The U-boat pens at Lorient, France, are a silent yet striking tribute to every man and woman brave enough to take to sea in a submarine.

I AM BLESSED WITH FINE WEATHER when I visit the Lorient submarine base in Brittany on the northwestern coast of France. The Atlantic Ocean sparkles under the sunshine, and in the marina an armada of yachts, dinghies, trimarans, and catamarans add their own bright colors. Men and women busy themselves repairing sails, painting hulls, and swabbing decks, while on the quayside those feeling less energetic sit eating and drinking.

It could be a scene from any of the myriad ports along the 2,130 miles of French coastline but for several incongruous intruders on Lorient’s Keroman Peninsula: three enormous concrete U-boat bunkers, built by the Germans as a base for submarine attacks on Allied shipping in the North Atlantic. From a distance, their sheer size and the thickness of the concrete make them look like the gap-toothed grins of giants.

The Germans saw the potential of Lorient within days of occupying France in the summer of 1940. Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander-in-chief of the U-boat fleet, arrived in Lorient on June 23 and chose the port as one of his five French bases, along with Brest, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice, and Bordeaux. Of the five, Dönitz prioritized Lorient because it had avoided large-scale sabotage damage by the vanquished French military. Such was the speed of the spring 1940 German advance across France that Admiral François Darlan’s pledge to scuttle the French navy’s fleet and render all ports inoperable was not fulfilled. Consequently, at Lorient, the naval arsenal workshops were functioning; the fact that the adjacent fishing harbor had a rail link north and south was an additional boon.

Dönitz believed—more so than Adolf Hitler or Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the head of the German navy—that U-boats were key to winning the naval war against Britain. Cut off its supply line to North America, reckoned Dönitz, and Britain would be starved into surrender. By the end of June 1940, German workers, arms, and equipment began arriving in Lorient and, on July 7, U-30 became the first submarine to make the base its port of call.

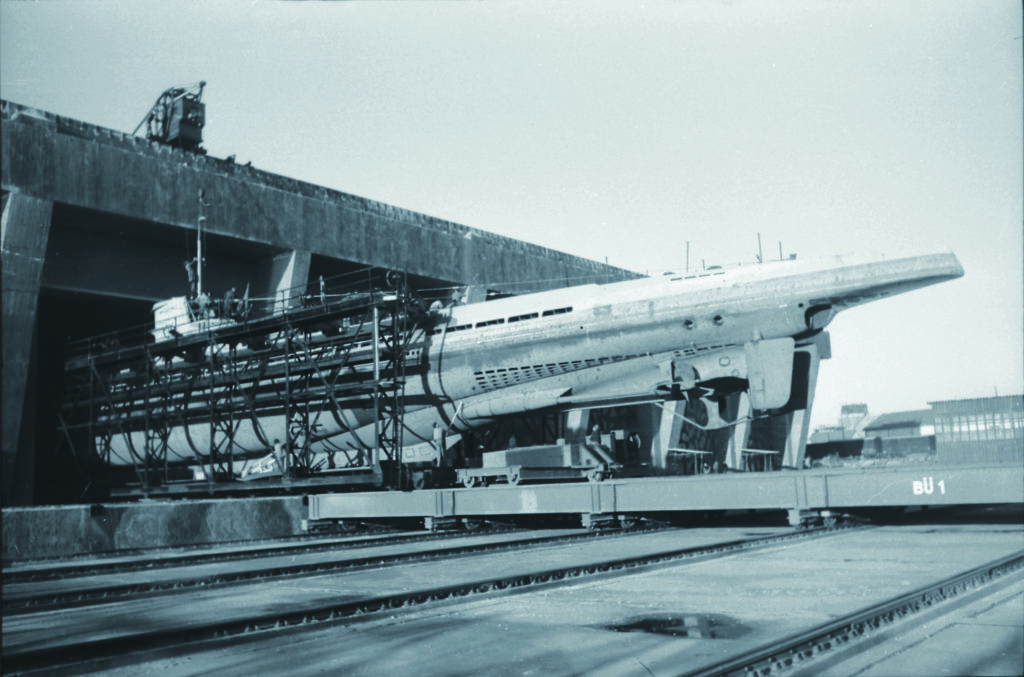

U-30 was initially protected only by a camouflage net; the Germans then erected two large sheds of concrete and wood, one on either side of the slipway ramp in the fishing harbor. But Dönitz quickly realized it was imperative to build concrete bunkers to protect the U-boats against British air raids—the first major Royal Air Force attack came on August 22, 1940—and he decided to erect them above ground to avoid the time-consuming excavation work required for sea pens. To construct the bunkers, the Germans brought in 15,000 civil engineers and laborers from Organization Todt (named after its founder, Fritz Todt) that since 1933 had built many and massive Nazi construction projects and whose ranks were swelled by the forced labor of men from occupied Europe. Meanwhile, armories, workshops, and supply depots sprang up; by the start of 1942, the base was home to more than 5,000 German personnel and 4,300 French staff.

Construction on the first bunker, K1 (“K” stands for “Keroman”), began in February 1941, three months before K2’s foundation stone was laid. Each bunker took seven months to complete, loomed 59 feet high, measured 374 feet in length, and had a 12-foot-thick roof. At 453 feet, K2 was wider than K1 because it had seven pens (to K1’s five), as well as a barracks for 1,000 personnel and a garage. Larger than both was K3, the last of the three bunkers to be built.

Standing in front of K3, I gaze in wonderment at its intimidating size. K3 measures 550 feet in length and 465 feet across, with a floor area of 258,333 square feet. Its concrete roof is 25 feet thick, twice that of the roofs of bunkers K1 and K2. This increase in size was a response to the growing power of Allied bombs. On August 6, 1944, the RAF dropped a 12,000-pound “Tallboy” bomb on K3; the bunker withstood the blast.

To get another view of the three bunkers, I walk half a mile across the mouth of the Ter River along the picturesque coastal path that links the Keroman Peninsula to the Kernevel Peninsula. The route takes me inland for a few hundred yards, skirting a wooded nature reserve, and then curves around and heads back toward the ocean. Couples are sitting on the grassy banks of the river enjoying the sun as I head to the tip of the Kernevel Peninsula. Here stands the elegant Kérillon Villa, constructed in Renaissance style in 1899. It was in this villa that Admiral Dönitz established his staff headquarters in November 1940. (“Ker” is the Breton word for “place.” For centuries Brittany was an independent kingdom, only unifying with France in 1532, and its people remain fiercely proud of their Celtic language and culture.)

The entire complex, called “La Base,” sprawls over 50 acres and encompasses the bunkers, the marina, three restaurants, two museums, and what’s known as “Sailing City,” an indoor ocean venture where visitors learn about Lorient’s proud history of competitive sailing. The development is testament to the ingenuity of the town council, which was devastated when the French Ministry of Defense abandoned Lorient as a military submarine base in 1997. The closure could have had a ruinous effect on the local economy, but 22 years later La Base is a vibrant and diverse hub, drawing tourists, businesses (which have installed offices inside the bunkers), and professional sailing teams.

The international flavor of La Base is evident in the fact that the staff in the museums, stores, and restaurants speak English; the museums’ interactive displays are similarly bilingual. The smaller and older of the two museums tells the stories of submarine wrecks, while the principal museum, housed in K2, explores the history of Lorient through the centuries. There is some fascinating footage from World War II, particularly of U-boats arriving back from patrols. About a third of exhibits are devoted to the wartime era, and if there is a weakness in the museums it’s the lack of a German perspective; it would have been interesting to hear more of what life was like for the occupiers, whether on U-boat patrol or in constructing the bunkers. But again, history is written by the victors.

The museums are a treat, but there is much to be said for simply strolling around La Base at one’s leisure. I find a park bench by the water’s edge and sit for a few minutes in the sunshine, my gaze alternating between the bunkers in the distance and the guidebook I bought in the museum store. I then head to K1, where in front of one of the pens I watch two men repairing a small boat.

The engineers who constructed the U-boat base would be proud to know that their work is still operational, particularly given the ferocity with which the Allies tried to destroy the three bunkers. The RAF’s August 1940 bomb raid was ineffectual, and the British did not subject the base to sustained large-scale bombardment until 1943. By then, not only had the bunkers been constructed, but the Germans had also installed a formidable antiaircraft defense around the city. Still, in the first three months of 1943, British and American bombers dropped thousands of tons of bombs on Lorient, laying waste to the city and port while reducing its civilian population from 46,000 to 500. Most were evacuated, although 206 were killed in air raids. Those that remained sought refuge in the underground city center shelter—which is preserved in its original condition and accessible on an official guided tour—though people would have been just as safe sheltering in the one million cubic yards of reinforced concrete comprising bunkers K1, K2, and K3. The three bunkers passed into new ownership on May 10, 1945, two days after the German commander of the Lorient Pocket signed an unconditional surrender. The French soon established their own submarine fleet in Lorient; one of their Cold War vessels, Flore, is now a museum piece on the esplanade between bunkers K1 and K2. I get a sense, passing through the Flore, of what a remarkable breed submariners are to endure such a life.

Of the 38,000 men who served in U-boats in World War II, only 8,000 survived. No other branch of any service of any nation suffered such a high casualty rate. La Base is a silent yet striking tribute to their sacrifice and that of every man and woman brave enough to take to sea in a submarine. ✯

WHEN YOU GO

Lorient is 300 miles west of Paris and serviced by a regular high-speed train; the trip takes three hours. La Base, three miles from the train station, is accessible by taxi or the T2 bus. The nearest airport is in Brest, 85 miles northwest, and offers direct flights from Paris, London, and other cities.

Where to Stay and Eat

The hotel nearest to La Base is the Best Western Plus Les Rives Du Ter, just one mile away. It overlooks the Ter River and has a bar, restaurant, and pool. The La Base complex contains a crêperie, bistro, and restaurant, providing a comprehensive selection of food and drinks.

WHAT ELSE TO SEE AND DO

The stunning island of Groix lies nine miles off Lorient and is accessible by regular ferry service. With hotels and restaurants, 25 miles of bicycle paths, the only convex beach in Europe, and a 1,900-acre nature reserve—the reserve’s Pointe de Pen Men cliffs are known for its 1836 lighthouse and the colonies of nesting marine birds—the island is perfect for a few days of R&R.

About 30 miles southeast of La Base is the extraordinary Quiberon Peninsula. Nine miles long and just 72 feet wide at its narrowest point, the peninsula offers spectacular walks, the remains of a Roman fish farm, and a Bronze Age fort. Saint-Pierre-Quiberon, the peninsula’s main village, features seafood restaurants, art galleries, and shops.

This story was originally published in the October 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.