On Halloween night in 1966, Petty Officer 1st Class James Elliott “Willy” Williams, commanding a two-boat patrol using craft specially designed for combat on Vietnam’s inland waterways, was gunning for enemy vessels infesting the Mekong Delta. Williams in Patrol Boat River 105 destroyed one of two Viet Cong sampans spotted on the My Tho River. Pursuing the second down a narrow canal, PBR 105 and PBR 99 surprised two VC regiments just beginning to move downriver in sampans and junks.

Williams ordered his small fiberglass boats, introduced in Vietnam just eight months earlier, forward in attack formation. With guns blazing from both sides, the PBRs struck with bows high above the water, slicing through the enemy flotilla at full-throttle, twisting and turning to present a poor target—their wakes washing over and capsizing the sampans. VC in fortified riverbank positions countered with mortar shells, rockets and small-arms fire but were unable to accurately aim their weapons at Williams’ fast-moving boats.

The U.S. patrol encountered additional junks and larger VC formations farther down the canal. Crews on the two speedy PBRs released thunderous fire on a stunned enemy flotilla. Soon the Navy’s Huey helicopter gunships arrived. Williams’ boats made another run down the canal.

Ordering searchlights turned on as dusk approached, Williams pressed the attack into the night. The crews of PBRs 105 and 99 destroyed 65 VC vessels and inflicted an estimated 1,000 casualties, while suffering little if any damage to their own craft. For his actions that Halloween night, Williams received the Medal of Honor.

An ocean away, another man shared in the success that Williams and his men achieved in those fast, highly maneuverable, well-armed PBRs. His company’s name was engraved on each boat’s brass builders plate: “United Boat Builders Inc., Bellingham, Washington.”

When 35-year-old Arthur “Art” Nordtvedt founded United Boat Builders in 1957, he created a diversified product line of pleasure craft, commercial vessels and military designs to ensure year-round production of his fiberglass boats. United rose to national prominence when it was chosen to produce the Patrol Boat River, manufactured in two versions, the Mark I and Mark II, for the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War.

By war’s end, about 300 of the highly regarded riverine patrol boats had seen action in the Mekong River Delta.

In an interview as United was beginning operations, Nordtvedt said: “We’re just a young bunch of guys banded together, doing the thing we love and enjoy—boatbuilding. I can assure you of this: we have the ability, desire and know-how to succeed.” And succeed they did. By 1960, United had outgrown its startup location in a small leased building and moved to a 100,000-square-foot factory on Bellingham’s waterfront. Once his commercial and pleasure boat lines were in production, Nordtvedt concentrated on military contracts, turning United into a major supplier of fiberglass boats for the Navy.

Ultimately, the company produced more than 2,729 vessels of various types for the government. The first contracts were awarded in December 1961 for 10 Landing Craft Swimmer Reconnaissance support boats. The 52-foot LCSRs were used by the Navy to deploy and retrieve frogmen on missions.

Studies and reports in the early 1960s highlighted the growing use of South Vietnam’s waterways by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army for ambushes, supply shipments and other activities. Of most concern were the tributaries and canal systems of the vast Mekong River Delta, an area of 16,000 square miles, comprising nearly 5,000 miles of waterway. Control of the Delta was crucial to South Vietnam’s commerce.

VC forces had nearly overrun the Mekong, which was becoming a potential NVA incursion route. Countering that threat was an inferior South Vietnamese riverine force that was a mix of vessels abandoned by the country’s former French rulers, possibly a few vessels from the World War II Japanese occupation and junks. The remnants of the 1946-54 French-Indochina War were heavy (thus requiring several feet of water), slow-moving, easily snagged in underwater debris and more lightly armed than their VC opponents.

In January 1965, the Weapons Planning Group of the Naval Ordnance Station at China Lake, California, released a report that called for the development of a more effective riverine warfare force. The report emphasized the need for a boat that could operate in a hostile jungle environment with narrow and shallow estuaries full of obstacles, while fighting enemy hidden within fortified bunkers along the Mekong’s waterways.

After reviewing the report, the Navy’s Ordnance Department of the Unconventional Warfare Office issued a set of requirements for a shallow-water hull made of aluminum or fiberglass with a propulsion system that wouldn’t be hindered be the weeds common in the Delta. Speed and maneuverability were also essential. The urgent need meant there was no time to design a craft from the keel up, suggesting an existing hull design would have to be adapted for military use.

Nordtvedt’s United Boat Builders was hardly the only company interested in the lucrative Navy contract. Major competitor Hatteras Yacht Co. of North Carolina also was eyeing the prize. In 1965 Hatteras founder Willis Slane and his naval architect, Jack Hargrave, were invited to Washington, D.C., with other vessel manufacturers. A captain in the Ordnance Department was said to be making a desperate plea for a shallow-water craft in the 30-foot range, based on an existing hull, that could run up to 30 knots (35 mph) and be adapted for operations in Southeast Asia.

Architect Hargrave reportedly turned to Slane during the meeting and said his design team could meet those specifications with Hatteras’ existing 28-foot sporting hull. According to Hargrave years later, Slane stood and said, “Excuse me captain, I have just put into production a very fast, broad-beamed hull, 28 feet long, that might do the job.” Getting everyone’s attention, Slane continued: “If we could drive her with water-jet pumps, we wouldn’t have to contend with shafts, propellers and rudders. That would allow high-speed operation in very shallow water.” The captain asked how long it would take to get a formal proposal from Hatteras. Slane responded: “Proposal, hell! I haven’t time for that paperwork stuff. I’ll build the damn boat.”

Returning to North Carolina, Slane took two 28-foot hulls and equipped them with a water-jet drive from Indiana Gear Works and a set of supercharged Daytona diesel engines. A week later, a prototype was in the water, running at 30.5 knots. Slane was ready to demonstrate his creation to the Navy. Tommy Henshaw, a longtime Hatteras employee, recalled: “I had a chance to ride on it. Slane tested that boat to the limit. It was fast. It would turn and stop on a dime.”

As Slane developed his prototype, word of his negotiations with the Navy reached Nordtvedt some 3,000 miles away. “I had heard through [informal] channels in the industry that Willis Slane was dealing with the Ordnance Department to develop a river patrol boat for use in Vietnam,” Nordtvedt recalled in an interview with this article’s author. “I wondered why the Bureau of Ships’ small boat division wasn’t involved at the procurement level, where a circular of requirements and contracts should originate. I knew Fred Joest at the bureau, so I called to inquire what he knew about this.”

Joest, who would later head the small boat division, oversaw the procurement of more than 5,000 vessels up to 85 feet in length and was responsible for purchasing, bids, designing, construction and maintenance. When Nordtvedt called, a mystified Joest said he would look into the matter.

“Someone at the Unconventional Warfare Office talked with the people at Hatteras about a quick prototype to sell to the Navy,” Joest, also interviewed by this article’s author, reported back to Nordtvedt. “Why they went to Willis Slane, I have no idea. This was not proper procedure.” He told Nordtvedt, “This contract has to go out to bid,” and promised to get a project-bid circular to bidders as soon as possible.

“There was a great need for a large quantity of river boats,” Joest recalled. “They were asking for 120 boats with a three-month turnaround once awarded. I was given a photograph of Slane’s boat and a single sheet of specifications that the Ordnance Department had written. I needed those specs, which bonded bidders to a mandated speed with full armament load.”

Joest didn’t expect many bidders because companies weren’t allowed time to build a mold and would have to meet the requirements with an exiting hull. “We gave them only a week to respond,” he said.

Meanwhile, Nordtvedt had a 30-day lead over his competitors and made the best of his time. “I knew Hatteras was attempting to use their 28-foot hull,” he said. “So, I started with the requirements that the Ordnance Department had given him. I drew my outline on a drawing board in two days and did a lot of experiments on our 31-foot fiberglass sports-cruiser hull.”

Nordtvedt made some changes to accommodate the Navy’s requirements, including the ability to haul extra weight. “The new hull was an improvement over the original, and the design was passed on to the pleasure boat,” he said. “The prototype was soon in the water as we began speed and handling characteristics.”

Although Hatteras was using jet pumps from Indiana Gear Works, Nordtvedt didn’t think those jet pumps were powerful enough. “I started tests on the water-jet propulsion units by Jacuzzi Brothers,” he said. The boat builder also said he could “guarantee 14,000 pounds” for weight.

Besides United and Hatteras, other bidders were Bertram Yacht Co., Boston Whaler, Chris-Craft and Bay Shipbuilding. “We evaluated those bids as the proposals came in,” Joest remembers. “We looked to see who could provide the best performance and where others would fall short. Then we looked at the price. When we saw the United package, we said, this is where we want to go.”

Steve Nordtvedt, Art’s son, was United’s naval contract manager and remembers a proposal error by the company that underpriced the maintenance spare parts kits, which included an engine, water jet and miscellaneous equipment. The cost of each kit was about $11,000. There was one set for every 10 boats, which meant 12 sets for 120 boats.

In the proposal, “I mistakenly included only one set, instead of 12,” the younger Nordtvedt said. “The error was discovered after the proposal was delivered. It was a $120,000 problem. Art phoned Fred Joest.” The Navy contracts official wanted to know if United could swallow the $120,000 rather than add that amount to its bid. “Can you live with that? Joest asked, according to Steve Nordtvedt, and followed with “Don’t raise the issue.” Translation: Don’t make a fuss over $120,000.

Art replied, “We’ll live with it,” as his son recalled. “Fred’s advice was interpreted as a good sign that United was in the running for the contract.”

Hatteras also presented a working prototype, Joest said, but Slane had demonstrated only an empty hull. Navy officials were impressed with its speed and ability to operate in shallow water; however, they were observing a boat with no weight on it, let alone a combat load. Another strike against Slane was his objection to government oversight. The Navy wanted government inspectors in the plant to monitor construction of the boats, said Henshaw, the former Hatteras employee. “Willis told them he’d be glad to build them, but he wouldn’t have the government tell him how to do it. So, we lost the whole contract.”

United Boat Builders submitted the low bid at $75,000 per boat and was officially awarded the PBR contract on Nov. 29,1965. We’ll never know if Slane intended to protest the contract decision. A few weeks earlier, on Nov. 7, 1965, he died of a heart attack.

The PBR contract was the most important project that United ever bid on. The Defense Department made acquisition of the boats a priority. United created four additional one-piece hull and deck molds to meet production demands.

By Dec. 21, the company had built 10 boats, and others were under construction. The tightly drawn contract gave United until April 1 to deliver 120 PBRs. A completed boat was expected to be ready for acceptance trials every eight days.

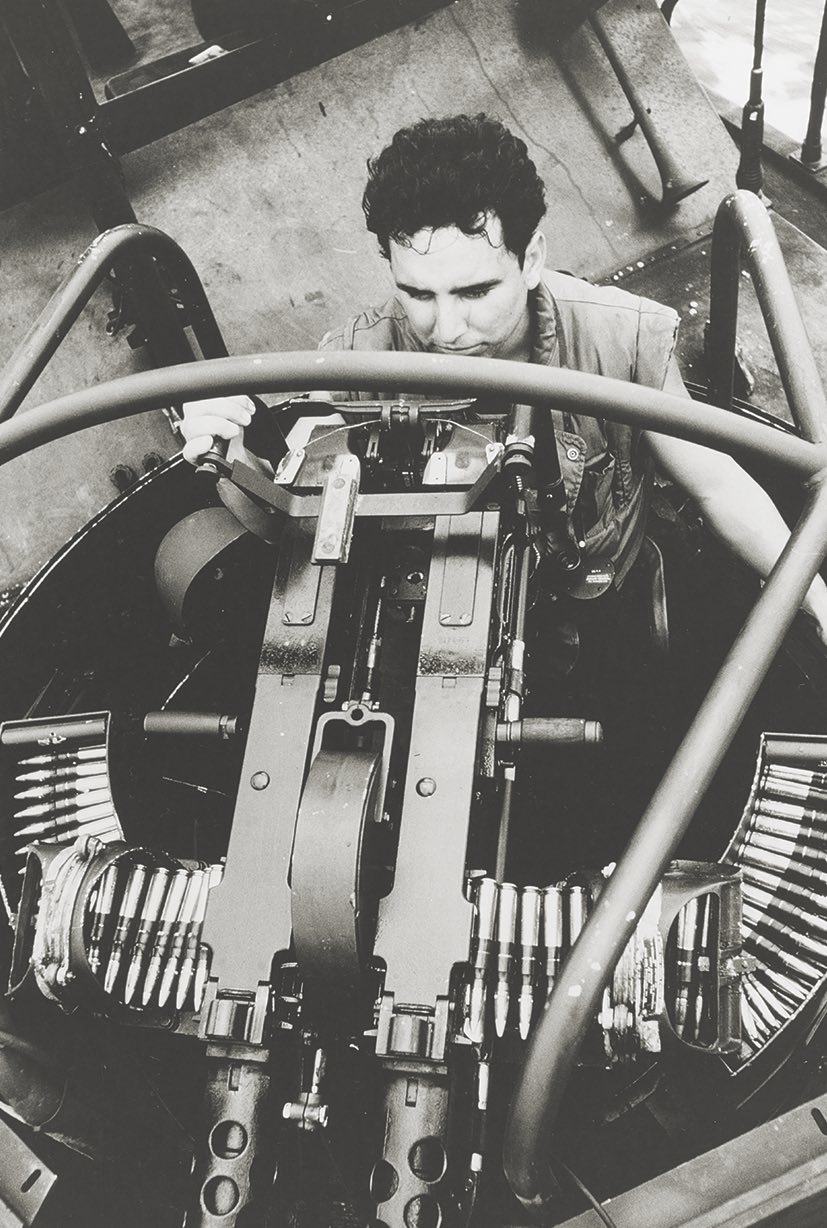

The original PBR Mark I was an olive drab 31-foot craft based on United’s Uniflite sport-cruiser design. There were twin .50-caliber machine guns in a forward M36 turret rotating tub and a fixed .30-caliber M1919AH Browning machine gun on the stern. The boat’s helm featured a windscreen with a soft top canvas. The station for the coxswain (the sailor at the wheel) on the portside had two AN/VRC-46 mobile communications radios and a control panel. A Raytheon 1900N radar set was mounted topside. The coxswain’s station, engines and gun mounts had ceramic armor that could stop small-arms fire.

Installed tightly beneath the deck were two General Motors Detroit Diesel 220 horsepower 6V53N engines with no gearbox, as there was no reverse nor propeller. Instead, the engines drove Jacuzzi 14 WJ water-jet pumps. The pumps were mounted with their intake pipe running through the bottom of the boat and out an opening in the stern. Water would be sucked up the line and passed through an impeller (a small reverse propeller) that accelerated the flow and forced the water out creating a jet steam that moved the boat with a thrust 6,000 gallons a minute.

Rerouting the water 180 degrees stopped the craft quickly, within two boat lengths, giving the PBR exceptional maneuverability. Additionally, with no propeller to foul and drafting about 9 inches (sitting with only 9 inches of the hull under water), the boat could run in very shallow water—virtually anywhere—at high speed.

The first boat off the line was delivered to Hunters Point, San Francisco Bay Naval Shipyard for underwater shock tests to evaluate the fiberglass hull’s integrity. The only changes required were minor modifications to the engine mounts. Nordtvedt, however, was concerned about the boats’ ability to meet United’s performance standard of 25 knots (29 mph) with a full load.

Pre-award experiments performed by United were based on a maximum weight of 14,000 pounds. However, change orders had increased the weight by more than 1,000 pounds. There was also a 500-pound increase in engine weight and heavier new laminates used since the prototype was built. As a result, “we had a 16,000-pound vessel,” Nordtvedt said, “and it took some work to get this thing running properly.”

Joest, assigned to United during the patrol boat program, worked alongside Nordtvedt to find a solution. The first attempt to increase speed involved experiments with the Jacuzzi pumps. That effort failed. “So, we went on a weight witch hunt,” Joest remembered. “We went through the boat piece by piece.”

The original steel mounting ring for the .50-caliber machine gun was remanufactured in aluminum. Diesel heat exchangers were replaced with lighter units. Resin content control was instituted, and boat armor was reduced. Any weight savings not affecting structural integrity were altered until Nordtvedt was satisfied. The result was a vessel displacing 14,600 pounds.

On Dec. 18, 1965, the Navy established Operation Game Warden, which would pool groups of PBRs together as Task Force 116 to patrol the Mekong Delta and disrupt Viet Cong activities. American sailors would board and search vessels for hidden contraband and battle any VC or North Vietnamese forces they encountered.

By mid-January 1966, the first 10 boats passed acceptance trials and were delivered to Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California, north of San Francisco, where the first crews would train to operate them. Subsequent boats were sent direct to Vietnam.

Not all of the boats were delivered on time, Steve Nordtvedt said. There was a penalty of $500 per boat per day for every PBR not delivered by April 1. “The Navy received the 120th boat in mid-April,” Nordtvedt said. “United paid a penalty of $35,000.”

Even though United had not met all the delivery dates, the Navy was nonetheless impressed. An amendment to the original contract called for an additional 40 boats.

The first 11 boats arrived at the Navy’s Nha Be base in Saigon on March 21, 1966. New crews learned to operate the boats in the Vung Tau area, a port location at the tip of South Vietnam. Boat crews were noted for the modifications they made to increase performance. They added armaments and protective shielding. They also tweaked the engines to get more power. Additionally, “crews would modify their gun tubs to hold more rounds,” recalled Petty Officer 3rd Class machinist mate Ralph Christopher, author of Duty Honor Sacrifice. For example, one of his friends, Warrant Officer Ralph Fries, changed the amount for the forward twin .50-caliber machine guns from 250 to 500 rounds per tray. Additionally, “they belted 1,500 rounds per .50 gun and flanked them on each side of the bow and over the pump covers,” Christopher said.

The extra firepower and shielding, however, slowed the boats, which made them vulnerable to ambush. Most crews discovered their greatest weapons were speed and maneuverability in exiting a kill zone, “hot-dogging” from harm’s way, then hitting back. Several months before Williams’ Halloween battle, he ordered all of PBR 105’s armor removed, aside from that protecting his engines. He claimed an increase in speed up to 35 knots (40 mph). The fiberglass hull varied in thickness up to a half-inch. Unless a rocket-propelled grenade or small-arms fire hit the engines or something equally solid, most projectiles would pass through the hull.

Although the Mark I operated with much success, a modified version was soon requested. The Mark II evolved from suggestions by boat crews and observations of the Mark I’s performance after months of intensive use in a harsh, hot and humid environment. The Jacuzzis needed adjustments due to extreme wear. The concerns were such that in September 1966, the Navy flew Nordtvedt, Joest and Jacuzzi Brothers’ Vice President Ray Horan to South Vietnam to observe and evaluate the PBR’s progress.

The new boats had a flatter hull, greater width and increased length. “Art’s Mark I had a ‘deep-Vee’ [hull] design, which was commonly used in rougher coastal waters,” Joest said. “We’re talking riverine waters now.”

Steve Nordtvedt believed the new boats were more suited for their intended purpose. The Mark II’s main advantage was “its ability to carry a heavier load with no loss in performance,” he said. “The weight required in combat quickly outgrew the Mark I’s ability.”

The Mark II enabled crews to add more armament, most commonly two 7.62 mm M60 machine guns and a 40 mm grenade launcher. Some crews maximized their firepower by adding a 20 mm cannon forward or placing an 81 mm mortar toward the stern. The new PBR was a formable war machine. Art Nordtvedt wasn’t impressed by the redesign, claiming his original boat was a better concept. Changes “made the hull stiffer and less flexible,” he said.

United Boat Builders’ PBR wartime program ran from December 1965 through September 1975, with 161 Mark I and 355 Mark II boats completed. At the end of production in 1977 a total of 535 PBRs had been manufactured. Many went to foreign navies.

Nordtvedt refused to take sole credit for designing and building the boats that had so nimbly borne their crews in and out of harm’s way. Each time he was thanked, he would respond, “It’s my crew you want to thank, not me.” Nordtvedt died on Oct. 1, 2013, at age 91. V

Todd Warger is a recipient of the Washington State Historical Society’s 2008 David Douglas award for the documentary film Shipyard. He conducted about 20 recorded interviews with Art Nordtvedt in 2006. Warger resides in Bellingham, Washington.

This article appeared in the December 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.