His fans compare it to the Second Coming, his enemies to the second coming of January 6. So far Donald Trump’s 2024 run for president seems most like a 1980s arcade game with an outlandish hero bouncing among indictments and own-goal interviews in pursuit of the big prize.

Trump is not the first ex-president to try to win one more time. (He does not think he is quite an ex-president, of course, since he believes contrary to all evidence that he won in 2020.) For nearly 200 years losers and voluntary retirees alike have sought to reoccupy the White House.

Five of the first seven presidents—Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Jackson—chose to step down at the end of their second terms. The one-termers had their own choices to make. After John Adams lost his reelection bid in 1800 he went home to Quincy, Mass., to lick his wounds for 25 years. His son John Quincy Adams was more ambitious. Elected in 1824 and beaten in 1828, he angled for the nomination of the new Anti-Masonic Party in 1832. JQA offered to reveal the secrets of Phi Beta Kappa, his undergraduate fraternity. The Anti-Masons were not interested. After this rebuff, he contented himself with the lesser office he already had—congressman from Massachusetts.

Another disappointed one-term president was already struggling to get back, with even more determination.

Martin Van Buren of Kinderhook, N.Y., was the first president to be born an American citizen (in 1782), and the only one whose first language was not English (his was Dutch). Van Buren rose in local, state, and finally national politics on the strength of populist principles, an easygoing manner, and hard work. He helped create the modern Democratic Party, uniting vote-rich New York with the South, and served its first champion, Andrew Jackson, as Secretary of State, then vice president. Van Buren succeeded his mentor—or had he really been his protégé?—in 1836.

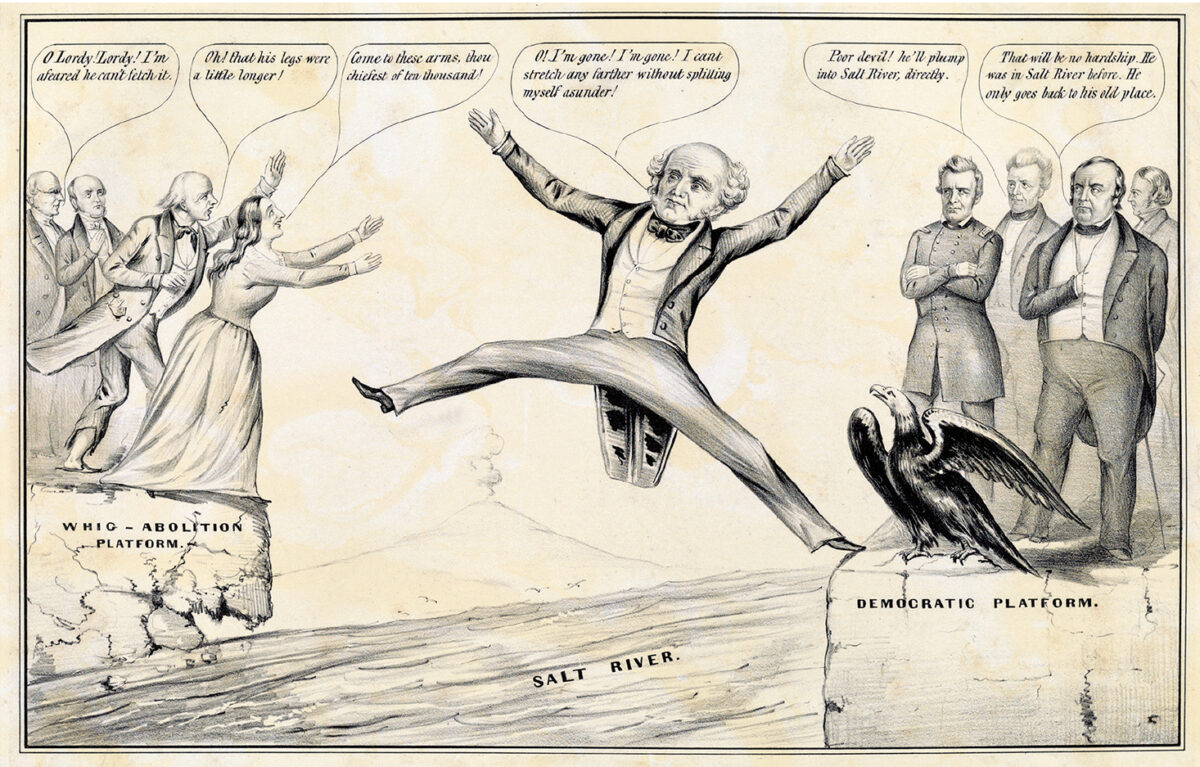

Van Buren’s term was almost immediately blighted by the depression of 1837. A new party, the Whigs, rose up to fight him. They appealed to Americans writhing under hard times by depicting Van Buren as a dude: Van Buren, son of a shabby innkeeper, had always worked a little too hard at his wardrobe. His 1840 campaign against William Henry Harrison was a disaster.

The Whigs soon encountered disasters of their own. Harrison died after 30 days in office and his veep and successor John Tyler quarreled with every other Whig. Van Buren took a nationwide listening tour in 1842—he spent one Illinois evening trading stories with a young Abraham Lincoln—and offered himself to the 1844 Democratic convention.

The party had a rule, however, that the nominee needed a two-thirds vote, not a simple majority. Although Van Buren had appeased the slaveholding South throughout his presidency, he had announced that he would not now annex the rebellious Mexican province of Texas: he didn’t want the political headache of integrating a new slave state. Angry expansionists withheld their support, and after 10 deadlocked ballots the convention turned to former Speaker James K. Polk.

Van Buren made slavery the linchpin of his last campaign, as candidate of the Free Soil Party in 1848. The party touted new territories and states whose soil for free White men, not Black slaves. Van Buren won only 10 percent of the popular vote, but that took up enough votes to prevent pro-slavery Democrat Lewis Cass from winning New York, helping Zachery Taylor gain the White House.

Throughout the 19th century, some ex-presidents, following JQA’s example, sought lower office: John Tyler was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives, Andrew Johnson to the U.S. Senate (both men died before taking office). Other exes aimed for the top: Whig Millard Fillmore, who succeeded Zachary Taylor at his death in 1850, ran in 1856 as the candidate of the anti-immigrant American (or Know-Nothing) Party. The Know-Nothings, wrote one contemporary, “came out of the dark ground, crawled up the sides of the trees, ate their foliage in the night, chattered with a croaking harshness, split open their backs and died.” Fillmore got 21 percent of the popular vote, and carried only Maryland.

Ulysses Grant, after serving two terms, took a triumphal tour of the world, and tried a third run for the GOP nomination in 1880. But the nominating convention tapped Ohio Rep. James Garfield instead. But one defeated president—like Van Buren, a New York Democrat—managed to win back the White House.

Grover Cleveland was a Buffalo, N.Y., lawyer, noteworthy for his capacity for heavy labor, and heaviness: he “eats and works, eats and works, works and eats,” wrote one reporter. He was also personally honest and a stickler for administrative responsibility: noteworthy qualities in the post-Civil War era when an enlarged government was awash with cash to spend and contracts to assign. Cleveland became successively sheriff of Erie County, Mayor of Buffalo, and governor of New York. By the 1880s the Democrats had not won the presidency for a quarter-century. They ran urban machines like New York City’s Tammany Hall, and could count on a solid white-power South after the end of Reconstruction. But to win nationwide they needed the support of Republican defectors concerned with good government. Cleveland was the perfect candidate to lure them.

His opponent in 1884 was James G. Blaine, a Republican workhorse—congressman, senator, Secretary of State—who had, however, taken a bribe from a railroad earlier in his career. Republican researchers learned that Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child (he had done more than work and eat, it seemed). But a late-breaking anti-Irish screed by a Blaine supporter tipped New York, and the election, to its homeboy.

Cleveland’s run for reelection in 1888 did not go so well. His vice president, Thomas Hendricks, had died in office, so the party gave him for a running-mate Allen Thurman, a 74-year-old congressman so feeble he could not finish speeches he began. Cleveland and Tammany meanwhile quarreled over the New York governorship. The GOP, led by former senator Benjamin Harrison, managed to carry New York by 1,400 votes, out of 1.3 million cast. Despite losing the national popular vote, Harrison won in the Electoral College.

Cleveland bided his time. In his 1892 rematch with Harrison, New York returned to the Democratic column, and Cleveland to the presidency.

How had Cleveland done it? The narrowness of his 1888 loss gave his party hope for a rematch; there was a dearth of viable challengers to the former POTUS. The key to victory was obviously New York, and that reality compelled both Cleveland and Tammany to stop feuding, if not to kiss and make up. Cleveland might better not have bothered. A depression in 1893 destroyed his term and his standing in his own party. Debt-pressed farmers in the South and West embraced populism, which marooned men of his stamp.

Trump counts on beating a Joe Biden enfeebled by age. But Trump himself is no spring chicken, and he has an array of legal issues to contend with. The lure is great, but the path is long and steep.

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.