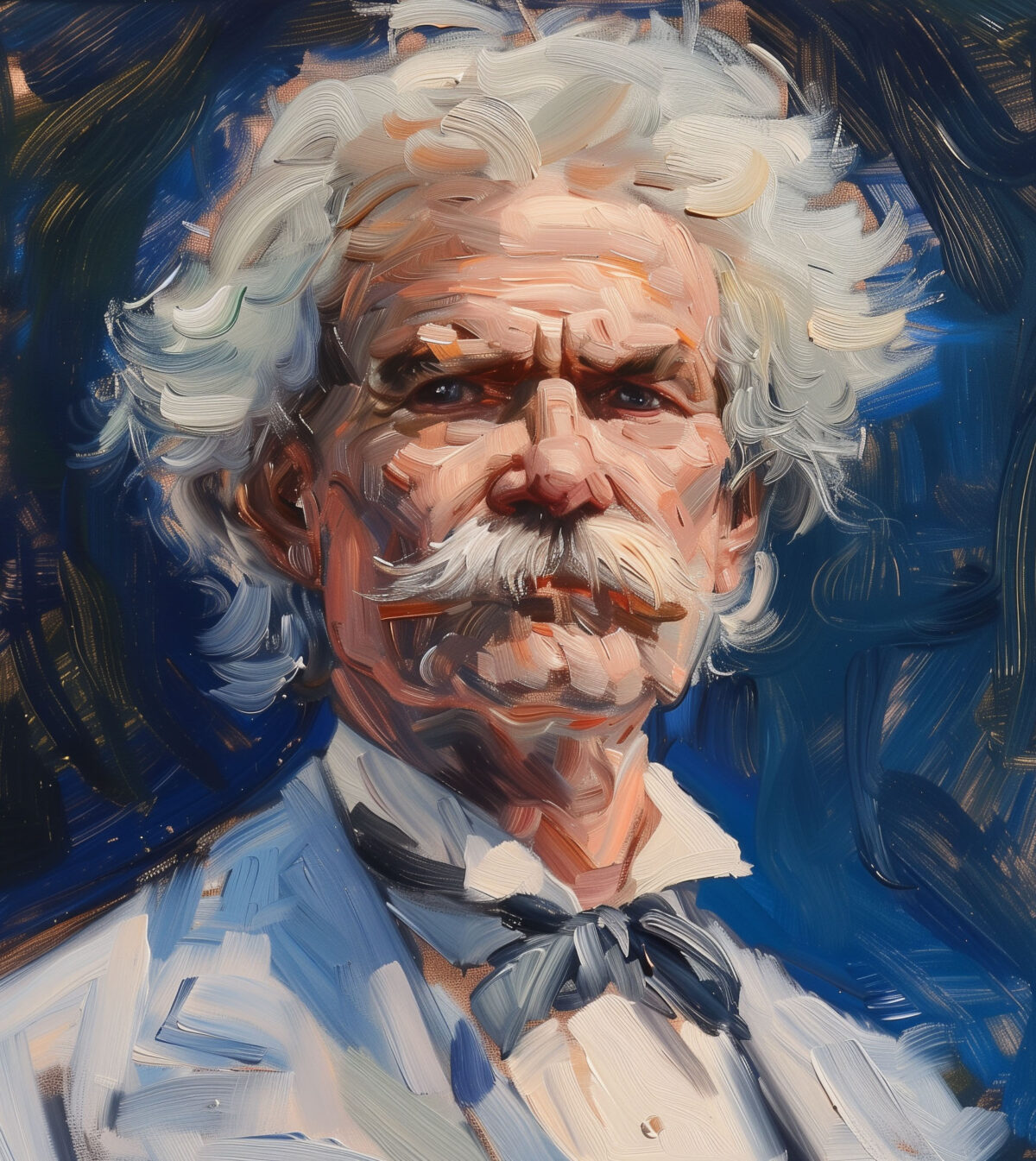

“You have heard from a great many people who did something in the war; is it not fair and right that you listen a little moment to one who started out to do something in it but didn’t?” wrote Mark Twain in his semi-fictionalized wartime account, titled “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed.”

“Thousands entered the war, got just a taste of it, and then stepped out again, permanently,” he continued. “These, by their very numbers, are respectable and therefore entitled to a sort of voice, — not a loud one, but a modest one; not a boastful one but an apologetic one. …”

In the summer of 1861, the former riverboat pilot went to war, according to the St. Louis Magazine, on a small yellow mule carrying a valise, a carpetbag, two gray blankets, a homemade quilt, a squirrel rifle, 20 yards of rope, a frying pan and, perhaps most importantly of all, an umbrella.

The 25-year-old Missourian, alongside 14 other idealistic young men, answered Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson’s call of 50,000 militia to defend their home state.

The few, the band of brothers, called themselves the Marion Rangers, with Twain entering their ranks as a second lieutenant.

Twain, whose real name was Samuel Clemens, had grown up amid slavery in the South. His father had owned slaves. So had his neighbors. In 1860 Twain had voted for John Bell in the presidential election, who, although a Tennessee slaveholder, had opposed secession.

Twain’s vote was seemingly a vote for the status quo he had grown up around.

But as the war approached Missouri, Twain decided to take a stand — albeit a brief one.

In all, the famed author’s two-week stint as a soldier in the Civil War largely amounted to him larping as a Confederate.

“The first hour was all fun, all idle nonsense and laughter. But that could not be kept up,” Twain wrote in “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed.”

“The steady trudging came to be like work; the play had somehow oozed out of it; the stillness of the woods and the somberness of the night began to throw a depressing influence over the spirits of the boys…”

As the men slogged farther into the woods around Hannibal, Marion County — seemingly with no real plan of action or direction — the men began to quibble over whose job it was to cook. No one seriously took orders from their “chain of command,” as most didn’t even know what the ranking structure consisted of.

After Twain ordered a subordinate to feed his mule the man retorted that he didn’t reckon “he went to war to be a dry-nurse to a mule.” Twain himself mused that he “believed that this was insubordination, but [he] was full of uncertainties about everything military, and so [he] let the thing pass.”

To make matters worse, it rained continuously, according to accounts, adding to the malaise of the already downtrodden men.

Cosplaying at war, the Marion Rangers would retreat at the merest mention or sign of Union troops in the area.

“I knew more about retreating than the man that invented retreating,” Twain quipped of his experience.

The men tried to retreat, “only to realize that they had no idea how to retreat,” according to a report by The Great Falls Tribune. “Their paper command structure collapsed, and for two weeks they stumbled and bumbled their way around the area, until at last they were threatened by a real Yankee military force commanded, as they later learned, by colonel and soon to be general Ulysses S. Grant.”

By then, the 25-year-old had had it with his little war and slipped away to his sister Pam’s home in St. Louis. Soon after, Twain’s brother, Orion Clemens, offered him an opportunity to go west that summer to Nevada. Twain readily accepted, summarily ending his war.

Ironically, 20 years after Twain’s brush with the Confederacy, it was he who suggested to the ailing Grant that the former Union general-turned-president write his memoirs.

Grant, who was slowly dying of throat cancer, had watched as his entire nest egg disappeared after the collapse of Grant & Ward, the investment firm into which Grant had put his entire life’s savings.

Motivated to provide for his beloved wife, Julia, as his inevitable death loomed, Grant got to writing.

Twain had been instrumental in the formation of Charles L. Webster & Company in 1884. Though it bore the name of his nephew through marriage, Twain was its de facto head, and in February 1885 the company made Grant an offer — Grant should get as much as a 20 percent royalty, or alternatively, 70 percent of the net profits, according to historian John Vacha.

Julia was to be well taken care of and, thanks to one former Marion Ranger, the “Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant” became, next to the Bible and “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” the most visible volumes in 19th-century American homes — at least, writes Vacha, those outside the South

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.