Union cavalry’s fate hung on the health of its four-legged warriors

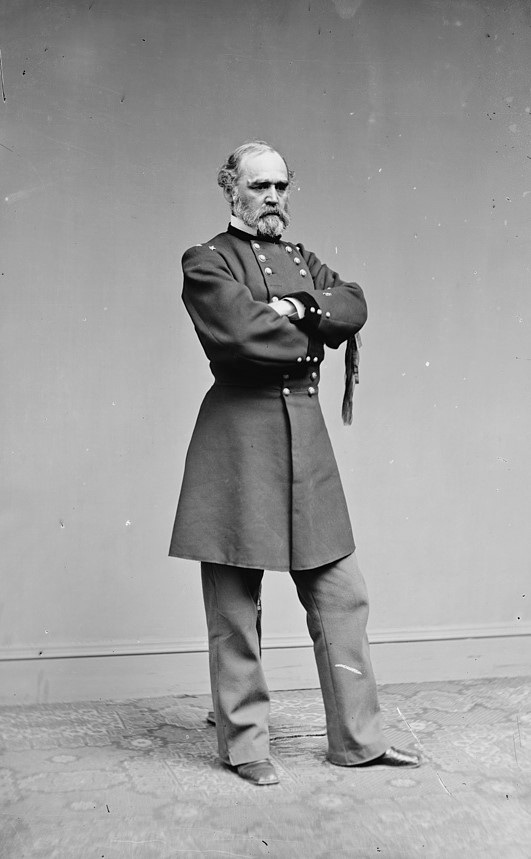

Brigadier General Montgomery Meigs, quartermaster general of the Union Army, walked into his office in Washington, D.C., every day never knowing what new challenges awaited him. The two main theaters of the war dominated his daily workload, but on any given day Meigs responded to dozens of requests from every corner of the country asking for matériel: barracks and hospitals, clothing, coal, construction lumber, firewood, laborers, railcars, shipping, wagons, and ambulances. Over the course of the war, Meigs disbursed $2 billion (nearly $70 billion today), supplying the needs of the soldiers. He felt keenly the responsibility to spend the nation’s money wisely and waged a constant war within the war against fraud and corruption.

Arguably, however, none of his daily trials surpassed the challenge of supplying the thousands of horses and mules required by the ever-expanding army. By January 1863, little could have surprised Meigs, until, on January 15, he read a request for 8,000 horses from Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, commanding the Army of the Cumberland. Wintering in Tennessee after his battle at Stones River, Rosecrans had decided to expand his cavalry force by mounting 8,000 of his infantrymen. The request must have staggered Meigs. “It will take some time to get 8000 horses unless you can seize them in the field,” Meigs replied.

More than anyone, Meigs understood the big picture, as he provided matériel to every army and outpost in the country. He could not foresee the course of future events, but he appreciated how events and demands for supplies in one theater of the war affected his ability to provide similar items to other areas of the country or to other armies. Thus, Meigs knew the degree to which “Old Rosy’s” request would affect the supply of horses nationally. He may not have realized, however, that he would still be struggling to meet the general’s request five months later or the extent to which the request continued to affect his ability to acquire and deliver horses to the Army of the Potomac in May and June, during the Chancellorsville campaign and the beginning of Robert E. Lee’s drive into Pennsylvania.

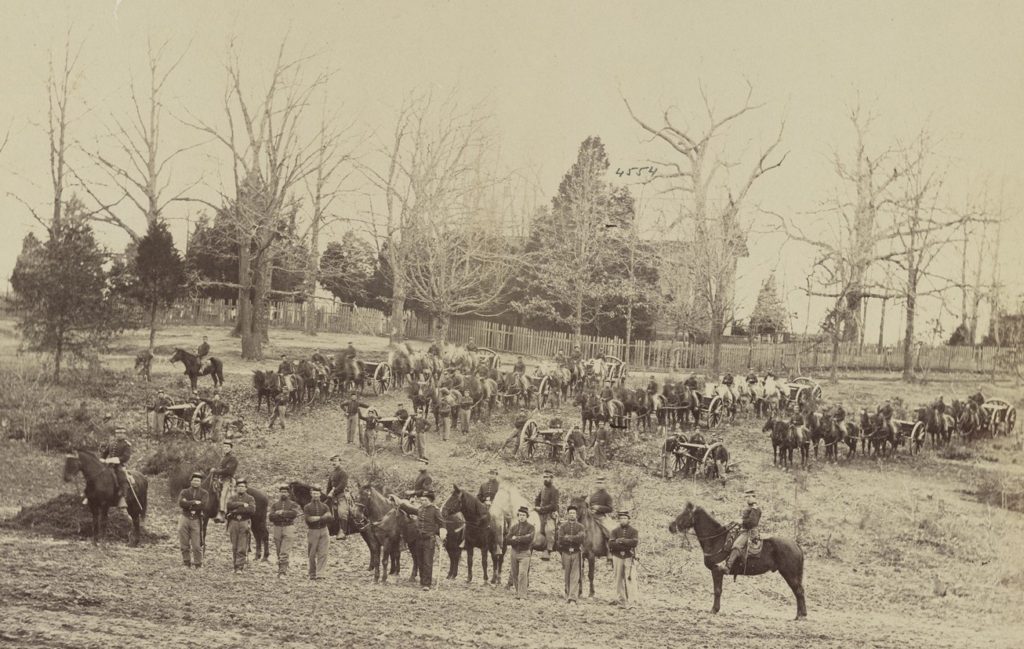

In April 1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, commanding the Army of the Potomac, devised what seemed to be a brilliant plant to break the stalemate along the Rappahannock River and defeat Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. In February, Hooker had, at President Abraham Lincoln’s suggestion, organized his cavalry into a separate entity, the Cavalry Corps, and, at Lincoln’s suggestion, Hooker had designated Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to command the corps.

Over the next few months, Meigs supplied Stoneman with thousands of fresh horses, as the cavalryman prepared his command to conduct a raid against Lee’s supply lines as a key part of Hooker’s ambitious plan. When Stoneman finally set out in mid-April toward Richmond, Va., he encountered incessant storms, flooded rivers, and roads swimming in mud. Returning nearly a month later, his men and animals exhausted, Stoneman immediately came under fire from Hooker for what the army commander deemed an underwhelming effort. As a means of assessing the raid, participants counted, among other things, the number of horses captured from the enemy and the condition of their own animals upon their return. Colonel Judson Kilpatrick tallied “over 400 splendid horses,” seized on his march from Richmond to Yorktown, while Stoneman’s main force supposedly seized “1000 or 1500 horses [and] 500 mules.” Major General Daniel Butterfield, Hooker’s chief of staff, confidently told Meigs that Stoneman’s troopers had “captured a sufficient number of horses to remount all that gave out or were broken down en route, and only complain of their horses being leg-weary and wanting shoes on their return.”

Suspicious of such reports, Hooker on May 12 demanded to know the number of Stoneman’s men ready “for immediate duty in the field.” After a hasty appraisal of the 12,000 animals with the command at the outset of the raid, Stoneman now counted just “2,000 horses” available, “provided but little marching is required.” Nearly 1,000 animals had been abandoned on the march, most of the horses seized were unsuitable for cavalry service and the captured mules needed immediate rest and rehabilitation. One brigade counted a mere 346 men and horses available for duty. The early returns had either been hopelessly optimistic or intentionally deceptive.

The Cavalry Corps needed to be remounted, but in a tight market the cost would be exorbitant. In early May, prior to Stoneman’s return, horses averaged about $125 per head but the price rose with demand; by the end of the month the average price had increased 20%. As Meigs explained to a subordinate on May 25, Rosecrans’s earlier request for 8,000 horses continued to affect both market price and availability. “The enormous demand from Gen. Rosecrans, a sudden demand for 4000 horses for Western Virginia, and for 5 or 6,000 for the army in Eastern Virginia…[has] affected the market, and prices are inflated, but still the supply here is short. It is hoped that this increase in price will bring out the stock and that prices will fall again soon.” Instead, the demands of the coming campaign drove prices ever higher.

Seeking to placate Hooker, Meigs explained on May 28, “I am using every exertion to procure [horses] and after a check due to a sudden increase in prices and the large demand for Gen. Rosecrans…they are beginning to come in rapidly.” Horses arrived a few hundred at a time, however, and Meigs needed 10,000 just to meet his current needs in the East, to say nothing of orders from other commands scattered around the country, including Rosecrans’. Meanwhile, escalating conflicts with Native Americans led to the formation of several new mounted regiments.

The quartermaster general tallied the incoming requisitions even as he read the newspaper accounts of Stoneman’s raid and he grew increasingly suspicious. The “cavalry, notwithstanding the fine statements of our own special correspondents, is in a sad state,” Meigs told a subordinate. “They call for six thousand horses. Compare this with newspaper accounts. Gen. Hooker is as much disappointed as [I am] at this.” Kilpatrick, on the Virginia Peninsula, also needed horses but Meigs, who had read the young cavalry colonel’s boasts in the papers, refused to send any until the more “urgent requisitions now on file can be filled.”

With the furor over the cost and value of the raid mounting, Hooker replaced the ailing Stoneman with Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton on the same day a Union spy walked into Maj. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman’s office in Washington and warned of a planned Southern cavalry raid against the city. The spy had just left Richmond where he had seen Union uniforms being prepared to disguise the raiders, who intended to enter the capital to kidnap Lincoln and members of his cabinet. No evidence has been found in surviving Southern records confirming the spy’s report, but Northern officials could not ignore the possibility and risk Lincoln’s life. The notion of a raid soon dominated the minds of military officials in Washington, as well as in Hooker’s army, who saw every shred of intelligence regarding Lee’s cavalry, then gathering in Culpeper County, Va., as further proof of the alleged raid. As Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck told Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton just three days after the spy made his report, “It is rumored that Stuart and Lee are collecting a cavalry force at Culpeper…probably for a cavalry raid.”

The timing could not have been worse for Pleasonton’s rebuilding efforts. The task of preventing Southern raiders from entering Washington fell to Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel, commanding the cavalry division assigned to the Defenses of Washington. Thus, for the next several weeks Stahel, rather than Pleasonton, received the lion’s share of the remounts coming into the Washington depots. Pleasonton’s men also relieved Stahel’s troopers of picket duty, allowing Stahel, rather than Pleasonton, to rest and refit his command. On May 24, Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls, Hooker’s quartermaster, asked Meigs for 2,500 remounts, reminding him, the need for “cavalry horses with this army has never been so severely felt as at this moment,” but Meigs had no horses to spare. “I have just furnished Gen. Stahel’s command with 1,000 [horses],” one of Meigs’s subordinates told Ingalls the next day, “and…have exhausted the supply of horses [in Washington] and Alexandria, having taken all serviceable horses from the wagon masters, teams [etc.]”

On May 27 Pleasonton reported his effective strength at less than 4,700 men. Hooker fumed, complaining to Stanton, “I would pitch into [Stuart] in his camps…if General Stahel’s cavalry were with me for a few days.” Hooker viewed Stahel’s remounted division as an immediate means of rebuilding his Cavalry Corps; he made the statement as a ploy to have Stahel’s division transferred to the Cavalry Corps, rather than as a reflection of his willingness to share any future battlefield glory. The scheme failed, and when Pleasonton finally did “pitch into Stuart” on June 9 at Brandy Station, he did so at a numerical disadvantage. Stahel had moved into position to aid Pleasonton, but Hooker sent two infantry brigades to bolster Pleasonton’s strength rather than call upon Stahel for assistance.

On the eve of the great clash at Brandy Station, Ingalls asked his subordinates to cull horses “suitable for cavalry” from their teams, explaining, “Cavalry horses are scarce, and in great demand.” On the same day, Meigs told Brig. Gen Daniel Rucker, commanding the Washington Depot, “General Stahel…still needs…1,500 horses.” When Pleasonton surrendered the battlefield on the evening of June 9, he left an unknown number of dead and wounded horses on the field. Many others carried their riders off the field only to fall victim to wounds or other injuries over the coming days. Two regiments, the 5th and 6th U.S. Cavalry, lost more than 100 horses between them. If their loss is any kind of an accurate measuring stick, then Pleasonton might have lost 1,000 cavalry horses, to say nothing of artillery horses.

The day-long clash at Brandy Station bolstered the confidence of Pleasonton’s troopers. They began to believe they could now stand against Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s horsemen on any field. On June 10, Lee’s army resumed its march, heading toward the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Shenandoah Valley. As Lee’s infantry began the long trek toward Maryland and Pennsylvania, Stuart moved his cavalry into the Loudoun Valley of Northern Virginia. His efforts to screen the infantry resulted in a series of cavalry clashes along the Ashby’s Gap and Snickersville Turnpikes at Aldie, Middleburg and Upperville a week later.

On June 20, the day before the grueling all-day battle of Upperville, Ingalls asked to have horses at the Washington Depot “shod and ready for instant issue and service. The losses by scouting and in battle are huge.” At the same time, Meigs told a subordinate purchasing horses in Indianapolis, “Destruction of horses here by hard service is great.” During the nine-hour battle the next day, Pleasonton, aided for part of the day by a brigade of infantry, drove Stuart ten miles into Ashby’s Gap. Reaching the base of the mountains, the Federals found their way blocked by Southern infantry and artillery. Only one small Union patrol reached the crest and observed part of Lee’s great army below.

Determining accurate numbers for horses lost in a given battle is difficult at best, but when Hooker abandoned his lines around Falmouth on June 13, Capt. Samuel McKee headed north with about 1,000 men who either needed horses or who rode animals needing to be shod. McKee’s caravan included men still waiting to be remounted following the Stoneman Raid and others who lost their mounts at Brandy Station. Another 350 dismounted men reached Alexandria on June 14. They would also have been men who lost their horses at Brandy Station or as a result thereof. Stuart’s rumored raid continued to affect Pleasonton’s strength, however, as Stahel, rather than Pleasonton, received 700 horses on June 15. Taken together, these figures represent nearly a division of men who might have given Pleasonton the strength he needed to push Stuart through Ashby’s Gap before Southern infantry arrived to plug the breech on June 21. As a New York Times reporter noted the same day, “fully half of some of our horse regiments are now ineffective for want of horses.

By June 22 Pleasonton’s need for horses had become especially acute, and thousands of his animals needed to be reshod before they went lame. The turnpikes, surfaced with layers of stone, tore off or wore out horseshoes at an alarming rate, as General Stuart mentioned in his campaign report. Speaking of the fighting at Middleburg on June 19, Stuart explained, the Union attack “was met…by…two brigades, which rough roads had already decimated for want of adequate shoeing facilities.” Concluding his long report, Stuart returned to the effect of the roads in the Loudoun Valley on his horses, stating, “the rough character of the roads and lack of facilities for shoeing added to the casualties of every day’s battle…in this way some regiments were reduced to less than 100 men.” Pleasonton concurred, telling Hooker, “the turnpike cripples up our horses when they are unshod,” but while Stuart had to disperse his men to local blacksmith shops, Pleasonton had other options. On June 19, he ordered ten portable forges, along with blacksmiths and 10,000 shoes sent out from Washington, though only six forges arrived. He split these evenly between the two divisions, but with thousands of his men stuck on picket lines or escorting supply trains against attacks from Maj. John Mosby and his partisans, the number of animals reshod in Pleasonton’s command is impossible to assess.

Beyond the concern of his animals going lame, Pleasonton had lost nearly 1,000 men killed, wounded, or captured at Aldie, Middleburg and Upperville. Horse casualties are impossible to determine but hundreds had been captured by Stuart’s cavaliers, in addition to those killed or wounded. Three cavalry regiments, the 1st Massachusetts, 1st Rhode Island and 4th New York, nearly a brigade of men, had been rendered combat ineffective. Of the three regiments, only the 1st Massachusetts followed the army into Pennsylvania, but it remained out of action at Gettysburg as a headquarters escort for the Sixth Corps. All three regiments had been Kilpatrick’s brigade in the Loudoun Valley, the only brigade to participate in all three battles. The other two regiments, the 2nd New York and 6th Ohio, had also been decimated in the fighting. By the end of the battle at Upperville, the Ohio companies may have averaged but ten men or, more accurately, ten horses per company. Though they crossed the Potomac, these two regiments remained in Maryland, guarding the Union supply base at Westminster.

Horses lost on the battlefield, either to death or capture, meant lost equipment, including saddles, saddlebags, blankets, bridles and halters, bits, brushes, curry combs, picket pins, feedbags and spare ammunition, as well as the rider’s personal items and spare clothing. When a horse crashed to the ground from a bullet, collision or shell wound, the impact could easily damage or destroy the trooper’s carbine, which he carried on a sling across his shoulder. The man’s saber might also be lost or damaged by the impact.

Contrary to persistent myths about Federal depots and arsenals overflowing with the best equipment and the latest weapons, many of the facilities had been emptied by late June, as militia units raised for the emergency in Pennsylvania requisitioned the same equipment and weapons required by Pleasonton. An entire regiment had missed the fight at Brandy Station for want of 727 saddles which did not reach the men until June 18. Hinting at horse casualties within his command, a division commander requested another 600 saddles two days after the fight at Brandy Station. When they arrived, many proved defective. As Pleasonton told Meigs on June 26, “The saddles of the McClellan pattern furnished from Troy N.Y. are unfit for use. They ruin the backs of the horses. Please have saddles from other makers supplied, as it will save us many horses.

The most enduring myth concerns Brig. Gen. John Buford’s men and the famed Spencer carbines which allowed mere cavalrymen to hold Lee’s vaunted infantry at bay on July 1. The truth is vastly different, as army officials did not sign the first contract for the carbine until mid-July and the first weapons did not reach the army until October. Only two regiments in Brig. Gen. George Custer’s Michigan Brigade carried the Spencer rifle at Gettysburg.

Rather than carrying repeating weapons, the cavalry struggled to receive any weapons to replace those lost in battle. When a regimental commander called for new carbines to replace those lost at Brandy Station, he received 16 crates of repaired weapons instead. When Buford called for Sharps carbines after the battle, he received “the best on hand,” including 50 French rifles. When Pleasonton asked for Sharps carbines, he received the less popular Burnside model. By June 19, only 500 Burnside carbines remained in the Washington Arsenal. Three days later the arsenal had no carbines to distribute, and “I cannot tell when there will be any,” the officer in charge told a subordinate. And, with no new saddles on hand, the officer resorted to repairing old equipment or forwarding unrepaired “saddles, bridles & halters.”

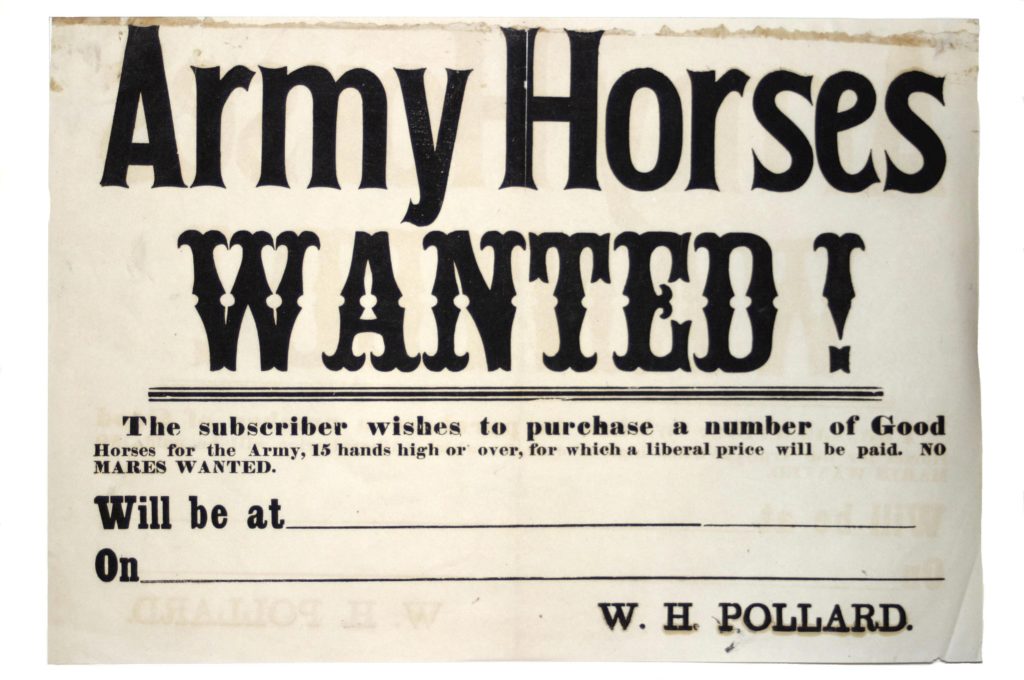

Remounted men began returning to the army as horses reached Washington and Alexandria, 25 men in one detachment, 125 men in another. On June 27 more than 500 left Washington but nearly 1,000 men remained in one depot two days later. As soon as the men returned, however, other problems became apparent; many of the newly issued horses were too young to withstand the rigors of cavalry service. When advertising for horses, the military clearly stated what animals would be accepted in terms of age, sex, size, and color; honest quartermasters did not accept mares or horses younger than six years of age. Then, on June 1, Meigs relaxed the prohibition on animals under six years old. “I am [aware],” he explained, “that a five year old horse is not as fit for cavalry service as one six years old, but it is a choice between five years old and a deficient supply.” These young animals saw their first combat at Aldie on June 17 and many “gave out,” as Pleasonton later complained. “I shall have many more dismounted men in a short time, from the hard service required of the horses and their unfitness to stand it,” he told Hooker.

As demand and prices skyrocketed and pressure to obtain large quantities of animals grew, some quartermasters gave in to unscrupulous contractors. Many of the men in the purchasing chain had no cavalry background and thus no understanding of the demands of mounted service. Farmers and contractors forced them to accept mares or lose an entire lot of animals. Others tried to slip all manner of old, sick, or otherwise unacceptable horses past beleaguered inspectors. On June 21, officers in Washington accepted only 19 of 300 animals in one lot. In Michigan, an inspector rejected 211 of 315 horses for a variety of reasons, including those blind in one or both eyes and others with breathing problems.

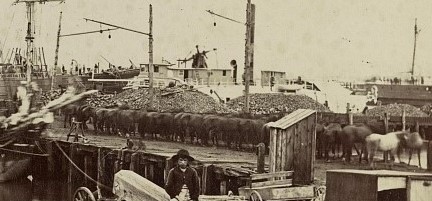

The animals reached Washington from cities such as Chicago, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Syracuse, and Boston. They had been cooped up in unventilated boxcars for days, and though regulations prescribed adequate food, water, and exercise every 8 to 12 hours, these rules often proved impracticable or were simply ignored. The animals reached Washington stressed, aggressive and hungry. Quickly herded into large corrals, they often “lashed out, kicking and biting at neighbors, inflicting cuts and broken bones, and giving every indication of their distress.” Most arrived unbroken. Without any chance to rest or recover weight lost on their journey, the animals quickly made another trip out to the army, where they soon found themselves on a picket rope alongside other horses intent on maintaining their dominance. Soldiers who received them had no idea what they might expect when they rode into battle for the first time and their new mount experienced the terrors of combat. As one historian explained, “For a herd animal, with a strong preference for close social relationships, the camps, and corrals…may not only have been profoundly frightening places, they may…have been very lonely ones too.”

Trying to determine the effectiveness of the remount system or the actual strength for any given regiment on a given day at Gettysburg or in a particular engagement, such as East Cavalry Field, is impossible. Every company sergeant or officer completed their muster rolls a little differently and some gathered information others did not. The June 30 muster rolls offer the best snapshot of regimental strength at Gettysburg, but the Cavalry Corps had been on the move for days and commands remained scattered. Elements of the corps fought skirmishes or battles on the 30th, immediately altering numbers which may have been gathered at morning roll calls.

Determining the true strength of any one company, regiment, or brigade, meant counting both men and horses, but not every record keeper did so. Still, some rolls are more helpful than others. One company of the 8th New York, which fought with Buford on July 1, had 56 men but only 43 horses, so the company had an effective strength of 43 men. Some of the reporting companies from the 8th Illinois reported similar deficits, while others had a surplus of animals. The 10th New York, which fought at Brinkerhoff’s Ridge on July 2, counted 460 officers and men on June 30, with 303 serviceable horses and 191 unserviceable animals. Thus, the regiment’s effective strength was significantly less than might be assumed at first glance. Only one company from the 3rd Pennsylvania, which fought at East Cavalry Field, counted serviceable horses on the June 30 roll, with just 30 horses for 41 officers and men. The 1st Pennsylvania counted 301 officers and men, but nearly 50 unserviceable horses in an incomplete tally. One company of the 1st U.S., which fought on South Cavalry Field, counted 61 men but only 33 horses, while a company from the 2nd U.S., which fought alongside the 1st, counted 57 men and just 45 horses with 8 unserviceable. Other companies recorded a surplus of horses.

The punishing pace of battle, combined with summer heat and long marches over the first two weeks of July, meant an ever more critical need for fresh horses. For the period of May to July 1863, the Cavalry Corps received, by one accounting, nearly 17,000 remounts at an estimated purchase price of $2.3 million (nearly $80 million today). Feeding, transporting, housing, equipping and other ancillary costs sent the final price higher.

On July 4, Ingalls told Meigs, “The loss of horses in these severe battles has been great in killed, wounded and worn down by excessive work…I think we shall require 2000 cavalry and 1500 artillery horses as soon as possible. Two days later, Ingalls upped the number to 5,000 horses. Meigs immediately ordered trains bringing horses from Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and other locations to make their way directly to Frederick, Md., rather than Washington, D.C., but a shortage of rail cars delayed deliveries. On July 8, Meigs counted “7,000 horses…on their way to the army,” but he remained at the mercy of an under-strength labor force and a shortage of train cars. Day after day, until the army re-crossed the Potomac River, Meigs prodded, cajoled, counseled, and protected his overworked subordinates who toiled to surmount every challenge in providing for the needs of the army.

Meigs had reported on June 1, 1863, that there were more than 14,000 disabled horses in just three depots, including 5,000 in Washington. Estimates for the post-Gettysburg period have not been located, but the grim toll the campaign exacted among the army’s horses and mules sparked the final decision to create the Cavalry Bureau and the massive horse depot at Giesboro Point in the District of Columbia. Veterans believed the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps came of age during the Gettysburg Campaign. Historians generally agree, viewing the clashes at Brandy Station, Upperville and East Cavalry Field as the key crucibles on the long, difficult road to battlefield supremacy. But we should never overlook the animals, especially the more than 1 million horses and mules who died during the war, or the men who provided them.

This story from America’s Civil War was posted on Historynet.com May 19, 2020.