Often overlooked in the history of firearms out West was the H&R line of revolvers, innovative spur-trigger models with origins back East. In 1871 Massachusetts-based gunmakers Gilbert H. Harrington and Frank Wesson (brother of Daniel B. Wesson of Smith & Wesson fame) formed a short-lived partnership under the name Wesson & Harrington. Four years later Wesson branched out on his own and sold his shares to Harrington. By 1876 Harrington and former Wesson employee William A. Richardson had forged the namesake partnership destined to become one of the longest surviving firearms manufacturers in the region, though not until 1888 did Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. formally incorporate in Worcester, Mass.

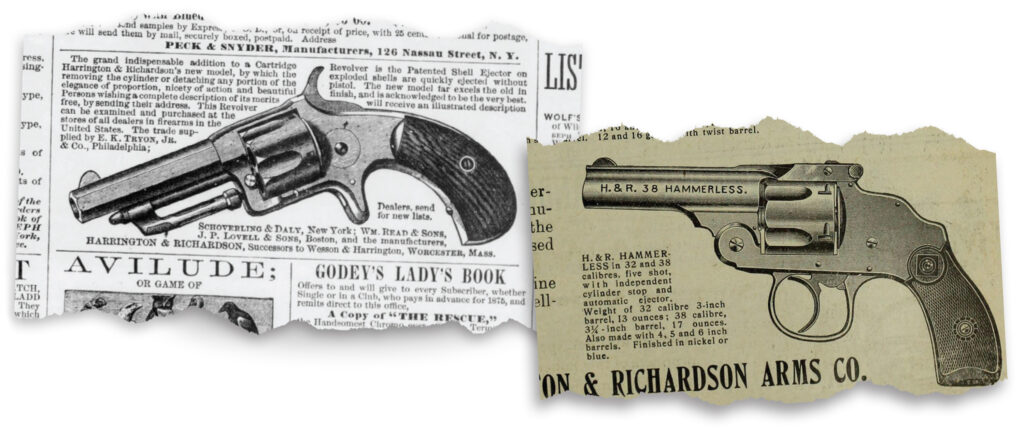

Starting up production in 1877, H&R produced untold millions of revolvers, from early single-action models using rimfire cartridges to later double-action models using .32 and .38 Smith & Wesson centerfire cartridges. The H&R line expanded and improved over time, making both solid-frame and top-break revolvers.

Small-frame pocket “wheel guns” were popular in the Old West, most often as an extra measure of life insurance. By the late 1870s the double-action revolver came into vogue. As a shooter no longer needed to cock the hammer before each shot, such revolvers were considered the “semiautomatics” of their day. H&R entered the scene with its five- or six-shot Model 1880 solid-frame double-action revolver in .32 and .38 S&W calibers. By decade’s end the company’s top-break models had become the mainstays of its line.

Among H&R’s leading competitors, Smith & Wesson had pioneered the top-break action in the United States with its larger .44 S&W Russian and American and .45 S&W Schofield models, which ejected empty cases out of the cylinder on opening to reload—a welcome time (and, potentially, life) saver. Another of S&W’s revolutionary double-action revolvers was its small-frame safety hammerless revolver. Introduced in 1887, the design caught on.

Already at work on a similar design, H&R soon patented its own hammerless revolver with enough internal differences to avoid any infringement on S&W’s model. The latter’s version was nicknamed the “lemon squeezer,” a moniker eventually applied to all hammerless double-action models.

As the Old West gave way to the turn of the century, such small-frame double-action revolvers appealed to many a ranch hand who, given weight considerations and tamer times, had grown weary of lugging around heavier hardware. In photographs of settlers bound for the Cherokee Strip land run in 1893 one can spot, in addition to the standard Sharps or Spencer rifle, small-frame double-action revolvers in many a holster. Messengers and detectives with Wells Fargo & Co. and other favorite targets of highwaymen were also fond of carrying a top-break small-frame double-action revolver or two. A period of especially brisk sales for H&R accompanied the 1896–99 Klondike Gold Rush to the District of Alaska and Yukon Territory. Presumably for protection against such ne’er-do-wells as notorious con man Soapy Smith and cohorts, scores of gold seekers carried the low-cost H&R hammerless double-action revolver. By then the company had plenty of competition in the small-frame revolver niche from such respected makers as Hopkins & Allen, Forehand & Wadsworth, Iver Johnson and Thames Arms. Among other noted users, Frank Hamer—the famed Texas Ranger who finally stopped Depression-era outlaw duo Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, killing them from ambush near Gibsland, La., on May 23, 1934—carried a small-frame, five-shot, .38-caliber double-action pocket revolver in addition to full-size sidearms.

Though the patent for H&R’s hammerless safety revolver dates from 1895, it is difficult to date individual guns, as the company used run-on serial numbers and didn’t keep meticulous records. In addition to its popular revolvers, H&R also produced single- and double-barrel shotguns, including the first American-made hammerless double-barreled shotgun based on the British Anson & Deeley action, as well as the single-shot “Handy-Gun,” a short-barreled shotgun with a pistol grip that was dropped from production in 1934 following passage of the National Firearms Act, which outlawed such “gangsterish” configurations. H&R was among the few American firearms manufacturers with unprecedented longevity. It continued to produce well-made, no-frills guns for the money until shuttering its doors in 1986 after more than a century in business.