The romance of ranching is a myth. The reality of ranching is work. The people who live and work Wyoming’s ranchlands, no matter the location, are a hardy breed. When it is snowing and the wind is blowing—winter conditions common throughout the “Cowboy State”—they simply don a few more layers of clothing before venturing out to tend livestock, forking hay to cattle and seldom begrudging passing deer or elk from also eating a mouthful or two.

Photographs from Ranchland: Wagonhound, by Anouk Masson Krantz, The Images Publishing Group, 2022.

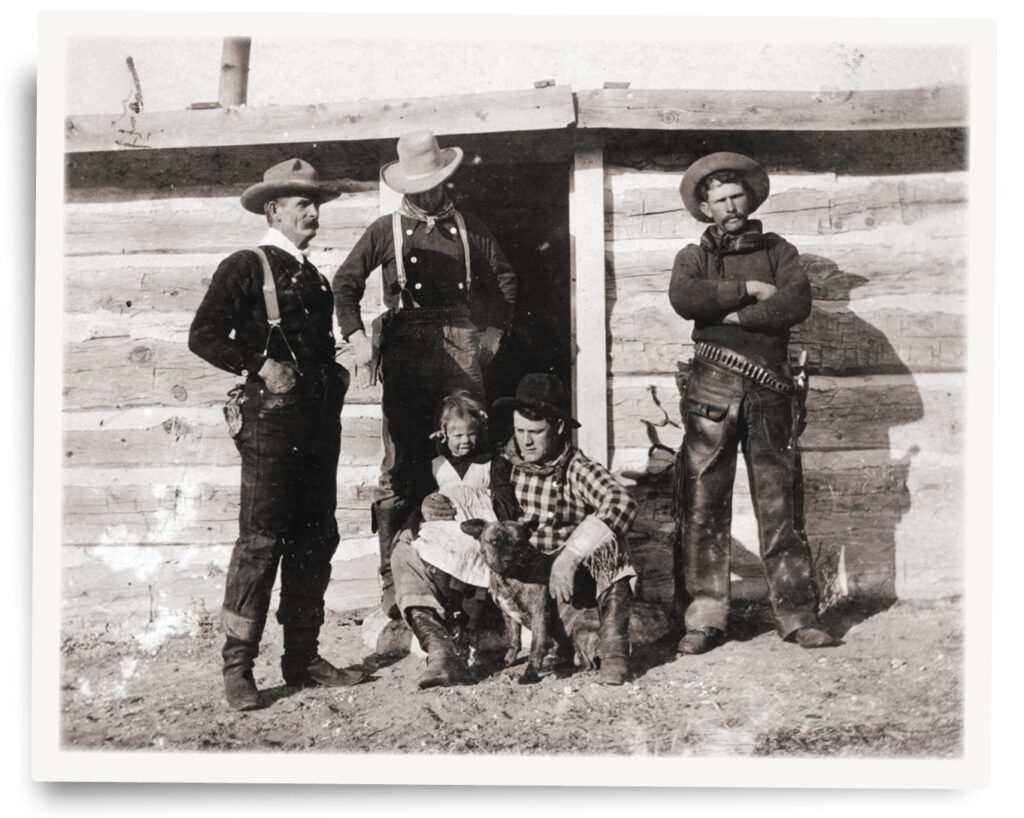

Historical photographs appear alongside Krantz’s images below, showing Wyoming ranch life then and now.

Ranchers might dub a major weather front a “million-dollar storm,” referring to the costs it wrings in lost crops or livestock. Perhaps it’s a storm that deposits more than a foot of heavy, water-laden snow on crop and pastureland just when grass needs to start growing, or one that drops snow deep in the fall or during calving season, weakening and killing newborn animals. Ranchers perpetually worry about the weather they cannot control, and about the animals they tend and depend on for a living.

Ranch work is often generational. Many of the men and women riding for such big ranches as Wagonhound—the 300,000-acre spread outside Douglas, Wyo., depicted on the following pages—learned their craft riding alongside their fathers or mothers and sometimes grandparents. Many then share the work and lifestyle with their own children and grandchildren. The best hands care for the land and stock as if they owned them. They do the work with excellence because they love the land and ride for a brand.

A French-born photographer from New York may seem an unlikely person to document life on a Wyoming ranch, and Anouk Krantz admits she initially came to Wagonhound with little understanding of what she saw through the viewfinder. “All my knowledge about the cowboy around this Western way of life were all sort of misconceptions,” she came to realize. “Once I put my foot through the door, I realized this culture wasn’t dying, but was very much still alive.” Wyoming’s wide-open ranchlands, “the power of nature, these amazing landscapes,” proved her inspiration.

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch

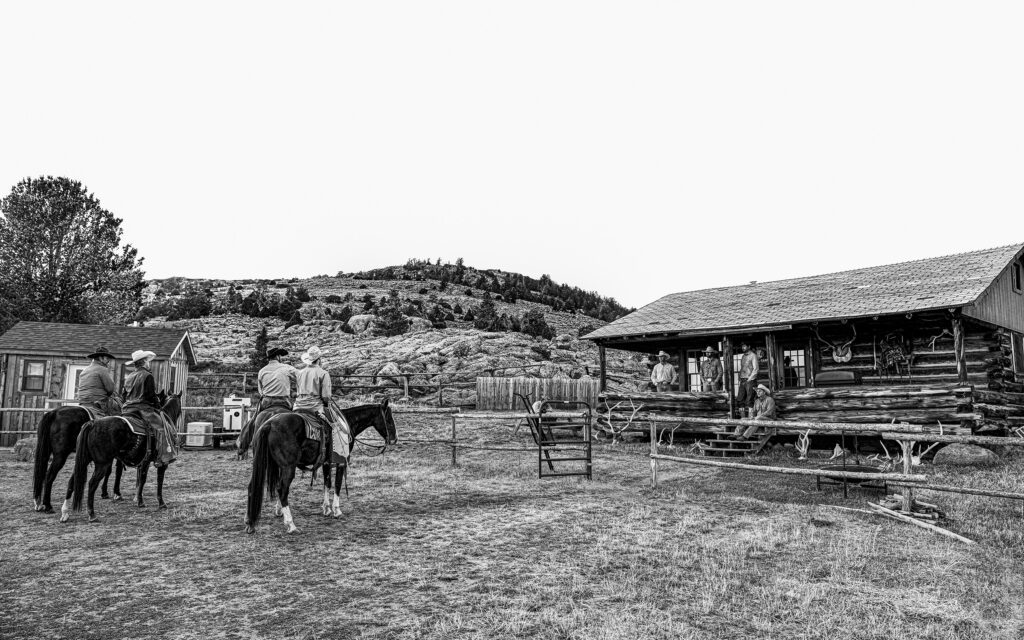

It took photographer Krantz most of a day to fly from her hometown of New York City to Denver and then to drive north to the Wagonhound in east-central Wyoming, which she deems “one of the most isolated, remote places in the country.” The familiar welcome she received is akin to that captured in her image above of a group of riders returning to waiting fellow hands at the ranch bunkhouse. Anouk’s connection to Wagonhound “started with one piece of paper with one phone number of one rancher in Texas. He introduced me to his friends, and they introduced me to their friends.” Though a stranger to ranch life, she soon found a “connection with this land, freedom, independence.” Wagonhound headquarters is about an hour west of Douglas in the midst of an isolated landscape “like the wilderness.”

Come and Get It

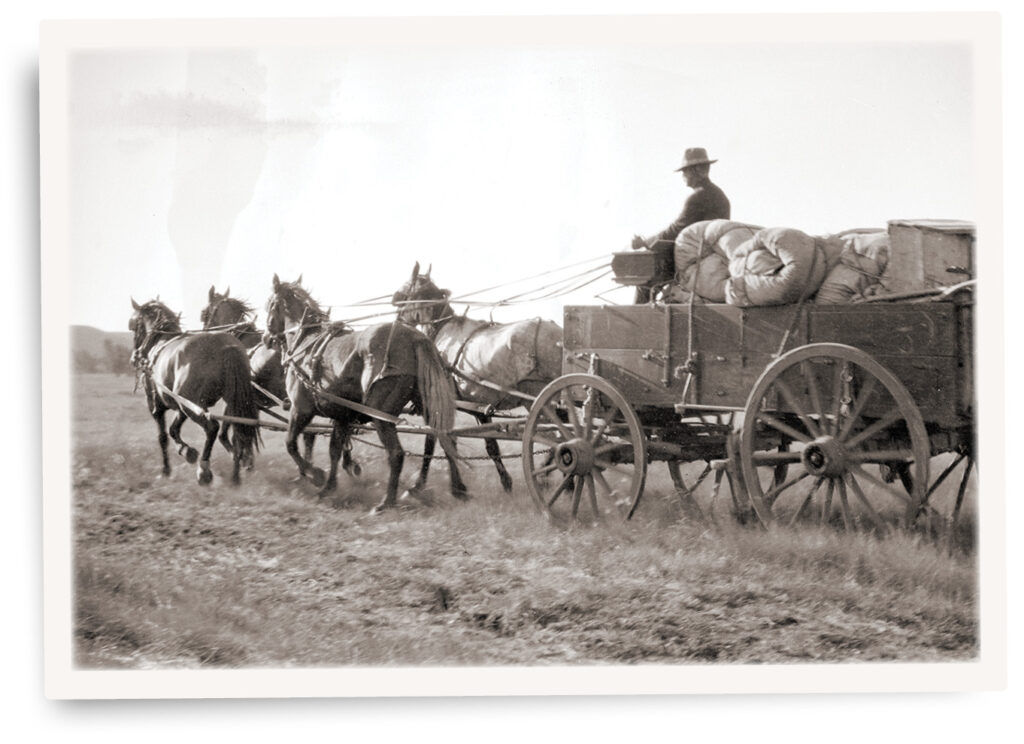

Though a ranch’s mobile kitchen may be better equipped today than when the cowboys at left in Rawlins, Wyo., spread out behind their waiting chuck wagon, eating grub from a tin plate is a ritual that carries over from the 1870s–’80s heyday of open range trail drives. “Cookie” is still expected to dish out hot meals on time for busy cowboys to eat while spread out on the ground, their horses at the ready. Anouk soon earned their respect when she proved willing to follow them at all hours. “When you are thinking about what these people are doing from dark to dark,” she says, “they are caring for their herds, but they have to do it within their surroundings. I wanted to bring that into my pictures.”

Riding for the Brand

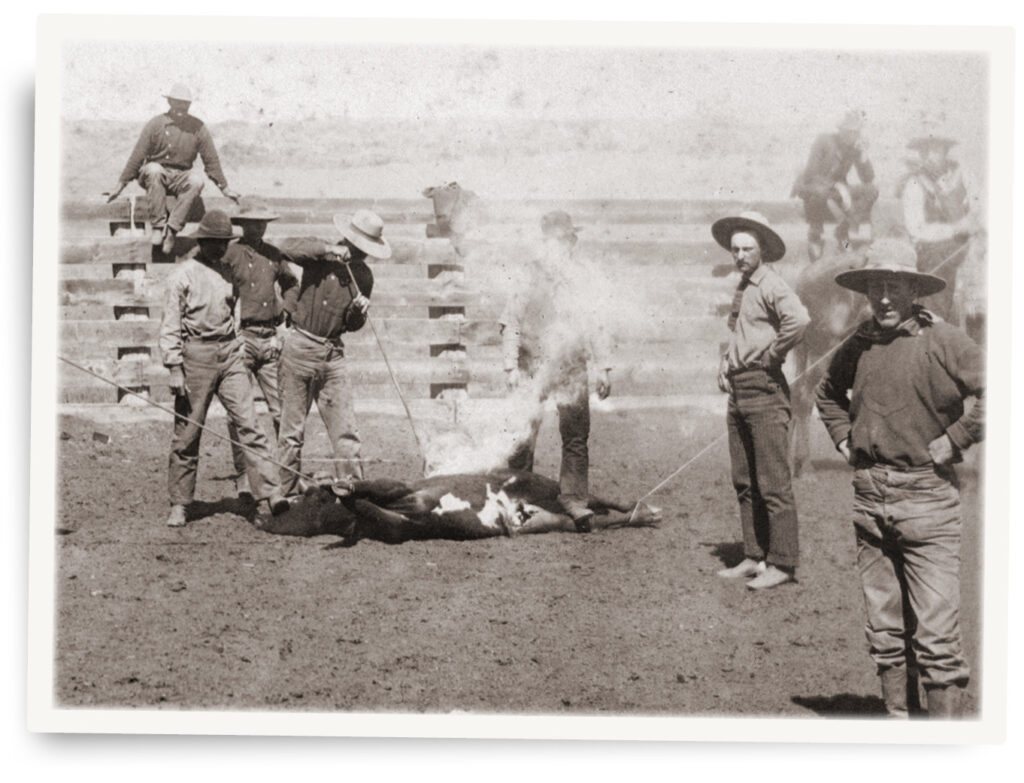

A cowhand’s tasks—corralling, roping, castrating, branding—haven’t changed much from time of the 1890s Wyoming roundup captured below. Neither has the clothing or gear. A hand doesn’t choose clothing based on style but practicality. You’ll never see cowboys at a branding wearing short sleeves. Likewise, they’ll have on sturdy jeans, work boots and, more so today, a pair of leather chaps like those above to protect their legs from kicking calves, rope burns and the stray hot branding iron. Hat styles have become more of an individual choice, but wide brims remain necessary to shield one from the sun or keep rain from running down one’s neck.

In Wyoming, by the way, the term “cowboy” is gender neutral, as applicable to the women and girls as the men and boys who ride, rope and work cattle. That said, on the Wagonhound most ranch wives work as teachers or nurses in town. They may throw in a hand at brandings, but the daily operations are mostly men’s work. The two years Anouk spent at the Wagonhound allowed her to follow these busy men and women as they gathered and branded and otherwise did their daily chores. “I was able learn how they run a ranch, how hard they work, how much it takes to do all this,” she says. “And their deep affection and love for the land, for the animals, the cows, the calves, their dogs and their horses. It all works together in such a harmony.”

Follow the Wagon Ruts

The ranch itself inspired every photograph in the book. “It’s the scale of the land, the sky, the air we breathe and mother nature,” Anouk says. “The land came first, and then we came. To me it’s very important. I think that is what still inspires people from around the world to connect with the American Western landscape.” In the 1800s hundreds of thousands of emigrants drove and followed covered wagons across these foothills along the Oregon, California and Mormon trails. The ranchers who staked claims after approval of the 1862 Homestead Act and the cattleman who trailed the first herds north from Texas into Wyoming also used wagons to haul food and supplies. Wagonhound’s true expanse is revealed above, as pickups and horse trailers crossing the ranch in line seem like child’s toys.

Learning the Ropes

Ranch life is multigenerational. Often a roundup or branding crew includes grandma and grandpa, mom and dad, sons and daughters, all riding and working side by side. Little ones might ride saddles their own parents used when they were small. The best babysitter on a ranch remains a steady, older horse named Dunny or Brownie or even Sweet Pea. The best such horses can be depended on to be gentle around kids but still able to manage quarrelsome steers. If a kid doesn’t know how to push cows down a trail or out of brush, but the horse does, then that’s a partnership that will get the job done. When adults involve their children in the chores—the kids usually consider it fun—they are not only passing on a legacy, but also instilling a work ethic and an appreciation for stewardship of the land, work animals and livestock. Among Anouk’s revelations as she photographed the Wagonhound were how hard people work and how they work together as a community with their families and neighbors. But her biggest discovery was how much they truly cared for the land. “How they use pasture rotation, a wonderful way to let the earth breathe, rest,” she says. “What they are doing for our earth is unknown to most people.”

Candy Moulton, executive director of the Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame, was reared on her grandparent’s homestead near Encampment, Wyo.

Photographer Anouk Masson Krantz’s book, Ranchland: Wagonhound, received the 2023 Western Heritage Award for best art/photography book from National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.