“Without one hundred of the men for whom Johnny Alison was a prototype, the P-40s might just as well have rusted on the Rangoon docks.” —General Claire Chennault

Sometimes little things make a big difference. But for a quarter-inch, Johnny Alison—Allied fighter ace, pioneer air commando, civil aviation executive and influential U.S. Air Force leader—might have been flying Navy Grumman F4F Wildcats at Midway, not Army Air Corps Curtiss P-40 Warhawks over China. That quarter-inch set Alison on a career path that would make him an Air Force icon, enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame as “a courageous and innovative military strategist,” before his death this year at age 98.

Born in 1912 in central Florida, John Richardson Alison grew up in a Southern culture emphasizing honor, integrity, thrift, hard work and the outdoor life. On his 12th birthday, his father gave him his first shotgun and fishing rod. Thereafter young Alison joined his dad for days of hunting and fishing in the woods, rivers and lakes around Micanopy. Concerned that the three Alison boys get a good education, their parents moved to nearby Gainesville. There, Alison revealed the leadership qualities he displayed years later in the crucible of combat, winning the respect and friendship of his classmates, serving as president of his high school class and, later, as president of his college fraternity.

One day while Alison sat in study hall, Lieutenant Ralph Ruddy, a local boy who had become an Army pilot, returned to Gainesville, buzzing the town in a sleek Curtiss P-1 biplane. After hearing the strident roar of its engine, Alison immediately determined he wanted to become a pilot.

Thereafter, all through high school and during his undergraduate years at the University of Florida (where he studied industrial engineering and was a member of the school’s Army reserve officer training program), he nurtured this dream. But as his interest in flight grew, so too did his parents’ fears for his safety. When he wanted to leave the university after two years to become an Army aviation cadet, they wisely insisted he stay and complete his degree. Hoping he’d discover he disliked being aloft, they let him take a few flying lessons from a local instructor in a Travel Air biplane.

Instead, Alison’s enthusiasm grew stronger still, and his now-alarmed parents forbade further flights. A self-described “obedient child,” he complied—but informed them that, even so, he still wanted to fly. When he graduated they tried one last, desperate ploy, securing him a state government position as a surveyor at $125 a month, $50 more than the monthly salary of a flying cadet, and a tidy sum during the Depression era. But Alison remained firm, refusing the surveying position. Though he had always wanted to be an Army pilot, a year earlier his two closest fraternity brothers had become naval aviation cadets. Now close to receiving their golden wings, they invited him to Pensacola after he finished his degree. The appeal of joining them proved irresistible, and he drove across the Florida Panhandle to the fabled base on the Emerald Coast.

Alison was keen of vision, lean, tough, wiry and athletic. He had played end on his high school football team, captained its swim team and was intramural wrestling champion at the university. He seemingly had every expectation of quick acceptance as a naval aviation cadet. But a ruler-wielding “by-the-book” flight surgeon matter-of-factly informed him that, at 5 feet 5¾ inches, Alison was a quarter-inch too short to be a Navy pilot. Stunned, Alison requested a waiver: no luck. Even after Florida Senator Duncan Fletcher appealed to the Navy on his behalf, the answer was still no.

The Navy’s loss was the Air Corps’ gain: Its minimum height requirement for airmen was 5 feet 4 inches. And so, in the early summer of 1936, young Alison drove to Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Ala., where he passed the physical and took his oath as an aviation cadet. The Air Corps assigned him to a class that had already started preflight training at Randolph Field, so Alison raced to Texas to catch up, arriving (“much to my delight,” he later recalled) too late to experience the hazing that all newly arriving cadets experienced. He later looked back on his year of flight training as “the most pleasant [and] carefree of my life. I really enjoyed it. I loved flying. It was a great thrill, a great exhilaration. It was something that I always wanted to do and I just was not going to fail.”

Randolph, in open land outside San Antonio, was popularly known as the “West Point of the Air.” At the time Alison began his military flight training, the Air Corps was transitioning from the era of the open-cockpit, fabric-covered biplane with fixed landing gear to the era of the streamlined, all-metal monoplane with an enclosed cabin and retractable landing gear. His first forays aloft were in Consolidated PT-3s, progressing to the Douglas BT-2, a big two-place biplane derived from the O-2 observation plane. Both were rugged, forgiving, low-performance aircraft, products of an older and by then obsolete form of design.

The basic training syllabus introduced two new monoplanes, Seversky’s ungainly looking BT-8 and North American’s sleek BT-9. With them, cadets entered a more modern and dangerous world. The Seversky was a close-coupled airplane, prone to violently ground-loop and wind up on its back. The BT-9—predecessor of the famed T-6/SNJ used to train hundreds of thousands of Allied airmen—was seemingly more docile but had its own vice: a vicious stall during tight turns.

The BT-9’s problem was its wingtip design. In a tight turn, airflow would separate from the tip, reducing the wing’s lift. The other wing’s greater lift would then flick-roll the BT-9 over on its back—almost always fatal at low altitude. North American installed automatic leading-edge slats on later BT-9s, curing the problem, but not soon enough for Alison’s class, which experienced at least two accidents from the nasty quirk, one fatal.

During advanced training, students moved to nearby Kelly Field, where they were evaluated before being sent to pursuit (fighter), bomber, attack or observation “tracks.” There they flew aging open-cockpit, twin-engine Keystone biplane bombers, low-wing Curtiss Shrike attack bombers and frisky Boeing P-12 biplanes. (Alison had the base parachute shop make up a 4-inch-thick cushion so he could fly the big Keystone). He excelled in the P-12, which fit its pilot like a glove and earned the affection of all who flew it. Academically first in his class, Alison was sent to the pursuit section. His instructors had such confidence in him that they largely left him on his own while he built solo time and honed his aerobatics. By the time he graduated in June 1937, he had more than 300 flying hours and a perfectionist’s obsession with precision flying.

Now a newly minted second lieutenant with a Regular Army commission, Alison went to the 1st Pursuit Group at Langley Field, Va. He considered it a “wonderful situation,” for the Air Corps was a “very small community where you really got to know people.” His neighbors included a galaxy of future notables such as 1st Lt. Curtis LeMay; Majors Carl Spaatz, Harold George and Caleb Haynes; and Lt. Col. Robert Olds, whose young son Robin, himself destined to become a legendary fighter ace and inspirational leader, roamed the neighborhood.

Langley was a hotbed of Air Corps innovation befitting the times: German, Italian and Russian airmen were already battling over Spain, as were Japanese and Chinese airmen over China. Few in the American aviation community doubted that war would eventually come, and that it would involve the United States. At Langley, airmen flexed the Air Corps’ growing long-range strategic muscle with early service-test Boeing YB-17s. Others, Alison among them, exercised the service’s first modern monoplane fighters.

They evaluated the turbocharged two-seat Consolidated PB-2, Bell’s weird multiplace twin-pusher YFM-1 Airacuda gunship and more practical designs such as the elegant Curtiss P-36 Hawk and its turbocharged inline-engine derivative, the YP-37. Alison had no difficulty intercepting the 2nd Bomb Wing’s much-hyped “Flying Fortresses,” an ominous sign that bomber enthusiasts ignored until Ploesti, Schweinfurt and Regensburg utterly discredited the notion of sending massed formations of unescorted B-17s and B-24s deep into hostile territory.

Like fighter pilots everywhere, Langley’s tested their skills “1 v 1” against each other, learning by doing, and sometimes at a price: One of Alison’s roommates was killed after an ill-considered maneuver triggered a fatal collision. Flying remained a risky business for the Air Corps. Fully 10 percent of Alison’s graduating class perished in their first year of service, and another 10 percent the year afterward. Those who remained developed survival skills that served them well in future years, when the threat came not only from flying but from the enemy—only two of his classmates would die in World War II. The accidents highlighted the importance of realistic training, something Alison would stress when he rose to command, and afterward, when he was vice president of Northrop, manufacturer of the superb T-38 trainer.

Alison stayed at Langley until October 1940, when he was transferred to Mitchel Field, on Long Island, flying the P-40 with the 8th Pursuit Group. In early 1941, having further solidified his reputation as a “golden arm,” Alison received a summons to Washington to demonstrate the P-40 before a Chinese delegation headed by Claire Chennault, a former AAC fighter tactician serving as air adviser to the Chinese government.

Off he flew, south to Bolling Field, nestled at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers, across from downtown D.C. The day was clear and cold, with a bitter late-winter wind gusting off the Potomac and straight down Bolling’s runway. The Air Corps and Curtiss officials at Bolling seemed uncertain how thoroughly Alison should demonstrate the fighter, and the company reps even wondered if their own test pilot should fly it. But Alison had no intention of letting anyone else fill his role.

He strapped in, pointed the P-40 straight into the wind, added throttle and leapt into the air, raising the landing gear and over-boosting the engine. Alison pulled straight into an Immelmann, then slow-rolled the P-40 as he descended to make five tight wings-near-vertical, max-power turns. He rolled out downwind, pointing down the runway, accelerated until he passed over the runway threshold, executed another Immelmann and, now pointed back into the wind, dropped the gear and descended to land, taxiing in, shutting down, unstrapping and dismounting from the fighter as its prop flipped through a last few revolutions to a stop.

It had been an astonishing demonstration by a pilot totally in harmony with his aircraft—and it had lasted less than two minutes. One of the Chinese generals accompanying Chennault broke the stunned silence. Pointing enthusiastically at the P-40, he exclaimed, “We need a hundred of those!” “No, General,” chuckled Chennault, tapping Alison on the chest; “you need a hundred of those.” Soon to lead the American Volunteer Group, the famed “Flying Tigers,” Chennault never forgot Alison’s extraordinary flying display. “Alison was the kind of pilot I needed for the AVG,” Chennault recalled. “Without one hundred of the men for whom Johnny Alison was a prototype, the P-40s might just as well have rusted on the Rangoon docks.”

Ironically, for a man whose combat career is inextricably intertwined with the war in Asia, Alison’s wartime service began in Britain. Short of airplanes, Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted as many U.S. aircraft as he could get, and by mid-August 1940 a British purchasing commission already had 20,000 American airplanes of various kinds on order, as well as 42,000 engines. Among these were P-40 fighters—so many, in fact, that the commission sought a second source of production from North American, leading, eventually, to that firm’s designing the famed NA-73, the progenitor of the P-51 Mustang family.

Shortly after his Chennault demonstration, as Royal Air Force squadrons began transitioning into the P-40, Alison and his friend (and future ace) Hubert “Hub” Zemke went to Britain to advise the RAF on its use and maintenance. Their arrival coincided with the Blitz, and they quickly grew used to the sound of bomb blasts and sirens, as well as negotiating debris-filled streets.

They found that British fighter pilots, having won the Battle of Britain with the elegant Spitfire and plucky Hurricane, regarded the P-40 as just a drab American cousin compared to their own stalwarts. Alison, after flying all three, judged the P-40 better than either the Spitfire or Hurricane at low altitude, and was not afraid to prove it. One RAF Hurricane ace who challenged him soon found Alison locked at his six o’clock, and couldn’t shake him off. He later told Alison he had no idea the P-40 was so good—and hadn’t thought “you Yanks would be as competent as you are.” RAF airmen subsequently took successive models of the Curtiss fighter to the Middle East, where it proved to be an outstanding swing-role low-altitude fighter-bomber over the Western Desert and Italy.

Alison had one close call in Britain when he had to parachute from a Lend-Lease P-40 after its control stick mysteriously jammed during a low-altitude slow roll, fortunately leaving the plane upright, though in a slight dive. With no elevator authority, Alison added engine power to climb, then jumped over open country, escaping with sprained ankles. He enjoyed an impromptu tea with the local Home Guard before the RAF came to fetch him.

More Tales From The CBI

In July 1941, he went to Russia, accompanying President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s emissary Harry Hopkins and other notables to establish the Lend-Lease program with the Stalin government. The next few months brought home the bitterness of the Russo-German war, as Alison witnessed the chaotic evacuation of Moscow, watched the withdrawal of Soviet industry to beyond the Urals and saw train crews dumping the naked bodies of dead prisoners by the side of the tracks, while surviving inmates scavenged their clothes and possessions.

There was much to admire as well, particularly the dedication of Russian airmen and mechanics who worked assiduously to master the P-40 and take it to war. While in Russia Alison learned what had caused his British accident. After a similar incident there, during which he was able to manipulate engine power sufficiently to safely land, mechanics found that Curtiss production line workers had carelessly left numerous bolts and nuts in the fuselage, one of which had worked its way into the control linkage as the plane rolled. An urgent message resulted, ordering Curtiss-Wright to immediately tighten inspection procedures.

In early 1942, Alison relocated to Basra, Iraq, where he supervised the start-up of Lend-Lease delivery of Douglas A-20s and other aircraft to the Soviet Union through Iran. Alison longed to get into combat, however. In July 1942, he at last received orders from Army Air Forces chief General Henry “Hap” Arnold to proceed to China, where Chennault’s AVG had transformed into the 23rd Fighter Group. Upon arriving at Hengyang, he joined the 75th Fighter Squadron, led by Major David “Tex” Hill. The lean and rangy Hill—a former Navy torpedo and dive bomber pilot—was an outstanding airman and combat leader. He and Alison swiftly became good friends.

Frustrated one night at watching Japanese Army Air Force Mitsubishi Ki-21s bombing Hengyang, Alison decided to do something about it. The next night, alerted by Chennault’s excellent warning service of an approaching raid, he scrambled aloft, accompanied by Albert “Ajax” Baumler, a tempestuous veteran of the Spanish Civil War. It is a measure of Alison’s faith that when he closed behind a formation of Ki-21s, his first thought was a prayer: “Lord, forgive me for what I am about to do.” He swiftly shot down two, but not before a Japanese gunner had riddled the P-40’s engine and prop, grazing Alison.

With his engine running rough and the fighter streaming smoke, Alison wisely abandoned the fight. He guided his ailing P-40 earthward, and ditched in a river. The impact threw him into the gunsight, cutting his head and dazing him, but a courageous Chinese youth braved the dark waters to pull him from the cockpit. (Years later, Alison by chance met his rescuer, then an engineer, who had emigrated to America and joined a defense firm run by Northrop.) So great was the need for planes that his battered P-40 was recovered, repaired and returned to service.

While in China, Alison and fellow pilots Baumler, Bruce Holloway, Clinton D. “Casey” Vincent and Gratton “Grant” Mahony—all of whom had test-flown a captured Mitsubishi A6M2—formed the “Zero Club.” Though acknowledging the Zero was a “beautiful flying machine,” Alison still favored the P-40 because of its guns and ruggedness. “When our six .50-caliber guns hit a Japanese airplane,” he recalled, “the airplane came apart.”

Alison left China in May 1943, having shot down six enemy aircraft, flown numerous ground-attack sorties and led the 75th Squadron and the Chinese fighter command in combat. As a commander, he stressed training, flight discipline and competency, concentrating on ensuring that new pilots joining the squadron (many with only 200 hours aloft) were given adequate training and experience before going into combat. In his concern for training and teamwork he was very much like Germany’s Oswald Boelcke, Britain’s Edward “Mick” Mannock or America’s Raoul Lufbery, and he anticipated jet age fighter leaders who followed him such as Robin Olds and Richard “Moody” Suter.

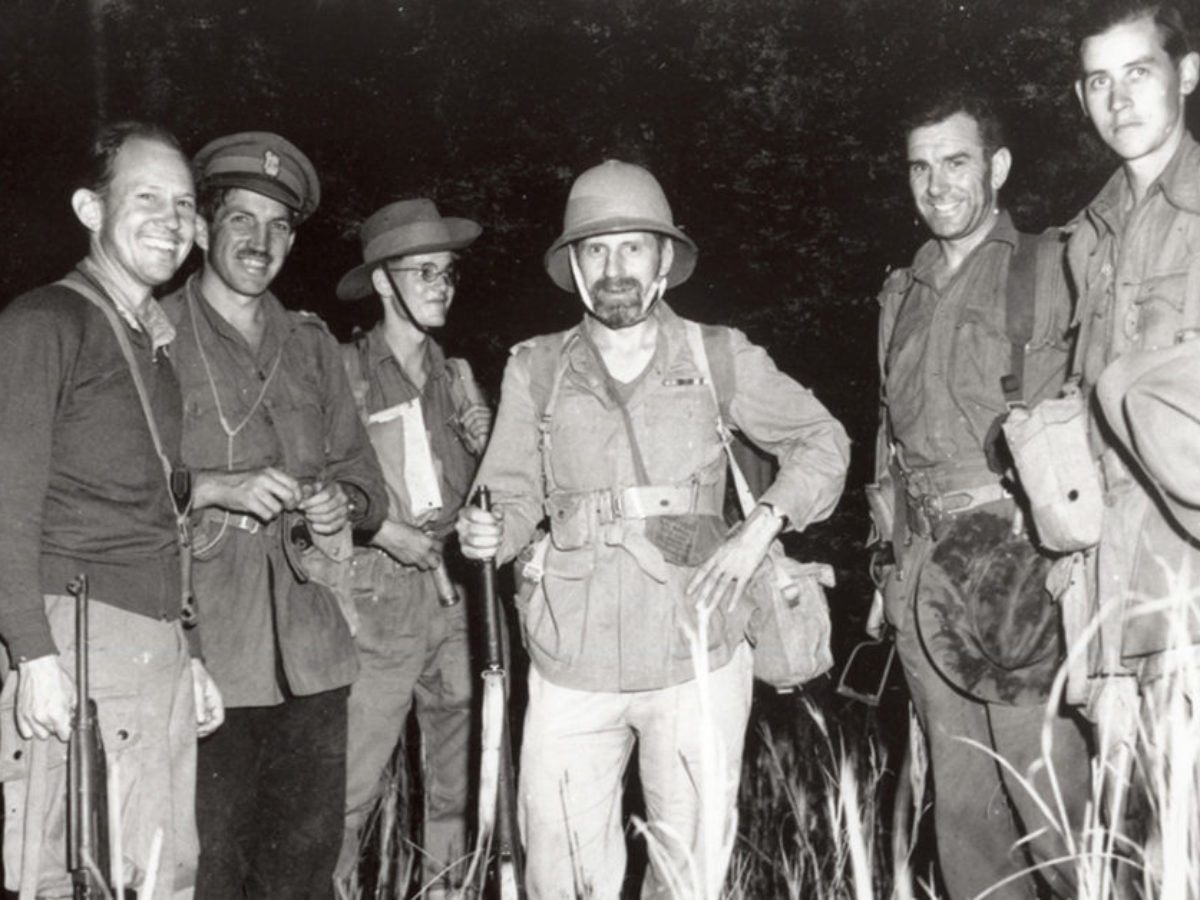

Arguably Alison’s greatest contribution to the Allied war effort was partnering with Colonel Philip Cochran, one of his old Langley roommates, in establishing and leading an elite force in a week-long air assault deep behind Japanese lines in Burma, dubbed Operation Thursday. In 1943 Brigadier Orde Wingate, a charismatic and unconventional British combat leader, was waging a grim guerrilla war in Burma. His commandos, called “Chindits” after the Chinthe, a mythic temple guardian spirit, needed air support, mobility and casualty evacuation. Hap Arnold picked Cochran and Alison for the effort, appointed them co-commanders and ordered them to circumvent any and all bureaucratic obstacles, exclaiming, “To hell with the paperwork, go out and fight!”

They did. First, Alison, always more concerned with accomplishing the mission than personal glory, told Cochran with characteristic modesty that in the interest of a clear chain of command, he’d serve as Cochran’s deputy. Then the two put together a powerful air expeditionary force, the 5318th Provisional Air Unit: 30 P-51A Mustangs, 12 75mm-cannon-armed B-25H Mitchells, 13 C-47 transports, 150 Waco CG-4A gliders, 12 UC-64 Norseman light transports, a mix of L-1 and L-5 light aircraft for medevac and six of Sikorsky’s new YR-4 helicopters. Altogether, it numbered 348 aircraft.

On the night of March 5, 1944, Alison piloted a CG-4A into Broadway, one of two jungle landing sites, an experience he later compared to “going through hell a second at a time.” The flight and landing were extraordinarily hazardous; most of the 40 gliders that flew into Broadway that night cracked up, and 28 airmen and Chindits perished. Alison soon supervised preparation of a landing strip for the larger C-47s, which brought in heavy equipment to clear an even larger landing area. It was risky work, for gliders were still landing, and, as he recalled, “You had to be mighty quick to get out of the way.” Afterward Brigadier “Mad Mike” Calvert, one of Wingate’s Chindit commanders, complimented Alison for doing “a wonderful job in appalling circumstances.” Altogether the Thursday landings inserted more than 9,000 troops, 175 horses, 1,283 mules and over 250 tons of supplies. Supported by the strike and transport aircraft of the Air Commandos, the Chindits subsequently savaged Japanese forces before withdrawing.

For his contributions to the success of Operation Thursday, Alison was awarded the Legion of Merit. The 5318th would become the 1st Air Commando, a combat force that has evolved over time into today’s globe-ranging Air Force Special Operations Forces.

Following his success at Broadway, Alison briefed General Dwight Eisenhower, then overseeing final preparations for the Normandy invasion, on the practicalities of using gliders for night assault. He returned to the States, where Hap Arnold had him supervise the formation of two more Air Commando units. He then deployed to the Pacific as operations officer for the Fifth Air Force under Maj. Gen. Ennis Whitehead, participating in the landings in the Philippines, during which he narrowly escaped a flaming kamikaze that struck the bridge of the battleship New Mexico, killing 30 (including its captain) and wounding 87.

Having begun the war as a first lieutenant, Johnny Alison finished it a colonel, with the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Silver Star, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, Air Medal and British Distinguished Service Order to his credit. He resigned from the AAF in 1947, but returned to government service as assistant secretary of commerce, advocating development of new aircraft to meet the challenge of postwar air transport. He joined the Air Force Reserve during the Korean War, and was promoted to major general before retiring in 1955. Afterward he became an international businessman, then a senior vice president with Northrop, serving that company until 1984, during which time Northrop developed the T-38 and F-5, the F-20, the YF-17, the Tacit Blue stealth demonstrator and designed the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

Still, he kept his eyes on the future. “He was sharp as a tack, and captivated by advanced propulsion,” recalled Mark Lewis, former chief scientist of the U.S. Air Force. “At age 95, he was still exploring various ideas and their implications for future aerospace vehicles.”

Major General John Alison died on June 6, 2011, mourned by those who knew him as a great man as well as a consummate airman—one who had loved his country with a deep and abiding passion and who always placed others ahead of himself. “Dedication to the Air Force was ingrained in his being,” his friend Douglas Birkey recalled. “During his last days he still wanted to discuss the future of the Air Force. An amazing individual.” Amazing indeed.

Richard P. Hallion is a former U.S. Air Force historian and the author of numerous works on aviation history. For further reading, he recommends: Operation Thursday: Birth of the Air Commandos, by Herbert Mason and Sergeant Randy G. Bergeron; Way of the Fighter: The Memoirs of Claire Lee Chennault, by General Claire Lee Chennault, with Robert Hotz, ed.; Back to Mandalay, by Lowell Thomas; and Global Mission, by General Henry H. Arnold.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2011 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!