Marked “Personal & Private,” the letter arrived at President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia, in April 1945, addressed to Grace Tully, the president’s secretary. It was written on the black-bordered stationery of a widow mourning her husband. The widow was Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, who had been Roosevelt’s lover nearly 30 years earlier. Now she was writing to arrange a secret rendezvous with her old flame.

She appeared in Warm Springs a few days later and was sitting with Roosevelt when he suffered a fatal stroke.

Rutherfurd quickly fled, and Tully filed the letter among papers she kept as mementos of her White House years. Tully’s trove of 5,000 documents, which includes the personal files of Missy LeHand, her predecessor as FDR’s secretary, were not generally available to scholars or the public until the National Archives obtained them with the help of an act of Congress. The potpourri of memorabilia, notes and correspondence promises to shed new light on many aspects of FDR’s life, but none as poignant as his star-crossed relationship with a lover who remained close to his heart to the end of his days.

FDR and Lucy Mercer Meet

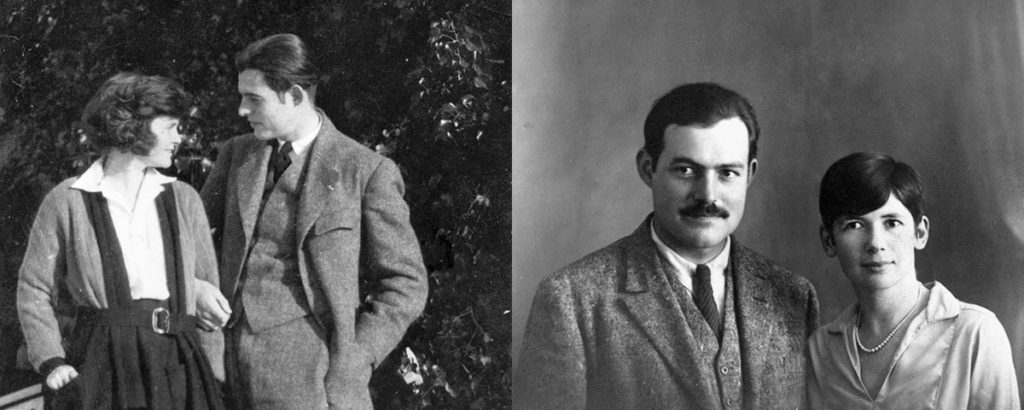

They met in Washington in 1913, when Eleanor Roosevelt hired Lucy Mercer as a part-time social secretary. At the time, FDR was assistant secretary of the Navy, a handsome, athletic 31-year-old man who frequently played 18 holes of golf before work. Lucy was 24, the vivacious daughter of a prominent Maryland family. Eleanor, 29, was a harried mother of three children and pregnant with a fourth. She desperately needed help, and Lucy provided it while charming the children.

“I liked her warm and friendly manner and smile,” Anna, the oldest of the Roosevelt children, recalled later.

“She had the same brand of charm as father,” son Elliott Roosevelt remembered. “And there was a hint of fire in her warm, dark eyes.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

From Friends to Lovers

No one knows when Lucy and Franklin began their affair, but it was in progress by the time Roosevelt sailed to France in 1918 to inspect naval forces fighting the Germans in World War I. When he returned 10 weeks later, he was so sick with pneumonia that sailors had to carry him into his Manhattan townhouse. As he lay in bed, Eleanor unpacked his bags and found a packet of perfumed letters wrapped in a velvet ribbon. They were love letters from Lucy.

“The bottom dropped out of my particular world,” Eleanor later wrote.

Eleanor confronted her husband and told him she was willing to divorce if that’s what he wanted. Perhaps he did, but his mother threatened to disinherit him if he sullied the family name. And his political adviser, Louis Howe, told him divorce would kill any chance of winning high office.

So the marriage of Eleanor and Franklin endured but was forever changed. Even though they remained affectionate partners, they would never again be lovers. And Eleanor extracted a promise: Franklin must never see Lucy Mercer again.

For 20 years, Franklin and Lucy kept their distance. When the affair ended, Lucy took a job as a governess for the six children of a rich widower named Winthrop Rutherfurd, whom she married in 1920. That same year, the Democrats nominated James Cox for president and chose Roosevelt as his running mate. Warren Harding creamed Cox that November, but FDR had become a national political figure, and his future looked promising.

Recommended for you

FDR gets polio

A few months later, in the summer of 1921, FDR was stricken with polio, which nearly killed him and left his legs paralyzed. Eleanor bathed him, shaved him, fed him, brushed his teeth and administered enemas to empty his blocked bowels. For two long years, he struggled to recover use of his legs, but it was futile: The once-vigorous athlete was now a paraplegic.

Somehow, his spirit endured, and he emerged from his ordeal a warmer, more compassionate man. “Anyone who has gone through great suffering,” Eleanor explained, “is bound to have a greater sympathy and understanding of the problems of mankind.”

In 1928, he ran for governor of New York and won. In 1932, he ran for president and took office in the midst of the Great Depression. He launched the New Deal and won reelection in 1936, 1940 and 1944.

Through it all, Eleanor served as his political adviser and roving ambassador, visiting farms, factories, schools and slums, then returning to the White House to report what she’d seen and to urge her husband to do more for the downtrodden. He appreciated her advice, but he sometimes tired of her ceaseless crusading and just wanted to relax with a cocktail and a joke. Eleanor wasn’t good at joking. She seemed incapable, her son Jimmy once said, of giving FDR “that touch of triviality he needed to lighten his burden.”

Rekindling the relationship

For that, he turned to lighter spirits, one of whom was Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd. A new stage in the relationship began sometime in the early 1940s, when Lucy, using the alias “Mrs. Paul Johnson,” would visit the White House to see her old friend. Sometimes she came alone; sometimes she brought her daughter. Once, she came with an artist friend, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, who painted the president’s portrait. These liaisons were almost certainly platonic — other people were usually present — but FDR kept them secret from Eleanor.

“I doubt father felt he was doing anything wrong in seeing Lucy,” Jimmy Roosevelt said, “but he believed mother would take it badly and would be hurt.”

In March 1944, Lucy’s husband died. That summer, Roosevelt asked his daughter Anna if she’d help him arrange his meetings with Lucy. Anna knew the story of her father’s affair but reluctantly agreed to help. Her father was tired and lonely and burdened with the pressures of leading his nation through the bloodiest war in history, and Lucy seemed to lift his spirits.

“They were occasions which I welcomed for my father,” Anna later recalled, “because they were lighthearted and gay, affording a few hours of much needed relaxation.”

When FDR returned from the Yalta conference in the winter of 1945, he was thin and sickly, his skin a ghostly pale. Still, he told Lucy that she could bring Shoumatoff to Warm Springs to paint another portrait. So Lucy wrote her “Private & Personal” letter to Grace Tully to arrange the details. She ended the letter with concern for the president’s health: “I really am terribly worried — as I imagine you all are.”

On Monday, April 9, Lucy and Shoumatoff drove to Warm Springs, where FDR made cocktails and regaled them with stories of Yalta. The next day, looking ashen and haggard, he sat for Shoumatoff. After a nap, he and Lucy drove to a nearby mountaintop to watch the sunset.

FDR’s LAST BREATH

On April 11, FDR worked on the speech he planned to deliver at the opening of the United Nations. That night, his hands shook so much when he tried to pour cocktails that Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau had to hold the glasses.

The next morning, the president dictated a cable to Moscow, signed some bills and posed again for Shoumatoff while chatting with Lucy. He read a State Department memo and laughed, saying, “A typical State Department letter — it says nothing at all.” He seemed happy and everybody agreed that he looked healthier. But suddenly his head slumped forward and one arm jerked spastically. “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head,” he said, and then he collapsed.

His valet and butler carried him into the bedroom. His doctor came quickly and recognized that the president had suffered a severe cerebral hemorrhage. Three hours later, FDR stopped breathing.

“We must pack up and go,” Lucy told Shoumatoff.

Eleanor caught a flight from Washington, D.C., as soon as she heard the news and arrived in Warm Springs around midnight to find the house crowded with stunned staffers and grieving relatives. She asked how the president died, and somebody told her the story: He was sitting for a portrait by Madame Shoumatoff, who had shown up a few days earlier with Lucy Rutherfurd.

Eleanor showed no emotion. She entered the bedroom where her husband’s body lay, and closed the door. When she emerged, she asked more questions and learned that Lucy had frequently visited the White House, and that Anna had made the arrangements. “Mother was so upset about everything,” Anna recalled, “and now so upset with me.”

Anna worried that her mother might never forgive her, but that wasn’t the case. “After two or three days, that was all,” Anna said. “We never spoke about it again.”

Eleanor Roosevelt was far too big-hearted to hold grudges for long. Weeks later, unpacking her husband’s belongings, she found one of the portraits painted by Shoumatoff, and arranged to have it sent to Lucy Rutherfurd.

“Thank you so very much. You must know that it will be treasured always,” Lucy wrote back. “I send you—as I find it impossible not to, my love and deep sympathy.”

Peter Carlson writes our Encounter column. His latest book is K Blows Top.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.