[imagebrowser=55]

Missing for more than half a century, early work of Robert Capa and two colleagues reveals the genesis of modern war photography.

This article is from the Winter 2011 issue of MHQ, which will be available on newsstands Tuesday, November 16th, 2010. Visit the HistoryNet store to order your copy today!

After Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, photojournalist Robert Capa knew he was no longer safe in Europe. A Jewish immigrant from Hungary living in Paris, Capa fled to New York City, leaving in his studio more than 100 rolls of film, including thousands of images from the Spanish Civil War.

That film, lost for more than a half century, has surfaced, offering a new perspective on the war as well as fresh insights into the groundbreaking images that established Capa as one of the world’s best war photographers. Stored in three cardboard boxes, the negatives made their way to Marseilles and into the hands of a Mexican diplomat, General Francisco Aguilar González, who returned home to Mexico City with them. González died in 1967, and the historical value of the film went unnoticed for almost three more decades.

To showcase the discovery, the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York City is hosting an exhibition, “The Mexican Suitcase,” the nickname given the three cardboard boxes. It includes recovered images from two Capa colleagues: his lover and business partner Gerda Taro, and David Seymour, also known as Chim.

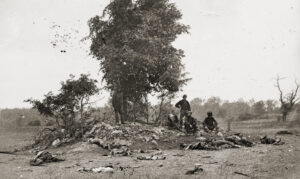

Each in their 20s, the three photographers were crusading leftists who hoped to help anti-Fascists in Spain fighting the Nationalists of General Francisco Franco. They joined Republican soldiers—many of them untrained farmers and workers—on the front lines and documented the resistance of everyday citizens through street scenes, portraits of volunteers, protest photos, images of militia in training, and more.

Taro is believed to have been the first female war photographer. Seymour was acclaimed for photos that document the effects of war on average people. Capa, too, developed his trademark style during the war—the first of many that he would cover. Unlike other photographers, who worked the sidelines of battle or captured its aftermath, he plunged into combat to capture dramatic and often horrific images. “If your pictures aren’t good enough,” he often said, “you’re not close enough.”

While negatives for several famous photographs were found in the boxes, others were notably absent, including those relating to Capa’s The Falling Soldier. That iconic image allegedly captures a Spanish soldier at the moment he’s hit by a fatal bullet; critics charge that Capa staged the photo, though the ICP contends it’s authentic.

All three photographers died in action. Taro was killed in July 1937; during the Republican retreat at the Battle of Brunete near Madrid, she hopped onto the running board of a car that was later sideswiped by a tank. Capa died in 1954 when he stepped on a land mine while on assignment in Indochina. Seymour was killed two years later by machine gun fire while covering the Suez crisis.

“The Mexican Suitcase” is on view through January 9; for details visit icp.org.