The surging mass of armed men stopped the train full of Union recruits and herded the passengers out of their cars. The bold move occurred in Pennsylvania, sending shock waves across the Keystone State. Governor Andrew Curtin dashed off a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton alerting him of the “formidable” hostile presence in his state. But Curtin wasn’t concerned about Confederate troops during the Gettysburg Campaign; it was October 1862 and he was fretting about one of the first concerted efforts by Northerners to oppose the Union’s war effort during the war, a series of riots that took place on the western edge of Schuylkill County in Pennsylvania’s turbulent coal region. These small-scale riots lasting less than a week proved to be a harbinger of much bloodier, more violent uprisings against the draft in 1863.

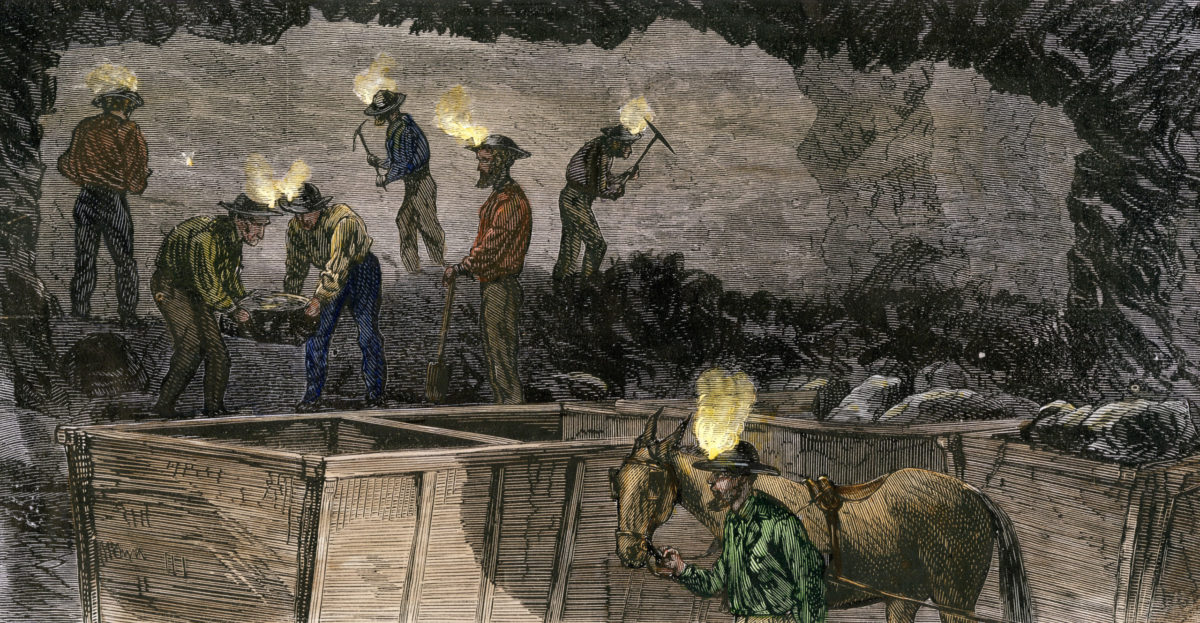

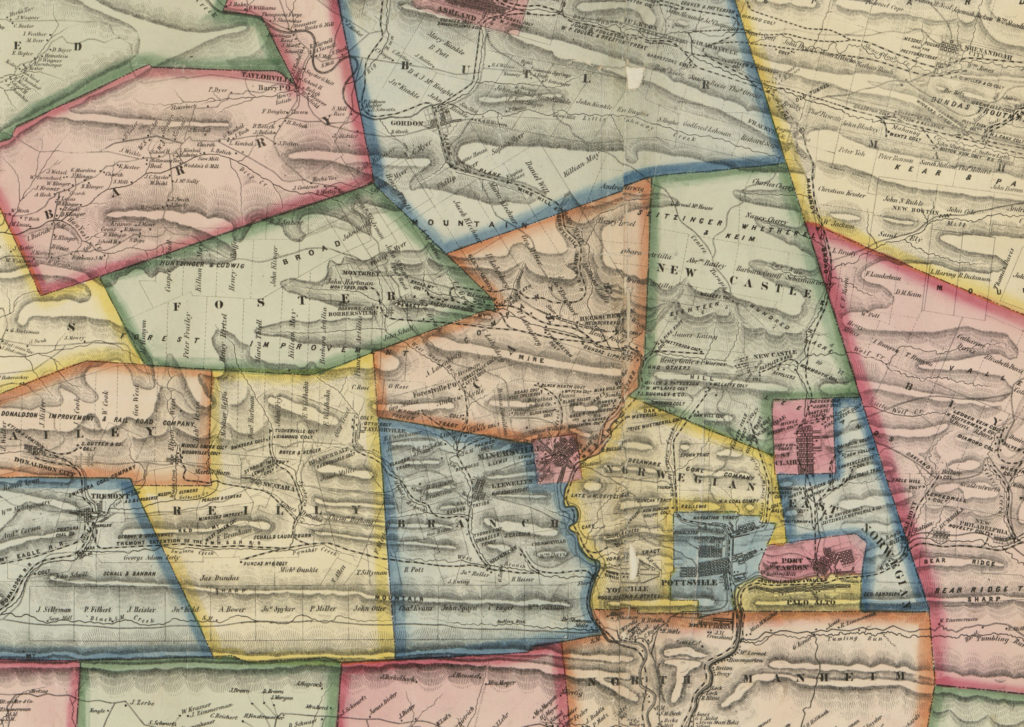

In late October 1862, Irish mineworkers from the county’s mining districts took up arms against the state and federal government and the prospect of a draft to fill the ranks of a U.S. Army depleted by bloody campaigns in the summer of 1862. Resistance to the war effort came most strongly from Cass Township, a community northwest of Minersville in Schuylkill County. The township had been named for Lewis Cass, the 1848 Democratic nominee for president, and the district, which supported a number of the county’s most prosperous anthracite coal mines, raged with zeal for radical Democratic politics. These beliefs led residents in the region to support anti-war, anti-abolition stances that would later be associated with a poisonous snake by political opponents—Copperheads. In October 1862, these ideals were inflamed further by a hard-fought congressional election campaign in addition to the fears of a draft.

“The threat of imminent conscription and the heated election campaign exacerbated long-standing class, ethnic, and political tensions in Cass and the surrounding coal regions,” writes historian Grace Palladino in her book, Another Civil War: Labor, Capital, and the State in the Anthracite Regions of Pennsylvania, 1840-1868. These tensions came to a head in a showdown between miners and the federal government in the autumn of 1862.

“The riot disease seems chronic in Cass Township,” wrote the Miners’ Journal of Pottsville, in a review of events published on October 25, 1862. “The people of Cass became excited and early this week, went colliery to colliery, stopping the operations, compelling the men to join them, until they mustered together several hundred armed men.”

With work in the collieries north of Minersville at a standstill, these miners began a campaign to stanch efforts by the state government to muster troops from Schuylkill County. The workers organized themselves and prepared to consolidate their efforts across western Schuylkill County.

“The head-quarters of the disaffected appear to be at Hecksherville,” recorded a correspondent familiar with events in Schuylkill County. On October 22, Bishop James F. Wood of the Philadelphia Archdiocese arrived in Pottsville to utilize Catholic political sway in the Irish districts to quell riotous behavior. His arrival ultimately helped play a role in easing the tensions in coal regions, but not before significant escalation by mineworkers in Cass Township.

In Hecksherville, organizers appeared to enact a multi-prong strategy for their protest. Representatives were sent to neighboring districts in order to stop work and add to the numbers of armed men. Others were sent west toward the mining village of Tremont in order to stop trains filled with recruits for the Union Army. These men would also act as reconnaissance for the movement. “Miners stationed boys along the railroad lines to give notice of the approach of any troops,” wrote the correspondent in The Philadelphia Inquirer.

In Tremont, the rebellious miners were successful in their initial efforts. “At Tremont, some 500 of them, well armed, stopped a train as it was leaving,” wrote the editors of the Miners’ Journal. “They ordered the [recruits] to get out, and said that those who wanted to go, could; but that those who did not want to go might remain, and that [the miners] might protect them.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Miners from Cass Township and neighboring New Castle Township also sought to raise miners from the neighboring regions to join their cause. “On Friday evening [October 24] a committee went to Ashland from the lower part of the county and made an attempt to swear the miners not to labor on Saturday,” recorded the Inquirer. “The effort was not successful.”

In addition to the setback at Ashland, events took a sad turn at New Castle Township when an armed miner accidentally discharged his rifle and killed another miner. A writer blamed either “the excitement of the moment or the influence of strong drink” for the shooting.

Leaders Respond

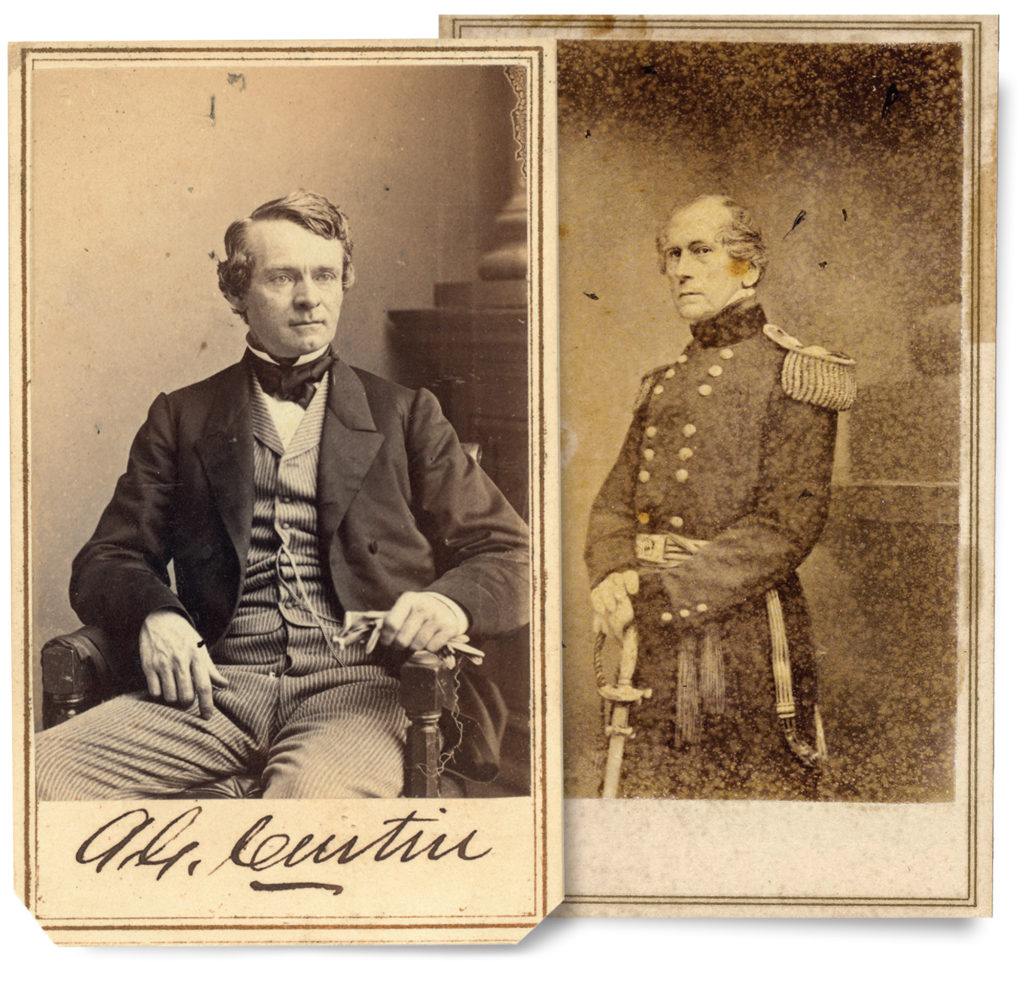

It was the bold act at Tremont that raised alarms in Harrisburg, the state capital. Governor Curtin learned of events in western Schuylkill County on October 23. He dashed off a quick telegram to Secretary of War Stanton in Washington, D.C., that afternoon:

“Notwithstanding the usual exaggerations, I think the organization to resist the draft in Schuylkill, Luzerne, and Carbon counties is very formidable. There are several thousands in arms, and the people who will not join have been driven from the county. They will not permit the drafted men, who are willing, to leave, and yesterday forced them to get out of the cars. I wish to crush the resistance so effectually that the like will not occur again. One thousand regulars would be most efficient, and I suggest that one be ordered from the army….

“Let me hear immediately.”

Stanton responded affirmatively, stating that Curtin could use Federal troops to quell the riots in the coal region. Getting those soldiers, however, was a different matter. Referrals for troops from Maj. Gen. John Wool in Baltimore initially came back negatively, for he had none to spare.

A flurry of cables flashed between Harrisburg and Washington from October 23-25 as the situation developed in Schuylkill County. Curtin’s urgent pleas for troops finally pushed the secretary to take action. “The General Government will exert all means at its command to support you,” he wrote. But he could not send the 1,000 U.S. Army Regulars asked for by the Keystone State’s chief executive. Instead, he promised the services of the Anderson Cavalry and an additional regiment with some combat experience.

Wool arrived in Harrisburg on October 24. He cabled Washington with his plans to assist the governor in putting down the rebellion in the coal region. “I have ordered a section of artillery to report to [Curtin] without delay, with ammunition,” he wrote, “and put an infantry regiment of Pennsylvania volunteers, now on the Northern Central Railroad, subject to his call at any moment.”

According to Representative Alexander K. McClure, an infantry regiment arrived in Pottsville to put down the riots north and west of the city. No orders were given to these troops, however, and they held fast in the Schuylkill County seat. The Philadelphia Inquirer pegged this on the advantages held by those in the mining districts. “It would have been utterly impossible, under any circumstances, for soldiers to have either captured or conquered the men who were so well informed of the secrets of every mountain pass and valley,” their correspondent wrote.

By the 24th, the rebellion in the coal region had begun to abate. The actions of Bishop Wood of Philadelphia played a major role according to those on the scene. He called together religious leaders from across Schuylkill County and encouraged them to talk down the riotous miners and bring them back from the brink of violence. In Tremont, the Inquirer reported, a local priest explained “the necessity of preserving the Union and enforcing the Laws.”

He went in the midst of the crowd and illustrated some of his remarks in such a forcible manner that one or two of the would-be rioters, who were disposed to be insolent, were overawed….[T]he clergy received instruction to preach on Sunday upon the evils of resisting the constituted authorities of the land, and it was understood that the threat of excommunication was to be used against those who were still determined to be troublesome.

Observers felt that winning the Catholic leadership to the side of the government in this matter proved tremendously successful and calmed tensions in Cass Township and surrounding communities. By October 25, the drama in western Schuylkill County drew to a close. “The riots in Schuylkill County have ceased for the present,” Curtin cabled Washington that afternoon. In a note telegraphed on October 27, he confirmed the end of the rebellion and thanked Bishop Wood, “who kindly went up [from Philadelphia] when requested, and relieved us all.”

Continued Unrest

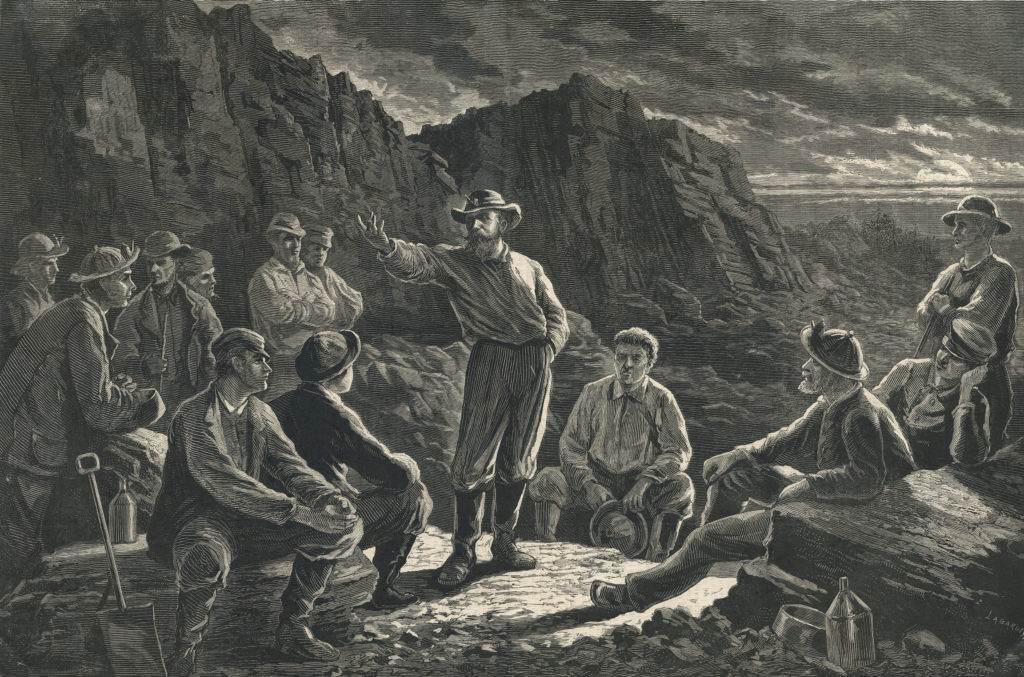

The anti-conscription activities of miners in Schuylkill County ceased for the moment, but this was far from the last violence in the southern coal region. McClure saw the rebellion in a wider context when he looked back while writing a memoir of his time in Pennsylvania politics in 1905. “In several of the mining districts there were positive indications of revolutionary disloyalty,” he wrote, “and it was especially manifested in Schuylkill, where the Molly Maguires were then in the zenith of their power.”

In the coal region, the subsequent decade saw continued unrest, with blame placed on the so-called “Molly Maguires.” This alleged band of Irish conspirators were blamed for violence throughout the anthracite coal fields into the 1870s. Whether or not an organized group actually existed continues to be hotly debated today. However, what is indisputable is that violence in the coal fields surged starting in October 1862 and continued in the decade that followed.

The 1862 unrest shares similarities with other outbreaks of anti-conscription violence that occurred in the North during the Civil War.

The most famous of those outbreaks came in July 1863 in New York City, when draft riots by working class immigrants leveled significant portions of the city, caused millions of dollars in destruction, and resulted in the deaths of more than 100 people in America’s largest city.

In the coal region, Republicans blamed Democratic politicians for the violence in October 1862. “The men who are really responsible for these troubles are the leaders in this Region, of the Sham Democracy,” opined the Miners’ Journal, “and we shall never be free from difficulty until these men lose their influence for mischief, over the mass of our workingmen.”

But racial and ethnic undertones were also present. The Gettysburg Compiler, a Democratic newspaper in Adams County, copied a note from a similarly minded Schuylkill County press in November 1862 under the headline “CONTRABANDS TO BE SENT TO THE COAL REGIONS.”

“We can tell the President of the United States, and his Abolition advisers, that they must keep their Negroes out of the coal regions, unless they desire to inaugurate civil war in the North.

“The people of this section of the State will not allow emancipated slaves to be thrown into competition with white labor.

“The statements that there is a scarcity of workman in the coal mines of Pennsylvania has no foundation in truth so far as Schuylkill County is concerned, and has only been gotten up by the Abolitionists to cover their design to supplant white labor by the employment of negroes…

“President Lincoln must keep his pet lambs out of Schuylkill County.”

This conspiracy theory buried itself deeply in the working-class Irish community in Schuylkill County. The Philadelphia Inquirer, in its article on the violence in western Schuylkill in October 1862, cited this fear among the region’s Irish miners. “Upon some of the more ignorant miners,” their correspondent wrote, “the rumor of the introduction of negro labor into the region has had bad effect.” He described the story as having “general currency” in Cass Township and neighboring communities.

The outbreak of rebellion in Schuylkill County in October 1862 developed from numerous threads of discontent in the laboring classes of the coal region. Resentment about conscription, the Civil War, and emancipation fed into traditional channels of Democratic resistance to the conflict. Historian Grace Palladino points to labor struggles and labor organization as also having significance in the outbreak of this minor rebellion. A toxic combination of class warfare, racial and ethnic fear, and the increasingly unpopular war all led to the violent outbursts in the coal region in 1862.

Jake Wynn is the former Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He writes at wynninghistory.com. He currently lives in Frederick, Md.