On March 30, 1972, some 30,000-40,000 North Vietnamese Army regulars streamed southward across the Demilitarized Zone and eastward from Laos in a strike against the recently formed 3rd Infantry Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Over the next month this force in northern South Vietnam would involve three divisions and two dozen independent regiments supported by 200 tanks, long-range 130 mm artillery guns and air defense units. About 60 miles to the south, another North Vietnamese division headed toward Hue.

The March 30 attack marked the opening of the North Vietnamese Spring-Summer Offensive of 1972 (Chien dich Xuan he 1972). The offensive consisted of a three-pronged assault that hit South Vietnam in its northern, central and southern regions. The goal was to destroy as many ARVN forces as possible, which would enable the North Vietnamese to occupy key cities and put communist troops in position to threaten Saigon and President Nguyen Van Thieu’s government, according to captured documents and information from NVA prisoners after the invasion.

Within two weeks of the initial attack across the DMZ, large battles were being fought on all three major fronts. Before the offensive was over, more than 14 NVA divisions and 26 regiments—totaling more than 130,000 troops and approximately 1,200 tanks and other armored vehicles—were committed to the fight. The North Vietnamese also brought advanced weaponry not used in previous communist offensives.

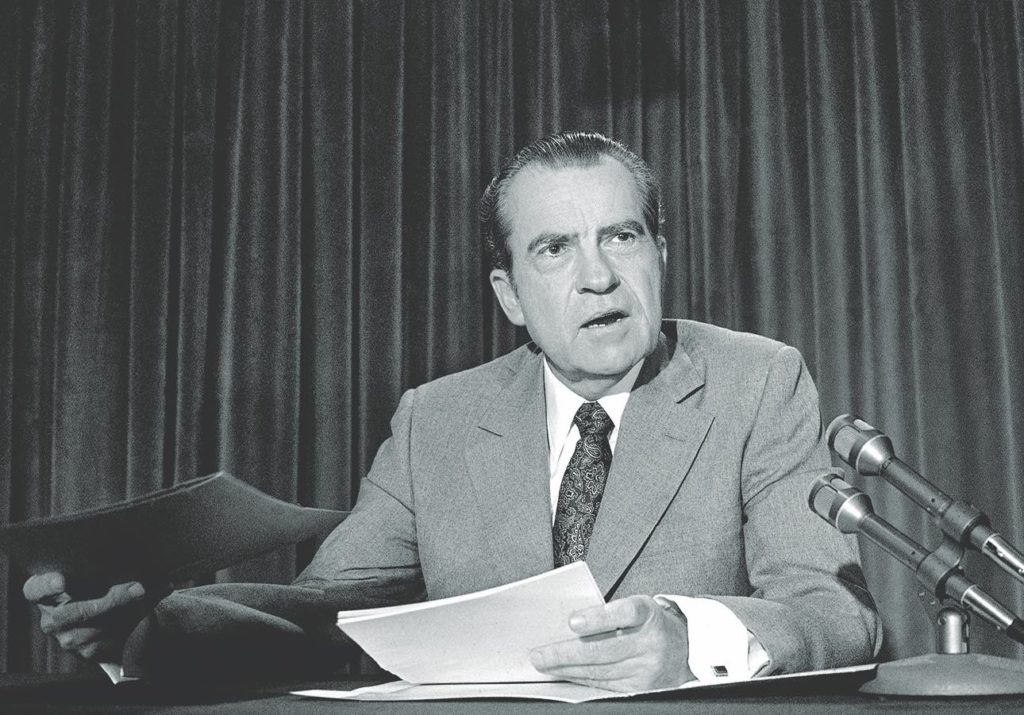

By this time, President Richard Nixon had instituted a “Vietnamization” program to turn the conduct of the war over to the South Vietnamese. This program, announced in 1969, was developed to increase ARVN capabilities and bolster Thieu’s government so the South Vietnamese could stand on their own against communist forces. Strengthening ARVN capabilities would permit the eventual withdrawal of all U.S. troops from South Vietnam.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, the senior U.S. headquarters for combat operations, increased the number of military advisers assigned to ARVN forces to improve their quality, a critical function of the Vietnamization program. Although MACV advisers had worked with South Vietnamese units since 1955, the importance of the advisory program increased as the number of American combat units dwindled.

By the beginning of 1972, most U.S. ground combat forces had been withdrawn, leaving 136,500 troops on Jan. 31. By the end of March, the number had dropped to 95,500. On April 30, it was only 68,100. Aside from a few remaining infantry battalions, the only Americans on the ground in combat roles were advisers serving with ARVN operations and South Vietnamese marine troops.

U.S. advisers assisted the ARVN at the corps, division and regimental levels. In South Vietnam’s elite airborne, ranger and marine units, American advisers also served with each battalion. Additionally, there were advisers in all 44 South Vietnamese provinces as part of the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support program, shortened to CORDS, which worked to gain the support of South Vietnamese living in the countryside. The ARVN forces were backed up by U.S. Army helicopter units, as well as aircraft from the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps. American forces continued to maintain a large presence in logistical operations to support the South Vietnamese forces.

In spring 1972, ARVN units were still recovering from the battles in February and March 1971 when they had made a limited incursion into Laos as part of Operation Lam Son 719, directed at NVA bases and supply depots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. South Vietnam’s forces continued to be plagued by corruption, poor leadership and politicization of senior officers. They relied heavily on U.S. support and firepower. It was clear that the South Vietnamese armed forces were a work in progress, and the Nixon administration realized their fighting capabilities had to be improved before the U.S. disengaged completely.

Meanwhile, in Hanoi, Communist Party First Secretary Le Duan and his right-hand man, Le Duc Tho, decided the time was ripe for a large-scale offensive to deliver a knockout blow that would end the war on the North’s terms.

They did not think the Americans had enough troops left in Vietnam to change the outcome once the offensive was launched and believed public disenchantment with the war in the U.S. would not permit Nixon to commit new troops or combat support to assist the ARVN.

Le Duan and Le Duc Tho reasoned that a resounding North Vietnamese military victory would humiliate the president, force his administration to negotiate a peace agreement favorable to communist forces and perhaps even derail the Republican president’s reelection bid in November 1972, putting a Democratic opponent of the war in the White House. If a complete victory could not be achieved, the North Vietnamese believed they might at least seize enough territory to strengthen their position at the Paris peace negotiations.

Defense Minister Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, perhaps remembering the military defeat of the 1968 Tet Offensive, urged caution, believing that the time was not right for another major offensive. However, Le Duan opted for a more aggressive strategy. Operational planning for the new offensive was led by Gen. Van Tien Dung.

Throughout the latter half of 1971, Hanoi requested and received large quantities of modern weapons from the Soviet Union and Communist China. These included MiG-21 jets, SA-2 surface-to-air missiles, Soviet T-54 (and Chinese variant Type-59) tanks, 130 mm guns, 160 mm mortars, 57 mm anti-aircraft guns and heat-seeking, shoulder-fired Strela anti-aircraft missiles. War supplies such as spare parts, ammunition, trucks and fuel were shipped to North Vietnam in unprecedented quantities.

The North Vietnamese planners thought the initial strikes south of the DMZ— including attacks on Hue and Da Nang, accompanied with pressure on South Vietnamese forces in the A Shau Valley to the west—would force Thieu to send his reserves to protect the northernmost provinces. The second assault, from Cambodia into Binh Long province, northwest of Saigon, would directly threaten the capital city. Then the attack in the Central Highlands would take Kontum and Binh Dinh provinces, splitting South Vietnam in two and potentially causing the collapse of the regime in Saigon.

U.S. forces expected some kind of attack after the first of the year, perhaps during the Tet holiday in February 1972. However, Tet passed quietly. Intelligence indicated that an offensive was still in the making, yet there were few indications that it would involve the largest concentration of communist conventional forces assembled thus far.

In the March 30 attack, the newly formed ARVN 3rd Division assigned to defend Quang Tri was overwhelmed. Many units fled in panic. By April 2, Easter Sunday, the ARVN 56th Regiment and the bulk of the supporting long-range artillery units at Camp Carroll had surrendered to the NVA 308th Division. The rest of the ARVN 3rd Division fell back to the Mieu Giang River, just south of the DMZ.

South Vietnamese marines and several new M48A3 tanks set up a hurried defensive line south of the Cua Viet River at Dong Ha, also near the DMZ. The marines initially held back the North Vietnamese trying to cross a bridge from the north side of the river, but ultimately the order was given to destroy it. U.S. Marine adviser Capt. John Ripley and a group of ARVN engineers blew the bridge, forcing the enemy to cross farther west. The delayed NVA crossing provided some breathing room for the defenders at Quang Tri city, but it was a brief respite. The NVA 304th Division and the attached 203rd Tank Regiment crossed the Mieu Giang River at Cam Lo and continued toward Quang Tri, rolling up the South Vietnamese western flank and pushing eastward toward the coast.

Brig. Gen. Vu Van Giai, the ARVN 3rd Division commander, used what was left of his unit plus reinforcements from a Vietnamese marine brigade and nine ARVN ranger battalions to establish a defensive line paralleling Highway 1 from Dong Ha south to Quang Tri. By April 8, this force had repulsed several attacks, but poor flying weather precluded much-needed air support.

As the ARVN soldiers and Vietnamese marines held on tenuously in the north, the NVA attacked Binh Long province. Following a feint toward Tay Ninh on April 5, the Viet Cong 5th Division, supported by two companies from the 203rd Tank Regiment struck Loc Ninh, 12 miles from the Cambodian border. Defended only by one infantry regiment from the ARVN 5th Division and a squadron from the 1st Armored Regiment, Loc Ninh was quickly surrounded and pummeled by heavy artillery. Despite the efforts of close air support and U.S. Air Force AC-130 Spectre gunships, the city fell the next day, giving the enemy a direct route down Highway 13 through An Loc and Lai Khe to Saigon, just 65 miles south.

After the fall of Loc Ninh, the VC-NVA 5th, 7th and 9th divisions moved south rapidly. Although the 5th and 9th divisions were designated “VC,” they were manned by NVA regulars. The communists quickly overran a two-battalion task force between Loc Ninh and An Loc, then unexplainably paused before moving toward An Loc, which provided time for the city’s defenders to prepare. When the North Vietnamese resumed their advance, they soon surrounded An Loc and blocked Highway 13 south of the city, effectively cutting off the ARVN defenders from ground reinforcement and resupply. Thieu radioed senior ARVN commanders in An Loc that the city would be “defended to the death.”

In the early morning on April 13, NVA gunners began shelling An Loc with mortars, rockets and heavy artillery. Shortly after daybreak, the bombardment was followed by a massive infantry attack supported by T-54 and PT-76 tanks. South Vietnamese forces in An Loc, under the command of the ARVN 5th Division, fought the attackers in close urban combat.

Bell AH-1G Cobra attack helicopters from a reinforced 3rd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) took on the tanks in An Loc. Additional help came from U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marine fighter-bombers, as well as AC-130 gunships. Shored up by air support, the ARVN defenders held their ground against the assault—just barely. They had been pushed into an area less than a square mile. Meanwhile, waves of Air Force B-52 bomber strikes took a heavy toll on the attackers and prevented them from massing all their forces against the defenders.

As the attack in Binh Long province unfolded, the North Vietnamese launched the third prong of their offensive.

In early April, ARVN firebases and outposts north of Kontum in the Central Highlands had come under several probing attacks. In response, B-52s struck suspected staging areas along the Cambodian and Laotian borders. No major attacks in the Highlands materialized, but on April 5 the North Vietnamese struck the two northernmost districts of Binh Dinh province to the east of Kontum province. The defending 40th Regiment of the ARVN 22nd Division fell back in the face of the onslaught.

Lt. Gen. Ngo Dzu, the top ARVN commander in central Vietnam, and his U.S. adviser, civilian John Paul Vann, had a decision to make: Send troops from Kontum to reinforce Binh Dinh or keep them in defense of Kontum. On April 12, while they were trying to decide, the NVA attacked Kontum city with a rocket and artillery barrage.

Then a tank-supported infantry assault by the NVA 320th Division hit outposts stretching from Kontum to Tan Canh, northwest of the city. The defenders from the ARVN 2nd Airborne Brigade and several ranger battalions were in a desperate situation, but B-52 strikes enabled them to hold on against repeated ground attacks.

Elsewhere in the Central Highlands, on April 19, the NVA 2nd Division supported by the 203rd Tank Regiment struck the ARVN 22nd Division at Tan Canh and nearby Dak To. South Vietnam’s U.S.-made M-41 light tanks proved no match for the heavier Soviet-supplied T-54s. When the North Vietnamese sent in reinforcements, both Tan Canh and Dak To fell. The road south to Kontum was clear. The NVA, as at An Loc, did not press its advantage, again for unknown reasons. Kontum’s defenders had time to prepare for the next round.

With most U.S. combat troops already departed, Nixon knew the only major U.S. asset available to meet the North Vietnamese offensive was air power. Formidable numbers of combat aircraft were already stationed in South Vietnam, at bases in Thailand and on carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin. Nixon buttressed those numbers on April 9 when he ordered Operation Constant Guard, which sent the equivalent of 15 squadrons of strike aircraft to South Vietnam. He eventually increased the number of carriers in the South China Sea from two to six, which effectively doubled the availability of close air support aircraft. Nixon also ordered additional B-52s to Guam and Thailand for potential use in Vietnam.

He told Air Force Gen. John W. Vogt, newly appointed commander of the 7th Air Force: “I want you to get down there [Saigon] and use whatever air you need to turn this thing around…stop this offensive.”

This vast air armada pounded the North Vietnamese attackers at An Loc, Kontum and Quang Tri. To stem the flow of reinforcements and supplies to North Vietnamese forces in the South, American aircraft attacked supply lines, logistics facilities and supporting military infrastructure from the DMZ to the 20th parallel, which ruled out strikes on Hanoi and the port at Haiphong, above that line. On April 16, Nixon approved a one-day attack on key logistics nodes in the Hanoi and Haiphong areas.

Even with the additional air support, the situation in northern South Vietnam deteriorated. On April 14, Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, the ARVN commander in that region, ordered Giai, the ARVN 3rd Division commander, to retake Cam Lo, Camp Carroll and Mai Loc, near Camp Carroll, to reestablish a defensive line in the north. The South Vietnamese troops were worn out, and the counterattack was poorly planned and executed. By April 17, it had failed after advancing less than half a mile.

The North Vietnamese continued to hammer Quang Tri from three sides. On April 27, cloud cover again precluded effective close air support, and the NVA 304th Division increased the intensity of its attack. Thousands of South Vietnamese refugees flooded Highway 1, rushing toward Hue. NVA gunners killed many of those fleeing south along what became known as the “Highway of Death.” On May 1, the city of Quang Tri fell. The rest of Quang Tri province came under NVA control two days later. The NVA offensive stalled, and the fighting in northern provinces degenerated into a bloody stalemate.

To the south, the fighting continued at An Loc and Kontum. Concerned about North Vietnamese forces inching closer to Saigon, Thieu ordered the ARVN 21st Division in the Mekong Delta to relieve the besieged defenders in An Loc. By this time, the NVA 7th Division was entrenched across the highway south of the town. The ARVN relief column quickly bogged down. An Loc suffered repeated ground attacks and around-the-clock shelling. The ARVN defenders, reinforced with the South Vietnamese 1st Airborne Brigade and aided by their U.S. advisers and U.S. air power, held their ground against overwhelming odds but suffered heavy casualties. During the battle for An Loc, B-52s flew 252 missions. There were also 9,023 tactical airstrikes, including attacks by AC-130 Spectre gunships.

In the Central Highlands, hard-pressed South Vietnamese forces also held out against the NVA juggernaut. As at An Loc, air power proved to be decisive. During a three-week period, there were 300 B-52 strikes in support of the Central Highlands’ defenders.

With Quang Tri lost and An Loc and Kontum still besieged, Nixon and the Joint Chiefs of Staff removed all restrictions on bombing North Vietnam. On May 8, the president ordered the commencement of Operation Linebacker. In some of the most intense bombing of the entire war, B-52s and fighter-bombers pounded Hanoi and Haiphong. Simultaneously, A-7 Corsair II and A-6 Intruder attack planes from USS Coral Sea dropped into Haiphong Harbor 36 Mark 52 1,000-pound electromagnetic aerial mines—which explode when the hull of a metal ship passes over them—in an attempt to cut off supplies arriving by sea. Additional aircraft dropped mines on the smaller ports of Cam Pha and Hoi Gai north of Haiphong, as well as the river estuaries at Thanh Hoa, Vinh, Qung Khe and Dong Hoi.

At the same time that aircraft were striking the Hanoi-Haiphong area, 7th Air Force commander Vogt initiated what he described as “the most intensive in-country interdiction campaign of the war” against North Vietnamese supply lines and base areas in the south.

The continuous pounding of North Vietnam, the blockade of its major ports and the interdiction campaign hampered the ability of the communist forces in South Vietnam to sustain their offensive. The strengthened air support in the South removed some pressure from the ARVN ground forces. Yet intense fighting persisted throughout summer all over South Vietnam as the NVA continued its ground attacks while pulverizing the defenders with heavy artillery, rockets and mortars. It was clear, however, that the relentless fire of attack helicopters, strike aircraft, AC-130 gunships and B-52s was taking a heavy toll on the North Vietnamese troops. Things began to look up for the South Vietnamese at An Loc and Kontum.

With the situation somewhat stabilized in the central and southern regions, Thieu’s top priority was the lost territory in the northern region. The South Vietnamese president replaced Lam, the commander in the north, with Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong. One of the best ARVN generals, Truong energized his men and began preparing a counteroffensive to retake Quang Tri and other enemy-held positions in that area.

The new offensive, Lam Son 72, began June 28 with a two-pronged assault across the My Chanh River. The South Vietnamese Airborne Division attacked Quang Tri from the south paralleling Highway 1, while the marines, supported by the 1st Ranger Group and the 7th Armored Cavalry, moved northward to strike from the southeast. At the same time, Truong ordered the 1st Division to secure Hue and his rear area while the 2nd Division conducted operations in Quang Tin and Quang Ngai provinces to the south.

Backed with air support, Truong’s forces made slow but steady progress. On July 7, the 2nd Airborne Brigade reached the outskirts of Quang Tri, but the North Vietnamese stiffened their defenses with reinforcements. Truong requested additional air support. U.S. aircraft flew nearly 7,500 sorties in July. Despite heavy casualties from the airstrikes, North Vietnamese soldiers doggedly held the territory they had taken. The battle for Quang Tri and surrounding areas became a bloody slugfest. Covered by massive air support, Truong realigned his forces and directed the marines to make the main attack. By Sept. 16, after several weeks of intense urban fighting, the marines retook the city and raised the South Vietnamese flag over the heavily damaged Quang Tri citadel.

The recapture of Quang Tri effectively signaled the end of the Easter Offensive. The South Vietnamese forces had also prevailed in An Loc and Kontum. Estimates placed North Vietnamese casualties at more than 100,000 killed. North Vietnam also lost at least half of its large-caliber artillery and tanks. South Vietnamese casualties were approximately 10,000 killed and 33,000 wounded. There were 759 Americans killed in Vietnam during the year 1972.

The South Vietnamese celebrated a great victory. They had withstood everything the communists threw against them in some of the heaviest fighting of the war.

That victory, however, was achieved with massive amounts of U.S. air support, and the battles had been close. Many ARVN soldiers had fought valiantly against overwhelming odds, but some South Vietnamese military leaders and units had not done well. In the end, the NVA controlled more territory in South Vietnam than before, and Hanoi believed itself in a stronger position at the Paris negotiations.

In a TV address on April 26, well before the outcome was certain, Nixon had forecast that when the fighting was over “the South Vietnamese will then have demonstrated their ability to defend themselves on the ground against future enemy attacks.” He added, “Vietnamization has proved itself sufficiently that we can continue our program of withdrawing American forces without detriment to our overall goal of ensuring South Vietnam’s survival as an independent country.” He announced that over the next two months 20,000 more American troops would be withdrawn.

The South Vietnamese victory became one of the rationales for complete U.S. withdrawal and Nixon’s “peace with honor.” The Paris negotiations produced an agreement for ending the war in January 1973. On March 29, 1973, MACV cased its colors, and the last American troops departed South Vietnam. Nixon promised Thieu that the United States would support South Vietnam if Hanoi launched new offensives.

The South Vietnamese fought on alone, performing well in 1973 in renewed fighting. By the end of 1974, however, the North Vietnamese had rebuilt their forces in the South. As the North Vietnamese became stronger, the South Vietnamese became weaker, lacking the support promised by Nixon, forced to resign in August 1974 during the Watergate scandal. When the NVA launched an offensive the next spring, South Vietnamese forces succumbed in 55 days. Saigon surrendered unconditionally on April 30, 1975.

James H. Willbanks is a retired Army lieutenant colonel and decorated Vietnam veteran. He is the author or editor of 21 books on the Vietnam War and other aspects of military history. During the 1972 Easter Offensive, Willbanks, then a captain, was an adviser with a South Vietnamese infantry unit at An Loc. He lives in Georgetown, Texas.

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.