In March 2021, a 21-year-old man killed eight people, six of them Asian, at three Atlanta area massage parlors. Cops attributed the rampage to the White perp’s hatred of his own sex addiction, but local Asian Americans saw more: “xenophobia” aimed at them, as Georgia state Representative Bee Nguyen put it. The slaughter was the most savage of a year-long spate of incidents in which Asian Americans going about their lives were insulted, harassed, or beaten, often to the tune of rants about Covid: “You are infected,” “You are the virus,” et cetera ad nauseam. “We’ve gone from being invisible to being seen as subhuman,” wrote U.S. Representative Grace Meng (D-New York).

This story began over 150 years ago.

Until 1848 there were no Asians to speak of in the future- or then-United States. The Pacific was 7,000 miles wide, and imperial Chinese edicts forbade emigration. The Gold Rush changed that. Word of a “Mountain of Gold” in California spread to the British outpost of Hong Kong, and by 1851, 25,000 Chinese had defied distance and the law to take a whack at the mountain.

These immigrants took up trades besides mining. Some 10,000 Chinese laborers helped build and blast the Central Pacific Railroad, the first transcontinental line’s western leg, over and through the Sierra Nevada range. Charles Crocker, the magnate who employed them, noted approvingly that his crews’ ancestors had built the Great Wall of China. As California turned to agriculture, Chinese labored on farms. In cities and towns, they ran laundries and restaurants. By 1870, there were 63,000 Chinese in the United States, almost all in the West.

Typical Chinese immigrants’ jobs and enterprises paid meagerly, but required little or no investment, and offered greater return than farming stones in Taishan, the impoverished district adjacent to Hong Kong from which most migrants came. Initially, America’s Chinese were overwhelmingly male. Chinese fraternal organizations steered them to jobs and collected dues as a payback. Émigrés sent whatever surplus remained home to their families; many intended to return to China. Typical of sojourning immigrants, they kept to themselves, as much as possible holding to the old ways.

Chinese were a new race in the American mix, and their long queues, mandated by the ruling Manchu dynasty, made them doubly conspicuous. But so long as times were flush, they were welcome enough.

In his western travelogue Roughing It, Mark Twain called the Chinese “quiet, peaceable, tractable, free from drunkenness, and…as industrious as the day is long. A disorderly Chinaman is rare, and a lazy one does not exist.” Bret Harte’s ominously titled poem “The Heathen Chinee” in fact describes White card sharps being outsmarted by an Asian mark. After the Panic of 1873 brought bad times, however, the goodwill vanished and the gloves came off.

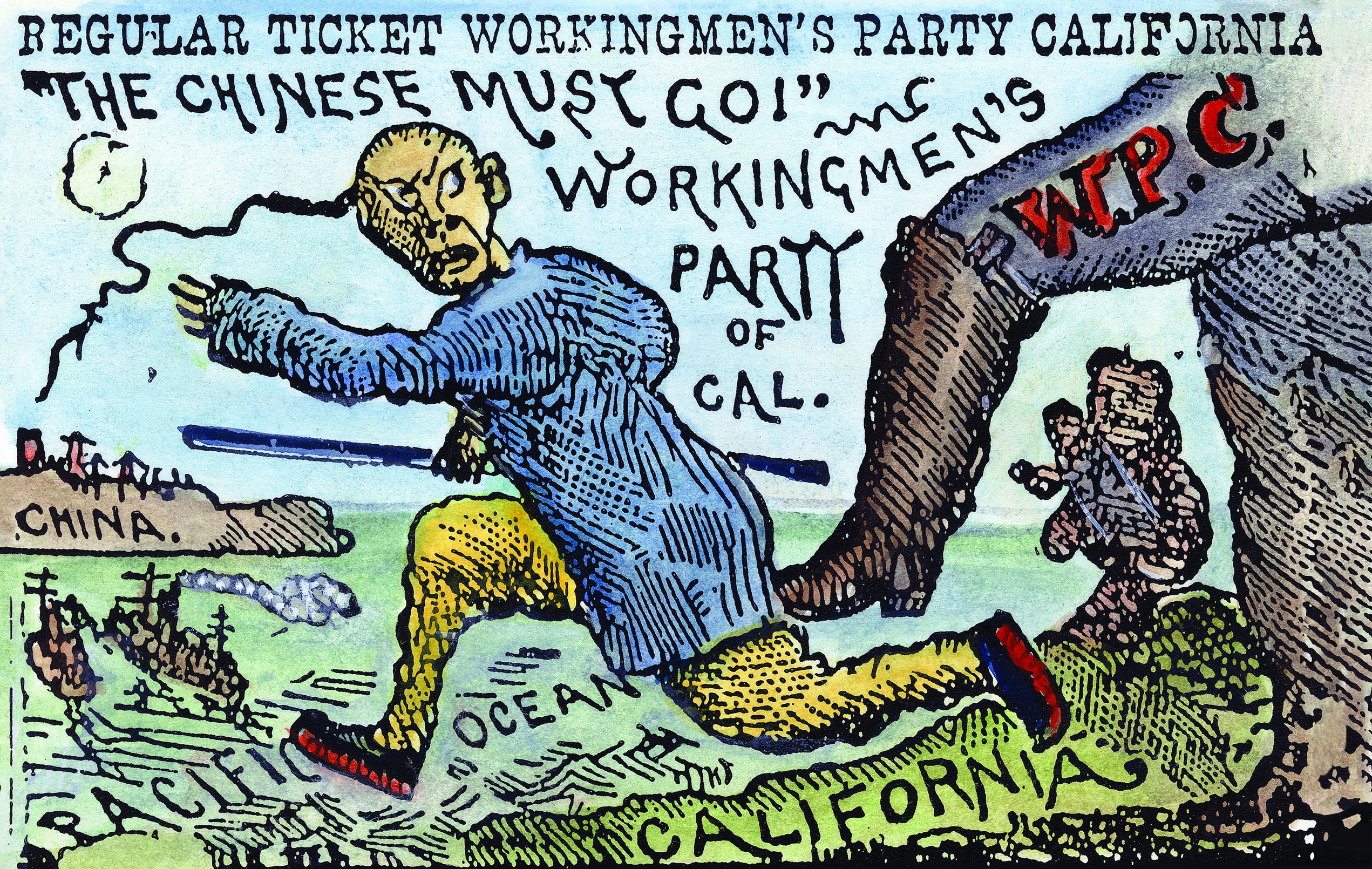

By doing scut work for low wages, the Chinese, it was alleged, were depressing the American labor market. This was not always so: The Central Pacific paid White and Chinese workers the same $35 a month—though Chinese required no company-provided meals because they cooked for themselves. The prime anti-Chinese demagogue on the West Coast was Denis Kearney, a San Francisco drayman who was himself an immigrant from Ireland. A fellow radical described him as “a man of strict temperance in all except speech.” In rabble-rousing stemwinders delivered at the Sand Lots, a vacant parcel next to City Hall, Kearney excoriated wealthy Whites, but always signed off with “The Chinese must go.” Kearney’s vehicle, the Workingmen’s Party of California, managed by 1878 to win a quarter of the seats in the state senate and hold a fifth of the state assembly.

Congress took note of burgeoning anti-Chinese sentiment. In 1880 the United States signed a treaty with China allowing Washington to limit inflow of Chinese laborers in a “reasonable” manner. In 1881, Congress showed what it saw as “reasonable” by approving a bill, sponsored by Senator John Miller (R-California), slamming the doors for 20 years. President Chester Arthur vetoed the measure early in 1882, saying that two decades was an unreasonably long time and “a breach of our national faith.” Congress countered with a ten-year hiatus. Arthur accepted. The one-decade ban was renewed in 1892 and in 1902 made permanent. An unanticipated effect of excluding Chinese was to create demand for Japanese laborers, triggering demands to exclude them, too. Unlike China, Japan was a modernized militant nation that would take a formal rebuke amiss. So President Theodore Roosevelt brokered a tacit deal, “the gentlemen’s agreement,” whereby America agreed not to stop Japanese from coming here provided Japan agreed to prevent them from leaving there. It took a world war to relax the Chinese ban—a bit. In 1943, as a gesture to our ally Chiang Kai-shek, Washington allowed Chinese to trickle in at a rate of 105 persons per year.

The Hart-Cellar Act of 1965 ended national immigration quotas. The gates opened wide. Chinese came in families, not just as lonely men, and from the entire Middle Kingdom, not just Taishan. A gauge of the new diversity: bland Cantonese restaurants serving made-in-America dishes like chop suey were joined by eateries offering fiery dishes from Sichuan and elsewhere in China. The 2018 census estimated there to be over five million Chinese Americans. (The count of Asian Americans, meaning everyone with roots from Pakistan to the Philippines, topped 20 million.) The days when Chinese laborers competed for low-wage jobs are long gone; for years Chinese Americans have been known for the traits Twain enumerated, making them a “model minority”—i.e., one that causes no trouble. The reputation adheres to Americans from near (Korea) and not-so near countries (India). This is what Rep. Meng had in mind when she said that Asian Americans hitherto have been “invisible.”

Two recent developments have brought Asian Americans into focus. One is Covid, obtusely nicknamed by Donald Trump the “kung flu.” The evidence is powerful that the Chinese government systematically concealed what it knew about the origin and spread of the coronavirus from its own people and to the world. That is on the heads of Xi Jinping and cronies, not the heads of Chinese people there or anywhere else. It is nevertheless no surprise that the ignorant, the demented, and the criminal take the pandemic out on random Asian passersby—more so when the pandemic itself is overstressing police departments.

Meanwhile, the idea of unfair Asian competition has been revived, not in regard to sweat labor, but to high-end educational slots. Asian American students are overrepresented in elite institutions, from the California state university system to New York City’s specialized public high schools (Stuyvesant High School, the jewel in Gotham’s crown, is 74 percent Asian). Efforts to modify conditions, by boosting enrollment of underrepresented minorities, get pushback from Asian American voters and parents. California Asians broke heavily against Proposition 16, a 2020 ballot measure to allow reinstatement of affirmative action in state university admissions. Meanwhile, on the opposite coast, a group called Students for Fair Admissions has been suing Harvard since 2014, alleging the existence of tacit quotas that cap Asian admissions. The plaintiffs have asked the Supreme Court to rule on their case.

When people are oppressed by inner demons or by competition, fair or unfair, they look for scapegoats—and the most convenient are people who do not look like themselves.

This story appears in the August 2021 issue of American History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.