Settlers created fresh, colorful words and phrases to describe their land and life

[divider_flat]THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE started to become American as soon as the first English-speaking colonists landed. Unfamiliar landscapes, plants, and animals and ways of living called for new terms, and Americans soon were amassing a fresh vocabulary. Colonists borrowed from natives—raccoon, barbecue—inventively combined existing words—backcountry, pine barrens—and coined terms—demoralize, belittle. However, American speech was about more than words. Early Americans distilled vivid metaphors from everyday life. They blazed trails. They played possum. They found themselves sitting on the fence. They barked up the wrong tree. They improvised outlandish fabrications like scrumptious and blusteration.

[divider_flat]From the beginning, certain facets of American life especially encouraged fresh, colorful language. Among these were the boisterous world of politics, source of caucus and gerrymander; the striking landscape, with its buttes, prairies, and swamps; the press, so fond of slang like fizzle out; and especially the Western frontier.

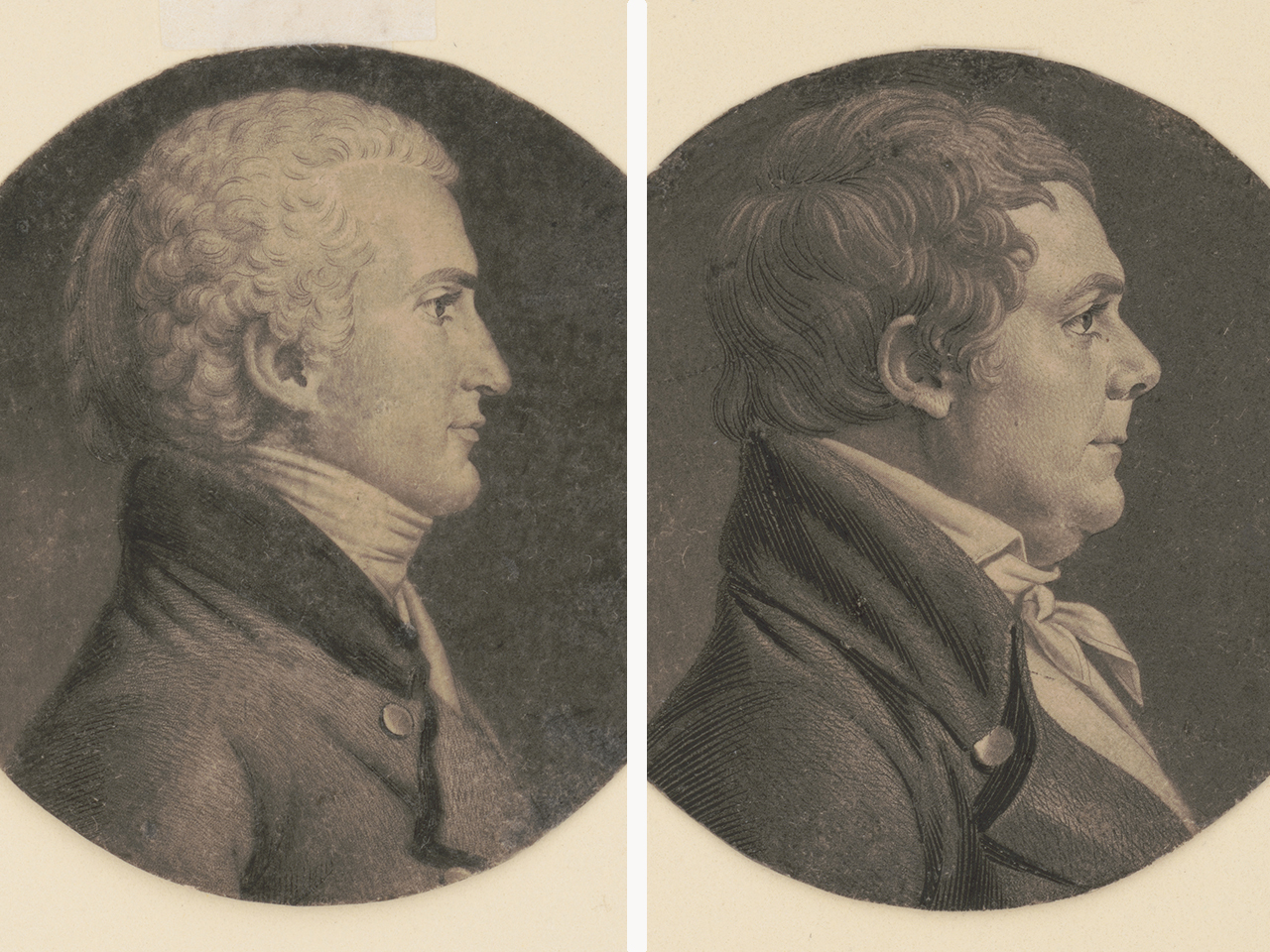

In 1775, Daniel Boone, a hunter and trapper born in western Pennsylvania, led a party of about 30 men across the Appalachian Mountains through the Cumberland Gap into the Kentucky Territory, blazing what became known as the Wilderness Road. After the Revolutionary War, England ceded to the United States of America all territory running west to the Mississippi River. The first rush of words from that region came courtesy of explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, whose Corps of Discovery was to map the Louisiana Territory, which Napoleon had just sold to the United States for $15 million, or 3 cents an acre, and of which Americans knew little. Sending Lewis and Clark off to trek the continent, President Thomas Jefferson assigned them to collect detailed information on every aspect of territories they passed through—plants and wildlife, topography, climate, and native societies. In their effort to characterize what they encountered, the leaders of the Corps of Discovery created nearly 2,000 words and phrases—inventing new compound words, giving old words new meanings, and borrowing words and phrases from the people they encountered during their trip.

After months of training and preparation, the corps set out in May 1804 from St. Charles, Missouri, journeying up the Missouri River in a 55-foot keelboat and two supply-laden craft probably constructed from planks even though they were called pirogues, a French word originally used to describe canoes hulled out from a single tree trunk. They launched onto the Missouri River intent on reaching the Pacific, which they did, a grueling odyssey that lasted more than two years.

Besides commanding the explorers to map their route “with great pains and accuracy,” Jefferson ordered Lewis and Clark to note significant natural features, including “the soil and face of the country;” unusual plants; animals, “especially those not known in the U.S.”; minerals, especially limestone and pit coal; and climate, including extremes of temperature, an inventory of cloudy and clear days, first and last frost dates, and prevailing winds.

Lewis and Clark amply met Jefferson’s requirements. Their journals brimmed with careful descriptions. Even as they were crossing the northern plains, portaging around falls, struggling through mountains, and canoeing western rivers, Clark and Lewis each wrote his journal nearly every day, meticulously recording every notable feature. As necessary, the explorers created language to do justice to what they were seeing. Many terms they repurposed, invented, or borrowed entered the American lexicon (see also “Webster’s Book Tour: The Making of the First American Dictionary“). An easy way to create a term was to combine a familiar noun with an unexpected modifier to convey appearance, behavior, or use. Lewis and Clark cobbled together such assemblages by the hundreds, embodied by the way they arrived at a name for an unfamiliar deer species

Crossing the plains of what is now South Dakota on September 17, 1804, Clark records in his journal that one of the men has killed “a curious kind of deer (Mule Deer).” He makes clear why he’s giving the animal that name—“the ears large & long.” The tail’s tip is “a tuft of black hair,” so Clark sometimes refers to “black-tailed deer” before concluding that the creature’s long ears make mule deer much more appropriate.

Lewis mentions black-tailed deer in his journal, too, but he means another kind of animal. On February 19, 1806, at Fort Clatsop, Oregon, he describes a variety of deer seen in the Pacific Northwest. “The Black-tailed fallow deer are peculiar to this coast,” he writes. Like mule deer, this animal has ears “rather larger than the common deer.” The tail’s underside is white, with “quite black” hair along the sides and top. Lewis says he considers the animal similar to but not the same as the mule deer, concluding that the Oregon black-tailed deer is its own subspecies. It’s a tribute to Lewis’s powers of observation that zoologists seconded his assessment. They gave the mule deer the scientific name Odocoileus hemionus; the other they dubbed Odocoileus hemionus columbianus, common names mule deer and black-tailed deer, the labels Lewis and Clark assigned.

Often the explorers named a plant or animal for its salient features or behavior. Terms that debut in the journals include bighorn sheep, black woodpecker, tiger cat (a lynx), red-tailed hawk, red elm, and snowberry. Sometimes they named animals for their behavior, as with the tumblebug (a beetle that rolled animal dung into balls for later consumption), burrowing squirrel (a ground squirrel) and, in the case of a small swan Lewis saw along the Pacific coast whose call was a “peculiar whistling note,” the whistling swan. The men identified plants and animals by habitat—prairie lark, Osage apple, mountain trout, sandhill crane—and use— buffalo grazed in buffalo grass and to spear fish Indians used a gig pole.

The explorers preferred English words when naming finds, customizing common terms to fit unfamiliar species or subspecies: blue jay, dogwood, and tree frog, to name a few. However, they did borrow terms from French traders and boatmen. Few Francophone names stuck. For instance, cabrie is French for antelope, a term Lewis and Clark sometimes employed, but that use faded to nothing.

Lewis and Clark borrowed from native languages, though the difficulty of fitting these terms into English kept most from being adopted. There were exceptions: the Nez Percé camas referred to a plant with an edible bulb, the Ojibwe kinnikinnick identified a tobacco substitute, and the Cree pemmican, meaning a cake of dried meat, fat, and crushed berries. Emulating earlier English speakers, the men attached Indian as a modifier: an Indian hen was a small bird also known as the bittern; Indian tobacco was the leaf of a type of lobelia that was dried and smoked. Clark and Lewis were among the first to use the translated terms council house, sweathouse, and sweat lodge. The pair introduced medicine as an adjective, probably a translation of an Ojibwe word which the explorers took to mean “whatever is mysterious or unintelligible,” employing it to define medicine bag, medicine dance, medicine man, and medicine song. The Great Spirit, again probably from the Ojibwe, was already afoot, but Lewis and Clark helped popularize it. In the same journal entry in which he explains medicine, Lewis connects “big medicine” with “the presnts [presence] of the great Sperit.”

Emigration beyond the Appalachians initially was a trickle but by 1840 many settlers had swarmed beyond that obstruction. Typically, these travelers moved directly—southerners into what are now Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Alabama, those from farther north trekking into what became Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

Western settlers were adding words even before they arrived, beginning with their means of conveyance. In the 1700s Mennonites inhabiting a Pennsylvania valley named for an Iroquoian tribe once dominant there and in parts of neighboring Maryland built a sturdy freight wagon whose design and four-horse propulsion lent themselves to long-distance transport. The Conestoga wagon was 16 to 18 feet long, wider at the top than at the bottom, with canvas stretched over hoops shielding its cargo space. The term covered wagon was in use by the mid-18th century. Wagon train came in shortly afterward.

When the western exodus began, the Conestoga’s durability and capacity made it a popular choice, except with pioneers heading all the way to Oregon. These travelers preferred wagons known as prairie schooners, prairie clippers, or prairie ships for their resemblance to sea vessels—the term dates to the 1830s. A stagecoach traveler near Chicago writes about the appropriateness of the name: “We met many large wagons, which well deserve their name of ‘prairie schooners,’ as their white covers show like sails at a distance.”

Westbound American encountered unfamiliar and often rugged terrain. Like Daniel Boone traversing the Appalachians, they passed through gaps—relatively low and navigable passes—and over divides—ridges that separate watersheds. North America’s most notable divide—the Continental—is the crest that runs the length of the Rocky Mountains, separating drainage to Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Low-lying lands along rivers were flats. Barren, already extant, saw more frequent use as a noun. Pine barrens—used to name a sandy expanse of stunted conifers and shrubs in southern New Jersey—was applied to similar areas abundant on the Kentucky frontier.

Much of the land settlers hoped to claim was dense with bushes, saplings, vines, and other low-growing plants they called brush—short for brushwood and referring not only to ground cover but also to fallen or lopped tree branches and other wood unsuitable for use as cordwood. From brush came brush heap, brush fire, and underbrush.

East of the Mississippi, the frontier was thick with what Americans since the 18th century had been calling timber, meaning trees suitable for felling and sawing into useful forms. Back in England, timber meant wood that had been processed for building—what Americans called lumber. In England, lumber meant and means discarded furniture or other household junk. In the New World, timber could mean trees themselves or forested woodlands. Someone escaping into the forest was heading for the tall timber.

At the frontier, pioneers’ first order of business was to find a piece of land and lay claim to it. Ownership rights were confused and hard to enforce—the government owned some land, while other areas belonged to Indian tribes, at least in theory. Often newcomers, to use an 18th century term seeing wider use, squatted, settling on a parcel without benefit of title.

Americans had been on the move since they first arrived, a cycle often characterized as setting stakes and pulling up stakes, referring to the stakes that held a tent erect. To this corner of the lexicon was added stake a claim, meaning to pound stakes to mark the boundary of land one was claiming. In England, lot had been a vintage word for property of any sort, especially an inheritance, but Americans held it to mean land, especially land on which to build—perhaps traceable to Massachusetts settlers’ method of distributing parcels of land by drawing lots. House lot entered American English in the 17th century, back lot in the early 18th, and corner lot in the early 19th. To go across lots was to ignore obstacles. Mormon pioneer Brigham Young famously told enemies to “go to hell across lots.”

Frontier residents tended to settle close enough to one another to be able to call on each other in times of need. Cooperation was not restricted to emergencies; collective enterprises were known as bees, probably an allusion to that insect’s communal industriousness. Raising bees brought neighbors together to frame houses or barns. Women gathered for quilting bees to make coverlets and men for chopping bees to split logs for rails or firewood. Young people might convene for paring bees, also called apple bees, peeling and slicing apples for drying. Such events were social occasions, with beneficiaries providing food and drink. The one bee most modern Americans know—the spelling bee—only came into fashion after the Civil War.

Besides spawning myriad words, the trans-Appalachian frontier birthed a flamboyant mode of self-expression long on exaggeration. Westerners loved extravagant adjectives such as awful, powerful, monstrous, dreadful, mighty, almighty, and all-fired. Outlandish etymological concoctions—bodacious, rambunctious, and highfalutin(g)—were a feature of the West, whether coined or popularized on the borderlands.

Dozens of expressions evocative of frontier life started with literal meanings but evolved into metaphors—eat crow, eat dirt, make the fur fly, paddle one’s own canoe, be up the creek without a paddle, rope in. The region’s emphasis on hunting is obvious in loaded for bear (ready for anything), and weaponry’s importance in lock, stock, and barrel; draw a bead; and flash in the pan, the last meaning an attempt to fire a flintlock rifle that failed because the priming powder, piled on a surface known as a pan, burned but did not ignite the main charge. Timber country conversation inspired easy as falling off a log and more than you can shake a stick at. Government premises set up to distribute land gave rise to the expression do land-office business, meaning to be very busy.

Davy Crockett—he preferred David—was the apotheosis of the frontier word-slinger—tough, bold, resourceful, and at home in the tall timber and the halls of Congress. A descendant of Ulster Scots settlers, Crockett had grown up in extreme poverty. His education was minimal—he claims in his autobiography that he didn’t learn to read until he was 15—but was elected to the House of Representatives in 1827. What Crockett lacked in polish he made up for in straight talk. His motto was “Be always sure you’re right—then go ahead.”

Back east before his demise, Crockett had been an object of wonder—an informal ambassador from a land that to most American still seemed wild and strange. He popularized expressions forged in the trans-Appalachian West—chip off the old block, a hard row to hoe, be stumped, go the whole hog, root hog or die (work hard or lose out), fire into the wrong flock (mistake your target), and bark up the wrong tree. He often used the last expression when his hunting dogs surrounded the base of a tree other than the one concealing his prey. He also used it figuratively. In a letter about the politics of the day, he writes, “Some people are going to try to hunt for themselves . . . but . . . seem to be barking up the wrong sapling.” Legends and tall tales grew around his larger-than-life persona, which was based on his way of talking—frontier speech writ large, full of fanciful word inventions, wilderness metaphors, and outsize boasts. The posthumous 1837 Davy Crockett’s Almanack, written by others, relies on all three categories of self-expression. In the preface, he repeats his message to constituents before the 1835 election, which he lost: “If they did not re-elect me, they might go to hell and I’d go to Texas.” The Almanack intersperses weather predictions and other generic material with flights of verbal fancy in the Crockett mold, like “A Tongeriferous Fight with an Alligator” in which “Crockett” describes the wild rampoosings of saurians atop his house and the rageriferous wrestling he had to undertake to roust them. In another piece, “Crockett” describes Texas as a land “so rich, if you plant a crowbar at night it will sprout tenpenny nails before morning.” Countrified vocabulary and nonstandard verbs abound. “I was so wrothy I should have scun him alive,” the narrator declares. “I div down in a slantidicular direction.” Pestered by a “yankee peddler,” he threatens, “If you ain’t off in no time, I’ll take off my neckcloth and swallow you whole.” Crockett’s freewheeling speech and that of fellow frontier dwellers appealed to anyone inclined to use language for effect, spicing up newspaper editorials and injecting into campaign speeches—stem winders, as in keeping a watch running delivered on the stump, as in a handy place for a roving politician to get onlookers’ attention—a folksy touch, turning up occasionally in the Congressional Record and in time becoming essential to the American vernacular.