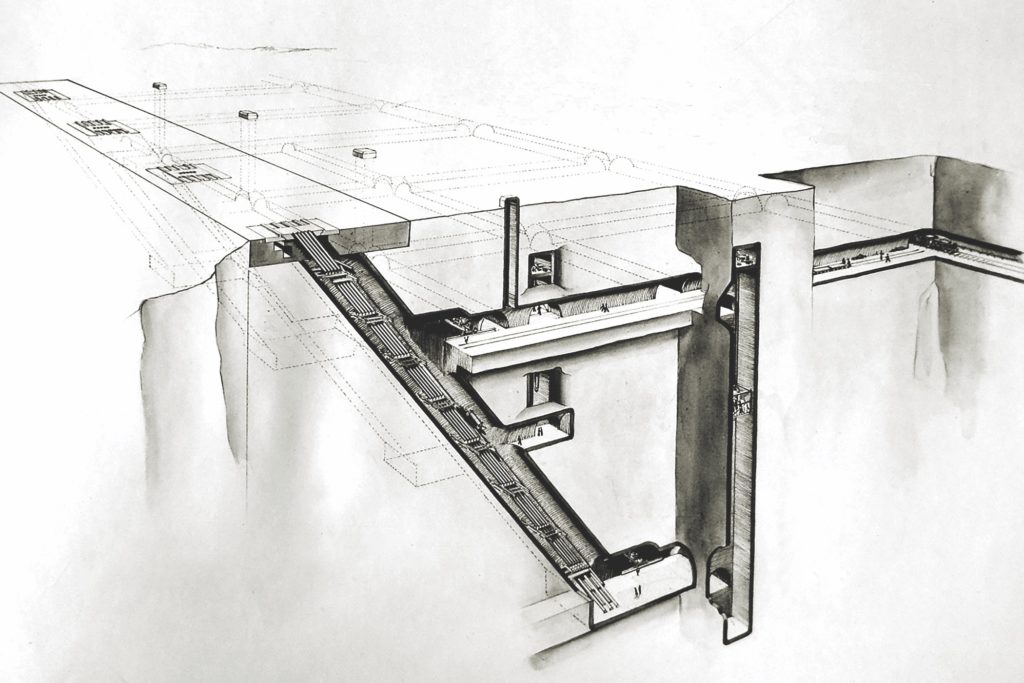

Germany built a vast subterranean complex in Mimoyecques, France, to house their secret weapon.

Students of World War II are familiar with Nazi Germany’s V1 and V2 weapons that brought terror to southern England in the last year of the war. Less known is the V3—which the Nazis also called the “London Cannon”—a massive, multi-charge gun designed to shoot a 215-pound shell nearly 100 miles. Adolf Hitler hoped it would blast the British capital to smithereens.

A ballistics engineer named August Coenders sold the concept of a super cannon to the Führer in 1942. Coenders’s design called for an initial charge in the gun’s breechblock that would propel a 150mm shell into a huge, 139-yard-long barrel. The shell would then be accelerated through the barrel by successive detonations of 32 additional charges, creating a muzzle velocity of 1,640 yards per second. According to Coenders’s calculations, a deployment of 50 guns launching 3,000 rounds a day would saturate London with shells over a 15-square-mile area.

But the practicalities of designing such a weapon and keeping it secret from the enemy would soon cause Coenders no end of problems. Those problems have been preserved for posterity in the Mimoyecques (pronounced “me-mo-e’-eck”) museum in northern France, 12 miles southwest of Calais, the nearest port to England across the English Channel. It’s deep in the countryside and not a particularly accessible site, but then that’s why the Germans chose this place to install its V3 cannon.

Hitler entrusted the V3 project to Armaments Minister Albert Speer. Speer’s first task was to select a suitable location in which to construct the necessary cavernous bunkers. Of paramount importance for any potential gun site was its proximity to London, but the Germans chose Mimoyecques in June 1943 for several additional reasons. Six miles from the coast, it was too far inland to be targeted by Royal Navy guns or a commando raid. It was also close to a railway line, along which munitions, materials, and workers could be transported. Finally, the geological structure of Mimoyecques was ideal—the hill of solid chalk reached a depth of 110 yards, ensuring stability for the weapon’s foundations.

It’s easy to miss the Mimoyecques museum from the roadside. Were it not for half a dozen flags fluttering on their poles, I might have driven past the site. Walking the short distance from the car park to the reception center, I pass a concrete slab set in the ground, which, I learn later, was built to a thickness of 16 feet to protect the muzzles of five guns beneath.

Inside the reception center, one staff member raises an eyebrow at my attire and advises me that shorts and a T-shirt might not be adequate 100 feet below ground at a temperature of 50 degrees. I pull a sweater from my backpack that I’d packed at the last moment, and boy was I glad.

Workers, numbering between 1,200 and 1,500 in total, began arriving in June 1943. Some were skilled engineers from Schachtbau und Tiefbohr, a German company that specialized in underground construction, but the backbreaking excavation work was done by the Reich’s Organisation Todt, which undertook a vast array of engineering projects in Germany and its conquered nations. At Mimoyecques, Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, and Poles were bused in from their spartan camps a few miles west to slave for 12 hours at a time.

Their job was to build two identical bunkers, 3,000 feet apart. In all, the intention was to have 10 inclined weapons chambers, 138 yards long, dug into the earth at an angle of 50 degrees, with each chamber housing five guns—50 in total. The Germans also built two railway tunnels 100 feet underground and 650 yards long in order to bring supplies and ordnance for the planned garrison of 1,200 men. This material would be stored in a large network of galleries carved off the railway tunnels.

I exit the reception center and descend down a concrete walkway, leaving behind me the light and warmth of the surface. I feel both nervous and excited as I listen to the echo of my footsteps. The network of tunnels is well-lit but nonetheless I shiver, and not just because of the temperature. In the human psyche the subterranean has sepulchral connotations, and this sense is reinforced in Mimoyecques: the museum, open to the public from April to October, closes for six months in fall and winter and becomes one of the biggest bat sanctuaries in France. If bats give you the creeps, don’t worry; they make themselves scarce during the summer months.

It was not bats but the British who made life disagreeable for the engineers and laborers. In September 1943, as construction was ongoing, Allied reconnaissance photographs detected abnormal activity at Mimoyecques. In November the Royal Air Force bombed the site, and although the damage was minimal, the Germans now knew the British were onto them.

All this is explained in 15 billboards in English located throughout the 650 yards of chambers. A brief video playing on one of the walls shows a virtual reconstruction of how the Germans expected the cannon to wreak havoc on London. Then there are the relics: the rotting husk of an excavator once used for tunneling and a small wagon that carried the chalk rubble to the surface.

As the workers toiled underground, Coenders continued to test his design, but the results weren’t good. The barrel was constructed in numerous sections, each one about 10 feet in length, but trials found that this produced a brittleness that didn’t allow sufficient muzzle velocity for the shells to reach London, about 93 miles northwest. In November 1943 Speer reduced the planned number of V3 guns from 50 to 25, and in April 1944 cut the number again to three batteries of five guns each.

Of course, the British knew none of this; they were aware only that something big was being constructed at a site near the Channel coast with openings on the surface facing London. When the first V1 rockets—the “doodlebugs” that my father still remembers watching flying overhead toward London as a six-year-old—began hitting southern England in mid-June, the Allies intensified their bombing campaign against Mimoyecques.

In total, between November 1943 and August 1944, British and American aircraft dropped 4,102 tons of bombs on Mimoyecques. The nearby village of Landrethun-le-Nord was flattened and had to be rebuilt after the war, but because of the depth of the chambers and the 157,000 cubic yards of concrete that had been cast inside, only 11 workers were killed in the raids.

There is a memorial to these workers inside one of the side chambers, as there is to the most famous Allied airman killed while raiding Mimoyecques, U.S. Navy lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Kennedy and copilot Lieutenant Wilford J. Willy were flying a converted B-24 Liberator packed with explosives toward the site as part of Operation Aphrodite. This ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful initiative envisaged destroying important Nazi targets such as V-weapon sites and U-boat pens by converting B-24s into precision-guided missiles. The aircraft would be piloted into the air by a skeleton crew, who would bale out once airborne, leaving the flying bomb to be directed to the target by radio control from an accompanying “mother” plane. Kennedy and Willy took off on August 12, 1944, but as the aircraft climbed over eastern England, it exploded. The memorial deservedly honors the courage of Kennedy, but unfortunately Willy’s name is omitted.

Though the technology for what today are called drones was still dangerously primitive, another military innovation had already derailed Mimoyecques’ V3 program prior to Kennedy’s ill-fated mission. On July 6, 16 RAF Lancasters each released a 12,000-pound “Tallboy” bomb over the V3 site from a height of 25,000 feet. Packed with 5,500 pounds of powerful explosives, these 21-foot-long steel bombs hit Mimoyecques at supersonic speed, generating shock waves below ground similar to a small earthquake. Several of the gallery arches collapsed as the bombs struck, bringing down tons of rubble that blocked the gun chambers.

While the Germans abandoned the site in August 1944, there was one last big explosion to rock Mimoyecques when, on May 14, 1945, the British Army destroyed the two bunkers with 36 tons of TNT to ensure the site could never be used to bring terror to Britain. As Winston Churchill said in a speech that same week, the discovery of “multiple long range artillery which was being prepared against London…might well have seen London as shattered as Berlin.”

One end of the tunnel system was partially reopened in the 1980s, and it’s here that the museum has been situated since 2010. There are half a dozen guided tours annually to parts of the site that are normally out-of-bounds, including the surface area turned into a lunar landscape by the devastating Allied bombing.

It takes me an hour and a half to tour the tunnels and read all the billboards.

I emerge blinking into the bright, warm sunlight. It had been an informative visit, but I’m glad to be back on the surface—and, as a Londoner, I’m relieved that Hitler never saw his V3 in action. ✯

WHEN YOU GO

The Mimoyecques complex, on the outskirts of the village of Landrethun-le- Nord, is seven miles from the rail station of Calais- Fréthun, which is serviced by regular high-speed trains from Paris (approximately two hours) as well as three daily Eurostar trains from London. Renting a car at Calais-Fréthun will allow you to explore the region fully, though there is also a taxi stand at the station; a round trip to the complex is approximately $50.

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

The nearest decent hotel is the Hôtel de la Baie de Wissant, six miles west on the Atlantic coast. Wissant was a popular resort in the interwar years, and its golden beach is a reminder of why. Less tranquil is the port city of Calais, which has numerous hotels and restaurants. The museum’s reception center sells a small range of soft drinks and snacks.

WHAT ELSE TO SEE AND DO

Ten miles west of Mimoyecques is the Museum of the Atlantic Wall at Audinghen, housed in one of four casemates that composed a battery of German coastal artillery. La Coupole, a World War II museum inside one of the launching bases of the V2 rocket, is 30 miles southeast of Mimoyecques and also boasts a 3D planetarium. ✯

This article was published in World War II’s October 2020 issue.