THE U.S. SENATE Labor and Education Committee began its day on April 2, 1946, with a thunderous exchange between pillars of that body over the legislation under discussion.

“It is to my mind the most socialistic measure that this Congress has ever had before it, seriously,” Senator Robert A. Taft (R-Ohio) declared.

With equal vehemence, Senator James E. Murray (D-Montana), replied, “Everything that has been attempted to be done for the welfare of the American people has men like you coming along charging it with being communistic.”

Taft persisted in decrying the measure as socialistic. Waving a fist, Murray ordered the gentleman from Ohio to “shut up,” going so far as to threaten to “call the officers here and have you removed from the room.”

As the legislative lions kept at it, their roars resonating in the green and gilt U.S. Capitol hearing room, the Senate momentarily shed its carefully maintained politesse, descending into what a reporter called “a fist-shaking verbal brawl.” The indecorous exchange should have been no surprise; Murray’s panel was considering a proposal with the power to provoke hysterical reaction, especially since the legislation at hand seemed on the path to success: compulsory national health insurance.

On November 19, 1945, Harry S. Truman had thrown the weight of his office behind such a program, something not even Franklin D. Roosevelt had dared push. It was a daring move for an unelected president who 13 months before had been an obscure senator, but Truman saw the issue as one of fairness. Wealthy Americans could afford medical care. Poor Americans got charity care. However, Americans in the middle were out on a limb. Serious illness or injury could and did gut family finances; at some point, nearly a quarter of the population had gone into debt to pay medical bills. Americans were not getting the health care they needed, the president said, citing how during World War II pre-induction physicals found five million men medically unfit for military service. Health care would never be affordable for all “unless government is bold enough to do something about it,” Truman told Congress.

The president unveiled his insurance plan only seven months after taking the oath of office and three months after Japan’s surrender had ended World War II. Under Truman’s proposal, a 3 percent federal payroll tax on incomes up to $3,600 would pay for medical, hospital, and dental care for an estimated 110 million Americans, about 80 percent of the population. All eligible persons would be required to enroll. The federal government would pay medical bills in full, with no deductibles or co-payments. If revenue from the payroll deduction did not cover the plan’s cost, the government would make up the difference.

Truman knew he faced a fight in Congress. At the merest mention of government health insurance, the influential 126,000-member American Medical Association bristled, and many Republicans wanted to cut, not expand, New Deal social-welfare programs. Still, the odds seemed to favor Truman. His Democrats held comfortable majorities in both houses of Congress. Nearly three-quarters of the public favored national health care. Organized labor, a potent force in a country with more than 14 million unionized workers, backed his proposal.

The window of opportunity for achieving this milestone, however, was small and shrinking. The Republicans, who had been out of power since 1933, were hoping to retake Congress in midterm elections that were less than a year away. In that fleeting interim might reside Truman’s best—and perhaps only—chance to enact national health care coverage.

Reformers had been urging such a program in some form for decades. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party had promised “[t]he protection of home life against the hazards of sickness…through the adoption of a system of social insurance…” Universal care seemed poised to gain traction in late 1932, when the Committee on the Costs of Medical Care, a group of 48 medical professionals and economists, endorsed the principle, and President-elect Roosevelt seemed to agree. Roosevelt voiced hope that the committee’s work would lead to affordable care “for those to whom the disaster of illness would mean destitution.” Once in office, however, FDR about-faced. Health coverage seemed a logical companion to what was then called old-age insurance. However, in structuring the Social Security Act, Roosevelt avoided any mention of health coverage for fear of scuttling the entire bill. Social Security became law, but when House and Senate members introduced health-insurance bills in 1939 and 1943, Roosevelt pushed neither, and both died in committee.

Truman was a different story. In the 1920s, he had seen hospitals turn away people unable to pay, and he had done something about that. As county executive of Jackson County, Missouri, he had built an 88-bed public hospital. Truman knew that, for most Americans, it was “a real sacrifice to pay ordinary doctor bills,” and he wanted to use his presidency to help them.

“We are a rich nation and can afford many things,” he told Congress. “But ill-health which can be prevented or cured is one thing we cannot afford.” To launch Truman’s effort, veteran New Dealers Murray and Senator Robert F. Wagner (D-New York) and their colleague, Representative John Dingell Sr. (D-Michigan), introduced the National Health Act (S. 1606 and H.R. 4730).

Public reaction to the National Health Act was mixed. Some viewed the bill as “a wise and forward-looking extension of the New Deal,” Time magazine reported, observing that others were “sick & tired of having government do things for folks that they might be doing for themselves.” In The New York Times, a half-page ad backing the bill listed 198 notable supporters, including former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, RCA president David Sarnoff, and General Electric president Gerard Swope.

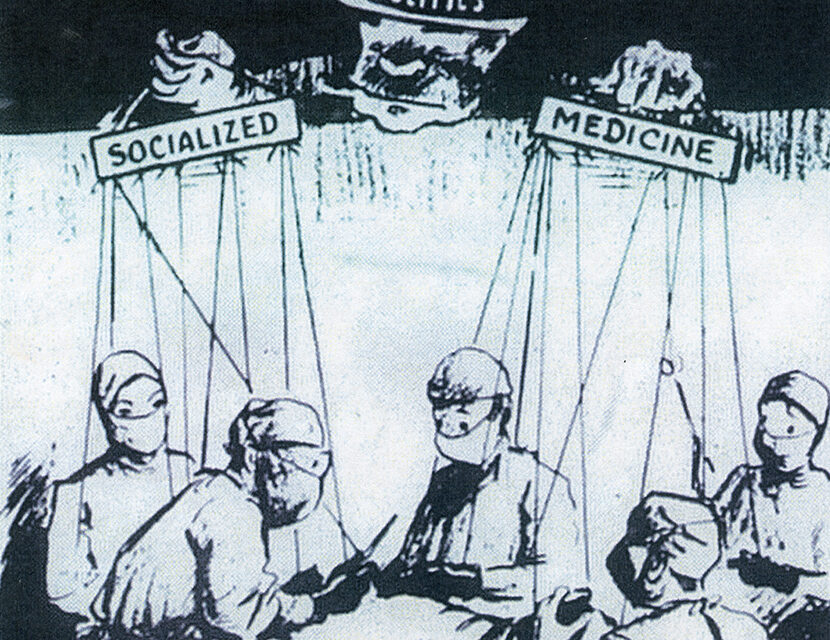

Republicans attacked. Taft called the bill pure socialism. House Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr. (R-Massachusetts) accused Truman of “out-New Dealing the New Deal.” A vitriolic AMA labeled the legislation’s aim the imposition of “socialized medicine.” According to the physician trade group, the bill marked “the first step in a plan for general socialization not only of the medical profession, but all professions, business and labor.” Morris Fishbein, MD, editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, denounced the National Health Act as “the kind of regimentation that led to totalitarianism in Germany and the downfall of that nation.” The National Grange, a farmers’ organization, attacked the concept of compulsory medical insurance for being “as un-American as the Gestapo.”

Growing anti-communist fervor made the phrase “socialized medicine” a damning indictment; supporters of the bill rushed to neutralize the invective. Truman called his plan simple insurance, no different than fire coverage, and warned Americans not to be “frightened off from health insurance because some people have misnamed it.” Co-sponsor Wagner accused opponents of stretching the term “socialism” to cover anything “to which the American Medical Association leadership is opposed.” Dingell said critics who insisted on labeling the plan socialism were “either woefully ignorant or inexcusably rigid in their stand-pat attitude.”

Those cries of socialism centered on the program’s compulsory structure. All eligible persons would have to enroll. Payroll deductions from healthy enrollees would cover care for the sick and injured. To Senator Claude Pepper (D-Florida), this was no more socialistic than requiring a bachelor to pay property taxes to support his jurisdiction’s local school district. The mandate arose out of mathematical necessity, supporters said. If the plan were voluntary, those likeliest to enroll would be people with pre-existing health conditions and those at the greatest risk for illness, the category insurers called “incipient hospital cases.” Healthy Americans might roll the dice and opt out. Insuring too many sick people and not enough healthy people would trap the program in a financial quagmire.

What opponents savaged as “socialized medicine” was nothing new in the United States. In 1798, concerned about the wellbeing of merchant seamen in a young nation dependent on maritime commerce, Congress passed and President John Adams signed into law the Seaman’s Act. This statute assessed each sailor a mandatory payroll tax of 20 cents per month. The funds went to build government hospitals and hire doctors to care for sick and injured seamen. Enacted on July 16, 1798, this program and its Marine Hospital Service functioned as intended for many years, in 1912 becoming the U.S. Public Health Service.

At 10 a.m. on Tuesday, April 2, 1946, the Senate Education and Labor Committee opened hearings on Truman’s health care plan. Within moments, Murray, 69, and Taft, 56, were exchanging verbal volleys. Murray, a liberal stalwart, was known for having a temper. Second in seniority to ranking minority committee member Senator Robert M. LaFollette Jr. (R-Wisconsin), the conservative Taft was the panel’s most prominent Republican. A deep-dyed nemesis of social welfare programs, Taft behaved, The New York Times wrote, as if he were on “a mission so right and so urgent that only the stupid or the stubborn would refuse to see it in the same way.” Each man had a personal stake. Murray was among the health insurance bill’s sponsors. Taft was eyeing the 1948 GOP presidential nomination.

Murray called Taft’s accusations of socialism “a grandstand play” and “slander,” but his grandstanding vow to eject Taft was more theater than threat. The only security staff present was one elderly U.S. Capitol police officer.

“You are so self-opinionated, and you think that you are so important that you can come into this meeting and disrupt it,” Murray snapped at Taft.

“Mr. Chairman, I am not going to attend any more meetings of your committee,” the red-faced Republican retorted. “We are through.”

Accusing Murray of employing the panel’s hearings as a “propaganda machine,” Taft, briefcase in hand, stormed out. The proceedings continued, but Taft’s outburst demonstrated that the Republicans intended to offer last-ditch resistance to government health insurance.

Organized medicine opposed the Truman bill by deploying a deep-pocketed and masterful public-relations offensive. Showdown on Political Medicine, a 24-page AMA-sponsored brochure, painted compulsory national health insurance as “an unusual crisis of great peril,” casting the National Health Act as a “strictly totalitarian” measure embodying “the most vicious and dangerous aspects of socialized medicine.” Institution of national health insurance coverage, the AMA warned, would “establish a core of collectivist control under which freedom of enterprise in any form could not long survive.”

Mailed in bulk to doctors and druggists, Showdown had broad reach. Physicians displayed the brochure and distributed copies to patients, sometimes mailing them with invoices. Pharmacists did the same. To reinforce the messages, the AMA ran newspaper ads blasting the Truman proposal. The campaign was officially the work of the National Physicians Committee, which bill supporters called a front set up by the AMA to protect its tax-exempt status by insulating the parent group against complaints of lobbying. A more extreme organization, the American Association of Physicians and Surgeons, threatened to boycott any national health insurance program. Organized medicine’s blitz was, New York daily PM editorialized, a “$300,000-a-year smear campaign.”

Opposition among doctors was not monolithic, however. AMA member Ernst P. Boas, MD, testified in favor of the Truman bill, accusing the AMA of “serving as a guild battling to retain the economic privileges of the medical profession.” Senator Murray chided doctors balking at the proposal as “more interested in high-fee luxury practice than in extending medical care for the masses of our people.” Concern over doctors’ income puzzled the Rev. Alphonse Schwitalla, president of the Catholic Hospital Association. “This is the first time in the history of the United States that people are beginning to worry about the poor doctor,” he said. “Up to now, it has always been the thought that the doctor will get the last benefit off the dead person’s eyes, and he won’t give you a death certificate until your bill is paid.” Whatever physicians’ motives might have been, income constituted a legitimate concern. Truman’s plan was murky on how and how much the insurance program would pay participating doctors.

Though the powerhouse AMA implacably opposed the bill, smaller physician groups backed Truman’s effort. These entities included the 1,000-member Physicians Forum, the 1,500-member Committee of Physicians for the Improvement of Medical Care, and the National Medical Association, representing several thousand African-American doctors. A Seattle MD wrote to the committee to voice support, but anonymously, because if he gave his name, he said, “retributive measures in one form or another would surely be my lot.” He signed his comments “A Doctor Ashamed of Doctors.”

All sides were in agreement that for many Americans medical bills were a strain. Health care costs had risen 15.1 percent since 1941. Both the Republicans and the AMA offered alternatives to Truman’s plan. Taft sponsored a bill—S. 2143—that would give the states $230 million to pay for care—but only for the very poor. Labor recoiled at a means test. “It is hard enough to be poor without being required to prove it if your kids get sick,” said George F. Addes, secretary-treasurer of the United Auto Workers. Taft’s bill went nowhere.

The AMA, portraying government involvement in health care as unalloyedly evil, pushed for voluntary private insurance, such as the nonprofit Blue Cross plans, relative newcomers that had arisen almost as a fluke. In 1929, Baylor University Hospital in Dallas, Texas, was in bad financial shape, partly because so many hospital bills were going unpaid.

To stop the fiscal hemorrhage, the facility hired administrator Justin Ford Kimball. To boost Baylor’s cash reserves, Kimball, 56, devised a system of prepaid insurance. For 50 cents per month paid in advance directly to the hospital, the plan guaranteed enrollees 21 days per year of inpatient care that the Baylor facility at no additional cost. To make this structure work, Kimball needed a critical mass of subscribers, so he approached the Dallas school system. By December 1929, 1,356 Dallas teachers—more than three-quarters of the district’s educators—had signed up.

One was Alma Dickson, a speech and drama teacher at John H. Reagan Elementary School. Only days after her coverage took effect, Dickson, 49, broke an ankle. She had her fracture set at Baylor; the Kimball plan paid her bill. Seeking more enrollees, Kimball pitched his program to the Dallas Morning News. First to sign up at the daily was Marion Snyder, 23, a clerk in the paper’s morgue. Within 24 hours, Snyder came down with acute appendicitis. She was rushed to Baylor’s emergency room. When the Kimball plan paid her bill, the entire News staff enrolled. By 1934, the Kimball plan was serving 408 employee groups and 23,000 members in Texas. With the Depression tearing at hospitals, enthusiasm for the arrangement spread to other states, which set in motion their own independent plans. Wanting to develop a brand, a Baylor-style plan in Minnesota settled on a blue cross as a symbol. Other plans adopted the emblem. By 1946, the Blue Cross system was operating in 43 states and covering 21.5 million people, about 15 percent of the population.

But Blue Cross was no cure-all. The plan covered inpatient costs, not doctor bills, a serious shortcoming as antibiotic drugs and other advances increasingly shifted care from hospitals to doctors’ offices. Only members of a participating employee group could enroll. Geographically, coverage was spotty, and in 10 states, Blue Cross plans insured less than 5 percent of the population. Plans that covered physician care, eventually known as Blue Shield, were in their infancy, insuring only 250,000 people.

As the Senate hearings ground on through May and June, the Truman proposal’s cost became a serious issue. The bill stipulated that the government would pay the difference between the revenue obtained through payroll deductions and the plan’s actual cost—and no one knew that cost. Social Security Board Chairman Arthur J. Altmeyer estimated the plan’s cost at $3 billion yearly, with payroll deductions falling $500 million short. Health care economist Elizabeth W. Wilson testified that the plan would cost considerably more, leaving taxpayers on the hook. There was a crucial unknown: if cost was discouraging people from seeking medical care, would having supposedly “free” care encourage hordes to seek treatment? Truman administration budget director Harold D. Smith conceded there was “no adequate control against the contingency of run-away costs resulting from excessive services…”

The president’s plan was in trouble. Still acclimating to Oval Office life, the usually combative Truman was strangely passive. He gave no fireside chats and embarked on no nationwide speaking tour to rally support, and his plan never captured the public’s attention. A May 1946 Gallup poll showed that while the majority of Americans favored national health insurance, less than 40 percent had heard of the pending bill. Support in Truman’s own party wavered. In an anonymous Associated Press poll of Congress, only 38 of 63 responding Democrats stood firmly in Truman’s corner. Organized labor was Truman’s ace in the hole, but unions were distracted from putting their full might behind the bill by big strikes during 1946. In January, 200,000 electrical workers struck. That month, 750,000 steel workers walked off the job, threatening a cascade of industry shut-downs. In April, 400,000 coal miners struck. When 250,000 railroad workers did so in May, paralyzing a nation deeply dependent on rail, Truman angered labor leaders by threatening to draft strikers into the U.S. Army.

The Education and Labor Committee still had hearings scheduled, but the congressional election recess was near, another factor siphoning time and urgency from the bill’s progress.

That November, all House seats and a third of Senate seats were up for grabs, and Congress was to adjourn on August 2 so members could campaign. The National Health Act, The New York Times wrote, was “loaded with too much controversy for its sponsors to expect it to reach a voting stage before the election year adjournment begins.” On July 10, 1946, Murray canceled further hearings, informing scheduled witnesses they would not have to appear. Supporters vowed to renew the fight in 1947, but the moment had passed.

The 1946 elections were a disaster for Democrats. Republicans, campaigning on the slogan “Had Enough?”, gained 13 seats in the Senate and 56 in the House to take control of both houses, making Congress a death trap for national health insurance. That skew remained even after November 1948, when Truman came from behind to win election and the Democrats regained control of Congress. The Cold War made the socialized-medicine label more damning than ever. The AMA trumpeted a quote attributed to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin calling socialized medicine “the keystone to the arch of the Socialist State.” Senator Murray had the Library of Congress fact-check the ostensible quote, which was found to be bogus. Health insurance bills floated in 1947 and in 1949 were dead on arrival.

In 1950, with the Korean War under way, Truman waved the white flag in regard to health insurance. That October, Representative Dingell, a sponsor of health care bills since 1943, wrote to the president complaining about organized medicine’s obduracy.

“At the proper time we will take the starch out of them,” Truman wrote back. “I don’t think the time is exactly right to do that.” The time never did become right for Truman. He later called his insurance plan’s demise the greatest disappointment of his presidency, remarking that he never could understand “all the fuss some people make about government wanting to do something to improve and protect the health of the people.”

Presidents since have enacted ambitious schemes—Lyndon B. Johnson with Medicare in 1965 and Barack Obama with the Affordable Care Act in 2010—but none has proffered a plan as bold or far-reaching as the program Truman did. Universal health care remains a wedge issue, to some a dream, to others an anathema—with no more consensus than in 1946 and no answer in sight.