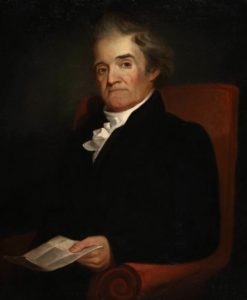

Noah Webster’s prescient book tour was an exercise in survival

“I CURSE ALL stage Waggons,” a furious Noah Webster wrote in his diary entry for May 18, 1785. Webster had been on his way that day from Baltimore, Maryland, to Alexandria, Virginia, when the coach in which he was a passenger overturned, bouncing him back to the Maryland port. The next day, still cursing stagecoaches, Webster hired a horse, arriving in Alexandria that evening after a 50-mile ride.

Webster was undertaking what likely was the first multi-city book tour by an American author. The writer had left his home in Hartford, Connecticut, on May 2, planning to range as far as

South Carolina, selling books in major towns along the way. Webster also wanted to do what he could to keep his work from being pirated by printers—a constant danger in the days before federal copyright laws—so he planned personally to

register his books with individual state legislatures.

A recent Yale graduate and would-be lawyer, Webster was teaching school in Hartford when he wrote the Grammatical Institute of the English Language. The three-volume set, which Webster published between 1783 and 1785, addressed the core of 18th-century literacy: a grammar book, a speller, and a book of practice readings. His books were the first language textbooks written by an American for Americans.

Noah Webster arrived at authorship by an unusual route. The fourth of five children born to John and Mercy Steele Webster, the boy grew up on a farm in the hamlet of West Hartford. As was true for most farm children, his formal education consisted of a few years at the local grammar school. But he loved books and words; according to family lore, while working in the fields he carried a Latin grammar that he read on breaks. By age 14, he knew he wanted to attend college. Alone among his siblings, he did so; his years at Yale set him firmly on the path to a life of scholarship and writing. He first set out to be a lawyer, but when legal work proved scarce in the post-Revolutionary War depression, he took up teaching, which led him to try his hand at textbook writing. Webster harbored hopes of producing volumes that would replace the British imports most American schools used.

Webster had some success with the speller, but sales of the other two volumes lagged. Most schools persisted in relying on grammars and readers from England. To enhance his promotions, Webster devised an innovative scheme: he would pitch books to buyers state by state and city by city, rather than flog them regionally and wait for orders.

The 18-month promotional trip was a gamble, economically and physically. But the effort paid off—for the man and for his country. That road trip inspired the monumental dictionary known to the world as “Webster’s.”

Webster had his eye on more than sales. A patriot, he believed that fellow citizens deserved textbooks designed for them, not English imports. His books featured material of interest to Americans, such as lists of place-names and monetary values. Webster promoted the study of homegrown American English, and he was willing to pay a personal price to get out the word.

The writer usually traveled on horseback, stowing his possessions in two heavy saddlebags. Between towns, as in the Baltimore-to-Alexandria run, the author occasionally went by coach. He shipped his inventory aboard sloops that darted along the coast to serve ports and transporting goods and people inland by way of rivers. Sometimes Webster himself traveled by sloop, although stagecoach did offer attractively cheap and convenient passage between towns. Had Webster’s May 18 trip not come to grief, he would have spent less than a day on the road, probably for only a few dollars.

The 1,300-mile Main Post Road connected Wiscasset, Maine, and Savannah, Georgia, with stagecoaches, typically pulled by four-horse teams, departing either terminus several times a week. In between, coaches stopped at major coastal cities. Each leg was called a stage, giving the vehicle its name. Also known as stage wagons, coaches were about the size of freight wagons, with a rounded underside and a light roof set on four narrow pillars. The coach rode suspended on leather thorough braces. Canvas or leather curtains attached to the roof could be rolled up or left hanging, depending on the weather. Inside, three backless benches seated three passengers each. There were no side doors; passengers scrambled in over the front of the coach—and, if boarding late on a run, over seated passengers. A 10th traveler could sit beside the driver.

A coach trip meant hours bouncing on the hard benches, awash in luggage, mail, and other goods, leaning against fellow passengers as the vehicle swayed along. When the coachman dropped the curtains, the interior was plunged into darkness. Accidents were common. Wheels could collapse. A snapped central brace could drop a coach to the ground. Breakdowns too serious to repair sent passengers and coachman walking to the nearest town.

Outside towns, roads were rough and poorly maintained, dotted by stumps, boulders, and other obstacles and for much of the year impassable to wheeled vehicles thanks to mud and snow. Corduroy roads—tree trunks laid sideways in low-lying areas prone to sogginess—ensured dry passage at the expense of a jaw-jarring, spine-shattering ride. Rural areas, especially in the South, had few public roads. In such settings, travelers in coaches cut across fields and through woodlands.

Travelers generally relied on horses, surefooted and deft at avoiding obstacles. Riders bought mounts at the beginning of trips and sold them at the end, or hired a series of horses from livery stables, often allied with inns or taverns where a rider could eat and bunk and where horseback travelers could put up their animals.

Horses were not without risk. On a trip between Fredericktown and Baltimore, Maryland, on January 18, 1786, Webster’s mount fell, so badly injuring the author’s leg—which, he does not specify—that he limped for days. He managed to return to Fredericktown and rent another horse. In a historical footnote, the New Haven Museum owns Webster’s remarkably modern-looking saddlebags from this trip—alas, not on display but stowed in the basement.

Sloops were the most comfortable way to travel. Introduced by the Dutch, these small—40 to 60 feet stem to stern—light, and quick single-masted vessels first showed up on the Hudson River in the 1600s. In Webster’s day, fleets of sloops transported cargo ranging from timber and furs to dry goods and rum, hugging the Atlantic shore and tacking along rivers connecting cities and towns. Along with cargo, most sloops could hold at least a dozen passengers in quarters far more spacious than a stagecoach. Sloop passengers also got meals.

The little vessels’ primary drawback, as Webster learned sailing from Baltimore to Charleston, was the wind, or lack thereof. Webster set sail on May 31, 1785, expecting to spend a few days between ports. However, the sloop struggled with headwinds, then was becalmed, sometimes for days, taking two weeks to reach Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. By then food and water supplies were low; diarist Webster reports that crewmen harpooned a dolphin—“an excellent dinner”—and a few days later, a shark. Soon the captain was rationing water, “two quarts a day per man.” Not until June 26 did the beleaguered craft make Charleston Harbor.

Besides posing discomfort and danger, transport modes were slow. Even a fast horse covered only 40 or 50 miles in a day, so trips of any distance meant overnight stays. Leaving Connecticut, Webster headed for Baltimore, his anticipated base for forays to Virginia and the Carolinas. From Hartford he reached New Haven, overnighting before setting sail for New York City, a trip of two days. After several days in Manhattan visiting friends, the author spent six days on the road in New Jersey and Philadelphia before reaching Baltimore. Total time to cover those 320 miles: two weeks.

Webster sometimes stayed with friends, enjoying meals and drinks with acquaintances—although on extended interludes he usually rented a room in a private lodging house. Occasionally he stayed overnight at an inn en route. In New York, Webster notes, “Find many friends that I have not seen a long time.” He records, among other encounters, tea with Theodosia Prévost Burr, wife of Aaron Burr and a friend from the Revolutionary War years.

Webster encountered more famous figures, like George Washington, at whose home, Mount Vernon, the author spent a night. The author and his host and family discussed education, among other topics. When Washington remarked that he was considering hiring a Scot to tutor his step-grandchildren, Webster convinced the founding father to look homeward for pedagogical talent. What would European countries think, Webster asked, if, having displayed “great talents and achievements” during the War for Independence, Americans went abroad to recruited professional men?

Late in his tour, Webster met Benjamin Franklin, another student of the American language. The two began a correspondence. When Webster decided to travel north to lecture, Franklin arranged for his new friend to use a room at the University of Pennsylvania.

Bookstores were scarce, so everywhere Webster went, he hawked his wares, stacking his stock wherever he could rent or cadge space—often in a residence’s front room. In Charleston, he reports, “Open my books at Mr. Timothy’s and advertise them.” In Baltimore, Webster displayed his books at Mr. Snow’s, then at Miss Goddard’s. Ashore briefly in Norfolk, Virginia, the author left three dozen copies for a printer to sell. As opportunities arose en route, he sold printing and regional distribution rights to printers.

Webster had a sharp and calculating eye. He counted the number of houses in nearly every town he passed through, sharing his data with other statistically minded friends and foreshadowing the first census. He recorded that Baltimore had 1,950 houses, along with 150 “stores and public buildings.” Charleston boasted 1,560 houses until a fire at the heart of town burned 19 dwellings to the ground.

Alexandria had 300 houses; Williamsburg—of which Webster writes, “This is the most beautiful city in Virginia”—230. He thought Williamsburg houses “well-built” and the College of William and Mary “large and elegant.”

Among the peripatetic author’s pleasures were eating the season’s first cherries, witnessing a balloon ascent, and enjoying Independence Day in Charleston, which featured a cannon salute and a flourish of fireworks.

Intent on registering his books with state legislatures, Webster worked his schedule around those bodies’ sessions, sometimes revisiting a city or loitering there for weeks, waiting to catch legislators on duty. Between repeat excursions to Charleston and Richmond, Webster cooped in Baltimore, whose port and population of 8,000 offered myriad diversions. Almost daily, Webster socialized, took walks, dined, or had tea with new companions. He attended public balls. Twice he walked to the docks and toured vessels from the East Indies. He undertook to study French.

Lectures were a popular diversion, and Webster attended several, conforming to Americans’ enthusiastic belief in self-improvement. Lecture halls—a town of any size had at least one that booked representatives from the stream of inventors, scholars, preachers, and other personalities riding the circuit—were fonts of ideas and trends, stirring the intellectual pot in the context of a social event. Crowds at talks that Webster attended on topics as disparate as electricity and philosophy probably inspired a project the author launched to earn money while pursuing his love of language.

After several months on the road, Webster had run short on cash. He was selling books—and engineering advertising and copyright efforts that would boost sales—but it was a slow business and travel was expensive. Thinking to start a singing school, Webster held classes in Baltimore’s First Presbyterian Church on Fayette Street, where he and Patrick Allison, the young pastor, had become friendly. But American English remained Webster’s chief interest. One August afternoon he started writing his thoughts about the native tongue’s history and use. By early October he had completed five essays—“dissertations,” he called them. Over tea Webster read his musings to Reverend Allison, who liked the discussions well enough to offer his church as a setting in which Webster could present his thoughts to the public—for a modest fee.

Webster gave his first lecture on the evening of October 19, 1785, before 30 paying customers who had anted up a quarter for that presentation or seven shillings sixpence—$1—for the full series of five. That night Webster spoke about the importance of a national language. “As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government,” he said. Over the centuries, North America’s English speakers had evolved their own vocabulary and speaking style, he explained. Webster wanted Americans to take pride in their distinctive native speech rather than imitate the British.

Listeners raved. Each succeeding lecture drew a larger crowd. Fresh from winning the Revolution, Americans were in a patriotic mood, and caught up in the question of how different they should be from Brits. Webster was among the first advocates to encourage the embrace of specifically American English.

After his fifth performance, on October 26, Webster wrote in his diary, “The lectures have received so much applause that I am induced to revise and continue reading them in other towns.” Soon he was traveling again, speaking in Richmond, Alexandria, Annapolis, and other locales. Turning north to make for Dover, Delaware; Philadelphia, and Princeton, New Jersey, Webster moved quickly, covering 50 or 60 miles at a clip. He continued marketing his books in person and contracting with printers, but his talks about language had become as important a source of revenue and status as his other activities.

Webster returned to Hartford in June 1786 after nearly 13 months, staying only briefly. Soon he was touring New England, speaking in venues as small as “Mr. Hunt’s schoolhouse” and as large as Boston’s Faneuil Hall. In New York City, the author drew a crowd of 200.

Success did not inoculate Webster against disaster. Bound from Connecticut to New York in December 1786, he drove his sleigh into a snowdrift. Trudging to a town, the writer set out the next day during another storm, again burying himself in snow. Pushing on, he reached his destination after four “very cold” days. Despite having horses, he “walked much,” he notes.

Not long after those misadventures, parties in Philadelphia offered Webster a position as a schoolmaster in that city. He accepted the job, bringing his 24-month sojourn to an end. He counted his self-promotional venture a commercial success. Part I of the Grammatical Institute of the English Language, the speller, would become one of the first American best sellers. Parts II and III, the grammar and reader, became classroom fixtures despite low sales.

Webster’s innovative idea about the primacy of American English paid off in a remarkable way. He devoted several years to employment, including practicing law and editing a weekly newspaper, but never lost his yen to analyze and explicate this new language. In 1806, 20 years after his book tour, he published the first major American dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. A larger, more complete volume, An American Dictionary of the English Language, appeared in 1828, defining 12,000 Americanisms not previously recorded, such as iceberg, glacier, and magnetize. Webster included new coinages like parachute and safety-valve, and new verbs such as revolutionize, electioneer, quarantine, patent, and the only word the author claimed to have coined himself: demoralize. He formally defined the slang negative “ain’t.” and introduced new spellings—such as “waggon” instead of “wagon”—but not precipitately. His 1806 dictionary lists “waggon” as both noun and verb (“to convey in a waggon”), but the 1828 dictionary drops the second “g.”

In similar style, thanks to Webster, Americans write music not musick, center not centre, color not colour, and plow instead of plough. Maybe most significantly, Webster gave Americans pride in their speech.

Nearly 200 years later, American English is still building on Webster’s foundation, as the dictionary that bears his name goes into its fourth edition—online. Noah Webster changed the American language in lasting ways, and it all started with a road trip.