*Note: Since Pauli Murray lived in a gender-binary world, this article follows the historical precedent of using she/her pronouns.

As a teenager in 1920s Durham, North Carolina, Pauli Murray strode each May across the Whites-only cemetery where a sea of Confederate flags marked the graves of Civil War veterans. She climbed over a fence to enter her family burial ground and defiantly planted a U.S. flag where her grandfather Robert Fitzgerald rested. “Upon this lone flag, I hung my nativity and the right to claim my heritage,” Murray later wrote. “It bore mute testimony to the irrefutable fact that I was an American and it helped to negate in my mind the signs and symbols of inferiority and apartness.”

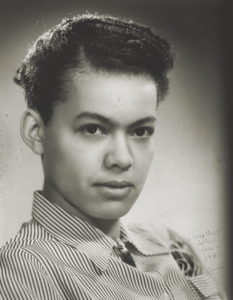

Pauli Murray was a key mid-20th century American figure who linked the legal equity crusades of the civil rights and feminist movements. Along the way, searching for self and soul, she navigated settings in which people of color or women were unwelcome and poor people were scarce. Her skin looked too dark to some, to others too light; she didn’t feel female but didn’t appear male. She was drawn to social activism but also loved to write poetry and to research law briefs. Her private struggle to reconcile her gender identity and public persona is only beginning to be understood.

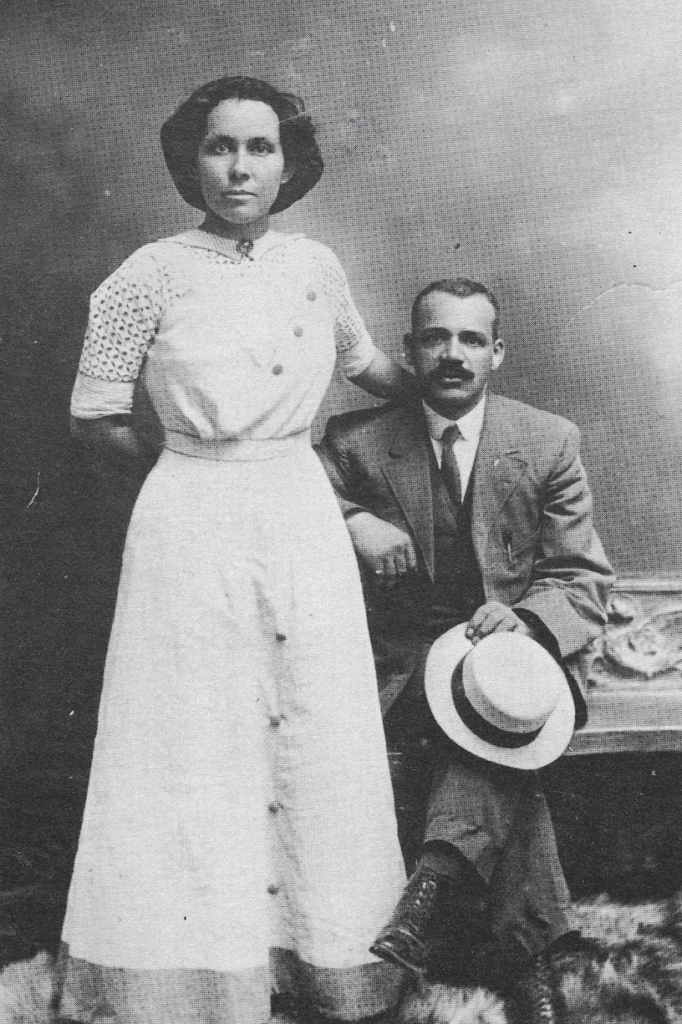

Her challenges began early. Born Anna Pauline Murray in 1910 to a biracial family in Baltimore, Maryland, she lost both parents young. Local relatives took in her siblings; she grew up with her maternal grandparents and aunt in segregated Durham. With white and black forebears on both sides of the family, her Carolina kin lived in a precarious social situation.

“The world revolved on color and variations in color,” Murray wrote. Grandfather Fitzgerald, born free in Pennsylvania, settled in Durham after his Civil War service, teaching freed people and helping them claim new lives. Grandmother Smith was the issue of a rape by a prominent local White politician; her desire to claim her rightful social status clashed with the color line. Both grandparents died during Murray’s youth. Her aunt was an educator with no option except the pitiful salaries African American teachers earned at underfunded Black schools. Murray grew up reading classic texts to her grandfather and absorbing Aunt Pauline’s tutoring. Her aunt recognized something distinctive in her niece, whose nickname was Paul; Pauline called her “my little boy-girl.”

“Paul” intensely hated segregation. She bicycled rather than ride public transportation relegating “colored” people to the back of the bus. She refused to enter the segregated movie theater. The high school she attended did go to the 11th grade; Durham’s other Black secondary schools ended at 10th grade. She edited the school paper, joined the debating team, and played basketball, earning money selling and delivering newspapers, serving as a gofer at the local Black newspaper, and typing for a Black-owned insurance firm. In 1926 “Paul,” 15, graduated first in her class of 40, sights set on New York City, where, in the course of visiting relatives, she had glimpsed a different world.

In New York, the eager graduate discovered the limits of her segregated education. She needed three or four more semesters of study to get into college. Rather than pay to take remedial classes, she stayed with relatives in Queens and enrolled at Richmond Hill High, the only Black among 4,000 pupils. She completed the necessary coursework within a year.

Color was not the only hallmark of segregation, as Murray discovered when she applied to her first college choice. Columbia University did not admit women—and would not until 1983. It was small consolation that she could attend Barnard, Columbia’s affiliated college for women; on her own financially, she adapted. In fall 1928, Murray matriculated at Hunter College, a publicly funded tuition-free institution for women that admitted students of all races, creeds, and ethnicities. In her later years, she acknowledged the compensations of attending a female-only school. “[T]he school was a natural training ground for feminism,” she wrote. “Having a faculty and student body in which women assumed leadership reinforced our egalitarian values, inspired our confidence in the competence of women generally, and encouraged our resistance to subordinate roles.”

In college, Murray built the foundation of her intellectual development. She was quick to make friends and found encouraging English and political science professors. After one semester, she moved into the Harlem YWCA, luxuriating in the majority-Black environment. The Y offered a front-row seat to the Harlem Renaissance, often presenting Black notables—writers, civil rights leaders, and political figures like Langston Hughes, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Paul Robeson. Murray interacted regularly with people like Dorothy Height, a Y staffer who later led the National Council of Negro Women, and Ella Baker, a neighborhood regular, later a notable civil rights organizer. Murray refashioned her name as “Pauli” and began imagining a writing career.

Markers of inferior status persisted. Help-wanted ads wanted “whites only;” stopping at a soda fountain with White friends, Murray might not be served. An American history professor’s handling of Reconstruction so alarmed her that she embraced activism, spearheading an effort to create a student group devoted to the study of Negro history and culture.

The 1929 onset of the Depression complicated Murray’s marginal economic situation. When she lost her primary job as a waitress, she dropped out of Hunter. She ate less and struggled emotionally. She managed to return to Hunter and graduated in January 1933 with an English major and dim prospects. That fall, she secured full-time employment as a traveling representative for the National Urban League journal Opportunity; the resulting year of constant travel damaged her health. Her doctor urged rest at a sanitarium; an alternative yielded a surprising connection.

Camp Tera (“Temporary Emergency Relief Assistance”), in the Catskill Mountains of New York, was among the earliest of 90 New Deal sites offering women vocational training, healthy living, and community. The system came to be after Eleanor Roosevelt pushed her husband the president to help jobless women. Participants got room, board, and a $5 monthly stipend. A resident wrote, “It’s not only that I am getting enough to eat for the first time in three years, but I am beginning to think of myself as a real person again.” Pauli Murray thrived at camp and her health improved.

Nonetheless, when Mrs. Roosevelt visited Camp Tera in spring 1934, Murray felt a need to protest. She appreciated the First Lady’s efforts to establish the facility but felt the Democratic Party still was marching to the tune called by its powerful Southern wing. As Eleanor Roosevelt was crossing the dining hall, everyone but Murray stood. The First Lady took little notice, but the camp director called Murray on the carpet. She declared her right to remain seated and noted that she had washed and donned clean clothing out of respect for Mrs. Roosevelt.

Murray spent the next few years working mostly as a teacher for the Workers’ Education Project of the Works Progress Administration. Many of her co-workers, who included Ella Baker, believed in socialism or communism. Murray began studying to deepen her grasp of labor and radical history, even briefly joining a communist group. She was arrested while picketing the offices of a Harlem newspaper alongside locked-out union members and felt relieved when a judge dismissed those charges. She wrote poems and articles, some of which were published. She was coming into her own. Her desire to work at dismantling Jim Crow drew her to consider attending law school, prompting her to attempt to integrate the University of North Carolina in 1938.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had spoken at UNC and praised the university’s progressive policies, embodied in its president’s decisions to shield leftist faculty and publicly criticize fascism and Jim Crow. Murray boldly wrote to FDR, pressing him to stand against bias and call for UNC and other schools to admit Black students. Doubting the president would see her letter, Murray sent a copy to the First Lady with a personal note. “You do not remember me, but I was the girl who did not stand up when you passed through the Social Hall at Camp Tera,” she wrote. “I thought and still feel that you are the sort of person who prefers to be accepted as a human being and not as a paragon.” Mrs. Roosevelt replied. “I understand perfectly, but great changes come slowly,” she wrote. “Sometimes it is better to fight hard with conciliatory methods.”

That exchange began a friendship that lasted until Eleanor Roosevelt’s death. The two regularly corresponded about civil rights issues and Mrs. Roosevelt sometimes invited Murray to tea. Murray was far more militant than the First Lady, but Mrs. Roosevelt thrived on such relationships, often drawing on them as she advised the president and made her own way in politics. Murray later wrote that the First Lady “gave me a sense of personal worth.”

Pauli Murray applied to UNC graduate school about the time that the NAACP won a Supreme Court decision ordering the University of Missouri’s law school to admit a Black applicant. When UNC quickly rejected Murray’s, she alerted the NAACP. She had support from the UNC president and some faculty and students, but her arrest record and radical ties made her too risky a symbolic defendant. NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall declined to take the case but did recommend her to his alma mater, Howard University School of Law, a fount of legal expertise for the NAACP.

In fall 1941, Murray matriculated at Howard School of Law in Washington, DC. Part of an historically Black institution founded after the Civil War, Howard Law had produced the first Black female lawyer, Charlotte E. Ray. Even so, in her time at Howard Pauli Murray was the only woman in her class; women then comprised less than 1 percent of American law students. As she wrote later, her years at Howard broadened and deepened her perspective. “The racial factor was removed in the intimate environment of a Negro law school dominated by men, and the factor of gender was fully exposed,” she wrote. Murray soon coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the multiple layers of bias facing women of color, what some now call “intersectionality.” She honed this concept for more than 20 years. While in DC, she also joined the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), helping organize and participating in demonstrations.

She indirectly played a role in the strategizing that produced the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education. In 1944, her third-year civil rights seminar was brainstorming legal strategies to combat the “separate but equal” precedent imposed in 1896 by Plessy v. Ferguson. Murray wondered, instead of the current approach—showing that facilities were unequal—why not attack the very constitutionality of segregation, that is, focus on “separate”? Her classmates stared, then erupted in derisive laughter at such an outlandish thought. Murray doubled down: she bet $10 that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years.

Her final seminar paper developed the idea that citizen rights included “the right not to be set aside or marked with a badge of inferiority.” Drawing on psychological and sociological studies as well as her personal history, she argued that segregation did “violence to the personality of the individual affected, whether he is white or black.”

A decade later, NAACP lawyers working on what became Brown read her paper; Murray’s argument became integral to their Supreme Court presentation. Chief Justice Earl Warren’s Brown opinion for the majority declared that separating students by race “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” Murray won her bet.

Pauli Murray achieved academic success through sheer will despite experiencing increasing psychological conflict, rooted, she believed, in gender. She was what today is considered a type of transgender: she appeared female but intensely felt herself male. She rejected the idea that she was homosexual: she was attracted to heterosexual women. No glandular disorder was found. She pursued hormone treatments, then experimental in the U.S. for men deemed effeminate; no doctor she found would agree to perform the procedure. She finally had her abdomen x-rayed, believing it would reveal the existence of male organs. However, her reproductive organs seemed normal. Physicians she consulted, though sympathetic, believed her conflict to be purely psychological.

Murray graduated at the top of Howard Law’s class of 1944. She received the prestigious Rosenwald Fellowship, usually a ticket to study at Harvard. But even with a recommendation from President Roosevelt Harvard did not admit women. Murray decamped to the University of California Berkeley to pursue a master’s degree. She briefly became that state’s first African American Deputy Attorney General, a post she lost when Japan’s surrender ended World War II and American veterans reclaimed their jobs. However, her poems and articles on civil rights were gaining recognition. The National Council of Negro Women named her one of 12 “Women of the Year” for 1945; a year later, Mademoiselle magazine did likewise.

Returning to New York, Murray found work alongside a prominent Black attorney. In 1948, the Women’s Division of the Methodist Church offered her a groundbreaking opportunity. That group had spent decades campaigning against lynching and racial discrimination. To encourage more systemic action, the Division consulted Murray about compiling a reference work on southern segregation laws. Murray suggested that a nationwide study comparing segregation with anti-discrimination laws would serve their purpose better. The Methodists agreed.

The book-length States’ Laws on Race and Color, published in 1951, became a milestone in civil rights and significantly raised Pauli Murray’s profile. The ACLU bought 1,000 copies to send to law libraries and human rights groups. Thurgood Marshall gave every litigator on his NAACP staff a copy and hailed Murray’s volume as that office’s new “bible.” The book’s impact was short-lived only because of rapid legal changes in the wake of Brown.

The notion that a person is either male or female is endemic to Western culture, though some South Asian cultures, the Maori of New Zealand, and some Native American tribes have long accepted three or four genders. The German Magnus Hirschfeld was the first documented physician to consider sex change a legitimate part of health care. As early as 1918, Hirschfeld was using the now-obsolete word transvestite and offering patients hormone therapy and/or sex change operations. The 2015 film The Danish Girl fictionalized one of Hirschfeld’s cases. As a result of his mid-century studies, American biologist Alfred Kinsey imagined gender as a continuum, coining the term transsexual. Many Americans learned about sex reassignment when the story of Christine Jorgensen, reassigned from male to female, appeared in New York City newspapers in December 1952. New York endocrinologist and Hirschfeld student Henry Benjamin’s 1966 book The Transsexual Phenomenon became a milestone in health care, laying out treatment options and rejecting the notion that patients like Pauli Murray needed a cure. Use of the current designation transgender preceded Benjamin’s, appearing in the 1965 textbook Sexual Hygiene and Pathology, by John F. Olivan. These days transgender or trans is a category encompassing a range of identities including transsexuals and cross-dressers. —J.D. Zahniser

The notion that a person is either male or female is endemic to Western culture, though some South Asian cultures, the Maori of New Zealand, and some Native American tribes have long accepted three or four genders. The German Magnus Hirschfeld was the first documented physician to consider sex change a legitimate part of health care. As early as 1918, Hirschfeld was using the now-obsolete word transvestite and offering patients hormone therapy and/or sex change operations. The 2015 film The Danish Girl fictionalized one of Hirschfeld’s cases. As a result of his mid-century studies, American biologist Alfred Kinsey imagined gender as a continuum, coining the term transsexual. Many Americans learned about sex reassignment when the story of Christine Jorgensen, reassigned from male to female, appeared in New York City newspapers in December 1952. New York endocrinologist and Hirschfeld student Henry Benjamin’s 1966 book The Transsexual Phenomenon became a milestone in health care, laying out treatment options and rejecting the notion that patients like Pauli Murray needed a cure. Use of the current designation transgender preceded Benjamin’s, appearing in the 1965 textbook Sexual Hygiene and Pathology, by John F. Olivan. These days transgender or trans is a category encompassing a range of identities including transsexuals and cross-dressers. —J.D. Zahniser

Sex=Biological characteristics

Gender=Social roles/behavior/expectations

Murray likely considered sex reassignment in 1952, when Christine Jorgensen’s reassignment surgery made headlines. In 1954, doctors identified and treated a thyroid disorder as the root of many of Murray’s health issues, including anxiety and depression. She later wrote, “I finally settled down to the first [mental] stability I had known.” She did not waver in her attitude about her gender but did not pursue hormone treatments or sex reassignment. She may have feared the professional cost of taking a step so extreme in society’s eyes. Few people even knew of her predicament.

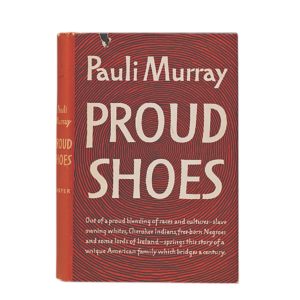

Murray found a publisher for a memoir of her youth in Durham. Proud Shoes came out in October 1956 to praise in The New York Times, the Herald Tribune, and the New York Post, as well as in Mrs. Roosevelt’s widely syndicated “My Day” column. Two decades later, after success greeted Alex Haley’s Roots, Murray recalled a sentence in Proud Shoes: “It had taken me almost a lifetime to discover that true emancipation lies . . . in deriving strength from all my roots, in facing up to the degradation as well as the dignity of my ancestors.”

Shortly after her memoir debuted, Murray was recruited by Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison, a law firm noted in the 1940s for having been the first to hire a female partner and later a Black associate. The Garrison at the firm was Lloyd, great-grandson of White abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and an acquaintance of Murray’s from events at Howard Law. During her three years at Paul, Weiss, she met the woman who would be her closest companion for nearly 20 years; Irene Barlow worked as the firm’s office administrator. Though White and British by birth, Irene bonded with Pauli over their poverty-stricken early years. A spiritual bond developed from their shared Episcopalian faith. Among the women Murray met at the firm was an intern named Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

In April 1962, Eleanor Roosevelt asked Murray to join a Committee on Civil and Political Rights, part of the first President’s Commission on the Status of Women. Murray was completing a doctorate in law at Yale, meanwhile mentoring younger students like Eleanor Holmes and Marion Wright, now better known by their married names, Norton and Edelman. Murray continued on the pioneering committee after Mrs. Roosevelt’s death six months later. Her work with the Commission led to organizing with women newly focused on sex discrimination. In 1965, Murray’s network prevailed upon Congressional contacts to ensure that the word “sex” stayed put in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act as that legislation moved through Congress, a small addition that promised big dividends. Later that year, Dr. Murray proposed another trailblazing legal strategy. She developed a memo originally written for the President’s Commission into “Jane Crow and the Law.” An article co-authored with Commission staff attorney Mary O. Eastwood, “Jane Crow” advocated using the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause against sex discrimination. In 1971, Rutgers law professor Ruth Bader Ginsberg wrote the ACLU legal brief for Reed v. Reed using this novel argument. In the resulting landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled sex discrimination unconstitutional under the equal protection clause. Ginsberg acknowledged her intellectual debt by naming both Murray and Eastwood co-authors of her brief.

Pauli Murray continued working with policy-minded feminists. In an October 1965 speech before the National Council of Women, she called Title VII an historic victory that “will not be adequately enforced unless the political power of women is brought to bear.” Word of Murray’s call to arms prompted a phone call from Betty Friedan, by that time widely known for her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Friedan was persuaded to join Murray and two dozen other Black and White feminists in founding the National Organization for Women (NOW) on June 30, 1966. Friedan and Murray wrote NOW’s statement of purpose, with Murray contributing, “We realize that women’s problems are linked to many broader questions of social justice.” She hoped NOW would be an NAACP for women.

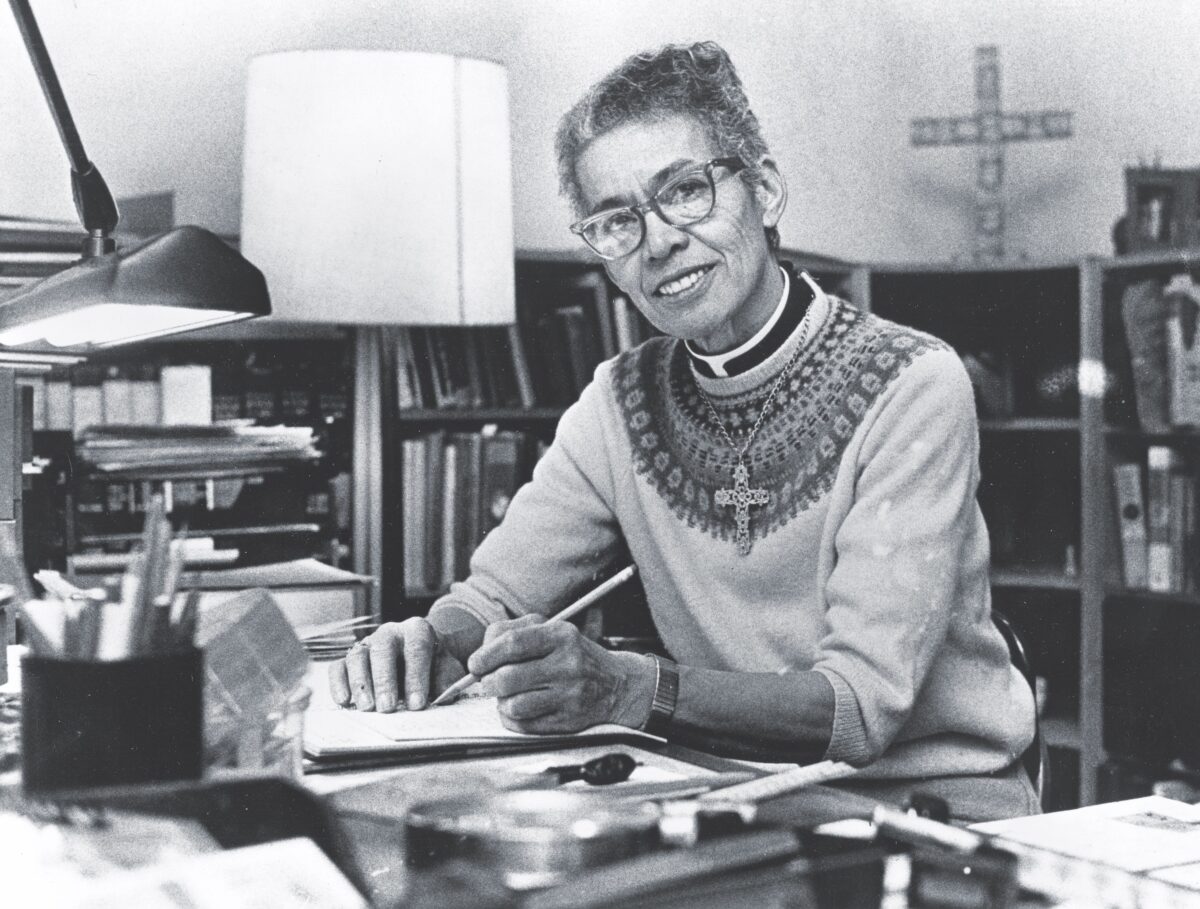

Pauli Murray remained active in civil rights and feminist causes, a one-woman Venn diagram connecting divergent groups, increasingly including interfaith efforts. In 1968, Murray joined the faculty of Brandeis University in Boston, teaching there until 1973. In 1977, after Irene Barlow’s death, Pauli Murray became the first African American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest. That role drew her back to North Carolina, where she served until she died of cancer in 1985. Song in a Weary Throat, an autobiography focusing on her adult life, came out posthumously in 1987. In 2012, the Episcopal Church named her a saint, meaning that her life should serve as ongoing inspiration. In 2017, Pauli Murray’s Durham family home was designated a National Historic Landmark.

(“My Name is Pauli Murray,” a 90-minute documentary on Murray’s life, is streaming now on Amazon Prime.)