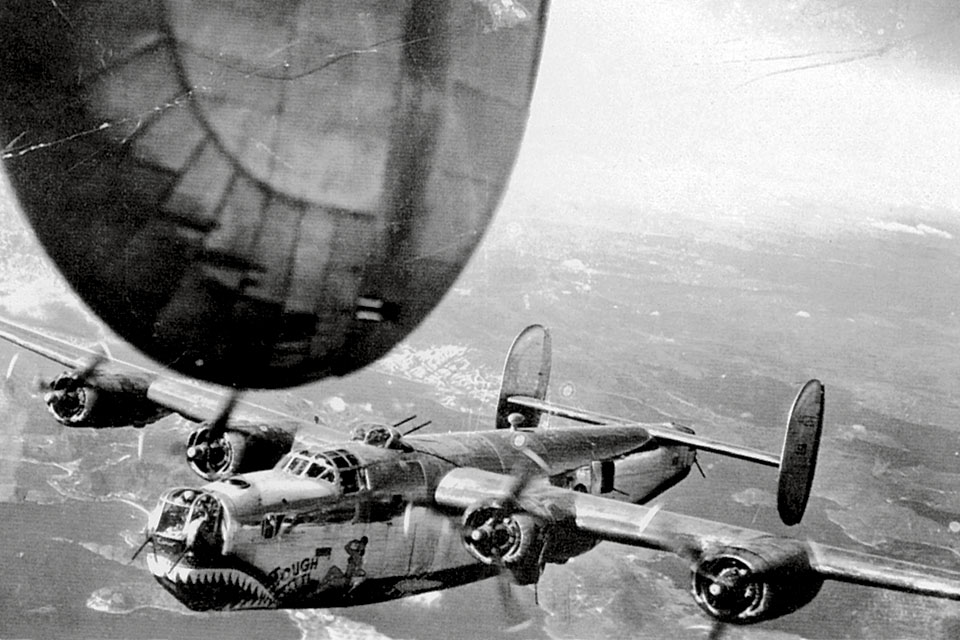

After almost six months of continuous combat duty in China with the Fourteenth Air Force, Sergeant Hobart Jones, the nose-gunner and engineer of a Consolidated B-24J named Tough Titti, was no stranger to surprises. One experience he later vividly recalled happened in midsummer 1944, while he and his unit, the 375th Bomb Squadron, 308th Bomb Group, were leaving the target area, 18,000 feet over Nanking.

“We’d just assembled into a tight defensive formation with maybe 100 feet separating our planes,” Jones said. “And several thousand feet over our heads, our escorts—a mix of P-40s and P-51s—were in the middle of a dogfight with a bunch of Jap fighters. I happened to be looking over to my left when this Jap fighter—I believe it was an Oscar [Nakajima Ki.43]—just seemed to drop out of nowhere and form up right behind our left wing.” Jones threw up his hands and mimicked the shock that had been on his face at the time. “I thought I was hallucinating!” he declared with a laugh. “The Jap pilot and I were staring at each across a space of maybe 50 feet, maybe less. The guy had on a fur-trimmed helmet and sported a bushy mustache, and he was grinning—grinning at me! Nobody could take a shot at him because our planes were in each other’s line of fire. After what must have been only two or three seconds of looking at this guy, my headset erupted with the voice of my pilot screaming, ‘Step up! Step up!’ He was calling the plane next to us, telling them to move so we could get a clear shot. But the exact instant the other ship moved, the Jap flicked over on his back and split-essed right out of there—I mean, got clean away without one shot being fired!”

In a one-year odyssey, Jones had left his family farm in Shady Grove, Ark., enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), trained all over the United States and arrived in China in February 1944 as a buck sergeant. “In the States, we’d all [B-24 crews] been trained strictly for high-altitude, daylight precision bombing,” Jones said, “but that turned out to have little bearing on what they did with us in China. After we got there, we were required to fly whatever kind of mission the military situation called for from day to day. It wasn’t unusual,” he explained, “for us to fly a long mission to Hong Kong—a 1,400-mile round trip from our base at Chengkung [near Kunming]—where we’d be dropping bombs on the docks from 20,000 feet; then, a day later, get ordered to make a low-level bomb run on a bridge or a railroad tunnel.” To Jones, “low” meant as near to the ground as they could get and still clear obstacles, at times down to 50 feet above the ground. “Sometimes we’d go right down on the deck and strafe,” he said, “to shoot up the Jap supply boats on the rivers or maybe a train if we caught one.”

Jones recalled that the 375th’s most persistent problem wasn’t combat requirements but supplies: “Our B-24 outfits normally had to fly three to five resupply trips to India and back just to get everything we needed—gas, bombs, ammunition and so on—to mount one combat sortie. Of course that meant flying ‘the Hump,’ a three-and-a-half-hour trip each way, and most of the time we did it in overloaded airplanes. [The Hump was the name American aircrews had attached to the Himalayan mountain range.] And the shortage of parts made it impossible to keep a lot of the B-24s in service. The biggest number of planes I ever saw the 308th put in the air at one time was 28, and that was only once.”

During World War II, the China-based Fourteenth Air Force was not only the most short-lived of the numbered air forces, existing for a period of less than 34 months (March 5, 1943 to December 31, 1945), it was the smallest to operate in a combat theater, reaching a peak strength of just six air groups and four auxiliary squadrons (approximately 700 airplanes) by the end of 1944. It holds the singular distinction of being the only numbered air force to have been wholly created, organized and operated within a war zone. Despite its limitations, the Fourteenth went on to produce a truly astounding war record: 2,908 enemy aircraft destroyed or damaged against 193 combat-related losses of its own; 2.1 million tons of shipping sunk or damaged; 99 warships sunk or destroyed; an estimated 18,000 small rivercraft (carrying enemy troops and supplies) destroyed; and 1,225 locomotives, 817 bridges and 4,836 trucks destroyed. Added to that were approximately 59,500 Japanese troops killed in close air support engagements.

For most of its life the Fourteenth Air Force was commanded by one of the most controversial USAAF leaders of the wartime period, Maj. Gen. Claire Lee Chennault. The ultimate success of the Fourteenth did little or nothing to relieve the longstanding estrangement between Chennault and his superiors at the Pentagon. When the Japanese threat in China had been neutralized, he was relieved of command. On September 2, 1945, during the surrender ceremony aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, five-star Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur was reported to have asked, “Where’s Chennault?” He had not been invited.

Unlike the other air forces created during World War II, the Fourteenth was not the typical, planned-from-the-top military organization; in fact, the U.S. military leadership, from the Joint Chiefs of Staff on down, was unanimously opposed to the idea of establishing a separate numbered air force in China. All of them believed that such a venture would be a tactical and logistical rat hole down which money, materiel and manpower needed elsewhere would be wasted. Yet, even before the United States entered the war, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was anxious to make some gesture to assist the beleaguered Chinese. Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalist government had been embroiled in a war with Japan since 1937 and had repeatedly begged the United States for help. So in April 1941, against the advice of his military staff, Roosevelt authorized the Chinese to recruit pilots and ground crewmen from the U.S. military services for a “civilian” fighter unit to be called the American Volunteer Group (AVG). He also allowed the Chinese government, through a civilian cover organization, to purchase 100 Curtiss Hawk 81A-3 fighters (export models of the P-40C) that had been earmarked for Britain’s Royal Air Force.

The man selected by Chiang to organize, train and lead this force was ex-U.S. Army Air Corps captain Claire Lee Chennault, who since 1937 had functioned as Chiang’s chief adviser on military aviation matters. Though classified as an eccentric by his former Air Corps peers, Chennault had nonetheless spent his time well in China, not only learning to effectively deal with his Chinese hosts but also becoming an expert on Japanese tactics and capabilities.

The earliest mission of the AVG, which became famous as the “Flying Tigers,” was to protect the vital rail-, road- and sea-based supply routes between China and Burma. Despite noteworthy tactical successes (the AVG was ultimately credited with the destruction of 286 Japanese aircraft against a loss of 14 of its own pilots), Chennault’s small fighter band was unable to reverse the overwhelming tide of invading Japanese forces, and the Burma supply routes were completely sealed off in early March 1942. China was effectively severed from surface contact with the rest of the world, and the only means of resupply was by air via India—over the Himalayas, the highest mountain range in the world.

When the civilian AVG was disbanded on July 4, 1942, it was incorporated into the China Air Task Force (CATF), a subcommand of the AAF’s India-based Tenth Air Force. Claire Chennault was recalled to active duty in the AAF at the rank of brigadier general and placed in overall command of the CATF. Starting with one fighter group consisting of 51 P-40s inherited from the AVG, the CATF was soon augmented by North American B-25s of the 11th Bomb Squadron and tasked with the broad responsibilities of interdicting enemy movements, protecting the southern and eastern approaches across the Himalayan Mountains, and defending the China terminals and bases.

The CATF’s combat tactics were characterized by mobility and surprise, attacking enemy supply lines, dock facilities, military installations and airfields across a 1,000-mile battle front while simultaneously being prepared to take off and intercept incoming Japanese aircraft that had been sighted by the Jing-Bao warning net. Originated by the AVG, the term Jing-bao meant “to be alert,” and became the name for a system of observers scattered throughout the China front who reported enemy aircraft movements using a combination of radio and semaphore signals. By way of this system, CATF fighters were regularly able to intercept Japanese aircraft long before they reached their targets. And as the CATF planes were moved from one forward base to the next, their spinners and markings were often repainted to mislead Japanese observers. The tactics and the warning net were effective enough to cause Japanese intelligence analysts to grossly overestimate American air strength in China through the balance of 1942; they believed the CATF was operating a force of at least 200 planes when, in fact, there were no more than 30 operational at any one time.

As new combat units arrived in late 1942 and early 1943 to boost CATF numbers, the stress on the supply system intensified. The recently constituted India-China Division of Air Transport Command (ATC) was unable to keep up with the combined demands of the Chinese army, U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater and the CATF, a problem made worse because nearly all the CATF bases were at the ends of the supply lines. Priorities on materials were set by Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, the U.S. theater commander in China, and Maj. Gen. Clayton L. Bissell, Tenth Air Force commander, to which the CATF was technically subordinate. The situation was further aggravated by Chennault’s habit of consulting directly with Chiang Kai-shek or the White House and ignoring the normal chain of command, a practice greatly resented by Stilwell and Bissell.

Out of this fractious command relationship the CATF was reconstituted as the Fourteenth Air Force on March 5, 1943, with its headquarters in Kunming. Although Roosevelt was generally not in the habit of interfering with the prerogatives of military leadership, in this instance he created a wholly new numbered air force by presidential order. As part of the same order, Chennault was promoted to the rank of major general and given command of the new organization. In contrast to the military chain of command (Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall termed Chennault “disloyal,” Chief of the AAF Henry H. Arnold rated him a “crackpot,” and Stilwell referred to him as a “jackass”), Roosevelt admired the feisty Chennault, whom he had met in 1941. But perhaps more important, he knew that Chiang Kai-shek would have been angered by the appointment of anyone else.

Although the Fourteenth had been elevated to the status of a theater-level air force, its mission remained essentially guerrilla in nature: to disrupt, harass and confuse the movements of a numerically superior enemy. According to several references, Fourteenth Air Force headquarters perceived itself as responsible for the following military objectives: (1) defend the Allied supply lines over the Himalayas; (2) seek and destroy enemy aircraft and troop concentrations; (3) destroy enemy military and naval installations; (4) interdict and destroy enemy shipping along China’s coastline and inland waterways; (5) interdict and destroy enemy supply lines within China, Indochina, Thailand, Burma and Formosa; (6) provide close air support to Chinese ground forces; and (7) encourage the Chinese resistance to assist AAF airmen in enemy-occupied territories. In short, they were to stall Japanese forces as long as possible, not defeat them. It would ultimately be the job of Chiang Kai-shek’s armies to repel the Japanese, but in early 1943 Chiang’s poorly trained and ill-equipped forces could scarcely defend the territory they already held.

Chennault recommenced combat operations as the Fourteenth Air Force with an arsenal of about 170 aircraft, mostly obsolete P-40s, one reconnaissance squadron of Lockheed F-5s (photoreconnaissance version of the P-38) and one squadron of B-25s; however, lack of logistical support caused the B-25s to be grounded for much of early 1943. Opposing the American airmen at that time was a force of approximately 450 aircraft belonging to Japanese army and navy units. The Fourteenth’s numbers were bolstered in May by the arrival of B-24s of the 308th Bomb Group (Heavy), which had the effect of greatly extending the command’s radius of attack, especially to the faraway centers of Japanese shipping and supply, and, as described by Hobart Jones, the B-24s possessed the added advantage of being logistically self-supporting.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1943, the Fourteenth’s two P-40–equipped fighter groups, the 23rd and 51st, were called on to perform a variety of tasks: protection of AAF and Chinese bases from enemy air attacks; fighter sweeps near Japanese bases that were designed to lure enemy fighters into action; fighter-bomber interdiction of Japanese supply routes, particularly along the Burma Road in the southeast; and escorting the B-24s and B-25s on bombing raids against major enemy military and supply installations. When scrambled via the Jing-Bao warning net, there were sometimes only two or three P-40s available to oppose formations of 30 to 40 Japanese bomber and fighter aircraft, but such measures were often sufficiently disruptive to cause the bombs to miss their intended targets.

The Chinese-American Composite Wing (CACW) became a part of the Fourteenth Air Force in July 1943. The CACW consisted of Chinese aircraft and crews trained under Lend-Lease with a combination of Chinese and USAAF officers serving as the wing’s group, squadron and flight leaders. Organized as two fighter groups of P-40s and one bomber group of B-25s, CACW units began their first combat operations in October 1943. The coming in of the CACW effectively gave Chennault command and control over all tactical aviation operations occurring within the China theater.

As increasing numbers of aircraft and aircrews enabled the Fourteenth to expand its reach, the command was split into two composite wings in December 1943, roughly dividing operations between east and west China along the 108th meridian. The 69th Wing, commanded by Colonel John Kennedy, was headquartered in Kunming and assumed responsibility for an area that extended west to Burma and included the Hump supply lines; the 68th Wing, commanded by Colonel Casey Vincent, which operated as more of a frontal unit, was given the responsibility for an area that extended from Shanghai to Indochina and also included the shipping lanes in the South China Sea and the Formosa Strait (today known as the Taiwan Strait). Sustaining the 68th’s widespread combat operations would ultimately prove problematic because of the great distances from normal supply lines, with the result that its aircraft were sometimes grounded for lack of fuel.

Starting the new year with 285 aircraft on hand, Fourteenth Air Force operations in the early months of 1944 were characterized by a lull in activity by Japanese ground forces in China and poor weather conditions. The fighters, whose ranks were now augmented by P-38s of the 449th Fighter Squadron and a handful of North American P-51s to replace the aging P-40s, continued to fly sweeps and fighter-bomber strikes, while the B-25s simultaneously concentrated on river and sea sweeps along the Yangtze River and South China Sea. Heavy bombardment operations were delayed in the first four months of the year due to fuel shortages. During the same period, however, Japanese forces in China had been building up to mount an offensive aimed at opening a north–south corridor from Hankow all the way to Indochina. Such a move would not only create overland rail routes between their territories, but would also eliminate many of the forward bases from which the Fourteenth was flying antishipping strikes. The Japanese offensive, a three-pronged attack involving a force of 250,000 men, began on April 17, 1944, and continued off and on through the remainder of the year, eventually pushing the Chinese lines another 200 miles inland from Chengchow to Indochina and causing the Fourteenth to lose 13 of its bases in eastern China. Even with the loss of valuable bases, the Fourteenth was not deterred by the Japanese onslaught. With two new groups of Republic P-47s and two more squadrons of B-25s joining it in the spring and early summer of 1944, the Fourteenth began a series of intensive interdiction strikes along the newly established north–south Japanese corridor. Chief among the targets were the railways—bridges, tunnels, locomotives and marshaling yards. At the same time, the B-24s of the 308th Bomb Group stepped up their attacks on Japanese shipping in the sea lanes and the rivers, which included laying mines, and fighter units flew hundreds of sorties in support of the Chinese army all over the huge frontal area. During the time the Japanese offensive in China was in full swing, Boeing B-29s of the XX Bomber Command began arriving in the CBI for eventual deployment from bases located in the Chengdu area of central China. Taking their orders directly from the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, however, the B-29s were officially attached to the Twentieth Air Force and in no way connected to tactical operations within China itself but intended for strategic attacks on the Japanese Home Islands. Chennault’s repeated demands to use the Superforts against the Japanese armies in China only served to widen the chasm between himself and the Joint Chiefs. The B-29s were ultimately withdrawn from the CBI in early 1945 and moved to the Mariana Islands. In spite of Japan’s 1944 offensive, the India-China Division of the ATC continued to increase the tonnage of supplies being delivered across the Hump, which in turn permitted the Fourteenth to further expand its operations. All through the fall and winter of 1944, new Merlin-equipped P-51s began to arrive in China to form the new 311th Fighter Group and also replace many of the war-weary P-40s operating in other groups. During this period, other new aircraft and crews were added to the Fourteenth’s roster, such as two squadrons of troop-carrying Douglas C-47s and the 426th Night Fighter Squadron, equipped with Northrop P-61 Black Widows. Before year’s end, the command’s inventory had risen to a force of 700 aircraft versus an estimated Japanese force of 1,200 planes—still outnumbered but in far better shape than the year before.

The new year—1945—turned out to be a time of major transformation for the Fourteenth Air Force. Its determined interdiction efforts during the enemy offensive had borne fruit: The Japanese advance was permanently stalled, and counterattacking Chinese forces, supported by the Fourteenth and the CACW, were starting to regain territory. Equally as important, the Allies, after a yearlong push, had regained enough of Burma by February 1945 to reopen the overland supply routes from India. The Fourteenth was now positioned to become the conventional striking force envisioned by Chennault—one that would eventually thrust at the Japanese mainland.

But the reopening of the supply lines brought about sweeping changes in the CBI. The CACW was abolished, and the Fourteenth and Tenth air forces were placed under a unified command, the China Theater Air Forces (CTAF). While Chennault might have seemed the most logical choice to lead the new command, it was given instead to Lt. Gen. George Stratemeyer.

Following FDR’s death, Generals Marshall and Arnold made plans to limit Chennault’s role by giving him a job in one of CTAF subcommands. It probably surprised no one when Chennault refused. On July 8, 1945, Maj. Gen. Claire Lee Chennault retired for the second time. Plans to use the CTAF in support of the invasion of Japan never materialized, and what had once been the Fourteenth Air Force disappeared from China by the end of 1945.

E.R. Johnson is a frequent contributor to Aviation History. Additional reading: Kenneth C. Rust and Stephen Muth’s Fourteenth Air Force Story in World War II; and Malcolm Rosholt’s Days of the Ching Pao: Photographic Record of the Flying Tigers—14th Air Force in China in World War II.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2005 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!