As he set out in January 1673 on the arduous journey that would initiate the first regular mail run between the colonial cities of New York and Boston, the trailblazing post rider, whose name has been lost to history, was instructed to “comport [himself] with all sobriety and civility to those that shall entrust you,” to be on the lookout for military deserters and runaway slaves, to assist anyone in distress along the way, and to note for the benefit of those coming after “passages and accommodations at Rivers, Fords, and other necessary places.”

This first mail run, which took just under three weeks to complete, had been inaugurated by the royal governors of New York and Connecticut — Francis Lovelace and John Winthrop — on instructions from England’s King Charles II, who wished his “American subjects to enter into a close correspondency with each other.” Though moderately successful, this monthly postal service was suspended just eight months later.

During the 17th century, American colonists did not view an intercolonial mail system as a pressing need. The sparsely populated settlements along the Atlantic Coast corresponded more with England than with each other, and the few overland trails that existed did not encourage travel between the colonies.

The First Real uS Post

The first real postal system in the English colonies was begun under a royal patent in 1692. The system worked reasonably well, with weekly mail service among several cities from New Castle, Delaware, to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but it was not a profitable venture. Letters carried “outside the mails” provided competition that reduced the system’s revenues. In 1707, the Crown bought back the patent and took control of the colonial postal system, appointing a succession of postmasters general during the next 68 years.

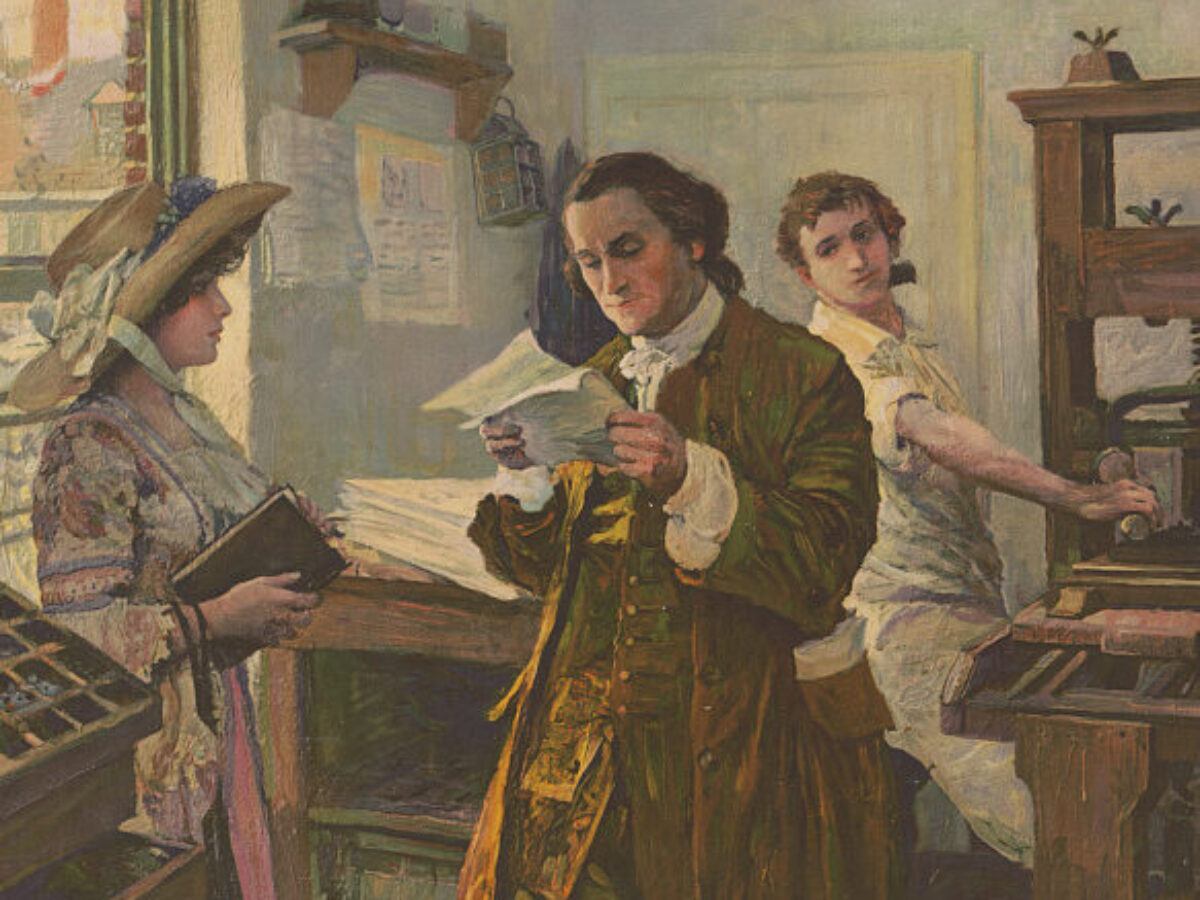

Among those appointees was Benjamin Franklin — printer, newspaper publisher, and beginning in 1737, Philadelphia’s postmaster. Aware that travel at government expense and mailing privileges — perquisites that would allow him to promote his ideas throughout the colonies–came with the office of postmaster general of the colonies, Franklin vigorously pursued the appointment. His efforts were rewarded in 1753 when he and William Hunter of Virginia were named co-deputy postmasters general for the Crown.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

While in office, Franklin developed new post roads, setting out milestones to show how far a postman, who was paid by the mile, had traveled; established faster service to Europe; expanded routes between Canada and New York; and instituted overnight post riders between New York and Philadelphia that allowed for an exchange of letters between those cities in just two days. He also invented the pigeon-hole system for mail distribution and developed an early postal inspection service, “bringing postmasters to account.” In 1761, under Franklin’s watch, the colonial post office showed a profit for the first time. And for the next several years, it returned a surplus to the British treasury, a feat in which Franklin took great pride.

But the colonists were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with Britain’s postal policies. They began to view the high British postal rates as a “grievous” form of taxation without representation and took steps to undermine the Crown’s postal monopoly.

Although he had argued that postal rates differed from the hated Stamp Tax of 1765 because they were payment for a service rendered, Franklin’s open support of the colonists on related issues won him disfavor with the Crown, and he was dismissed from office in 1774. Soon after, William Goddard established an alternative post office, controlled by committees in the various colonies. Goddard’s “Constitutional Post” served the colonists’ needs until July 26, 1775, when the Second Continental Congress took control of the postal system and named the experienced Franklin postmaster general.

Revolutionary mail

During the Revolutionary War, the postal service helped to unite the country in a common cause. Post riders carried the mail at great hazard to themselves between armies in the field and a government that shifted locales in order to avoid capture, as well as between soldiers and their families.

The government created by the Articles of Confederation, which took effect in March 1781, recognized the importance of a good communication system among the states. But rivalries among the now-sovereign states and between the states and the weak central government–coupled with the severe economic problems facing the new confederation–adversely affected its post office department. Thanks to a series of reforms by Ebenezer Hazard, who was appointed postmaster general in 1782, the ailing system managed to remain afloat.

When the Founding Fathers drafted a new constitution in 1787, they included a provision authorizing Congress to “establish post offices and post roads.” Accordingly, Congress passed legislation creating the United States Post Office in 1789. The organization and the scope of its authority, however, were not determined for three more years, and the old Confederation Post Office remained in place in the interim.

The First US Postmaster General

The job of directing this nebulous body fell to Samuel Osgood of Massachusetts, named postmaster general by President George Washington in 1789. Osgood inherited a disorganized and impoverished postal system that consisted of 75 post offices and more than 2,000 miles of post roads. Local post offices often were no more than a portion of a shop or tavern counter, while post roads included vast stretches of swampland or mud-locked and tree-stump-infested barriers.

Finally, in 1792, Congress established a central postal policy, setting postage rates according to the distance that the mail would travel. Part of the Treasury Department, the Post Office was ordered to be self-supporting and to use any profits to extend service. By stipulating that Congress, not the postmaster general, would be responsible for establishing post roads, the law gave the American people a voice in postal affairs through their representatives and senators, one that they would repeatedly use to have the postal service extended to new areas.

In those days before the advent of envelopes, letters consisted of sheets of paper that were folded, tucked in at the ends, and secured with sealing wax. Until the mid-19th century, rates were gauged by distance and the number of sheets being sent. Although most people continued to collect their mail at the nearest post office, a 1794 act did permit home delivery at the cost of two cents extra in postage for each letter. Payment of postage fell to the one receiving the mail on a cash-on-delivery basis, rather than to the sender.

19th CEntury Expansion

By 1800, when the federal government moved its operations from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., the postal system had expanded as far west as Vincennes, Indiana, and had grown to include 903 post offices and almost 21,000 miles of post roads. Even so, it took only two small wagons to move all postal records and equipment from Philadelphia to the new capital city.

In 1829, President Andrew Jackson removed the Post Office from the Treasury Department and appointed former Kentucky Sen. William T. Barry as the first postmaster general with cabinet rank. It was a political appointment that changed the entire character of the postal system, since the Post Office Department soon became the chief dispenser of political patronage for the party in power, a problem that existed until major reforms in this century.

Prior to Barry’s appointment, the nation’s westward movement had brought calls for new post roads and expanding service that consumed the Post Office’s surplus revenue and left the once-profitable system with a deficit. Although Barry had not created this problem, he found himself under constant attack from disgruntled congressmen who saw an opportunity to discredit the Jackson administration. Barry’s limited talents as an administrator and his reluctance to take a hard stance with the administration made him an easy target. At the same time, congressmen eager to please constituents continued to authorize new post roads that added to the postal system’s financial burdens.

Postal Corruption and Confusion

Meanwhile, the awarding of contracts for transporting the mail by various methods also became — until the last quarter of the twentieth century — a target for political dispensation, as the system and Congress moved swiftly into subsidizing and helping to develop various forms of transport.

Stagecoach lines, the first public conveyances used to move the mail, often ignored the stipulations of their contracts, giving priority to the more profitable passenger traffic, by-passing post offices without stopping to pick up the mail, failing to adhere to schedules, and sometimes even abandoning mail sacks beside the road when space was at a premium. Postmasters general took measures to curb such abuses, and by 1830 stagecoaches transported the mail throughout the settled regions of the expanding United States.

Even then, the development of railroads and riverboats threatened the stagecoach’s prominence. The waterways had carried mail in the late-18th and early-19th centuries on the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, and now steamboats were transporting mail where post roads didn’t exist. In 1823, waterways were made official postal routes.

Taking on the Railroads

As the railroads extended across the country, they became increasingly important to the postal system. Mail going from Washington, D.C., to New York City by rail took only 16 hours — far less than by coach. But, secure in their monopolies, the railways charged high rates for moving the mail, some companies asking up to $300 a mile per year, more than three and a half times the amount Congress had authorized the postmaster general to spend. And, in addition to imposing high rates, railways refused to set schedules to allow the transfer of mail from one train to another or to stagecoaches for speedy movement to its destination.

In 1838, Congress designated railways as official mail routes, a move that prompted a mixed reaction from railroad companies. Some jumped at the opportunity and linked various routes together to provide reliable transportation of mail and passengers day and night. But others balked, claiming they could make more money hauling pig iron than mail.

By 1844, enterprising entrepreneurs came to realize the railroads’ potential to move goods quickly over long distances and began setting up express companies that would carry letters and packages at rates cheaper than those charged by the Post Office. Critics of government looked to the success of the express companies as proof of the superiority of the private sector in business matters and called for an end to the Post Office’s monopoly.

Congress, unwilling to dismantle the Post Office that had long been seen as an essential element in tying the vast country together, took action in 1845 to impose harsher penalties for violations of the monopoly. The same legislation classified railroads according to the amount of mail they carried and the speed with which they brought it to its destination.

CHeaper Stamps

To lure back customers from private carriers, Congress also lowered postal rates and in the process eliminated the complicated rate structure that governed mail within the country. Cost now would depend on the weight of the letter, not on the number of pages, and Congress reduced from five to two the number of distance zones into which the country was divided.

A realization by Congress that the Post Office could not be expected to pay its own way, especially when having to meet the needs of a growing country, led to further reductions in postal rates, so that by 1851 it cost only three cents to mail a letter 3,000 miles if prepaid, and five cents if mailed collect.

The impetus given to westward migration by the discovery of gold in California in 1848 greatly increased the demand for mail service to America’s western settlements. Mail could be carried west by overland routes or by ship around Cape Horn, but neither alternative was quick nor without danger.

In 1850, monthly overland mail delivery by stagecoach west of the Missouri River linked Independence, Missouri, with Salt Lake City, Utah. Eight years later, a stagecoach reached St. Louis, Missouri, after a 23-day trip from San Francisco. The mail was transferred to a train for transport east, making the shipment the first overland mail service connecting the two coasts.

Civil War Mail

The beginning of the Civil War, with the attendant disruption of overland travel, brought new problems for mail delivery. But, within the northern states, the U.S. Post Office coped fairly well; in fact, service improved in some areas. The elimination of many unprofitable rural southern routes even helped the Post Office eliminate its deficit.

During the first three years of the war, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair solved the problem of the war’s sudden, huge demands on the mail service by instituting regimental postmasters to handle and forward letters. The Post Office introduced the sale of postal money orders in 1864 to accommodate Union soldiers and others who wished to send money safely through the mail. In addition, Blair shut down unnecessary post offices and spearheaded the drive for free city delivery, a service put into effect in 1863 in 49 urban areas.

A pioneer in attempts to deal with the vitally important international mails, Blair proposed reforms that eventually led to the formation of the worldwide Universal Postal Union. Despite the huge deficit when he became postmaster general, the system had almost broken even by the end of Blair’s term in 1864. A year later it showed a surplus.

Faster Mail, New Problems

A “Fast Mail” service put in place in 1875 used specially built mail cars to allow more efficient handling of mail on trains between New York and Chicago, with other lines soon following suit. Within these cars, agents sorted and distributed the mail en route using pigeon holes or sack racks, depending on the destination. Mail pouches were exchanged with an agent standing at the side of the track, who brought them to the post office for distribution. Special devices such as a catcher arm or crane rigging let agents catch rail mail on the fly.

The railway mail service grew despite its inherent dangers. Usually placed just behind the locomotive, the wooden mail cars were especially vulnerable to fire in the event of an accident. As mail routes expanded and trains traveled at higher speeds, the number of mishaps increased, frequently claiming the lives of mail clerks. A labor union — the U.S. Railway Mail Service Mutual Benefit Association — was organized to promote low-cost life insurance for railway mail clerks and to help focus attention on the unsafe conditions that existed aboard the trains. Despite the union’s efforts, Congress did not mandate all-steel or steel-framed cars until the 1920s.

Recommended for you

Rural Mail

Rural free delivery, like many other innovations in postal service, did not come about easily. Even when Congress finally appropriated funds for rural delivery in 1893, it took some years to put it into practice. Yet in a world without telephones, radios, or television, the mail was the farmer’s only link to the outside world.

In the 1890s, farmers constituted roughly half of the nation’s population. They collected their mail from the nearest post office, as much as a day’s travel away, coordinating the mail run with weekly or monthly excursions for food or supplies. But if country people welcomed RFD, Congress in general did not. Its members deemed the service too expensive and impractical. One member of the House of Representatives reportedly said that mail delivery to farmers would “destroy the rural life of which America is so proud.” Even Postmaster General William Bissell believed such a system would corrupt the country.

Several small, experimental RFD routes began operation in West Virginia in October 1896, and later in 28 specially selected states. By 1899, almost half a million patrons received rural delivery from 630 distribution points in 40 states and one territory.

A special bond of friendship developed between mailmen and their customers along the rural routes, especially in the early days of the service. Isolated country people, grateful for the connection, often met their carriers with cold lemonade in the summer or hot soup in the winter.

An important by-product of rural free delivery was the stimulus it provided for improving roads and highways. After the Post Office turned down hundreds of petitions for rural service due to inaccessible or unserviceable roads, local governments moved to spend money on culverts, bridges, and other improvements.

The Birth of Parcel Post

Although parcel post would seem to have been a logical complement to rural free delivery — especially since private express companies for years had made handsome profits delivering packages that could not be sent through the mail —it took several decades to make the service a reality. The private express companies vociferously opposed government parcel post, as did country merchants who feared losing business. Their forceful arguments against such a service kept Congress in heated debate.

Philadelphia businessman John Wanamaker, who served as postmaster general from 1889 to ’93 and implemented many postal improvements, argued unsuccessfully for parcel post early in his tenure. He received support from the Progressive Party, which wanted the government to take over many private-sector functions. The hard economic times of the 1890s made progressive ideas popular with rural constituents, forcing Congress to take them seriously. But it was not until Wells Fargo and Company, a major express firm, declared a 300-percent dividend to its stockholders in 1913 that public indignation forced Congress to accept that the time for government handling of parcels had come.

An instant success, parcel post had an enormous effect on marketing and merchandising. The Post Office Department handled 300 million parcels in the first six months. Montgomery Ward, which in 1872 became the country’s first mail-order house, now assumed such importance in farm life that its catalog was sometimes called “the homesteader’s Bible.” Sears, Roebuck and Co. began its mail-order operation in 1893, and within five years after parcel post began, Sears’ revenues tripled.

The Weirdest things people sent by US mail

A staggering variety of goods went by parcel post through the years. Farm fresh eggs, a mainstay of the early service, were among the first items sent. Baby chick — not a favorite among carriers due to their noise, smell, and tendency to expire en route — also traveled by parcel post in specially constructed boxes.

In the pre-World War I days, before the practice was banned, even children were sent parcel post. A mother involved in an acrimonious divorce in 1914 shipped a baby from Stillwell to South Bend, Indiana, where its father, who had won custody, resided. For 17 cents, the child traveled in a container marked “Live Baby.” Postal workers saw to its safe arrival.

That same year, the parents of a blonde four-year-old named May Pierstroff sent her from Grangeville, Idaho, to her grandparents in another part of the state for 53 cents, the going rate for mailing chickens. May, who rode in the mail car with postage stamps attached to her coat, was safely delivered by a mail clerk. Word of her excursion soon prompted the Post Office Department to forbid sending any human being by mail.

In 1916, an entire bank — probably the largest object ever sent by parcel post — was dismantled and shipped from Salt Lake City, Utah, to Vernal, California. Its 80,000 bricks were shipped in 50-pound lots, one ton at a time. While the shipments saved the cost of wagon freight, they caused untold headaches and back strain for local postmasters and railroad workers. Too late to stop that shipment, the postmaster general decreed that henceforth a single shipper could post no more than 200 pounds a day.

Some postal customers have entrusted treasured belongings to the Post Office. The world-famous Hope diamond arrived safely at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., after being sent from New York City by Harry Winston, its owner, in an ordinary brown package, insured for $1 million.

The Beginning of Air Mail

If RFD and parcel post were slow in coming to the Post Office Department, so also was its use of the airplane to carry mail. In 1910, Congressman Morris Sheppard of Texas introduced a bill in the House of Representatives instructing the postmaster general to study the feasibility of using airplanes to ferry mail between the nation’s capital and another city. Sheppard’s bill died in committee, but aviation had already captured the interest of Frank H. Hitchcock, the postmaster general at the time.

In September 1911, Hitchcock authorized the first official mail flight by airplane within the United States to take place during an aviation meet on New York’s Long Island. On that occasion, Earle Ovington flew his cargo of letters and postcards from Garden City Estates five and a half miles to the neighboring community of Mineola. Although Hitchcock continued to promote the use of aviation for delivering the mail by authorizing similar flights during other meets, it was several more years before Congress authorized funds for air postal service.

In 1918, Congress appropriated $200,000 over two years for the establishment of experimental, scheduled airmail service between the District of Columbia and New York or Philadelphia. The Post Office called for bids to build five planes, but their production was put on hold when the Army Signal Corps offered the services of its pilots to fly the mail in military aircraft as a way to provide the aviators experience in cross-country flying.

Early pilots were a daring if not reckless lot. They flew without instruments, radios, or navigational tools, and safe landing sites were few and far between. Run-ins with houses, chimneys, and trees were common. One flier who crashed into a tree reported that he had delivered the mail to a “branch” office.

Due to the pilots’ need for visual references on the ground, planes carried mail only in the daytime. In order to make night flying possible, the Department installed radio stations at flying fields. In February 1921, mail was flown for the first time by day and night from San Francisco to New York.

With this accomplishment, Congress finally recognized the potential of air postal routes and appropriated $1.25 million to expand the air service by installing more landing fields, towers, beacons, searchlights, and boundary markers across the country. The Post Office also began fitting airplanes with luminescent instruments, parachute flares, and navigational lights. During the 1920s, the Post Office received special awards for its contribution to the development of aeronautics and aviation.

Commercial airlines began to carry the mail in 1926, and soon the Post Office initiated the transfer of its lights, radio service, and airways to the Commerce Department. Terminal airports, except for Chicago, Omaha, and San Francisco, were transferred to local municipalities. By 1927, all airmail was carried under contract.

A Modern Post Office

The introduction of regular airmail service in 1918 rendered the U.S. Post Office system complete. The task of accommodating the nation’s vast geographical area and a growing population during an era of significant developments in transportation had been accomplished, leaving the department with the job of improving and refining the existing structure. However, as Americans gained greater access to the world around them through the telephone, radio, and then television, they tended to worry less about the quality of their postal service. Since congressmen did not hear complaints from their constituents about the postal system, they focused their attention on other issues.

One persistent area of complaint, however, involved the Post Office Department’s use of patronage in hiring and promotion. The Pendleton Act, passed in 1883 following the assassination of President James A. Garfield by a disappointed job-seeker, established the Civil Service Commission and laid down rules for gaining government employment. But the Post Office seemed unable to separate itself from the patronage system entirely.

Other labor problems manifested themselves as well. Postal workers earned considerably lower wages than other government employees. And as the volume of mail increased, workers worried that they would lose their jobs to machines that could more quickly and efficiently handle the greater load.

In October 1966, concerned workers caused a virtual shutdown of Chicago’s post office, the world’s largest postal facility. Service was paralyzed, management authority broke down, and millions of cross-country letters and parcels were delayed for weeks. The emergency led Postmaster General Lawrence F. O’Brien to urge publicly that the postal service be removed from the president’s cabinet and converted into a non-government corporation. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed a commission to determine if the current postal system was “capable of meeting the demands of our growing economy and an expanding population.”

The commission’s four-volume report on its findings predicted a deficit of $15 billion within the next 10 years if action were not taken. The Post Office today, the commissioners said, was a business and should operate by the revenue it generates.

President Richard M. Nixon and his postmaster general, Winton M. Blount, were also committed to postal reorganization and incorporated their reforms into the Postal Service Act of 1969. Congress took no action on the proposed legislation, although it had a spirited debate on the idea of separating the Post Office from the executive branch, with those representing rural areas most inclined to keep the department under governmental control.

Finally, in August 1970, Congress sent the Postal Reorganization Act to President Nixon for his signature. Under this legislation, the Post Office Department became an independent agency directed by a nine-member board of governors. This board would appoint the postmaster general and deputy postmaster general for day-to-day administration of the service. The new United States Postal Service received a distinctive insignia, a host of obligations, and a future, like the history of its predecessor — the U.S. Post Office Department — filled with innovation and change.

The familiar quotation inscribed on the post office building in New York City — “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds” — was never, as many believe, the official motto of the Post Office Department. Adapted from the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century B.C., the words nonetheless suggest the determination to overcome problems that has characterized the monumental efforts to move the mail in the United States since the establishment of the Post Office Department by the Second Continental Congress in 1775.

Cathleen Schurr resides in Maryland and is the author of several previous articles in American History.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.