At about 2 on a foggy morning in 1862, a steamer transporting the 67th Ohio Infantry on the Chesapeake Bay struck another vessel, sending several soldiers, a horse named Big Frank, and two other mounts splashing into the inky-black water. The accident apparently wasn’t serious, and the men were rescued, but no one aboard the steamer noticed that the steeds were missing. Roughly six hours later, about 15 miles from where the collision occurred, a lookout spotted an animated form in the wake of the ship. It was Big Frank, paddling to catch the vessel with his master, 67th Ohio Lt. Col. Henry Commager, aboard.

Like Commager, “a man of immense stature,” Big Frank was large, with flanks as big as a plow horse’s, and had a fearsome personality. Months after his rescue in the bay, the gray charger dashed under fire into a sandy ditch near Fort Wagner (S.C.) during a night assault—the only horse to make it that far. “I do not know that he feared God,” recalled Commager’s son, also a Union officer, “but he was like his rider in one thing, he didn’t fear the devil nor gunpowder….”

No wonder Henry Commager wept when Big Frank, a veteran of several major battles, died from exhaustion in 1864.

Ah, but this was far from the only story of deep appreciation—dare we say love?—that a Civil War soldier had for a horse. At least one veteran gave his wartime mount a military funeral…in his backyard. Another old warhorse—named after the wife of a Confederate guerrilla—earned a national reputation and his master’s undying devotion. A famous general’s revered mount was a leading attraction in postwar parades, and later poisoned and buried, then exhumed and decapitated.

Sometimes love can be complicated. Weird, too.

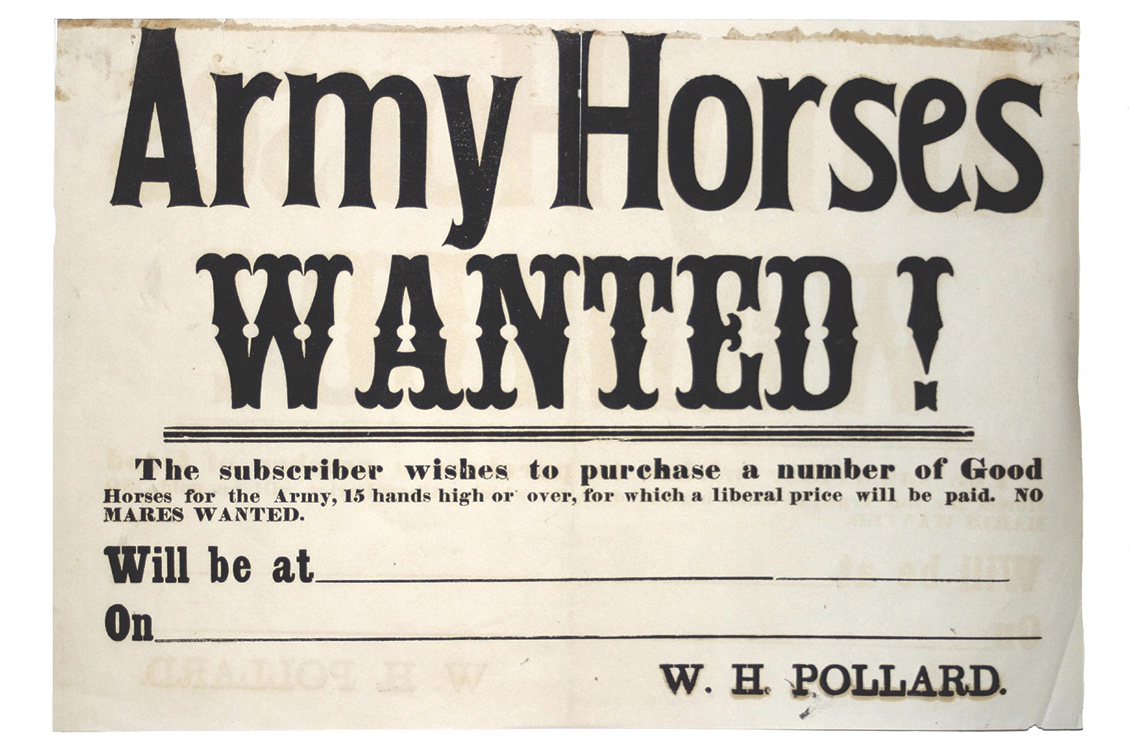

By one estimation, 5.9 million horses—4.2 million for the U.S. and 1.7 million for the Confederacy—were used by the armies. They moved artillery and other equipment, carried soldiers into battle, and helped deliver messages, among many other duties. They suffered, too. Hundreds of thousands died. Horses of generals became famous, inspiring poetry and at least one novel in which the tale was told through the animal’s eyes.

At the Battle of Thompson’s Station (Tenn.) on March 5, 1863, Confederate Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s favorite horse, Roderick, was wounded three times before he was guided to safety by the general’s son. Apparently eager to return to the “Wizard of the Saddle,” however, Roderick leaped over several fences, suffering another wound in the process. As Roderick’s life ebbed away, bad-ass Forrest—who had many other mounts shot out from under him—supposedly wept beside the animal. Roderick was buried on the battlefield.

Roderick’s remains may rest somewhere in an upscale development named after the horse, which could lead to some weird conversations: “Honey, the workers were digging in our flower garden, and they found this huge skull.” A statue honors the chestnut gelding there, too.

In 1956, the Nashville Banner devoted an entire page to The General’s Mount, a poem that recounted Roderick’s demise. Many of the newspaper’s readers probably winced at stanzas such as this:

From mouths and nostrils

Sponged his wounds

Applied a stinging ointment

They washed his knees

And hocks

And pasterns

It’s Roderick! The General’s mount!

Bring the water bucket to him.

Robert E. Lee may not have shed a tear over Traveller, perhaps the most famous Civil War horse of all, but he was enamored with the gray American Saddlebred. In a postwar letter dictated to his daughter to an artist who wanted to depict the horse, he said:

“If I was an artist like you, I would draw a true picture of Traveller—representing his fine proportions, muscular figure, deep chest, short back, strong haunches, flat legs, small head, broad forehead, delicate ears, quick eye, small feet, and black mane and tail. Such a picture would inspire a poet, whose genius could then depict his worth…”

In Traveller, Richard Adams’ 1988 novel, the horse is the lead character, telling stories of wartime exploits while he and Lee enjoyed retirement. The tale was not universally acclaimed. “If there was good information here,” a critic wrote on Amazon.com, “it was lost behind the concept of a horse talking and in dialect, too.”

Less famous than Traveller or Roderick was Almond Eye, the favorite horse of Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. The colorful, often controversial commander was nicknamed “Beast” for his alleged harsh treatment of civilians as military governor of New Orleans during the Federals’ occupation of the city. Decades after the war, newspapers reported a story that, if true, may explain why Butler appeared so grumpy in Civil War-era images. (The “Beast” didn’t mention Almond Eye by name in his 1,000-plus page autobiography.)

While he commanded the Army of the James in front of Petersburg in 1864, Butler heard his prized mount had died from a fall into a ravine. Saddened, he decided to have Almond Eye stuffed. He ordered an Irishman to skin him. According to postwar accounts, the conversation went something like this:

“What! Is Almond Eye dead?” asked the Irishman.

“What is that to you? Do as I bid you and ask no questions.”

The man returned about an hour or two later.

“Well, Pat, where have you been all this time?”

“Skinning the horse, yer honor.”

“Does it take near two hours to perform such an operation?”

“No, yer honor; but thin ye see it took ‘bout half an hour to catch him.”

“Catch him! Fire and furies, was he alive?”

“Yes, yer honor; and ye know I couldn’t skin him alive.”

“Skin him alive! Did you kill him?”

“To be sure I did! You know I always must obey orders without asking any questions.”

Evidently, neither beast was pleased.

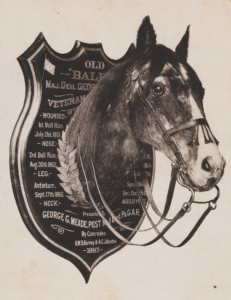

A year after his favorite horse was wounded at Gettysburg, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade was cheered by the mount’s recovery. “I am glad to hear the good news about Baldy,” the general wrote, “as I am very much attached to the old brute.” The animal took a beating during the war, perhaps suffering as many as a dozen wounds. In 1864, fearing the enfeebled, battle-scarred horse would be an “embarrassment” on future campaigns, Meade sent Old Baldy home to Pennsylvania.

After the war, the horse—beloved by veterans, too—marched in parades and in the November 1872 funeral procession for his owner through Philadelphia. Before his death, Meade gave the charger to a blacksmith named John Davis. The general’s conditions: Never sell Old Baldy into servitude, and when his quality of life deteriorated significantly, put him out of his misery humanely. Old Baldy, believed to be about 30, was dispatched on December 16, 1882, with two ounces of cyanide of potash and a pint of vinegar poured down his throat.

“Not a word was spoken,” wrote a local reporter who witnessed Old Baldy’s demise. “True, it was only a dumb animal that was about to stagger, fall and die beneath the deadly action of the potent drug. Yet the mind would conjure up a widely different scene in which Baldy, gay in the trappings of war, with proudly arched neck, heaving flanks and panting nostrils bore amid the clashing of sabers and the hot fire of musketry, the Hero of Gettysburg—Pennsylvania’s noblest son!”

Then things with this famed horse got, ah, a little squirrely.

With Davis’ blessing, two veterans in the Meade Grand Army of the Republic Post No. 1 exhumed the horse’s remains around Christmas Day 1882 on the blacksmith’s farm, cutting off his head. The nag’s noggin was “very tastefully” mounted on a large plaque, with each war wound site noted, and displayed at the post. Old Baldy’s front hooves were made into inkstands.

Perhaps the Pennsylvania owner of another Civil War horse took notes. After a battle against Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early in 1864, Benjamin Franklin Crawford of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry acquired a captured coal black charger. He named the horse Ned.

After the war, Crawford took the mount to his home near Erie, Pa., using him for farming. Old Ned, whose coat eventually turned a solid gray, became a fixture in parades and veterans’ events. The horse “pranced like a colt” when he heard martial music, “which had a wonderful rejuvenating effect on him.” On Decoration Days, children reportedly enjoyed putting flowers on Old Ned more than they did on soldiers’ graves.

In Old Ned’s old age, Crawford fed the horse—“always the boss in pasture,” according to his owner—a diet of bran and apples. “He was cared for as carefully as a child would be,” the veteran’s cousin recalled. After Old Ned died in 1898, at about age 43, his skeleton was donated to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But Crawford kept the hide, which he planned to have tanned.

By late 1864, Dixie Bill was considered jinxed. The horse’s dark history in battle explains why.

At the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (Mo.) on August 10, 1861, the Confederate rider on the dark bay—whose Rebel name was unknown to Federals—was killed by an Iowa soldier. The horse was shot in the neck—the first of four battle wounds the hearty animal suffered during the war.

After Wilson’s Creek, the horse was sent with other captured Confederate mounts to Muscatine, Iowa, where Colonel Sylvester G. Hill led the recently formed 35th Iowa Infantry. Hill purchased the battle-scarred steed, dubbing him “Dixie Bill,” and the horse quickly became a favorite of his staff. Hill rode Dixie Bill throughout the Deep South—at the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and during the 1864 Red River Campaign battles in Louisiana at Pleasant Hill and Yellow Bayou, where his 18-year-old son was killed. While the heartbroken father recovered from a bullet wound during a furlough in Iowa, Major Abraham John of the 35th Iowa was mortally wounded riding Dixie Bill in a skirmish at Old River Lake, Ark., on June 6, 1864.

Six months later, at the Battle of Nashville on December 15, 1864, Hill was killed astride Dixie Bill during an assault on Redoubt No. 3. Afterward, the bay was purchased by a 33rd Missouri Infantry (Union) adjutant, but when he learned of Dixie Bill’s bad battlefield karma, the horse was offered for sale. “With this record, three riders killed in action, he became hoodoo,” an Iowa newspaper reported years later, “and no staff officer could be found who would ride him.”

And so William Bagley, who rose from private to 35th Iowa chaplain, acquired the outcast. When he returned to Iowa near the end of the war, Bagley offered Dixie Bill to Hill’s widow. Thanks, but no thanks, she told him. Perhaps it was too painful to keep a reminder of a war that had cost her family so much.

The Rev. Bagley eagerly took in Dixie Bill at his farm in Tipton, Iowa—a decision he never regretted. In parades throughout the state, the horse often was a star attraction. At veterans’ events, Bagley enjoyed talking about Dixie Bill’s wartime exploits. The bay’s saddle—the one on which Colonel Hill sat during his final ride—became an attraction, too. It was donated by his widow to a local Grand Army of the Republic post.

Even as late as 1878, Dixie Bill—purportedly 29 years old at the time—remained feisty. Before a July 4 parade, “[t]he old horse broke away from Mr. Bagley while in [Wilton],” an Iowa newspaper reported, “and pranced through the streets like a colt, and to judge from his appearance would be good for another campaign.”

When Dixie Bill died on October 15, 1881, he received a grand military funeral. Covered with an American flag, the bullet-scarred charger was laid to rest by Bagley in the backyard of his house on 11th Street in Des Moines. A U.S. flag flew near Dixie Bill’s grave. Scores of veterans attended the service, and area residents talked about the funeral for years.

“[G]reater sorrow could not have been felt from a human being than was felt by a number of people over the death of the faithful old steed,” a Muscatine newspaper wrote.

Dixie Bill’s funeral story was picked up by newspapers throughout the country: “Venerable war-horses who did valuable service during the Rebellion are as plentiful as George Washington’s body servants,” read an account in the Oakland Tribune, “but there is no occasion for cavilling over the remains of ‘Dixie Bill,’ which were consigned to their final resting place in Des Moines with military honors in the presence of many mourners.” At an 1898 reunion of the 35th Iowa, Bagley said a larger crowd attended Dixie Bill’s graveside service than would attend the funeral of any veteran in the room.

Like his horse, the reverend remained vigorous in his old age. “He is still fighting Satan,” a Muscatine newspaper wrote in 1906 about the 86-year-old veteran, “as hard as he fought the rebels.” Bagley died nearly three years later after a brief illness. An obituary highlighted his Civil War service and listed survivors. Dixie Bill was mentioned prominently, too.

“One of [Bagley’s] dearest possessions,” the obituary noted, “was a horse.”

Dixie Bill wasn’t the only horse whose master mustered a military funeral for his beloved animal.

In 1886, 7th Minnesota Infantry veteran William R. Marshall, a former Minnesota governor, mourned the death of Don, his devoted companion of nearly a quarter-century. In Roseville (Minn.) Cemetery, you can see the 29-year-old horse’s gravestone: “Don, My Faithful War Horse,” reads the inscription on it. The horse was also buried cloaked in an American flag.

And, in 1895, Belle Mosby, among several nags billed as the last surviving Civil War horse, was laid to rest in Library, Pa., near Pittsburgh, also with military honors. What a life she led.

Shortly after going into camp in Virginia one evening, 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry soldiers were stirred by a commotion. On the other side of a creek, they spotted an escaped slave, “evidently frightened to death,” astride a beautiful black thoroughbred. Swiped from a Confederate camp by the man, as it turned out.

The banks of the creek were steep, so the soldiers debated how to get horse and rider across to their side. A plank was placed across abutments of a ruined bridge, allowing the “snorting and trembling” horse to walk to the other side. When the pair finally made it, soldiers cheered.

A Union cavalryman named the horse “Belle Mosby” because the “beautiful creature reminded him to some extent” of the “beautiful gypsylike wife of Guer[r]illa [John S.] Mosby…” There is no known record of what Pauline Mosby thought about the comparison.

In exchange for an overcoat, a lieutenant in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry acquired the bullet-scarred horse from the escaped slave. In a fight against Rebels the next day, the officer rode the animal after two other mounts were shot out from under him.

“She seemed to bear a charmed life, darting and flashing around through the scrap like a charmed creature,” recalled Joseph R. Phillips, a farrier in the Pennsylvania regiment. The horse was hit several times by stray bullets—“only flesh wounds,” the farrier said. A day or two later, the lieutenant gave the “hard as nails” horse to Phillips, his friend. An examination of Belle Mosby’s teeth in 1865 determined she was five years old.

After the war, Phillips worked Belle Mosby regularly at his farm in western Pennsylvania until she was wracked with rheumatism in the early 1890s. By then, Belle Mosby had earned national fame—nearly every member of the Grand Army of the Republic had heard of her, according to a newspaper account. At the national G.A.R. encampment in Pittsburgh in 1894, thousands of pictures of Belle Mosby were sold. But the next year, a bitter cold snap evidently led to the horse’s demise. In an orchard at Phillips’ homestead, Belle Mosby—age about 35—was buried with military honors, wrapped in flags.

“Comrade Joe Phillips,” a Pittsburgh newspaper reported, “…wept like a child.”