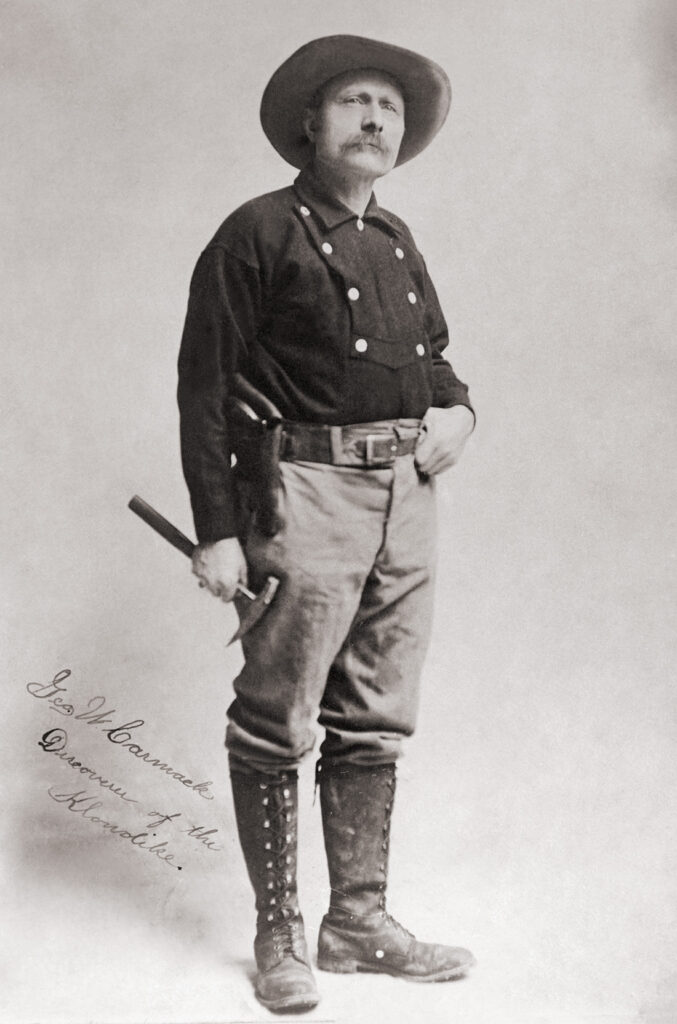

George Carmack strutted into Bill McPhee’s smoke-filled saloon in the settlement of Forty Mile, Canada, at the confluence of the Fortymile and Yukon rivers. Days earlier, on Aug. 16, 1896, Carmack and his Tagish brother-in-law, Keish (aka “Skookum Jim” Mason), and nephew Káa Goox (aka “Dawson Charlie”) had found gold far to the east on Rabbit Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River. Carmack ordered a round of drinks for the house, shouting, “There’s been a big strike upriver!” Few of the bar patrons paid much mind. After all, it was “Lying George” doing the talking. But the gold nuggets the excited prospector slapped down to pay for the drinks did catch their attention.

These “Sourdoughs,” so named for the fermented dough they used to make everything from bread to flapjacks, were a unique breed. They drifted north by ones and twos when most Americans were heading west to the Pacific. They liked to claim they were prospectors, but only a few actually found gold.

They were also extremely eccentric. Four partners kept a moose in their cabin as a pet. Others, like Frank Buteau, rigged up sails to propel their sleds—in Buteau’s case because he couldn’t afford dogs. Another hardy, albeit penniless, soul was rumored to have fashioned dental plates for his fronts from tin spoons and teeth pulled from the skulls of a mountain sheep, a wolf and a bear he’d shot. With typical Sourdough gusto he then stewed and ate the bear with its own teeth.

These adventurers barely peppered the vast region. The 1890 federal census recorded only 31,795 residents (including 4,303 whites and 23,274 Native Alaskans) in the adjacent 663,000-square-mile District of Alaska, whose governor was appointed by the president of the United States. Little more than 2,000 souls dwelled along the banks of the 1,980-mile-long Yukon River itself, which flows westward through Canada’s Yukon Territory and Alaska to the Bering Sea.

As soon as Carmack left the bar, or perhaps before, bystanders inquired at the recorder’s office about the location of Carmack’s claim. Time was ripe for a major strike; the value of gold shipments from the Yukon had increased from $30,000 in 1887 to $800,000 in 1896. Within days some 1,500 Sourdoughs descended on the Klondike River, just upstream from where it empties into the Yukon. Taking its name from the river, the gold-bearing region of central Yukon Territory became known as the Klondike. Through the bitter winter months of 1896–97 each prospector worked his solitary claim, having scant communication with the outside world.

With the spring ice breakup hundreds of miners rafted down the Yukon to the sea. Many hadn’t emerged from the interior for decades. Nearly all had been destitute the previous spring. At the former Russian trading port of St. Michael, Alaska, they boarded the southbound coastal steamers Portland and Excelsior. On July 14, 1897, Excelsior docked in San Francisco, unloading more than a dozen free-spending Sourdoughs who ignited rumors of quick wealth. Two days later 5,000 people crowded Seattle’s waterfront to greet Portland. The Seattle Post Intelligencer published an extra edition with reporter Beriah Brown’s news the ship had brought “more than a ton of gold” from the Klondike.

The Klondike Gold Rush was on.

Thousands Set Out

Gold fever swept Seattle. Thousands of hopefuls jammed the streets to elbow and snarl their way to the docks. Store clerks quit by the hundreds. Streetcar service ground to a halt as operators resigned on the spot. Hotels booked up and restaurants were packed to bursting as people flooded to town. There was also an epidemic of stolen dogs, presumably smuggled north for use pulling sleds. Meanwhile, a ragtag fleet composed of anything that would float hastily assembled for a return voyage to the ports of entry in Alaska.

Seattle Mayor W.D. Wood was attending a conference in San Francisco when he read about Portland’s cargo. He promptly telegraphed in his resignation as mayor, raised $150,000 and bought a steamer to take him and paying passengers to St. Michael. John McGraw, president of Seattle’s First National Bank and the state’s former governor, booked passage on Portland for its return voyage. One man dying of lung disease boarded Portland, insisting to distressed relatives he would rather die trying to get rich than rot on his deathbed in poverty.

Within months of the news more than 40 ships out of San Francisco alone were making regular passages to and from Alaska—no matter that many had been condemned and were waiting to be broken up in local shipyards. More than 100,000 people would ultimately set out for the Klondike.

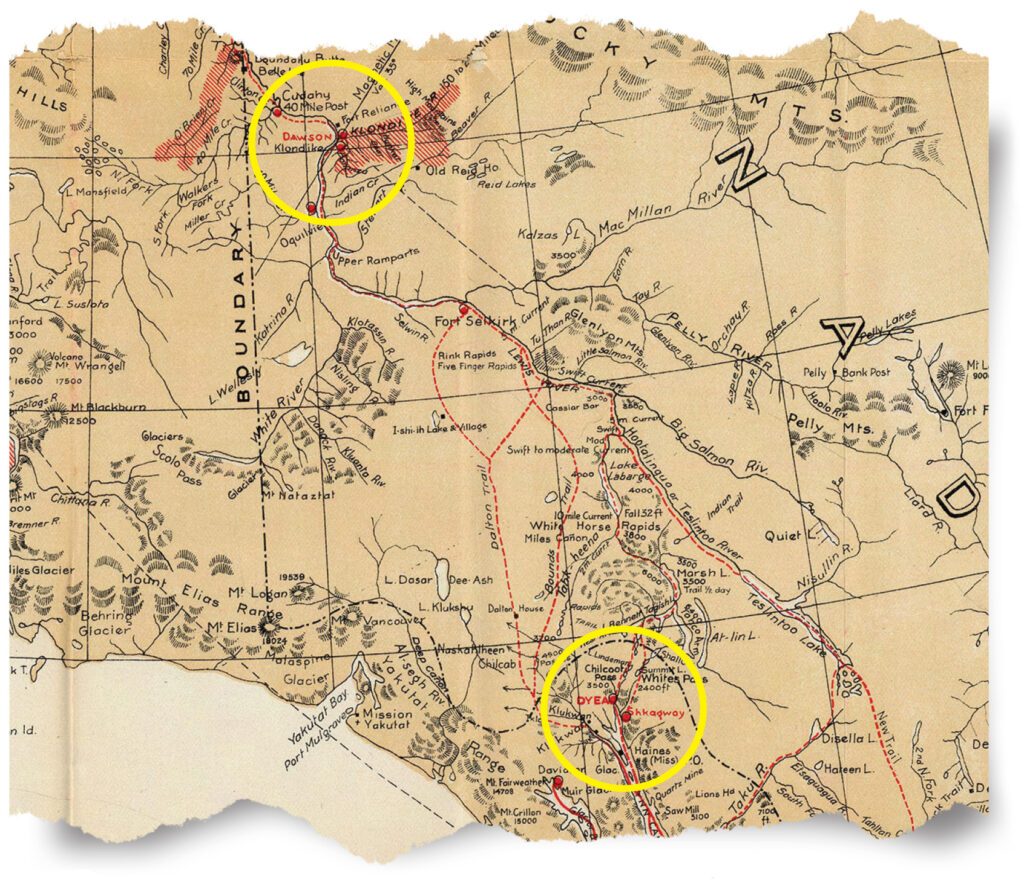

The gold rush drew such Old West refugees as lawman Wyatt Earp, Tex Rickard and Frank Canton; madam Mattie Silks; frontier scouts Jack Crawford (“Poet Scout” of the West) and Luther “Yellowstone” Kelly; and Indian fighter “Arizona Charlie” Meadows. They mingled with thousands of inexperienced men and women willing to stake everything on a shot at striking it rich as the United States emerged from a horrific economic depression. People who had never lived off the land—schoolteachers, bank tellers, unemployed seamen, basketball coaches and single mothers with children to feed—all headed north. In 1887 steamship captain Billy Moore—who, guided by Skookum Jim, had pioneered the White Pass trail into the Canadian interior—claimed a 160-acre homestead at the mouth of the Skagway River. But the crush of follow-on prospectors ignored his claim. When surveyors of the city of Skagway later platted a street straight through the middle of Moore’s house, the grizzled old captain emerged swinging a crowbar only to be subdued by a mob.

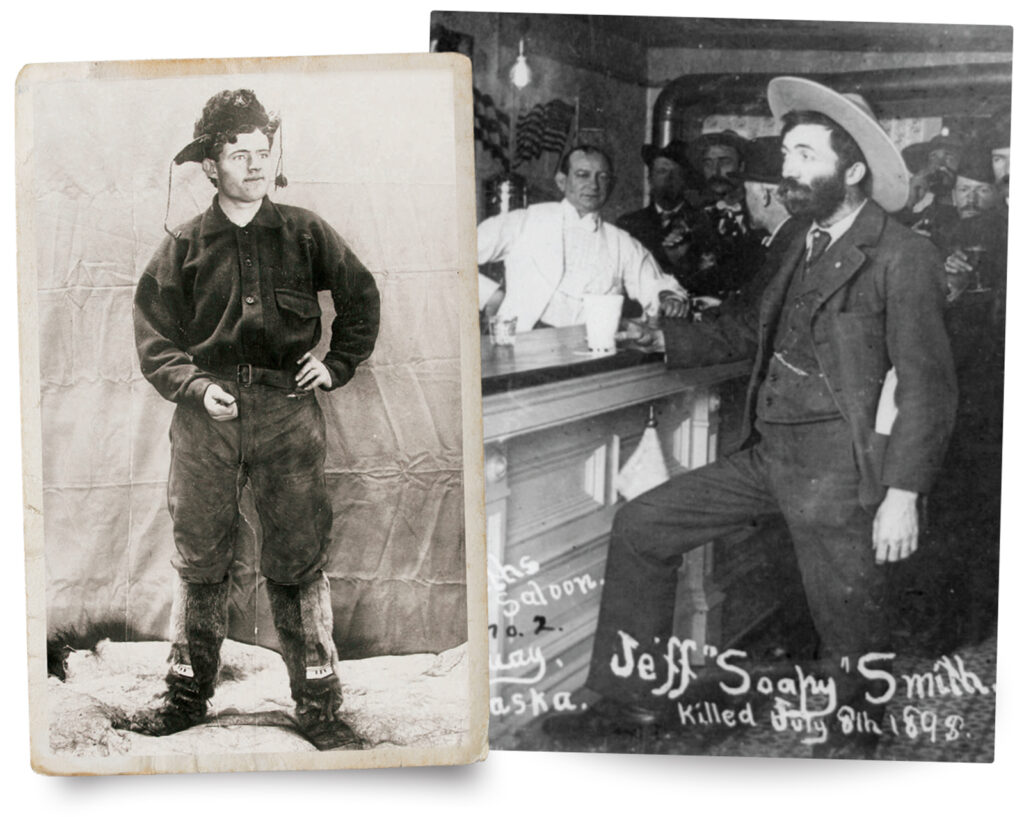

Arriving in Skagway that summer, a young Jack London found streets of muddy ruts lined with tents, huts and hastily constructed wood-frame structures. Laughter, screams and sporadic gunfire filled the air. Murders were almost a nightly occurrence, and prostitutes conducted business in full public view. Famed Yukon Territory officer Sam Steele of Canada’s North-West Mounted Police deemed Skagway “little better than a hell on earth.”

London was just 21 when he arrived in Skagway. Hollywood has long portrayed him as an innocent, but that wasn’t true. Young London, whose birth father had deserted his pregnant mother, went to work delivering papers, sweeping saloons, setting up pins at bowling alleys and working in a cannery all by the age of 13. After trying his hand at pirating commercial oyster beds, he hired out to the Californian Fish Patrol to hunt down the very oyster pirates with whom he’d worked.

At age 17 he shipped for Japan, en route encountering a dynamic mariner and sealer who became the model for his 1904 novel The Sea-Wolf. On his return stateside he marched across the country with other socialist activists to Washington, D.C. In Buffalo, N.Y., he was arrested for vagrancy and served 30 days in jail.

By the time of the Klondike Gold Rush he was starving in his chosen profession as a writer. When he mentioned the strike to his 54-year-old brother-in-law, James Shepard, the latter offered to grubstake the 21-year-old if Shepard could join him. London agreed. On July 25, 1897, the unlikely pair sailed from San Francisco aboard the steamship Umatilla. Aboard they fell in with carpenter Merritt Sloper, placer miner Jim Goodman and Fred Thompson, who kept a journal of their adventures. On August 2 the five disembarked at Juneau and canoed to Skagway from there.

By then Skagway was under the thumb of a ruthless gang controlled by one Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith—a con man, or “sure thing man” in Western parlance. Having ventured to Alaska from Denver, he and his cohorts had first moved in on Wrangell, a backdoor port to the Klondike a few hundred miles down the coast. Moving north, Soapy had considered taking over Dyea, just upriver from Skagway, but former lawman turned trader John J. Healy had proved too powerful an opponent, so Smith and his men settled on Skagway. Soapy’s saloons sold watered down whiskey to northbound prospectors, while his henchmen ran a protection racket on competing saloons.

En route to Alaska aboard the steamship Utopia the gang had helped the ailing Captain “Dynamite Johnny” O’Brien put down a mutiny. Johnny returned the favor by allowing Soapy and his men to travel free on O’Brien’s growing fleet of ships. While aboard Soapy’s men would target a mark worth plucking and then pounce amid the crowded frenzy when the ship disembarked in Skagway. O’Brien had a massive fleet, all Skagway bound. Most Klondike prospectors came north on one of his ships, and each had Soapy men on its manifest.

Soapy ran a dockside information booth that sold newcomers maps of the White Pass, the best campsites helpfully marked with X’s. What they didn’t know is that Soapy’s men were waiting at those X’s to rob and even murder them. Perhaps Smith’s “best” con was his Dominion Telegraph Service—not that Alaska had telegraph service. Dominion’s line comprised a section of wire strung from town and nailed to a tree in the deep woods. Newcomers who didn’t know any better would rush into the telegraph office and, for a fee, “wire home” with news of their arrival. Some hours later a convincing runner would locate the customer and hand him a reply—almost always a plea to immediately wire home money. Presented with such a desperate request, the mark would continue to open his wallet until someone set him straight.

Braving the Pass

On the Taiya River some 5 miles north of Skagway, Dyea sits at the foot of near vertical 3,759-foot Chilkoot Pass. Some 40,000 would-be millionaires confronted the pass in the first year of the gold rush, Dyea’s population swelling from 1,000 to 8,000 by the spring of 1898.

Presented with a choice of fending off the Smith gang in Skagway or trying their luck in the pass, London and his friends chose to trek to Dyea and scale the Chilkoot into the Klondike. Soon after setting out, they met with a horrifying scene. The landscape was littered with dead and dying horses, as few of the 3,000 horses urged up the arduous trail that autumn survived. Inexperienced owners beat the animals, many of which dropped from exhaustion, slipped in the mire and fell to their deaths. Others succumbed to wounds rent by jagged rocks.

“The horses died like mosquitoes in the first frost,” London wrote, “and from Skagway to [Lake] Bennett they rotted in heaps.”

On reaching the top of the pass, the party encountered Mounties who demanded each prospector have 1,000 pounds of supplies before proceeding into the Yukon. It took London and his friends 20 days to porter sufficient supplies over the summit, an effort that broke the health of his brother-in-law, who returned to San Francisco. At one point while hefting his goods upslope, London spotted a pair of boots sticking out of a snowbank. He tried picking them up only to find them still attached to the feet of a man who’d been buried in an avalanche minutes earlier. London and others pulled the very much alive and grateful man free.

Trails from both passes ended at Lake Bennett, which spans the border of British Columbia and Yukon territories. A vast tent city rose on its shoreline as 30,000 hopeful prospectors waited for the frozen lake to thaw so they could raft the 500 or so miles downstream to Dawson and the Klondike. On May 29 the ice broke, and by day’s end 800 assorted boats and rafts had set off. Within 48 hours 7,124 had set sail. All had to shoot a series of rapids patrolled by the Mounties, who were on hand to recover the dead.

London and party tempted fate on the rapids. He and his party shot through Miles Canyon Rapids without any problems, though their boat rocketed downstream within 6 feet of the canyon’s granite walls. After helping a couple get through, they took on Whitehorse Rapids. Amid that stretch a whirlpool captured their craft in its spin, nearly throwing everyone overboard. London lost all rudder control. Only by chance did the whirlpool just as suddenly pop their boat free.

During the first winter of the gold rush starvation had almost wiped out Dawson. Too many people had arrived without sufficient food—hence the Mounties’ stiffened requirements. Saloonman McPhee of Forty Mile fame turned his Dawson saloon into an after-hours shelter for the homeless, whom he fed. The population reached 500 by year’s end 1896. Six months later it had grown to 5,000. By year’s end 1897 it boasted a population approaching 20,000, its residents almost all hailing from the United States.

Rumor had it Dawson again lacked sufficient food stores for the coming winter. That prompted London and party on October 8 to pull ashore on Split-Up Island, at the mouth of the Stewart River some 75 river miles short of their destination, so as not to be around whatever was about to befall Dawson. They would overwinter in one of the many abandoned cabins. It was there London’s observations inspired his short story “To Build a Fire.”

After a 47-day visit to Dawson, marked by much drinking and camaraderie, London and friends returned to their isolated cabin, and soon winter temperatures plunged to minus 40. For months their daily routine consisted of collecting ice, chopping firewood and shoveling snow, as well as preparing the three B’s—beans, bread and bacon—that sustained most overwintering prospectors. By spring London’s gums were swollen and bleeding. He had scurvy and still no gold.

Fortunes Gained and Lost

Of the 100,000 hopefuls that set out, roughly 35,000 reached the Klondike. Among those only a few thousand found any gold, and only a couple hundred of those in quantities enough to truly be considered “rich.” Whether they were wide-eyed young adventurers like London, weathered lawmen, teachers, bank tellers or prostitutes, Dawson’s varied residents shared a certain kinship as they slogged its muddy streets past saloons, warehouses, whorehouses and churches. For better or worse, they had stuck it out, while the majority had turned back.

Some of the prospectors did quite well. “Swiftwater Bill” Gates’ claim was literally knee deep in gold. He spent his Klondike fortune but found another in Nome after having returned to Alaska with one especially irate mother-in-law in hot pursuit. In one two-hour span Jim Tweed found $4,284 in nuggets on his claim, while Frank Dinsmore took $24,489 in gold in a single day. Albert Lancaster averaged $2,000 a day over eight weeks. Brooklynite Gus Mack found enough gold to start Mack Trucks with his brothers, and with a fortune earned by entertaining Klondike miners Sid Grauman opened his namesake Chinese Theater in Los Angeles.

Others followed more traditional paths. Lying George Carmack invested in Seattle real estate and died a wealthy man. So did Clarence “C.J.” Berry, who returned from Alaska with $1.5 million in gold. Outside his cabin in the Yukon he’d placed a coffee can containing rough nuggets, a whiskey bottle and a sign reading, Help Yourself. Prospector turned philanthropist Tom Lippy donated land to expand Seattle General Hospital. Lawman turned saloonman Tex Rickard left Alaska to build the third iteration of New York City’s Madison Square Garden, while playwright and con man Wilson Mizner opened the Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles.

Dawson prostitutes Silks and “Diamond Tooth Lil” Davenport made a fortune mining the miners, while “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, “Diamond Tooth” Gertie Lovejoy and other dance hall girls also cleaned up. Two won notoriety for quite literally selling themselves. Grace Drummond sold herself to Charley “Lucky Swede” Anderson for $50,000, and Bill Gates bought Gussie Lamore for $30,000, her wedding present determined by her literal weight in gold.

Others’ fortunes slipped through their hands. Through no fault of his own Anderson lost his when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed his real estate holdings. He died in 1939 pushing a wheelbarrow at a sawmill for $3.25 a day. Anton Stander built Seattle’s Stander Hotel before liquidating the rest of his fortune in alcohol. Pat Galvin spent his fortune investing in riverboats and was battered into bankruptcy by the rough Yukon.

London made it out of the Yukon in 1898 by sailing downriver to the Bering. By the time he set foot back in San Francisco, he had only $4.50 in gold in his pockets but a wealth of stories to write.

By then homebound prospectors—fed up with being scammed, robbed and worse by the Smith gang when they returned south through Skagway—were largely leaving the Klondike westbound via the Yukon River. On the evening of July 8 the town’s equally fed up vigilance committee met on the wharf to discuss what to do about Soapy. When Smith came to break up the meeting, he engaged in a shootout with a man guarding the dock. Both were killed.

On the night of April 26, 1899, fire broke out in the room of a Dawson dance hall girl, and the city was soon ablaze. Some 117 buildings, from the most ornate hotels to riverside shacks, were reduced to ashes. Most of the Klondike goldfields had been claimed by then.

When word came later that spring that the very landing beaches of Nome held gold, 8,000 residents abandoned Dawson for the new strike.

The Klondike Gold Rush was over.

For further reading on this topic author Mike Coppock recommends Coming Into the Country, by John McPhee, and Alaska: Saga of a Bold Land, by Walter R. Borneman.