The young army commander quickly surveyed the enemy battle lines. Thus far his opponent, a much older general officer, had fought well. But as the youthful leader studied the enemy left, he concluded that his seasoned adversary had made a serious mistake. The opposing troops on that flank occupied a long ridge just a short distance away, across a beautiful orchard-speckled valley. It should have been a good position, but its left was vulnerable—“in the air,” as they used to say. He planned to hit that flank hard.

It was time for decisive action. With a flurry of hand movements, he ordered his men forward—across that vale, against that opposing ridgeline. As his units closed with the enemy, he heard the volley fire—a distinctive ripping sound—and saw the defending artillery’s bright muzzle flashes. He even thought he could smell the acrid smoke of black powder.

The battle would soon be over. With a couple of rolls of a die, cross-indexed with the odds on the combat results table, the young commander eliminated several enemy pieces, removing them from the map. At that point his opponent conceded, saying something about how he had failed not only his army but also President Abraham Lincoln. It was a tremendous victory—one he would always remember. He had won the Civil War’s most famous engagement, and he’d defeated his father, all thanks to his wonderful birthday present: the Gettysburg battle game created by Charles Roberts.

Charles Swann Roberts, “the father of board war-gaming,” was born in Baltimore on February 3, 1930, and grew up just outside the city in Catonsville. Two fascinations dominated his childhood. One was the military. He once recalled how he and his young friends created a war game that involved maneuvering pins and needles—the game’s units—across a fictional battlefield.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Railroading was his other obsession. Both his father and grandfather were veteran Baltimore & Ohio Railroad men, and a great-great-uncle, his namesake, had been the president of that line from 1848 to 1853. Naturally, Charlie caught “railroad fever,” but his father persuaded him to look elsewhere for a career. After graduating from Catonsville High School in 1947, Roberts worked for his local newspaper, the Herald-Argus, and as a copyboy for the Baltimore Sun.

In 1948, when he turned 18, Roberts enlisted in the U.S. Army. On his discharge in 1952, Roberts was commissioned in a Maryland National Guard infantry regiment and, as he would later write, “applied for what was known as a Competitive Tour of Duty [in Korea], at the successful completion of which my reserve commission would be magically converted to a Regular one.” As he waited to hear about his application, Roberts took a stab at advertising, working at VanSant Dugsdale & Company, Baltimore’s largest ad agency, and at Emery Advertising Corporation, just north of the city in Hunt Valley.

Roberts was convinced, however, that his future was with the military. He hoped to serve in combat, and he wanted to learn everything he could about war—its theories, doctrines, and tenets. “The Principles of War [are] to a soldier what the Bible is to a clergyman,” he would later write. “The Bible, however, may be readily perused….Wars are somewhat harder to come by.”

In 1952 Roberts decided that while he was training with the National Guard, he would learn the nuances of war in a way that was “less noisy”—through a board game. No such game existed at the time, however, so he designed his own, one with which he could command armies and army groups, not just small platoons. It was the right move at the right time. In 1952, with the Korean War stalemated, the U.S. Army had mothballed its competitive tours program. Roberts briefly considered U.S. Army Ranger School but feared its two weeks of jungle training. Then the U.S. Air Force turned him down because he failed its hearing test. Roberts’s career in the military had hit a dead end.

The dream, however, lived on in Roberts’s Catonsville apartment. The result, in 1954, was Tactics, which today is widely considered the first commercial board game about war. “I found game design interesting, and I knew a thing or two about marketing,” Roberts would later tell an interviewer. “I didn’t start out to build a board game business. Fate just led me to that point.”

Roberts named his new enterprise Avalon Game Company, after a historic neighborhood near his home. Over the next four years, doing business exclusively by mail order, Roberts sold about 2,000 copies of Tactics—a number, he later recalled, that “either netted or lost thirty dollars.” After getting home from his full-time day job in advertising, he would spend his evenings packaging and addressing his orders for shipment. The future multimillion-dollar war game industry was thus born as a part-time venture—“almost as a lark,” Roberts would later write.

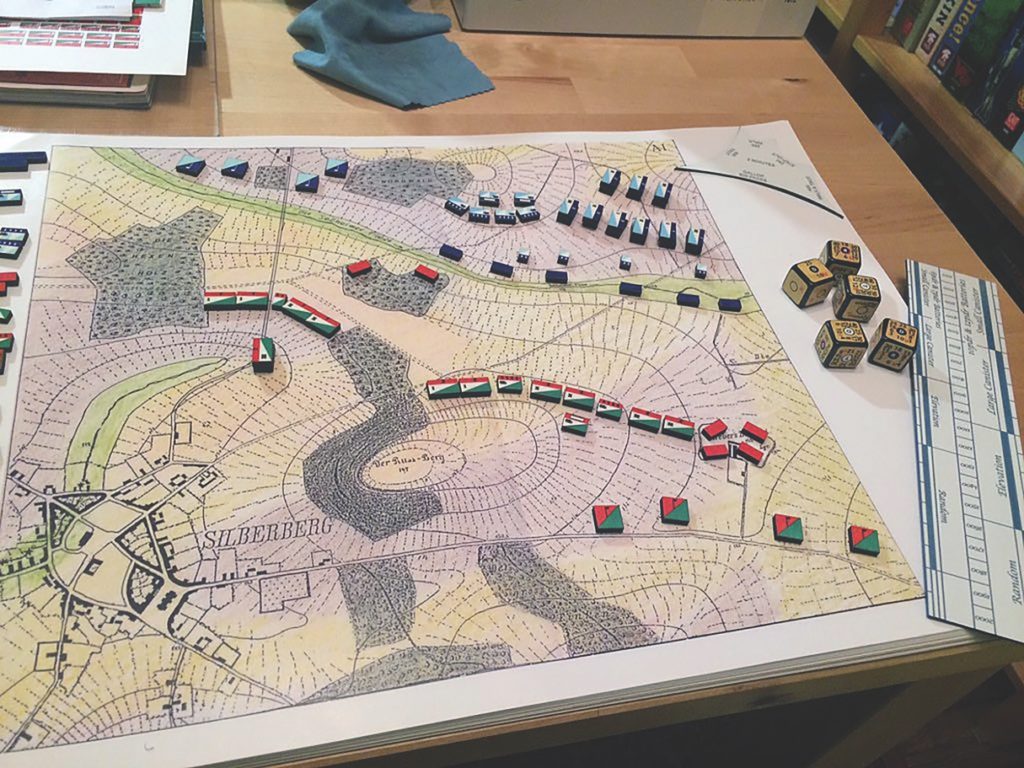

Tactics came in a 14-by-22-inch black-and-red box. The cover copy, written by the young ad man, read, in part: “Tactics. The new, realistic land army war game! Designed and perfected by an infantry officer.…Actual principles of war apply….An excellent gift for the ‘Chess and Checkers’ type.” The game’s map, mounted on sturdy cardboard, unfolded to 22 by 28 inches, a nonstandard size that bewildered printers. On the game board, overprinted with a square grid, two hypothetical modern nations—“Blue” and “Red”—battled it out with army units portrayed by cardboard “counters,” the war-gaming term commonly used for playing pieces. These pieces represented regular infantry units, armored units, headquarters units, and specialized forces such as mountaineers, paratroops, and amphibious units.

Modern-day war gamers would recognize some of the game’s basic mechanics. Every combat unit had a movement factor and a combat factor. Movement across the grid was from square to square. Players resolved the game’s combat by using an odds-ratio combat results table. A unit with 4 combat factors attacking a unit with 2 combat factors, for example, would have a 2-to-1 attack ratio. Once players determined the odds for an attack, they rolled a six-sided die, and the result was cross-indexed on the table. Outcomes included retreats, advances, and such dire battlefield results as “defender eliminated” and “attacker eliminated.”

Tactics paved the way for an entirely new pastime, but the game’s map was still rather primitive. The mountains looked odd, and coastlines and rivers followed the grid’s square edges, making them look extremely unnatural. The rivers also had another problem: They ran “in the wrong direction,” as Roberts later admitted.

Tactics, of course, wasn’t the first war game. Chess—whose beginnings are unclear—is obviously a battle simulation, albeit an abstract one. Its earliest known predecessor appeared around the seventh century in India and traveled from there to Persia, the Muslim world, and eventually to southern Europe, where its current form was established in the 1600s.

Chess variants more akin to today’s war games started to appear in Europe in the late 18th century. One example was designed in 1780 by Johann Christian Ludwig Hellwig, a Prussian mathematics professor, who published an updated edition in 1803. Called Versuch eines aufs Schachspiel gebaueten taktischen Spiels von zwey und mehreren Personen zu spielen (or “Attempt to build upon chess a tactical game which two or more persons might play”), it featured a map that measured 49 by 33 squares (compared to chess’s 8 by 8). Across the map’s varying terrain—squares that contained mountains, swamps, or watercourses—the players maneuvered infantry, cavalry, and artillery units, each of which had unique movement capabilities.

The similarities to chess made Hellwig’s variant attractive to chess players, but the map’s square grid made it unrealistic. Only one unit could occupy a square at a time, despite the area of that square, and—in a problem that later plagued Tactics—all the natural features were rigidly fitted to the rectilinear grid. That artificiality was especially noticeable in rivers that ran perfectly straight or turned at

90-degree angles.

This early war game interested the public, but not the military—until Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reisswitz, a skilled fencer, violinist, and, most importantly, a first lieutenant in the Prussian Guard Artillery Brigade

created one of his own.

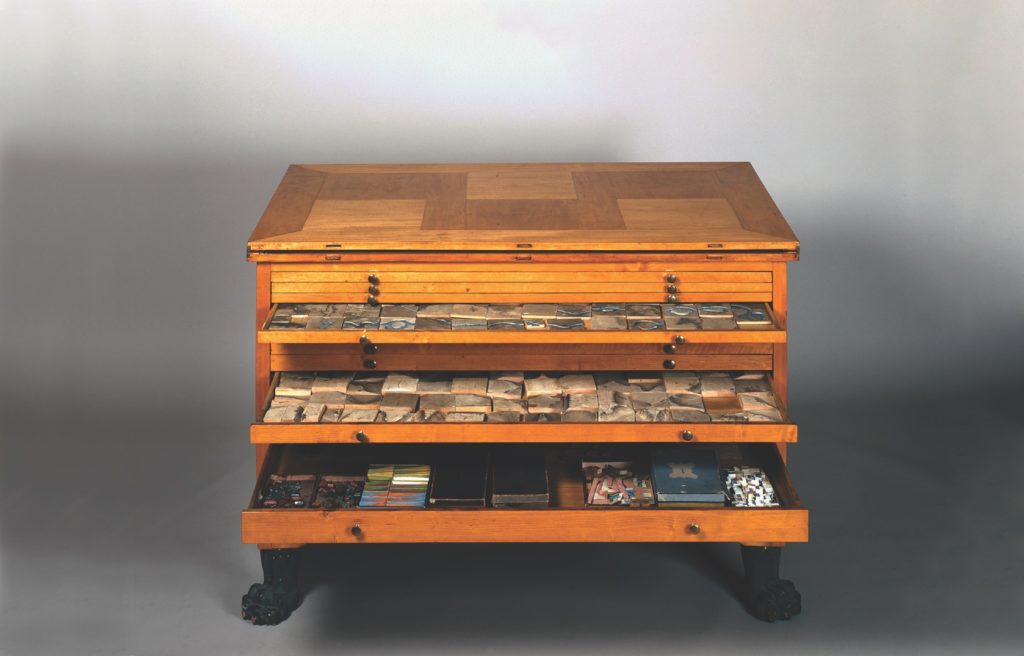

In 1824 Reisswitz presented the Prussian general staff with a highly realistic war-themed board game he’d created with his father. Designed as a military training tool, his Kriegsspiel (meaning literally “war game”) was played across a gridless, accurately illustrated terrain map with rectangular metal pieces that represented the various infantry regiments, cavalry squadrons, and artillery batteries. Prussian units were painted blue, enemy units red (an arbitrary choice that nonetheless established a military mapping convention wherein “friendlies” always appear in blue and “enemies” in red).

Without a grid to limit them, Reisswitz’s units could move freely on the board, subject to the varying natural features, of course, and tables in the rule book stating how far the foot soldiers, or horsemen, or cannons, could move in a turn. Based on information gathered during the Napoleonic Wars, these tables even accounted for whether a unit was marching, running, or—in the case of cavalry—galloping.

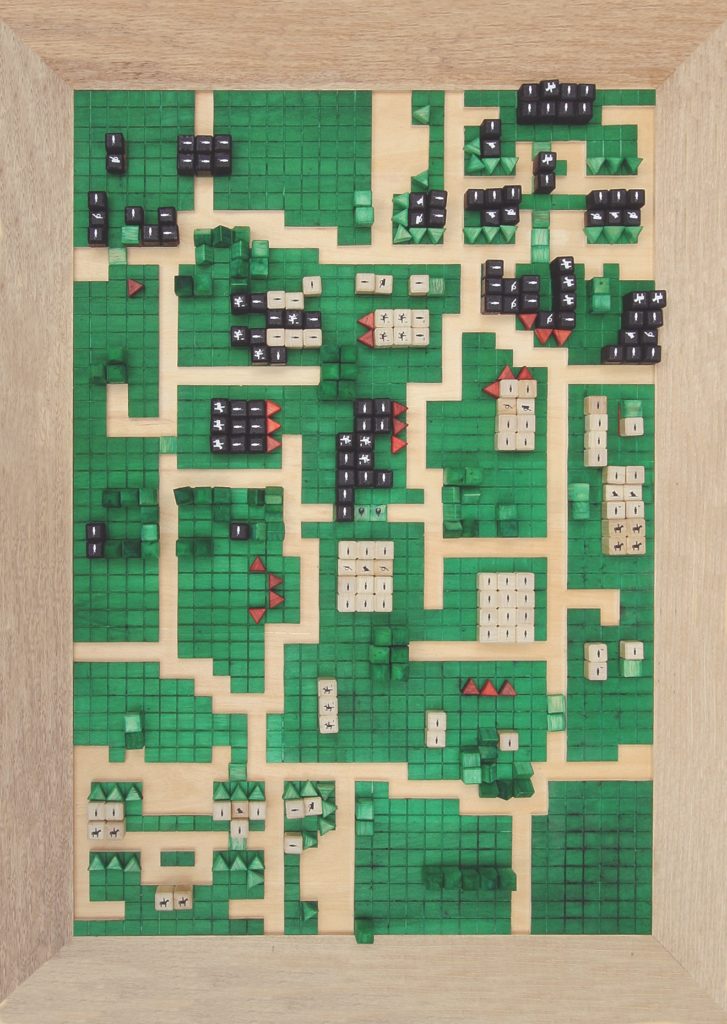

A reconstruction of Reisswitz’s 1824 Kriegsspiel. (Matthew Kirschenbaum, CC BY-SA 4.0)

And Reisswitz’s war game was chock-full of other realistic touches: options for movements that are not visible to the enemy; rules that covered morale and unit exhaustion; playing pieces whose sizes were based on actual unit frontages; and combat resolution using dice (thus adding randomness to the simulation). Additionally, the Kriegsspiel units, unlike chess pieces, could suffer partial losses before being removed from play.

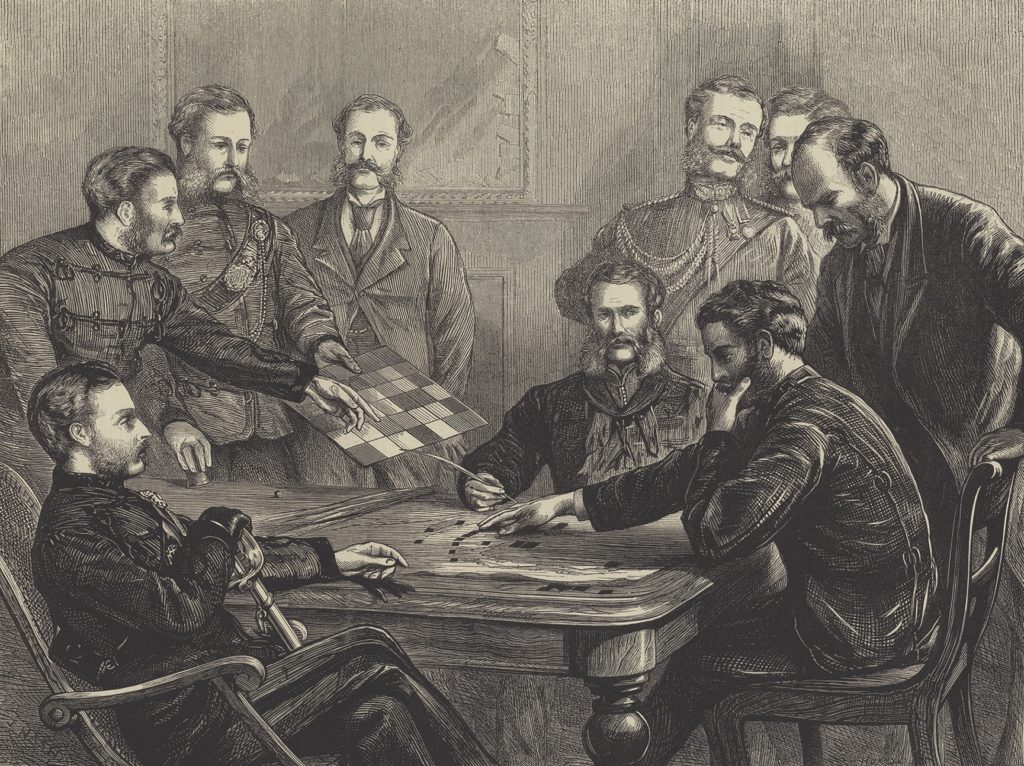

An umpire administered this battle simulation. After receiving written orders from the opposing players, the umpire moved the metal battalions according to ruled measurements, rolled the dice, determined the resultant casualties, and executed the combat results. The use of an umpire kept Kriegsspiel focused on training and decision-making instead of competition.

The Prussian generals were greatly impressed. “It’s not a game at all!” wrote General Karl Freiherr von Müffling, a military theorist, chief of the general staff, and Waterloo veteran. “It’s training for war. I shall recommend it enthusiastically to the whole army.” Reisswitz’s Kriegsspiel thus became the first board war game to be used for military training. It attracted very little attention outside Prussia until 1871, when the Prussian military soundly defeated French forces in the Franco-Prussian War. Prussia’s relatively easy victory was attributed by many to its reliance on war game training for its officer corps.

Soon, civilian war game clubs were established across Europe—Oxford University’s Kriegspiel [sic] Club was founded in 1873—and other militaries started taking a serious look at battle games. The U.S. Naval War College, for example, made war-gaming an official part of its training in 1894.

In 1958, four years after launching Tactics, Roberts determined to publish more games. “I [had] learned something about the marketing of games in this [first] reconnaissance-in-force,” he would later write, “and…decided to have a go on a larger and more serious scale.” But when he applied for a new business license, he found that another firm was using his original company’s name. Thinking of the ridge on which his house was situated, he added a word and rechristened his business The Avalon Hill Game Company.

Roberts’s 1950s home sat on a ridge in the Avalon neighborhood in Catonsville, Maryland, outside Baltimore. (GreenC, cc by-sa 4.0)

Now Roberts went at it full-time. Continuing to operate out of his home, he hired a staff and put out three games of his own design in 1958: Tactics II, Gettysburg, and the railroad game Dispatcher.

Tactics II was a direct descendant of the 1954 title. The map was the same, as were the playing pieces, except that the new version featured circular headquarters units. The new, expanded rules challenged players. The rule booklet noted that while the mental problems posed by the game were not easy, “it is in the correct solutions to these problems…that the Avalon Hill player finds the ultimate in self-satisfaction.” The booklet also included a basic treatise on modern combat—unity of command, economy of force, the use of surprise, and so forth—and presented the different types of attacks: frontal, flanking, and envelopment. (Tactics II was so popular that it would be republished in 1961 and again in 1973.)

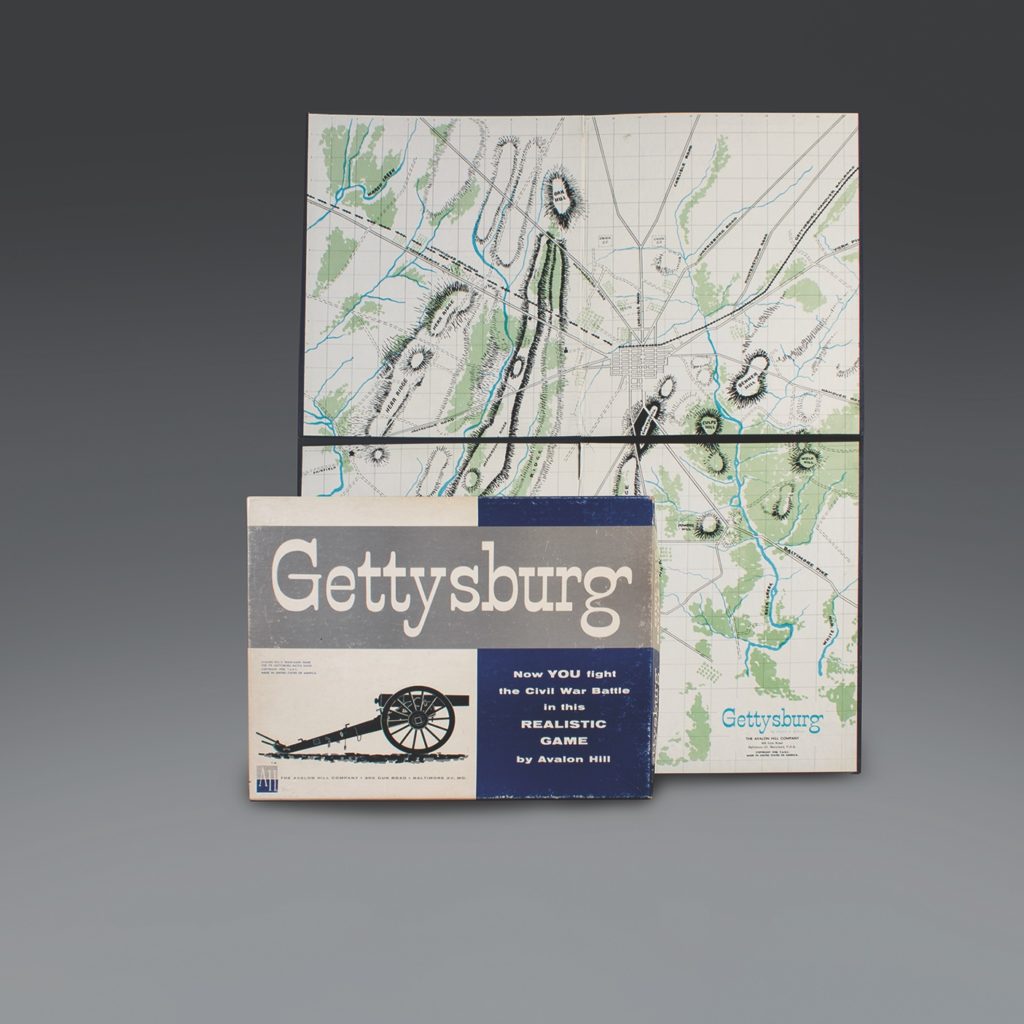

The Gettysburg title marked an important milestone in the history of board war-gaming. It was the first game in the genre based on an actual battle. Roberts chose the Battle of Gettysburg with the upcoming American Civil War Centennial in mind. Played on a map of the battlefield overprinted with a black grid of fairly large squares, Gettysburg unfolded much like existing games played with painted miniature soldiers. Surprisingly, the grid was used only for tracking hidden movement, not to regulate the normal movement of the game’s uniquely rectangular playing pieces. For normal movement, the players instead employed carboard “range cards.” The length of the range card was a counter’s maximum movement; the width was the greatest distance it could fire.

The Gettysburg combat results table was similar to that used in Tactics II, but attacking and defending were quite different. Gettysburg’s combat counters, representing infantry divisions, cavalry brigades, and artillery battalions, had an actual facing, or orientation; meaning that they had a front, two flanks, and a rear. An attacker could greatly increase the odds in his favor by assaulting the flanks and the rear.

Avalon Hill counted Gettysburg a success; it sold well. But, as Roberts later recalled, because the game was released without being play-tested, the rules were vague and incomplete, so players were often on their own when it came to resolving some of the game’s conundrums.

Designing war games in the early years, Roberts admitted, was difficult. New wargame players with the “chess-and-checkers mindset,” as he put it, were used to moving only one playing piece at a time. Now, however, his battle games were introducing a wholly new method of play: Players could move any or all of their pieces, and each piece wasn’t required to move its maximum movement allowance. Additionally, unlike chess and checkers, the results of an attack weren’t automatic; they were resolved with the roll of a die. Another difficulty was finding the historical data—orders of battle, unit sizes, times of arrival on the battlefield, and so on—essential for accurate design. Roberts wanted to ensure that his players were not just enjoying the combat simulation but also learning about the events his games portrayed.

By 1959 Avalon Hill was doing so well that Roberts moved the operation into a commercial site in Baltimore. That year U-Boat became the company’s first naval war game, the first copies of which featured metal miniatures—submarines and destroyers—instead of die-cut cardboard playing pieces. In the basic game for novice players, one U-boat and one destroyer attempted to sink one another while maneuvering across a square-gridded map. At a disadvantage, the Allied player was uncertain of the enemy sub’s position and depth. The advanced game pitted three U-boats against three destroyers. (The 1961 revision of U-Boat featured better rules covering torpedoes and depth charges. This improvement established what became a standard operating procedure at Avalon Hill: the continual revising and updating of well-selling games as the customer base grew and as those customers gained experience and demanded better and more accurate games.)

In 1959 the company also published Verdict, its first game designed by outsiders—in this case, corporate attorneys. Roberts was beginning to sense that his battle games could carry the company forward, but he wanted to hedge his bets by branching out.(Verdict was reprinted in 1961.)

The following year the business moved again, this time to downtown Baltimore. Roberts knew he needed to acquire new creative talent to expand Avalon Hill, so he lured Thomas N. Shaw, a high school friend, away from a local

ad agency. In 1959 Shaw had successfully created and self-marketed two sports games: Baseball Strategy and Football Strategy. The company produced but one game in 1960, Management, a business strategy title designed by Roberts.

In 1961 Avalon Hill moved yet again, this time to an industrial park in Baltimore, and doubled the size of its product line by publishing seven new games. An important innovation first appeared in its 1961 lineup of war-themed board games: the use of a hexagonal grid. On a square grid, equidistant movement is available in only four directions: up, down, right, and left. Diagonal moves, to the contrary, are not equidistant: They allow a playing piece to move farther. On a hexagonal grid, however, movement to any of the six adjacent hexagons (or “hexes,” as gamers call them) is always equidistant. This simple and elegant change became very popular and has been a key aspect of war-themed board games ever since.

The company’s 1961 releases, all designed by Roberts, were Chancellorsville, D-Day, and Civil War. Chancellorsville, a recreation of Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s greatest victory, featured a heavy game board, over 300 die-cut counters, and a pamphlet on the May 1863 battle. But Chancellorsville didn’t sell well—perhaps because the map board was a pastel-colored graphics disaster—and was discontinued two years later.

D-Day simulated World War II’s Western Front between June and September of 1944, (not just, as the name implies, the June 6 Normandy landings, which are normally executed on the game’s first turn). Today it’s judged one of Avalon Hill’s “classic” war games—all of which employed relatively simple move-attack game mechanics. Several unique aspects made D-Day memorable: The Allied player could choose to invade France at several other possible locations, including the southern coast. And the German player had flexibility in the placement of his forces, but of course he’d have no knowledge of his enemy’s intentions.

Rounding out the 1961 historical lineup was Civil War, a very abstract strategic-level board game using plastic pawns instead of die-cut cardboard counters. The game was printed only once, evidently in low numbers, and was quickly discontinued. Its scarcity has made it a valuable find for collectors.

In 1961 the Baltimore Sun described Avalon Hill as “one of the leading game publishers in the nation.” Sales that year totaled nearly $1 million. What made the company’s games so popular? It was their basic design, Roberts told reporter Carroll E. Williams, along with the fact that—unlike other games that used dice—Avalon Hill’s battle games relied heavily on the participants’ intellect. They were “games of almost pure skill,” he said.

And the company’s distribution network had grown. Avalon Hill’s games were being sold in leading department, toy, and bookstores all across the country. The nation’s largest mail-order houses, too, were advertising Avalon Hill games.

With his business and marketing background, Roberts managed the business well, and it grew rapidly. The war games were the best sellers, but the company continued to publish what it called “civilian titles.” In 1961 these included Nieuchess by Roberts, “an abstract attempt to bridge the gap between chess and wargames,” a complete failure; Verdict II, created by Tom Shaw, another failure that was soon dropped from the product line; Air Empire, another Shaw creation—an “application of the Management game system to the transportation theme”—that netted lackluster sales; and LeMans, the company’s first sports game, designed by Rodney Mudge and Scott Wright, who had first manufactured it on their own in 1956. It was a good game but a slow seller. “Industry historians are always surprised,” Roberts noted, “when I point out that Avalon Hillpublished more civilian titles than wargames during its first five years.”

That trend held true in 1962, when three of the company’s five new products were non-military. The first two were Tom Shaw creations, Baseball Strategy and Football Strategy, which he’d originally sold in mailing tubes. Avalon Hill bought the rights, boxed them up, and had a ready-made sports line. In JZ, “the TV ad man’s game,” up to six players competed for advertising accounts. Created by WJZ-TV in Baltimore as a promotional item, it’s considered one of the Holy Grails of Avalon Hill collecting.

The historical simulations released in 1962 were Waterloo, designed by Lindsley Schutz and Tom Shaw, and

Bismarck, a team effort by Roberts, Schutz, and Shaw. Waterloo, like Normandy, had a misleading title. Instead of focusing tactically just on the battle, the game—with its map portraying a large section of south-central Belgium—was actually strategic. It simulated Napoleon’s entire Waterloo Campaign.

The Avalon Hill product line had grown substantially, but sales were plummeting. Writing 20 years later, Roberts cited many reasons: the rise of discount retailers, “runaway” television advertising that smothered small businesses, and a “nasty recession” in 1960–1961 that plunged the company into the red. Additionally, he wrote, “too many low-selling civilian titles made our line imbalanced.” Enormous amounts of time and corporate resources had been spent chasing one of Roberts’s elusive dreams. This potential product—a tactical war game he called Game/Train—was first created as a 20-foot-long training aid for the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Nonetheless, by the fall of 1962 Roberts believed that they’d turned the company around, though it was highly leveraged financially. Its new products in 1963 included a Schutz-and-Shaw creation, Stalingrad—another of the company’s classics that never sold well—and Word Power by Tom Shaw. Unfortunately, 1963 also witnessed the release of a line of Shaw-designed games for preschoolers—Imagination; What Time Is It?; Doll House; and Trucks, Trains, Boats & Planes—that were all huge flops.

By the end of 1963, Roberts would later write, “we were in effect working for our creditors.” He planned to file for bankruptcy on December 13, but the company was saved from extinction at the eleventh hour by two of its creditors: Monarch Office Services, which printed Avalon Hill’s game components, and J. E. Smith & Company, which manufactured and printed the boxes and assembled the games. Roberts had high praise for A. Eric Dott, Monarch’s president: Of all the creditors, only Dott had bothered to visit Avalon Hill’s offices.

Avalon Hill was now completely reorganized—expenses were cut to the bone, and the company moved yet again, to another Baltimore location. Only one employee was retained: Tom Shaw, who now became Avalon Hill’s marketing director. His new duties included making sure that the company’s battle games were historically accurate and, with the help of a panel of over 100 play testers, ironing out any bugs before the games were manufactured.Roberts declined a position in the reorganized company.

In 1964 Avalon Hill settled into a schedule of publishing two new games a year. One of that year’s releases was a Roberts creation, developed with help from Schutz and Shaw. Played across a map depicting the North African coastline, Afrika Korps simulated the back-and-forth World War II contest that pitted German field marshal Erwin Rommel (“The Desert Fox”) against British general Bernard Law Montgomery.

Afrika Korps represented Roberts’s last association with the company he had founded and built from scratch.

Under Dott’s leadership Avalon Hill, in the manner of a huge battleship, began turning itself around. Its big successes included Blitzkrieg (1965), Panzerblitz (1970), Richthofen’s War (1973), and Squad Leader (1977).

The rise of computer games in the 1980s, however, spelled doom for publishers of war-themed board games. In 1998 Dott sold the company to industry giant Hasbro for $6 million. Avalon Hill is now a brand of Wizards of

the Coast, a Hasbro subsidiary. Its 14-title product line includes Axis & Allies, Diplomacy—both conflict simulations—and Scooby-Doo: Betrayal at Mystery Mansion.

After his departure from the war games industry in 1964, Roberts spent a few years as a corporate executive and then became the head of a Baltimore publishing house that specialized in titles for the Catholic market. In 1973 he and his second wife, Joan Barnard Lynch, founded Barnard, Roberts & Company Inc., which published Catholic titles, even though Roberts was not Catholic or even particularly religious. Eventually, however, the company shifted its focus to railroad history. Roberts became a railroad historian, editing, writing, or coauthoring 30 books before he died in 2010.

It’s been almost 60 years since Charles Roberts published his last war game, Afrika Korps, but the industry still reveres him. In 1974 a group of enthusiasts established the Charles S. Roberts Awards to honor excellence in war-gaming. They had to twist Roberts’s arm to go along with the idea because, as he had always said, he’d never intended to found a company, an avocation, or an industry. “I would rather be known for something I had set out to do,” he said. “This just happened.”

this article first appeared in military history quarterly

Facebook: @MHQmag | Twitter: @MHQMagazine