In 1884 Ulysses S. Grant was bankrupt and battling terminal cancer. Then Mark Twain made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

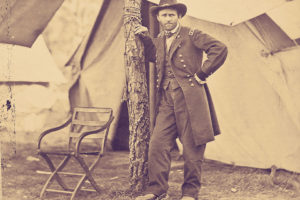

IN THE SPRING OF 1885, A DIMINISHED FIGURE WRAPPED IN A SHAWL, a knitted cap pulled over his brow, toils in a brownstone on East 66th Street in New York City. His right hand, trained to wield a sword, pushes a pen across curling sheets of paper. Twenty-one years earlier, in his final campaign against Robert E. Lee in Virginia, Ulysses S. Grant had informed Washington that he proposed to fight it out on that line if it took all summer. Now, engaged in a final campaign to complete his memoirs, he knew he didn’t have all summer; this time he might not even make it through the spring.

As Grant would explain in his preface, he had long resisted the frequent exhortations from friends that he write his memoirs. One of the first had come from the author Mark Twain, who raised the suggestion on a visit to Grant’s New York City office in 1881. The former president responded at the time that he had neither need for extra income nor faith in his writing ability. Three years later publisher Richard Watson Gilder solicited Grant for contributions to a prospective Battles and Leaders of the Civil War series in his Century magazine. Once again Grant displayed indifference to the idea.

Two stunning developments soon changed Grant’s attitude about turning author. The first came only months after Gilder’s offer: On May 6, 1884, Grant & Ward, the investment firm into which Grant had put his entire nest egg, collapsed. As with the scandals that had marred his presidency, Grant had been unwittingly victimized by an unscrupulous partner, Ferdinand Ward, who ran the company as a Ponzi scheme. Reduced, as he put it, to “living on borrowed money,” Grant was more receptive when Gilder renewed his pitch for Century’s Civil War series.

For $500 an article, Grant agreed to provide Century with his accounts of four battles and campaigns: Shiloh, Vicksburg, the Wilderness, and Appomattox. (Chattanooga would later be substituted for Appomattox.) He began writing at the family’s summer retreat in Long Branch, New Jersey, and submitted a draft on Shiloh in July 1884. It was admirably straightforward in style, like a general writing an after-action field report—but maybe a little too much so. Editor Robert Underwood Johnson came to see Grant in Long Branch to suggest the infusion of more color and personality.

Judging from the result, Grant employed Johnson’s advice to good effect. Shiloh “was a case of Southern dash against Northern pluck and endurance,” he wrote. He described “an open field, in our possession on the second day, over which the Confederates had made repeated charges the day before, so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.” Perhaps in answer to criticisms that his forces had been caught unprepared and nearly routed, Grant said that there had been “no hour during the day when I doubted the eventual defeat of the enemy.” When the article appeared in print several months later, it brought the Century an unprecedented sale of 220,000 copies.

WORKING ON THE BATTLES AND LEADERS SERIES SEEMED TO GIVE GRANT INCREASED CONFIDENCE in his skills as a writer. He moved on to Vicksburg but gave some thought to the campaign’s place in the overall progress of the Civil War. It came in the wake of the 1862 elections, in which the Republicans had sustained heavy losses in Congress. Enlistments had fallen off to such an extent that the North had to turn to conscription to fill the ranks of its armies. The main Union force in the West appeared to be bogged down across the Mississippi from the Confederate citadel of Vicksburg, with little chance of storming its bluffs. As Grant saw it, to begin afresh from a different approach might have been fatal to Northern morale. “There was nothing to be done but to go forward to a decisive victory,” he wrote. So the Union army marched down the western bank of the Mississippi, and the navy ran the Confederate batteries at night to ferry Grant’s troops across the river below Vicksburg. When the Confederates moved to cut off his supply line, they discovered that Grant had no supply line, having abandoned it more than a week before to live off the land.

As he warmed to the task of writing, Grant began to think seriously about a memoir of the entire war. Presumably he started filling in the lacunae left by his Century pieces, mentally if not yet on paper. He would begin with the years of preparation, before 1861, including the apprenticeship of service in the Mexican War. Historians would become familiar with his judgment of that conflict as “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” Somewhat less familiar is the relationship Grant drew between the Mexican and the Civil Wars. “The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war,” he asserted. “Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.”

Grant’s ideas about expanding his efforts into a full-blown memoir received a sharp prod with the onset of his second reverse. It was foretold within a month of the Grant & Ward debacle in May 1884, when a simple bite into a peach sent Grant into a paroxysm of pain. He put off seeking medical advice until the family’s return from Long Branch to New York in the fall. Grant saw a specialist there, in early November, who diagnosed terminal cancer of the throat. Grant had undertaken the Century articles as a means of income for him and his family. Now the need to provide for his widow and children after his death hastened Grant’s determination to complete the memoirs. He had begun discussing the project with Gilder’s Century Company during the summer. After the diagnosis Grant proffered a verbal commitment, and the Century tendered him a draft contract offering royalties of 10 percent. Still engaged in completing the magazine articles, Grant put off signing the contract but hired one of his former military aides, Adam Badeau, as a research assistant.

ABOUT THIS TIME, IN 1884, MARK TWAIN REENTERED THE PICTURE. He called on the ailing general several times that fall, finding him in deteriorating condition but steadily at work, writing through his pain. When Twain learned the details of the Century offer, he became indignant, insisting that a memoir by someone of Grant’s stature would sell far more than Century’s projected 25,000 copies. Grant should get as much as a 20 percent royalty, he said, or alternatively, 70 percent of the net profits.

Twain knew what he was talking about, not only as a fellow author but as a fledgling publisher. Dissatisfied with his former publisher, Twain had been instrumental in the formation earlier that year of Charles L. Webster & Company. Though it bore the name of his nephew through marriage, Twain was its de facto head, and in February 1885 the company made Grant an offer on the terms Twain had suggested. Grant hesitated at first, out of a sense of obligation to the Century Company, but Twain countered that scruple with a reminder that Twain had actually been the first to suggest that Grant write his memoirs. Conceding Twain’s point and considering the superior terms of his offer, Grant signed with Webster on February 27. Out of concern that Twain not lose money on the deal, he opted for 70 percent of the profits.

While Grant returned to recounting his campaigns, Twain launched one to sell Grant’s book. He prepared to market it the same way his own books had been sold, by means of a nationwide subscription campaign. At the time this was the main alternative to the traditional “book trade”—individual stationery and bookshops centered in the country’s cities and towns. The leading literary critics of the day by far preferred books issued by the major trade publishers, rarely if ever condescending to review those peddled to the masses by what amounted to traveling salesmen or drummers. Twain’s first book, The Innocents Abroad, sold 80,000 copies by subscription in 1869–1870 but might have passed unnoticed had a young reviewer named William Dean Howells not deemed it worthy of high praise in the highbrow Atlantic Monthly. After that, Twain had no trouble being noticed, and his new publishing company undertook a subscription campaign to sell the book that would be acknowledged as his masterpiece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

No matter how it was sold, Twain realized that a book bearing the name of U. S. Grant would gain not only the notice of critics but entry into average American households. As Twain biographer Ron Powers put it, “The people who opened their doors to subscription booksellers burdened with ‘sample books’ for show-and-tell, and order forms, and illustrations…and binding samples, these were the Great Emerging American Middlebrow.” In this sense, subscription publishers may be seen as the 19th-century precursor of the 20th century’s Book-of-the-Month Club. And as Twain hoped to do with Grant’s Civil War memoirs, the Book-of-the-Month Club would place sets of Winston Churchill’s Second World War memoirs on the shelves of a million American homes.

Twain’s campaign was military in nature to the extent that it enlisted Civil War veterans as salesmen. Webster & Company employed 16 general agents to direct some 10,000 canvassers—a host nearly equivalent to one of Grant’s army corps. Those who were veterans were advised to wear their G. A. R. badges, since more likely than not the households they called on harbored a fellow veteran. Each was handed a 37-page manual containing tips (or tricks?) of the trade specifically customized for the pitching of Grant’s memoirs.

Sample books and bindings in hand, they fanned out across the land like lines of Union skirmishers. The prototype of the book consisted largely of blank pages, since the text was still being written. Canvassers were instructed to appeal to the patriotic sentiments of prospects, speak of the financial straits of Grant’s family, and suggest the value of such a work as a family heirloom. By the beginning of May they had orders in hand for 60,000 sets.

WITH FINANCIAL SUCCESS ASSURED, THE MAIN QUESTION NOW was whether there would be a product to deliver. On March 1 the New York Times broke the news with the headline grant is dying, and reporters began a death watch on East 66th Street. At the end of the month it appeared that the watch might be over, as Grant underwent a fit of coughing and choking that made him think death was near. But in a few days he recovered and went back to work. A note early in the second volume explains that except for the chapters on the Wilderness Campaign, completed earlier for the Century magazine series, the remainder of the work was written after his health crisis of early April.

The Wilderness section contains some of Grant’s most vivid writing. He describes the hellish no man’s land in the three quarters of a mile of thick

undergrowth between the armies. “The woods were set on fire by the bursting shells, and the conflagration raged,” he wrote. “The wounded who had not strength to move themselves were either suffocated or burned to death….But the battle still raged, our men firing through the flames until it became too hot to remain longer.” In describing what followed, Grant for once deviated from his matter-of-fact realism to indulge in a passage of speculative drama featuring four of his generals that would capture the imaginations of future historians:

Soon after dark Warren withdrew from the front of the enemy, and was soon followed by Sedgwick. Warren’s march carried him immediately behind the works where Hancock’s command lay on the Brock Road. With my staff and a small escort of cavalry I preceded the troops. Meade with his staff accompanied me. The greatest enthusiasm was manifested by Hancock’s men as we passed by. No doubt it was inspired by the fact that the movement was south. It indicated to them that they had passed through the “beginning of the end” in the battle just fought. The cheering was so lusty that the enemy must have taken it for a night attack.

Twain’s involvement in the publication of Grant’s memoirs may have inspired him to write his highly fictionalized “Private History of a Campaign that Failed” for the same magazine series. Twain described the brief, inglorious career of the Marion Rangers, a pro-secession unit he served in, that was hastily recruited to resist Federal advances in Missouri early in the war. Twain and several others from his boyhood hometown of Hannibal, providing their own horses, weapons, and even clothing, engaged in a single short skirmish—an episode that proved to Twain he “was not rightly equipped for this awful business….I resolved to retire from this avocation of sham soldiership while I could save some remnant of my self-respect.”

There was a kicker at the end of Twain’s reminiscence. Notified that a Union colonel “was sweeping down on us with a whole regiment at his heels,” Twain’s tatterdemalion unit beat a hasty retreat, half of them, including Twain, never to return. Much later Twain learned the name of the colonel. “I came within a few hours of seeing him when he was as unknown as myself; at a time when anybody could have said, ‘Grant?—Ulysses S. Grant?,” he wrote. “I do not remember hearing the name before.’ ” Grant went on to Appomattox and apotheosis; Twain absquatulated to Nevada, well out of the war.

By the end of May Twain was able to show a draft of his “Private History” to Grant, who became its first reader. According to the author, Grant read it with pleasure. Twain frequently called at the East Side brownstone, offering words of encouragement as well as editorial advice. At Twain’s urging Grant switched from longhand to dictation, producing as many as 10,000 words in a single session. In April the New York World questioned his authorship, alleging that the work was being largely ghostwritten by Grant’s aide, Adam Badeau. Suspecting Badeau as the source of the rumor in a bid for a share of the profits, Grant dismissed his former aide, whose duties were assumed by his son Frederick. As the cancer eventually deprived him of the use of his voice, Grant reverted to longhand. In a note to his doctor, he later compared each additional page to “one more nail in the coffin.” Yet he also said, “I am thankful for the providential extension of my time to enable me to continue my work.” Twain believed it was Grant’s determination to finish his book that had kept him alive.

He soldiered on, writing through the remainder of the Virginia campaign. “Lee, by accident, beat us to Spotsylvania,” he wrote, explaining how one of Lee’s corps got there earlier than ordered because the fires in the Wilderness had prevented it from going into bivouac the previous evening. “But accident often decides the fate of battles.” It was a costly campaign, in which Grant willingly traded plentiful Union bodies for those of the irreplaceable manpower of the Confederacy. Even for him the price at times could be too high, as he confessed, “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made.”

It was Grant’s tenacious engagement of the Army of Northern Virginia that prevented Lee from reinforcing Confederate armies in the West. This opened the way for the sweeping Union campaigns that overran the rest of the South, particularly Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s in Georgia and the Carolinas. Grant gave Sherman full credit for the March to the Sea—its planning and its execution. He had confidence in his chief lieutenant as well as in his troops, whom he himself had commanded in the West—“sixty thousand as good soldiers as ever trod the earth; better than any European soldiers, because they not only worked as a machine but the machine thought.”

Nevertheless, Grant seemed to begrudge some of the fabulation associated with Sherman’s “bummers,” writing: “Many of the exploits of these men would fall under the head of romance; indeed, I am afraid that in telling some of their experiences, the romance got the better of the truth upon which the story was founded.”

Grant applied the same no-frills standard to himself, however, shooting down perhaps the most widely repeated story of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. “The much talked of surrender of Lee’s sword and my handing it back, this and much more that has been said about it is the purest romance,” he declared, and that was that.

By mid-June Grant had essentially finished the second volume. On the recommendation of his doctors, he was taken from the heat of New York City on the private car of railroad magnate William H. Vanderbilt, to the cottage of a friend at Mount McGregor in the Adirondacks. Unable to take food, his once stocky frame down to 125 pounds, Grant continued to put the final touches on the memoirs. Sitting on the front porch, he corrected proofs of the first volume and composed some new material for the second (“as many as fifty pages,” he told his doctor). Twain paid what was to be his final call at the end of the month, when Grant wrote the work’s preface, and the manuscript of the second volume was sent to Webster & Company on July 18. Grant died five days later.

VOLUME 1 OF THE PERSONAL MEMOIRS OF U.S. GRANT APPEARED AT THE END OF THE YEAR, followed three months later by volume 2. They were weighty tomes, illustrated with pictures of the young and the mature Grant, his birthplace in Point Pleasant, Ohio, and the McLean house at Appomattox, as well as many campaign and battle maps. Three months after publication of the first volume, Twain was able to present Julia Grant with a check for $200,000—the largest single royalty yet paid. There was more to come. The Memoirs sold 300,000 sets within two years, and total royalties amounted to $450,000. Ironically, following some initial successes, Twain’s publishing venture suffered the same fate as Grant & Ward, and Twain had to undertake an around-the-world lecture tour to pay off his debts.

Thanks to Twain’s subscription campaign, the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant became, next to the Bible and Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the most visible volumes in 19th-century American homes—at least those outside the South. By 1962, like Uncle Tom, they were rarely read, other than by Civil War buffs, noted Edmund Wilson in his study of Civil War literature, Patriotic Gore. Yet Wilson agreed with Twain’s assessment of them as the best of their kind since Julius Caesar’s Commentaries. “The reader,” Wilson wrote, “finds himself involved—he is actually on edge to know how the Civil War is coming out.”

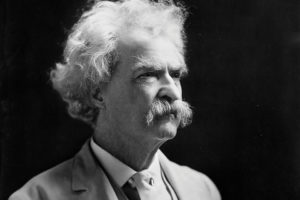

Grant’s race against death to complete his memoirs is often regarded as his most heroic victory, and the book that resulted was generally received as a classic in its field. Matthew Arnold, the English poet and critic, awarded it “the high merit of saying clearly in the fewest possible words what had to be said, and saying it, frequently, with shrewd and unexpected terseness of expression.” If Arnold found fault with Grant’s English, which he described as “without charm and high breeding,” he was answered by no less an authority than Mark Twain. “In their line, there is no higher literature than those modest, simple memoirs,” Twain remarked in a dinner speech in Hartford, Connecticut. “Their style is at least flawless, and no man can improve upon it; and great books are weighed and measured by their style and matter, not by the trimmings and shadings of their grammar.”

Twain was infuriated by rumors, possibly planted by a vengeful Badeau, that Twain had ghostwritten the memoirs; he insisted that his role had been confined to the editorial work normally exercised by any publisher.

“If anyone had suggested the idea of my becoming an author, as they frequently did I was not sure whether they were making sport of me or not,” Grant had scrawled to his doctor at Mount McGregor. “I have now written a book which is in the hands of the manufacturers.” MHQ

JOHN VACHA is the author of four books on the history of regional theater and the coauthor of “Behind Bayonets”: The Civil War in Northern Ohio.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Sword and the Pen

![]()