Stumping in New Hampshire:

Long before its famous primaries, the Granite State was an election player

In a year that marked the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, much was written about his greatness, his trials and his legacy. More than 70 books were published in 2009 alone, and Lincoln still ranks as the most written-about figure in American history. Yet it always fascinates to discover how people seeing him for the first time responded to how he looked, acted and spoke.

Orators of the period often employed lofty literary allusions and strove for high drama to make their points. Speeches were as much for entertainment as edification, and frequently had more in common with performance than politics. Lincoln’s own distinctive style, however, owed less to entertainment than to what one New Hampshire newspaper editor called his “irresistible logical force and power.” A wonderfully intimate glimpse of Lincoln the public speaker comes to us from his trip to New Hampshire in 1860, when he visited his eldest son, Robert, at Phillips Exeter Academy.

Orators of the period often employed lofty literary allusions and strove for high drama to make their points. Speeches were as much for entertainment as edification, and frequently had more in common with performance than politics. Lincoln’s own distinctive style, however, owed less to entertainment than to what one New Hampshire newspaper editor called his “irresistible logical force and power.” A wonderfully intimate glimpse of Lincoln the public speaker comes to us from his trip to New Hampshire in 1860, when he visited his eldest son, Robert, at Phillips Exeter Academy.

The 51-year-old Lincoln arrived in late February, fresh from the historic appearance at New York’s Cooper Union that helped lay the groundwork for his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. Word of the sensation he created in New York generated enthusiastic audiences wherever he went. During a three-day period, he delivered a total of four speeches in the Granite State. His last address, according to contemporary reports, stretched over two hours.

On March 1, he spoke at a “Grand Republican Rally” at Phenix Hall in Concord. Although the strongly Democratic Nashua Gazette dismissed Lincoln’s speech as “dull, heavy [and] sectional,” nothing was further from the truth. Lincoln’s Concord speech, by all reports, was brilliant. His main topic was the incendiary issue of the expansion of slavery, and he spoke forcefully and convincingly, encouraging challenges from his listeners and reveling in the discussion that followed. Lincoln tempered the strength and eloquence of his words with humor and homilies, and he kept the audience packing the hall enthralled until the end. When he finished, he was loudly cheered and given a standing ovation. The local newspaper described the speech as “masterly and massive,” calling Lincoln a “master of his subject and of his audience.”

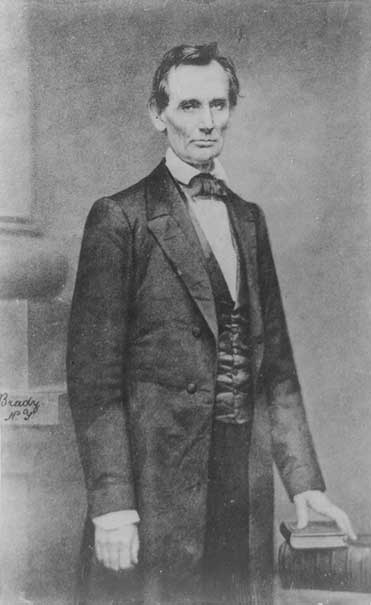

Republican State Chairman Edward H. Rollins, hearing Lincoln for the first time, was duly impressed: “It is worth a long walk to see the man….Long, lank, and awkward, he presents a picture of the real Yankee,” Rollins observed. “His voice is pitched on a high key and is anything but musical, but these oddities and peculiarities which would seem to detract from the efficiency of an orator all go to gain the sympathy of his hearers and to make his speeches what they are.”

Lincoln traveled on to Manchester and Dover, where his addresses again inspired awe in his listeners. “He seems to forget all about himself while talking, and to be entirely engrossed in the welfare of his hearers,” reported the Manchester Daily Mirror. “He does not try to show off, to amuse those of his own party, but addresses all his arguments in a way to make new converts.”

At one point, he stressed that those who favored the expansion of slavery into the territories would be “squelched,” and as he said the word, recalled a young woman, “Lincoln came to the extreme front of the platform, raised his right arm to its full length above his head, with the last word closed his hand as if to crush the objectionable thing, leaned forward and swung his arm to the right, bringing his hand down almost to his feet.”

“Distinctly I remember the long arms swinging, the mask-like face, the quick turn of the body to right and left as he drove home a red hot rivet of appeal; the mobile change of his face from gravity to mirth, suggested rather than exhibited,” another witness later wrote.

Lincoln delivered the fourth and last speech at Exeter, near his son’s school. Several of Robert’s classmates attended. As one of them later recalled, the elder Lincoln did not cut an imposing figure. He was “tall, lank, awkward; dressed in a loose, ill-fitting, black frock coat, with black trousers, ill-fitting, and somewhat baggy at the knees,” one of them later remembered. “His hair was rumpled, his neckwear was all awry…. Mr. Lincoln’s legs were so long he had trouble in disposing of them and twisted them about under the chair to get them out of the way. One of the boys leaned over and whispered, ‘Don’t you feel kind of sorry for Bob?’ We did not laugh. We were sympathetic for Bob because his father did not make a better appearance. The girls whispered to each other: ‘Isn’t it too bad Bob’s got such a homely father.’”

People generally underestimated Lincoln, until they heard him speak. He would begin with an almost reluctant deliberation, made peculiar by that high, squeaky, Midwestern twang; as one observer in Exeter commented, “For the first three or five minutes, I’d have given anything to be at home. But after he…told a story or two, he began to attract my attention. In ten minutes, I was glad I was there.” As he warmed to his subject, Lincoln carried the audience along with him.

The same student who had earlier expressed pity for his friend Bob went on to observe that “[Lincoln] rose slowly, untangled those long legs from their contact with the rounds of the chair, drew himself up to his full height of six feet, four inches, and began his speech. Not ten minutes had passed before his uncouth appearance was absolutely forgotten by us boys and, I believe, by all of that large audience. For an hour and a half he held the closest attention of every person present.” Although the young man had initially thought Lincoln “the most melancholy man I had ever seen,” he opined that when Lincoln invoked humor, “his face lighted up and the man was changed. There was no more pity for our friend Bob; we were proud of his father; and when the exercises of the evening were over…we were the first to mount the platform and grasp him by the hand. I have always felt that this was one of the greatest privileges of my life.”

The same student who had earlier expressed pity for his friend Bob went on to observe that “[Lincoln] rose slowly, untangled those long legs from their contact with the rounds of the chair, drew himself up to his full height of six feet, four inches, and began his speech. Not ten minutes had passed before his uncouth appearance was absolutely forgotten by us boys and, I believe, by all of that large audience. For an hour and a half he held the closest attention of every person present.” Although the young man had initially thought Lincoln “the most melancholy man I had ever seen,” he opined that when Lincoln invoked humor, “his face lighted up and the man was changed. There was no more pity for our friend Bob; we were proud of his father; and when the exercises of the evening were over…we were the first to mount the platform and grasp him by the hand. I have always felt that this was one of the greatest privileges of my life.”

Abraham Lincoln, the unlikeliest of presidential candidates, charmed, cajoled and debated New Hampshire into supporting him. Seven of New Hampshire’s 10-member delegation to the Republican convention in Chicago voted to nominate Lincoln. And to the surprise of many—quite possibly including the candidate himself—when it came time to vote for their president, New Hampshire shifted by Election Day from a Democratic to a Republican state, giving Lincoln nearly 57 percent of the popular vote.

Historian Ron Soodalter is also a flamenco guitarist, scrimshander and folklorist.

Article originally published in the November 2010 issue of America’s Civil War.