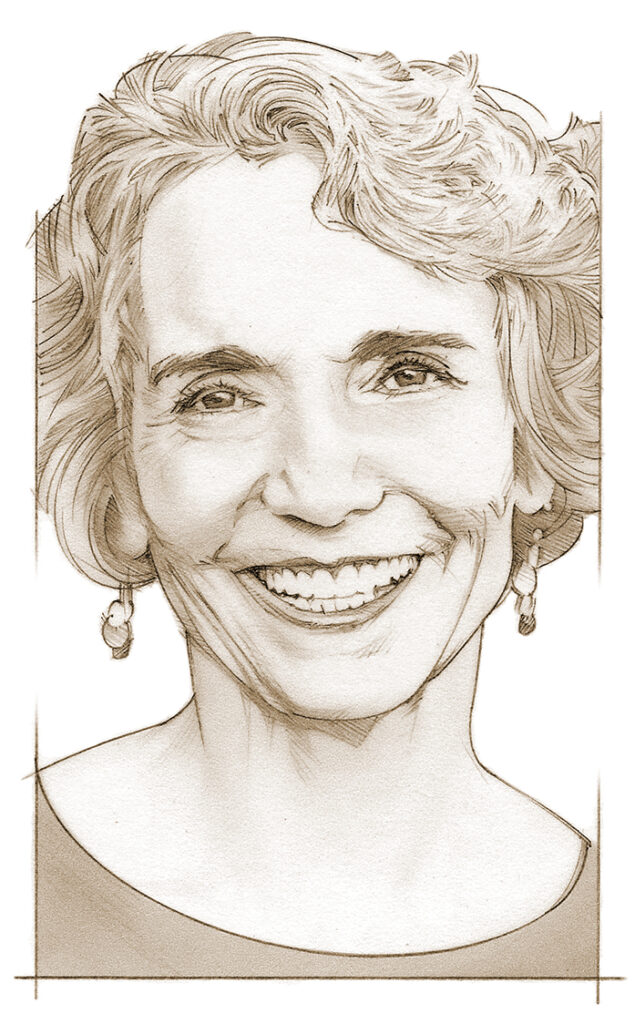

With her book The Hello Girls and a follow-up documentary film, historian, commentator and author Elizabeth Cobbs set out to recognize the women who served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps’ Female Telephone Operators Unit during World War I. Members of the unit, many of whom worked Stateside as switchboard operators, maintained communications on the Western Front under spartan and sometimes hazardous conditions. Despite having served in uniform, however, the Hello Girls were denied veteran status. Though Congress remedied that in 1977, many of them had died by then. Recently lawmakers introduced legislation to formally honor the unit with the Congressional Gold Medal, presented for distinguished achievements that have had a major impact on American his-tory and culture. Past recipients include notable American warriors and military units. Cobbs recently spoke with Military History about her book and why the Hello Girls are deserving of recognition.

Who were the ‘Hello Girls’?

They were a group of 223 young women—some in their teens, most in their 20s and a few “old women” in their 30s—who volunteered at the request of the U.S. Army to go to France and run the telephone system. This was a daring thing. Most soldiers hadn’t even gone yet. These women were in logistics. The Army needed telephone operators over there before the majority of doughboys. They had to facilitate what was happening at the front, to get supplies, to get troops shipped here and there. Some served as long as two years. These women fielded 26 million calls for the Army in France. A handful traveled with General [John J.] Pershing during the big battles of Meuse-Argonne and Saint-Mihiel. Others served at the headquarters of the American First Army, which was close to the front but not in the war zone. They came from all over—from Washington state, down to Louisiana, up to Maine, even Canada. There were some French-Canadian women who volunteered and served with the U.S. Army.

Many served close to or on the front lines. Were any killed or wounded?

None were killed in action, but some did suffer permanent injuries, mostly from tuberculosis, which was common in northern France. Two died from the influenza pandemic, one on Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1918.

The conditions of World War I were pretty difficult, especially related to the weather these women had to endure in fairly exposed accommodations. Some were under bombardment. Some were in buildings where artillery concussions blew out windows. Once, they were told to evacuate but wouldn’t leave until the soldiers had. These women worked around the clock, especially the supervisors. Chief Operator Grace Banker, who led the first unit, recorded in her diary at the start of an offensive, “I slept two hours today.” They were handling incredibly complex logistical problems near the front lines. They got no breaks; they worked seven days a week, 12-hour shifts for several months during the worst part of the American war effort. It was extremely stressful. Some were close enough to the front lines that their switchboards shook during bombardments.

Of course, these women crossed the ocean to get to Europe in the first place. This was a time when troopships were being sunk. All of these women knew about this, and they were constantly told to use their lifejackets as pillows and wear all of their clothes to bed in case they were torpedoed. It was scary.

What kind of training did they receive?

They went through a very strict recruitment and training. They had to be bilingual in French and English, and many washed out because of that. In fact, 7,600 women applied for the first 100 positions. Many were cut for language reasons, others because they weren’t fast enough on the phone. Once selected, they were vetted extremely carefully, sometimes three and four times, by Army intelligence. These women were literally handling national secrets in the wires they connected. One woman was even pulled off a ship at the last minute, though she turned out to not be the German spy they feared she was.

Once selected, they were trained by AT&T [American Telephone and Telegraph] on the phone system. After that they were sent to New York City, where they were drilled and learned to salute on the rooftop of AT&T headquarters. Once they went to France, the women who were sent toward the front were trained in the use of gas masks and pistols. They wore uniforms and had dog tags; otherwise, they risked being executed as spies if captured. They were told again and again that their uniforms and dog tags were their protection as soldiers of the U.S. Army.

Many were bilingual. How important was that skill?

The first group of 100 female volunteers were all required to be absolutely fluent in French and English. They had these super strict tests, where they had to simultaneously translate and operate a telephone exchange, record everything correctly and communicate accurately under pressure. It’s hard for us to appreciate today how nerve-racking that could be. They were getting hundreds of calls an hour, all of them critically important, truly a matter of life and death. These women felt a great deal of responsibility. They were connecting all kinds of calls, such as between commanders and combat units in the field. There were times when they were even talking with French combat troops. The Army set up its own PBX [private branch exchange] telephone system for communications to and from the front. However, the women often had to connect with French lines and French toll operators. Back then, a toll call would be passed from operator to operator to operator. This was a problem for the American doughboys, who generally did not parlez-vous. Pershing realized he couldn’t get a call to go anywhere, so that’s when they realized they needed people who could do the job and communicate with the Allies at the same time.

Why were women selected as operators?

The Army found it took men 60 seconds on average to connect calls that women connected in 10 seconds. In wartime that was the difference between life and death—for an individual and sometimes for whole battalions. Women were adept at using this technology and had the ability to do it much faster and more reliably than men. They were tested on being able to place calls in two languages, write and convey messages, make life-and-death connections in an instant, all while maintaining their composure and decorum.

Banker received the Distinguished Service Medal. What did she do to earn such recognition?

Chief operator for the Signal Corps, Banker was a remarkable person who was devoted to the American cause during World War I. She led the first female contingent under very challenging and difficult circumstances. At one point she developed a severe allergic rash. A doctor told her she needed to have it taken care of, but she said she didn’t have time. There’s a photo of her in which she looked absolutely terrible. Grace served under the extraordinarily demanding conditions of the Battles of Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne and was recognized for courageous service. In World War I the U.S. Army awarded only 18 Distinguished Service Medals to Signal Corps officers, of whom 16,000 were eligible. All the honorees were listed by rank. She was listed as “Miss,” because she was a [single] woman.

Why did the War Department deny the ‘Hello Girls’ veteran status?

Their commanding officers begged and pleaded with the War Department to recognize these women who had served alongside them, some in very dire circumstances. Around 11,000 women served with the Navy and Marines during World War I, and every one of them got military benefits, including hospitalization for disabilities. They all served at home in the United States. Only the Army sent women across the ocean into harm’s way, and then denied them veteran status. It was so upsetting and maddening for these women. They were told it would lessen the importance of the meaning of “veteran” if they were to grant women this honor. The Army decided early in the war these women would be contract employees. However, they neither told the vast majority of women, nor gave them any to sign. In fact, women took the same soldier’s oath everybody else did. They wore uniforms but were unaware there was a distinction. Many of the women were flabbergasted when they arrived home and found out they weren’t veterans.

Congress finally recognized them as veterans in 1977. How did that come about?

Their recognition came on the same legislation as the WASPs [Women Airforce Service Pilots], introduced by Senator Barry Goldwater. Goldwater had also been a service pilot in World War II and couldn’t believe that women he’d served with, many who wore the same uniform as him, were not being given veteran benefits. At that time the women of World War I came forward and said, “What about us?” The legislation then covered both groups.

Why award the Hello Girls the Congressional Gold Medal after so many decades?

Because it’s a story that was lost. I’ve met so many women in the Army who’ve said they had no idea this is where their story began. Women today represent 15 percent of the armed forces. It’s a very brave act for any woman to join an organization in which she is going to be in the distinct minority and going against gender expectations. It’s important to say we value female veterans as much as we value male veterans. The Congressional Gold Medal would help all Americans better appreciate the women in our armed services. It would help us recognize that what the Hello Girls did was not only physically courageous, but morally courageous—challenging every social convention at the time in order to help our country. It took a very special person to do that. They performed a heroic service.

This interview appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.