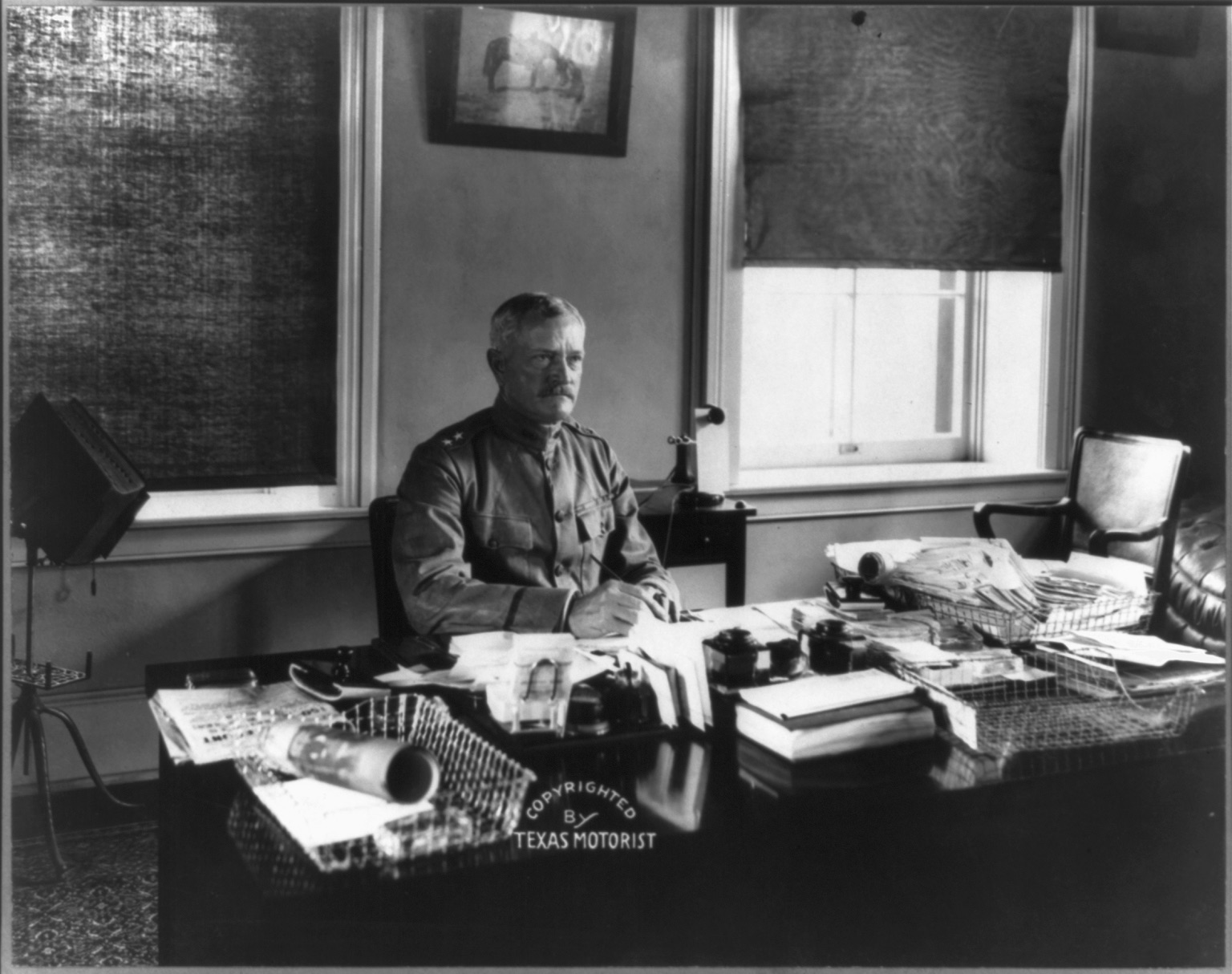

General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of American forces in Europe during World War I, is an enigma. In photographs he appears as distant as a Roman statue, lacking the evident charisma of leaders like Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Troops who met Pershing on the parade ground often found him uninspiring.

Pershing’s critics have derided his inflexibility. His insistence that American soldiers should abandon the trenches and adopt open warfare tactics appears naive in retrospect. As a result, his troops had to relearn lessons the French and British had learned in 1914, at a high cost in American lives. Pershing implicitly acknowledged his shortcomings as a battlefield commander when he turned over command of the American First Army to General Hunter Liggett in October 1918, in the midst of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Had it not been for Pershing, however, there might have been no U.S. Army to command in the first place.

After the United States entered the war in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker decided to work toward establishing an American army that would operate under American commanders on its own section of the Western Front. Baker instructed Pershing to realize this goal despite anticipated opposition from the French and British.

Success depended entirely on Pershing, as he would have to negotiate with France’s Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who from the spring of 1918 held overall command of the Allied forces. The going was not easy. Both France and Britain had suffered catastrophic losses during the war, and their manpower reserves were low. Desperate for replacements, they sought to incorporate American soldiers into French and British formations as they arrived. That concept became known as amalgamation.

To the Europeans amalgamation made perfect sense. Thanks to American unpreparedness, the Doughboys lacked both heavy equipment and training. Europeans could provide equipment such as artillery, tanks and aircraft. Training, however, would be a lengthy process conducted under American officers with scant experience of combat. Germany had gambled on slow U.S. military mobilization, first by initiating unrestricted submarine warfare and then by launching an all-out offensive on the Western Front that continued through the spring and summer of 1918. The race for supremacy depended on how quickly the Americans could get to the front. Trained by European officers and fighting alongside experienced European troops, insisted the French and British, the Americans could enter combat more rapidly and effectively.

Pershing saw amalgamation differently. Proximity to French and British soldiers, he believed, would lower the Doughboys’ morale and contaminate them with outmoded notions of warfare. Under European direction they would skulk in trenches and grow dependent on artillery and machine guns rather than on their rifles and will to victory. Ultimately, the Doughboys would be cannon fodder for unimaginative European generals.

There was also the question of pride. Fighting under European flags, Americans would not feel a personal commitment to the cause for which they risked their lives. American field and staff officers would fail to grasp the art of command. Perhaps more important, credit for victory over Germany would go almost entirely to France and Britain, relegating the United States to a mere footstool at the postwar negotiating table.

Pershing’s battle to resist amalgamation lasted almost throughout the war and called upon every ounce of his determination and willpower. Foch and British Field Marshal Douglas Haig were tough negotiators who drew back only reluctantly from their initial proposals to disperse American soldiers in European formations. They eventually conceded that American regiments or divisions might fight as intact units, but only in European corps and armies.

Pershing compromised when necessary in the challenging spring and summer of 1918 but remained inflexible in pursuit of his ultimate goal. At times he and Foch came close to exchanging blows. Pershing finally managed to form the U.S. First Army in August 1918, but Foch refused to give up. He tried to curtail independent American operations, and even sought to break up the American offensive in the Meuse-Argonne after it had gotten under way. Pershing’s refusal to back down bolstered national pride and ensured Wilson an important role in postwar negotiations at Versailles. It also provided American officers and men with opportunities to learn their own lessons in combat—albeit at a bloody cost. It was worth the struggle, for lessons acquired in this war would save lives in the larger war to come.

Originally published in the September 2013 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.