President Richard Nixon’s daily briefing on Dec. 20, 1971, reported a buildup of North Vietnamese troops above the Demilitarized Zone and southbound troop movements on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The North Vietnamese air force was moving units south, including the newly established 927th Fighter Regiment, equipped with MiG-21PFM fighter jets. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Adm. Thomas Moorer had advised Nixon in November that Hanoi’s air defense units were attacking AC-130 Spectre gunships and B-52 Stratofortess bombers supporting Laotian Maj. Gen. Vang Pao’s forces fighting communist Pathet Lao insurgents.

Realizing that Hanoi intended to start an offensive in 1972, Nixon ordered the armed services to reinforce their air power in Indochina. That same day Moorer approved airstrikes against military targets up to the 20th parallel, essentially all targets south of Hanoi and the key port at Haiphong. Nixon and the Joint Chiefs thought the bombing would deter Hanoi from launching an offensive the size of the massive Tet Offensive in 1968. They were wrong.

Communist Party First Secretary Le Duan—Hanoi’s actual leader since December 1963, even though Ho Chi Minh was technically the head of government until his death in September 1969—viewed 1972 as an opportune time for a large-scale offensive to conquer South Vietnam. Le Duan believed that America’s anti-war movement would constrain Nixon’s response. Then, if the offensive succeeded as expected, Republican Nixon would be defeated in the November election or at least weakened in negotiations for a peace agreement. Le Duan’s memoirs speak of his preference for Democrats Hubert Humphrey, the 1968 presidential nominee, and George McGovern, who advocated for unconditional withdrawal and became the party’s presidential candidate in 1972.

Additionally, Nixon’s not-so-secret communications with Beijing to establish better relations with China, one of North Vietnam’s major patrons, threatened a source of crucial support for Le Duan, which reinforced his need to damage Nixon politically.

Having imprisoned most Communist Party members who favored a peace agreement, Le Duan faced little opposition to a new offensive. He calculated that Hanoi had the political will to continue fighting while America did not. In June 1971 he set in motion the Spring-Summer 1972 offensive, also called the Easter Offensive. The North Vietnamese Army’s plans were completed by October.

Le Duan ordered his negotiators to take a hard line in talks with their American counterparts. That ploy had worked with President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, but Nixon was a different leader. Diplomatically, Nixon promised the Soviet Union’s Leonid Brezhnev detente and China’s Mao Zedong U.S. recognition if they pressured Hanoi into earnest negotiations. He visited Beijing on Feb. 21-28 1972, and canceled the peace talks on March 23 due to a lack of progress. Hanoi’s intelligence agents learned China was considering an aid cutoff to North Vietnam in exchange for diplomatic relations with the U.S.

Militarily, Nixon increased Hanoi’s costs and losses. He had expanded the bombing on Dec. 25, 1971, allowing strikes up to the 20th parallel. Nixon also liberalized the rules of engagement with strikes on North Vietnam’s airfields and surface-to-air missile sites that threatened U.S. bomber routes. The days of retaliation only for MiG and SAM attacks on U.S. forces were over. Although the targets remained limited, the operations and tactics were not.

The bombing was just one component of Nixon’s plan to end the increasingly unpopular war. He believed a carrot and stick approach might draw Hanoi to a peace agreement. The bombing campaign represented the stick. For the carrot, Nixon promised a total withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam, provided Hanoi returned all prisoners of war and agreed to an internationally supervised cease-fire throughout Indochina.

Previously, the U.S. had refused to withdraw all its forces unless Hanoi did the same. Nixon and Kissinger thought they were offering a good deal and hoped Hanoi would see it the same way. Le Duan did not. He believed South Vietnam was about to fall, rendering Nixon’s “carrot” irrelevant.

Le Duan launched the Easter Offensive’s first phase on March 30, 1972, sending three divisions and supporting units across the DMZ and the Laotian border on their way to Quang Tri. Two days later, April 1 in Washington and April 2 in Vietnam, the Joint Chiefs authorized airstrikes above the 20th parallel, the same day Hanoi launched a corps-level drive toward Saigon.

On April 4, the president told national security adviser Henry Kissinger, “The bastards have never been bombed [like] they’re going to be bombed this time,” as recorded on the Nixon tapes.

Nixon intensified strikes on North Vietnam’s supply lines and logistics facilities and accelerated the air power buildup in East Asia. The U.S. also increased air support to ground forces in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.

On April 9-12, B-52Ds struck the oil facility and rail yard at Vinh, a city between the DMZ and Hanoi. The bombers countered enemy radar with electronic jamming equipment and the largest corridor of chaff (tiny strips of tin foil dropped from the planes to confuse radar) since World War II. Surprised crews in the North Vietnamese air defense system were overwhelmed. The oil facility was destroyed without U.S. losses.

Two days later, American aircraft struck oil and rail facilities around Hanoi and Haiphong for the first time since 1968, using B-52s followed by 100 fighter-bombers. The fires burned for two days. Similar raids destroyed weapons storage areas and oil facilities around Haiphong at the cost of two American planes downed by anti-aircraft artillery.

Yet Le Duan remained unimpressed. The Easter Offensive continued. Hanoi’s drive on Kontum in the Central Highlands halted on April 23, but that was due more to NVA hesitation than ARVN resistance. On April 30, the Joint Chiefs reported to Nixon that all aircraft were in place to conduct a comprehensive bombing campaign against North Vietnam.

Hanoi’s Easter Offensive neared its peak as Kissinger met his North Vietnamese negotiating counterpart, Le Duc Tho, in Paris on May 2. South Vietnamese forces had abandoned their northernmost provincial capital, Quang Tri, the day before. Confident that victory was near, the North’s delegation proved intransigent and, according to Kissinger’s memoirs, insulting. Nixon ordered the Joint Chiefs to present him with options.

On May 4, Moorer offered a plan to mine Haiphong Harbor. Nixon approved it immediately. The next day he got a briefing on the plan for a bombing campaign initially titled Rolling Thunder Alpha. Nixon also approved it immediately.

The bombing campaign, renamed Operation Linebacker, was significantly different from Rolling Thunder (March 2, 1965-Oct. 31, 1968). Notably, in Rolling Thunder the targets were selected by Johnson and other administration officials based on recommendations from the Air Force and Navy and selected to limit civilian casualties. In contrast, the planning for Linebacker was conducted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the execution was carried out by the commanders involved.

For dramatic effect, Nixon announced the bombing at 9 p.m. on May 8 to coincide with the launch of the airstrikes at 9 a.m., May 9, in Vietnam. While the president spoke slowly about the war on national television, the Linebacker campaign opened with the Operation Pocket Money. Aircraft from carrier USS Coral Sea laid a combination of 36 magnetic and acoustic mines (detonated by the metal or sound of overhead ships) in Haiphong Harbor’s two main shipping channels. Three destroyers shelled the anti-aircraft artillery positions southwest of Haiphong.

When Nixon was assured the planes had cleared North Vietnamese airspace, he announced to his TV audience that mining was underway and all accesses to North Vietnam’s major ports would be mined. The president added that he directed U.S. forces to cut off North Vietnamese rail and communications networks to the maximum possible extent. He stated that the air and naval strikes against North Vietnam would continue.

Meanwhile, the seemingly unstoppable North Vietnamese Army continued to overrun the ARVN soldiers protecting South Vietnamese towns. The NVA was attacking with artillery that had a much longer range than the guns of the ARVN defenders. Meanwhile, heavy rains and low overcast severely inhibited air-support operations. Gen. Creighton Abrams, commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, strongly objected to any efforts to divert B-52s away from their support missions for the ground war in the South.

B-52 radar-directed bombing was Abrams’ most effective all-weather close-air-support weapon. The bombers’ accuracy had improved over the years, enabling the planes to drop their loads within 650 yards of friendly troops and strike fear in the NVA. In a change of policy, the Strategic Air Command no longer required B-52 crews to file international flight plans 72 hours before the sortie, taking away the advanced strike warnings that the NVA once received. Nixon accepted his commanders’ recommendation and reluctantly removed B-52s from Linebacker missions to concentrate on bombing NVA forces in South Vietnam.

The Joint Chiefs and Strategic Air Command planners built Linebacker as a systematic air campaign to dismantle North Vietnam’s transportation network and capacity to support military operations. It was designed to isolate the network’s central hubs in Hanoi and Haiphong by attacking both cities’ defenses, tearing up rail networks and destroying all military facilities and supplies in those areas. In that regard, Linebacker shared many features of the Rolling Thunder goals. However, four elements had changed since Rolling Thunder’s conception in late 1964: advances in technology, the increased strength of North Vietnam’s air defenses, the expanded size of its military infrastructure and the determination of America’s political leadership to hit the North hard.

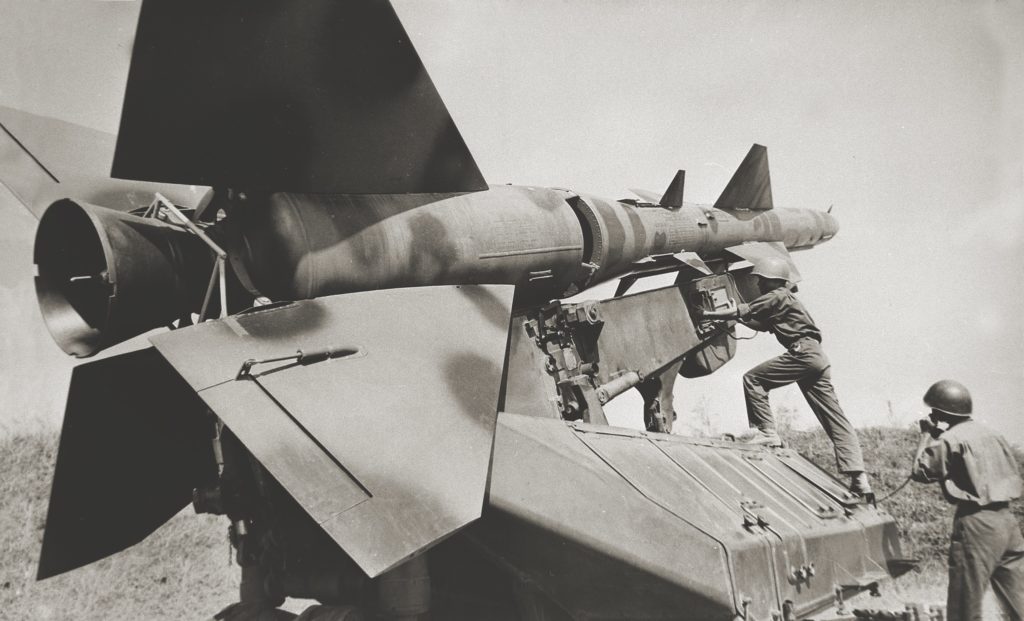

No component of Hanoi’s air defense system was excluded from attack. Airfields, command centers, radars, SAM sites and SAM storage facilities were struck. Radars and communications equipment were jammed. Chaff corridors were created to blind the defenders. The American arsenal included jet fighters, on flights code-named “Wild Weasel,” equipped with sophisticated missiles that could detect, home in on and destroy the radar at SAM sites.

During the Johnson administration, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara emphasized large numbers of bombing runs, not the striking power of those sorties. Large numbers of flights with small strikes required less preparation, takeoff and recovery times, but gave the North Vietnamese a predictable series of piecemeal raids conducted in sequence. Linebacker’s mass raids with powerful ways to suppress air-defense systems were an entirely different problem for Hanoi.

North Vietnam’s official history admits the defenders were not prepared for the size of the strikes or the electronic warfare that supported them. North Vietnamese fighter pilots suffered accordingly. With better air control support, shorter transit-to-target times, the new “loose deuce” fighter formation (two fighters flying together to cover each other) and improved air combat training, U.S. Navy pilots achieved a 6:1 kill ratio.

One Navy F-4 Phantom II fighter-bomber team, Lt. Randall Cunningham and radar intercept officer Lt. j.g. Willie P. Driscoll, downed three MiG-17s on May 10 to become America’s first aces of the war. The Air Force quickly improved the intelligence and warning support for its pilots. By July, it caught up with the Navy, adding three aces of its own: pilot Capt. Richard S. “Steve”Ritchie and weapons control officers Charles B. Bellevue and Jeffrey S. Feinstein, both captains.

After reviewing the first day’s results on May 9, the 7th Air Force commander, Gen. John W. Vogt, decided that all Air Force strikes in the Hanoi-Haiphong area would employ precision-guided munitions, “smart bombs.” With only six precision-guided systems available in Indochina, Vogt’s decision limited Air Force strikes in that area to one a day, but accuracy and effectiveness markedly improved.

Vogt recognized that the new technologies required special training and experience. He initiated the specialization of air wings. The 433rd and 435th Tactical Fighter Squadrons became his primary precision-guided strike units. The 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron assumed the electronic warfare and chaff corridor mission. The 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing focused on air-to-air missions, and the 338th Tactical Fighter Wing hunted SAMs because it had F-105G Thunderchief Wild Weasels and EB-66 Destroyer electronic warfare planes. The specialization paid immediate dividends as crew proficiency and tactics improved almost instantly.

The chaff-laying flights, although they required fighter escorts and jamming support, all but negated Hanoi’s SAM threat. SAM sites resorted to launching 30-50 missiles into aerial “engagement boxes” where they expected the U.S. strike aircraft were flying. That wasn’t effective. North Vietnamese successes were limited to attacks on aircraft flying outside chaff protection.

Anti-aircraft artillery remained a threat, but the increasing availability of precision-guided bombs not only improved strike accuracy but also extended the safe distance from which an attack could be made.

Hanoi lost 17 key bridges in Linebacker’s first three weeks. The destruction of rail yards, petroleum tanks and weapons storage facilities quickly followed. Worse from Hanoi’s perspective, replacement supplies were not assured. Chinese and Soviet deliveries dropped by more than 50 percent.

Interestingly, neither China nor the Soviet Union protested the mining of Haiphong Harbor, the entry point for 90 percent of Hanoi’s war supplies. The bulk of the other supplies were transported on two single-track rail lines that ran from the Sino-Vietnam border and intersected at a rail junction 20 miles north of Hanoi. The railroad connected to the city via the 1.5-mile-long Paul Doumer Bridge, or Long Bien Bridge, over the Red River. That bridge was destroyed two weeks into Operation Linebacker.

The air campaign was complemented by the Navy’s shelling of coastal facilities, radar and anti-aircraft artillery sites, and offshore shipping. On Aug. 27, the 7th Fleet flagship cruiser USS Newport News, the guided missile cruiser USS Providence and two destroyers shelled Haiphong’s coastal defense positions. Four North Vietnamese torpedo boats responded, only to be sunk without inflicting any damage.

Concurrently, U.S. and South Vietnamese aircraft hit Hanoi’s supply convoys on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and inside South Vietnam. In transitioning from guerrilla war tactics to traditional combined arms operations for the Easter Offensive, the NVA had acquired the logistical tail that American air power had been organized and trained to strike.

By late July, NVA artillery units had to ration daily ammunition allotments because the commanders could rely only on previously stocked supply caches.

American intercepts of radio communications indicated supply deliveries were down by 70 percent. NVA casualties mounted. Allied air support devastated units in combat. Some units reported losses exceeding 50 percent of their personnel and equipment.

The Easter Offensive had begun to sputter by late July. Kontum never fell.

ARVN forces advanced on Quang Tri to retake the city. Le Duc Tho agreed to resume private talks on Aug. 4.

Early discussions went poorly with both sides exchanging recriminations. Progress remained elusive. The anti-war movement was gaining momentum, and the presidential election was only 10 weeks away. A frustrated Nixon dropped one of his key conditions—the complete withdrawal of NVA forces from South Vietnam. North Vietnamese negotiators remained intransigent. Nixon ordered the Air Force and Navy to increase strikes around Hanoi and Haiphong.

The August monsoon brought heavy rains that inundated most Air Force bases in Thailand and South Vietnam. Conditions over North Vietnam negated the use of precision guidance systems. The 7th Air Force went to two missions a day and returned to dropping “dumb bombs” while reducing the number of jamming, refueling and SAM suppression flights in support of the missions. Chaff flights also had to be reduced. While the weather inhibited North Vietnamese MiG operations as much as it did American flights, the diminished chaff and jamming support resuscitated Hanoi’s SAM force.

The Air Force countered with “hunter-killer” teams of F-105G Wild Weasels and F-4s carrying cluster bombs. Sensors on the F-105, the “hunter,” identified the location of SAM radars, and the pilot fired anti-radiation missiles, or ARMs, that forced the shutdown of SAM radars. Then the F-4, the “killer,” destroyed most of the site with a cluster bomb.

By late September, however, intelligence reporting indicated that Hanoi had repaired most of its transportation network and fuel storage facilities. Electricity generation and most major highways had also been restored. North Vietnam had exploited the reduced bombing period to rebuild and reconstitute its capacity.

On Oct. 8, Hanoi dropped most of its preconditions for a peace agreement. Le Duc Tho no longer required the U.S. to remove the South Vietnamese leadership and replace it with a coalition government that included the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong). He also accepted the U.S. proposal for an internationally monitored cease-fire.

Le Duc Tho and Kissinger offered a tentative agreement on Oct. 23. Nixon ordered cessation of Linebacker that same day. U.S. combat losses totaled 104 aircraft: 55 downed by anti-aircraft guns, 26 by MiGs, 18 by SAMs and five by actions taken to evade MiG intercepts.

Le Duan faced severe criticism for his handling of the war, even with the Communist Party’s “peace faction” imprisoned. The army’s heavy losses had eroded his support.

Linebacker had depressed public morale. Le Duan needed to buy time to identify and suppress the new opposition and, most of all, reduce the casualties and damage. Mao had told him the Americans would leave soon. The Oct. 23 agreement contained that requirement. Once the Americans were gone, Le Duan would reconsider his options.

Linebacker I, as it came to be known, marked the world’s first widespread deployment of precision-guided weapons, high-tech electronic warfare and air defense suppression (the Wild Weasels). However, even though American air power had driven Le Duan to seek a peace agreement, Linebacker I had not proved as effective as initially assessed. It inflicted more damage on North Vietnam’s warfighting capacity in four months than Rolling Thunder had in 3½ years, but Hanoi retained a significant combat capacity.

Intelligence indicated that the NVA had stockpiled more than six months of food, fuel and ammunition in caches across Cambodia and in its South Vietnam enclaves before launching the Easter Offensive. With its railroads and ports largely shut down, North Vietnam moved supplies by trucks and ferries.

In August, truck convoys started importing 10,000 tons of supplies monthly from China. Air defense command and control networks became more robust, dispersed and redundant. Supply shortages did not stop the Easter Offensive. The offensive ended because air power inflicted heavy NVA troop casualties and equipment losses among front-line units in the South.

Vogt, the 7th Air Force commander, studied those reports and lessons learned from the campaign. The studies proved to be valuable after South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu’s refusal to sign the October agreement forced negotiations into a new and more difficult round. Nixon assuaged Thieu’s concerns by promising overwhelming U.S. air support if Hanoi violated the cease-fire agreement, but then Le Duan refused to sign the agreement.

Before long, B-52s were back over the skies of North Vietnam in what became known as Linebacker II, or the Christmas Bombing Campaign. Linebacker I had set the stage and opened the door for a negotiated peace. Linebacker II would seal the deal.

Carl O. Schuster is a retired Navy captain with 25 years of service. He finished his career as an intelligence officer. Schuster, who lives in Honolulu, is a teacher in Hawaii Pacific University’s Diplomacy and Military Science program.

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.