As Major Paul A. Putnam landed his F4F-3 Wildcat fighter on Wake Island, a small horseshoe-shaped atoll 2,000 miles west of Pearl Harbor, he was surprised to see dozens of cheering Marines and civilians lining the runway. The commander of Marine fighter squadron VMF-211, Putnam had arrived with 11 other Wildcats—rugged aircraft armed with four .50-caliber machine guns and capable of carrying a pair of 100-pound bombs. They were Wake Island’s first fighters, and personnel on the island were overjoyed to finally have some aerial protection. “Nothing much was lacking but the strip of red carpet,” recalled Major Walter L. J. Bayler, a Marine communications officer.

If the lively reception instilled any optimism in Putnam’s mind, it quickly faded when he climbed out of the cockpit and looked around. His new home was “far less advanced in construction than had been anticipated,” he wrote—a relatively kind description for what lay before him.

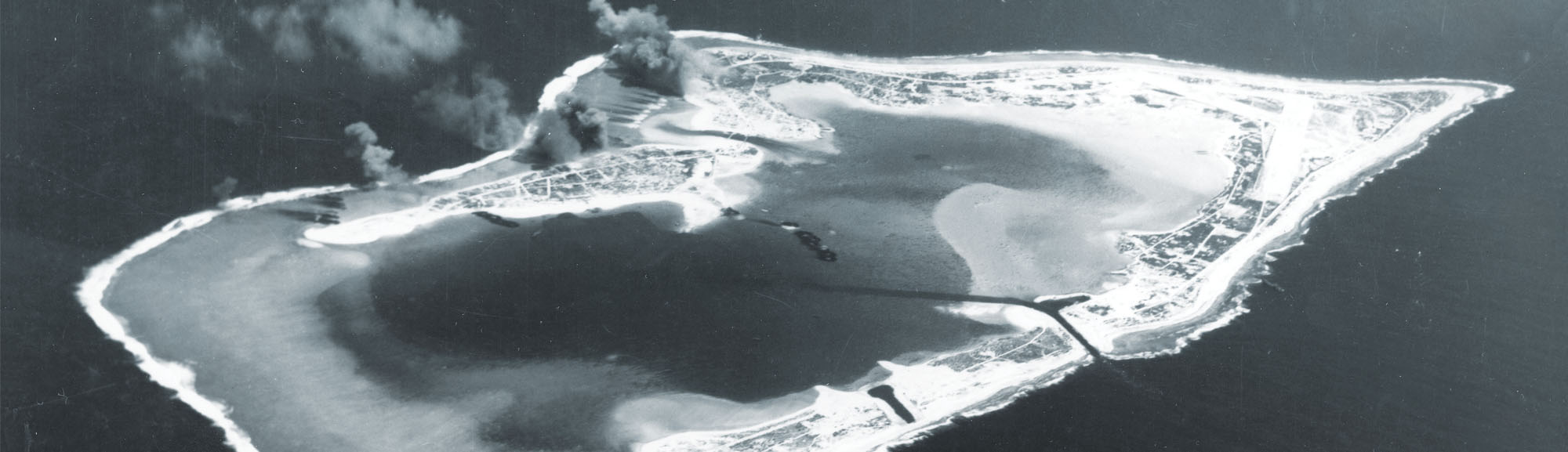

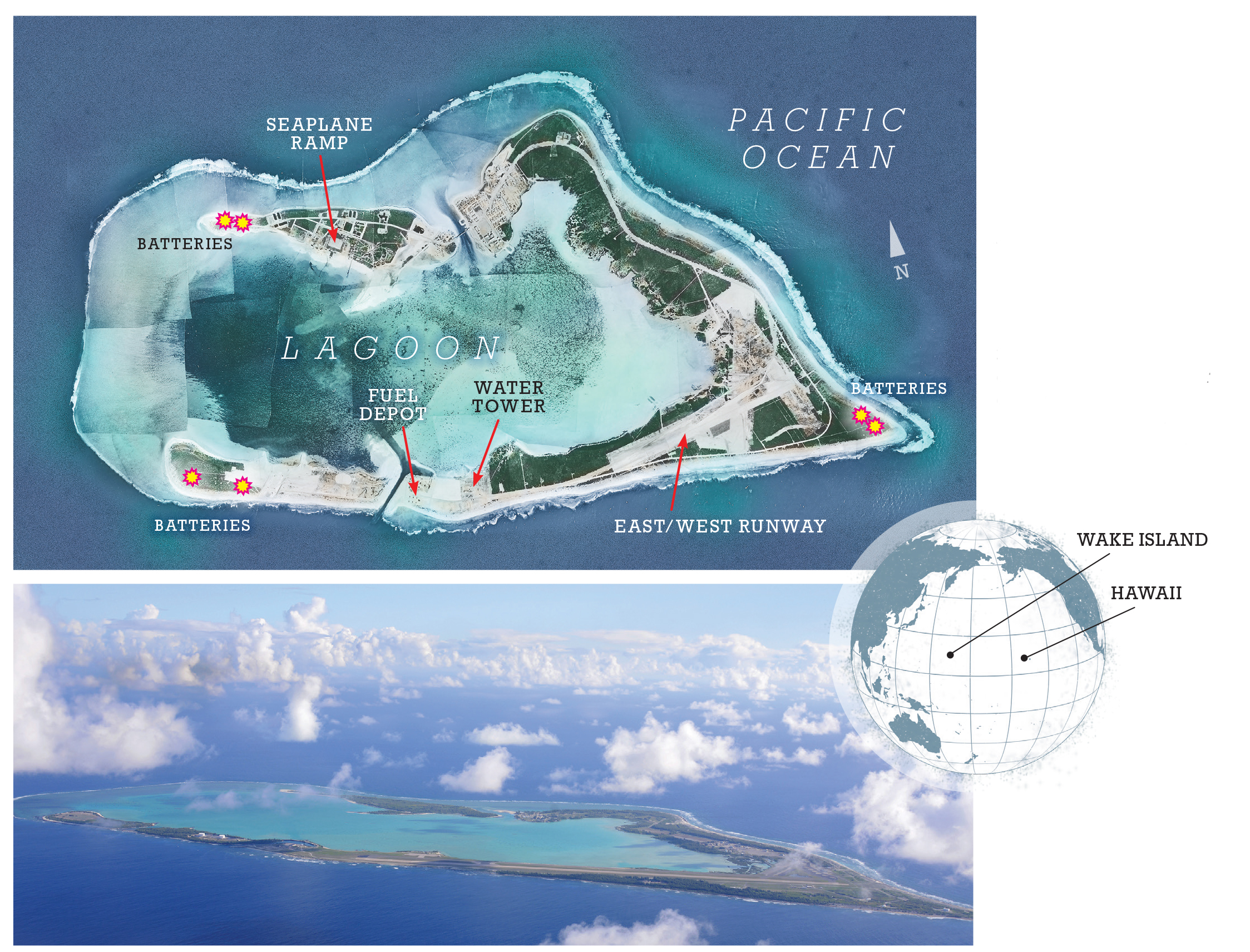

As of December 4, 1941, the day VMF-211 arrived, Wake Island was a work in progress. It lacked radar to warn of approaching planes, relying instead on a lookout with binoculars atop a 50-foot-high water tower. The island’s crushed-coral airstrip was too narrow to allow more than one plane at a time to take off—a major problem if Putnam’s squadron had to get aloft in a hurry. There were no bunkers to camouflage and protect planes on the ground, and most of the aviation fuel was stored above ground, vulnerable to attack. It would take lots of hard work, plenty of time, and a bit of luck to whip the island’s air defenses into shape.

Putnam was a good man for the job. Born in Michigan in 1903, he had joined the Marine Corps in 1923 after dropping out of Iowa State University. He was commissioned in 1926 and became a fighter pilot in 1928. At five foot nine, he fit comfortably in the cramped cockpit of a fighter plane, flying combat missions in Nicaragua in 1931-32. Longtime colleagues described the married father of three as “able, level-headed, cooperative.”

Patient demeanor or no, time was not on Putnam’s side. A week earlier, Washington had warned that “an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days”; Putnam knew Wake was sure to be high on Japan’s target list. Closer to the Japanese-held Marshall Islands than to the American bases on Guam and Midway, Wake Island was barely a speck in the western Pacific. But from its shores, American long-range patrol planes could monitor enemy bases, while fighters and bombers would threaten Japanese advances in the region.

In 1940 Congress accordingly appropriated $7.5 million to convert Wake Island into a modern naval air station. By late 1941, more than 1,100 civilian construction workers were on the island, laying roads, dredging the lagoon and channel, erecting barracks and other buildings—but their work was far from being finished.

Navy Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, in charge of all naval activity on the island, eagerly awaited the completion of facilities for ships and aircraft. Otherwise, he only had a force of 378 Marines—less than half a normal defense battalion, led by Marine Major James P. S. Devereux—to cover and protect 20 miles of shoreline.

So on November 27, 1941, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, ordered Major Putnam to pick his 11 best pilots and 12 of his unit’s new Wildcats for an urgent mission. Putnam had to keep their destination secret, so he told his men it was a routine training exercise. Taking only their razors, toothbrushes, and the clothes on their backs, the 11 pilots left Hawaii and flew to the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, already at sea, for the trip.

Since Kimmel’s orders were vague, Putnam sought clarification from Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, head of the Enterprise and the task force. “I’m completely in the dark,” Putnam said. “I’m on my way to Wake. What in hell am I supposed to do when I get there?”

“Do what seems appropriate” was Halsey’s zen-like answer.

The Enterprise’s sailors treated the Marine fliers like gold, and navy mechanics made sure the Wildcats were in tip-top shape. “I feel a bit like the fatted calf being groomed for whatever it is that happens to fatted calves,” Putnam wrote to a friend, “but it surely is nice while it lasts.” Navy fliers aboard ship even gave Marine pilot Lieutenant John F. Kinney a bottle of scotch as a parting gift, saying he would need it more than they would.

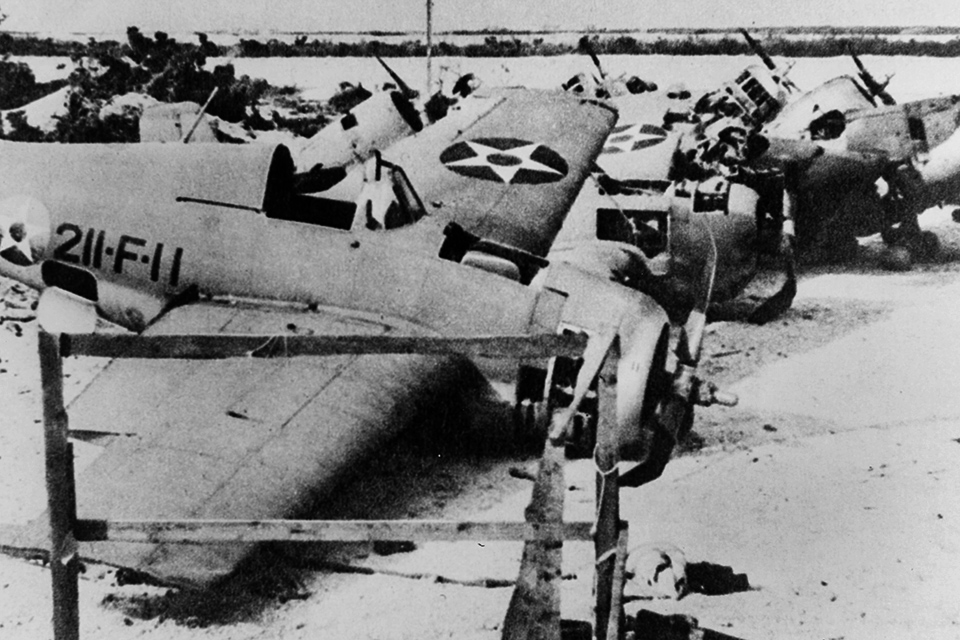

On December 4, 1941, VMF-211 took off from Enterprise and landed on Wake to the cheering reception. Once settled in, Putnam worried about what he could offer beyond the Wildcats. None of his pilots had more than 20 hours of flying time in the new fighters. His ground crew of about 40 Marines had arrived two weeks earlier, but unlike the navy mechanics aboard Enterprise, none had worked on a Wildcat. They had no spare parts—not a tire, spark plug, nor even a manual.

Out of necessity, Putnam and his men became masters of improvisation. Although the Wildcat could carry ordnance, the bombs on Wake were configured for Army Air Forces aircraft and did not fit the navy fighter. Putnam’s men therefore rigged their planes with a “lash-up” system; it was not the safest method, but it seemed to work. There was also a short supply of oxygen tanks that were vital for high-altitude flying. So they engineered a dangerous but effective way to transfer pressurized oxygen from the contractors’ welding tanks to smaller tanks carried in the aircraft.

Putnam named Lieutenant Kinney his engineering officer, promising him “a medal as big as a pie” if he kept the planes flying. Privately, Putnam doubted that Wake could ever be a viable air base. “It was not worth its weight in sand,” he said. “It was too doggone small; it wasn’t big enough to operate off of.”

Putnam’s most pressing need was bunkers to shelter his planes. Told the job would take weeks, he exploded: “I want things now!” He stressed “speed, rather than neatly finished work,” so he was shocked that afternoon to spot a civil engineer and surveyors deliberately plotting sites with peacetime precision. “It required an hour of frantic rushing about and some very strong language,” Putnam said, to replace the young civil engineer with contractors and bulldozers. They promised to finish the bunkers by 2 p.m. on December 8.

Major Bayler, who had known Putnam for years, was stunned by the commander’s reaction. “I’ve never in my life seen a man change so completely,” Bayler said. “He acquired a new personality overnight.” The reserved, soft-spoken peacetime officer gave way to an “iron-jawed commander of a hard-fighting outfit, forceful, energetic, and resourceful” and “beautifully articulate in any situation that called for strong language,” Bayler said.

AT 6:50 A.M. ON DECEMBER 8—December 7 in Hawaii—their time and luck ran out. Wake Island’s denizens heard the frantic radio message that Pearl Harbor was under attack. Putnam ordered four Wildcats to be in the air at all times, with the other eight fighters ready to take off at a moment’s notice. With the bunkers still unfinished, the Wildcats, as usual, sat in the open about 100 yards apart.

At 11:58 a.m., Putnam, who had flown the dawn patrol, stepped out of his command tent, looked up, and felt his blood run cold. Bombers were approaching from the south—and they were not American. Putnam yelled a warning and sprinted toward the nearest foxhole. In high school, he had run the 100-yard dash in 10.2 seconds—but he swore he broke 10.0 that day.

He watched as 18 G4M Betty bombers came in at 2,000 feet and in only 10 minutes turned the airstrip into “a slab of hell” with bombs and gunfire. Frustratingly, VMF-211’s four-Wildcat patrol was north of the island at 12,000 feet; the pilots were not even aware of the low-level Japanese attack to the south.

Grazed by a bullet and dazed by blast concussion, Putnam moved around—looking like “a man walking aimlessly in his sleep,” Major Bayler recalled—to assess the damage as soon as the attack was over. Seven of the eight Wildcats on the ground were blazing wrecks, reduced to only spare parts; the eighth was badly damaged. Of his 55 pilots and ground personnel, 23 were dead and 11 wounded. The island’s above-ground fuel tanks were a raging inferno. The airstrip itself, however, was untouched: the confident Japanese had spared it for their own use.

Major Devereux cursed the lack of radar, which had been promised to him weeks earlier. With it, he felt that Putnam might have gotten all 12 of his fighters in the air to meet the attack. Putnam himself, however, did not make any excuses, saying that his squadron had been “unprepared in every particular.”

Commanders on Wake knew the enemy would attack again, but without radar, they could only guess when the next raids would occur. Putnam calculated that the Japanese planes taking off from the Marshall Islands at dawn would arrive over Wake at around 11 a.m., so for the next two days, VMF-211’s four fighters were already aloft and waiting. On December 9, 27 Mitsubishi G3M Nell bombers attacked; Putnam’s men shot down one of them. The next day, Captain Henry T. Elrod shot down two, earning the nickname “Hammering Hank”—but the squadron’s best was yet to come.

Shortly after midnight on December 11, Marine lookouts spotted Japanese ships on the horizon: a flotilla of cruisers, destroyers, and transports set to land troops. Though battered, Wake still had formidable firepower: three batteries of five-inch artillery guns, salvaged from old battleships.

Devereux held their fire until the Japanese ships came well within range, while Putnam’s Wildcats circled above at 15,000 feet, ready to attack. At 6:15 a.m., when the ships were only 4,500 yards away, the Marines opened fire. Shells tore into the light cruiser Yubari, sank a destroyer, and damaged two others.

Realizing the Japanese warships had no air cover, Putnam radioed his wingmen: “Let’s go down and join the party,” and they streaked through thick antiaircraft fire. Putnam dropped two bombs, narrowly missing a destroyer, and fired his four machine guns at another, seeing a “rainbow from shattered glass” as his .50-caliber bullets raked its bridge. One of Captain Elrod’s bombs hit the destroyer Kisaragi’s stern, where its depth charges were stored; the resulting series of explosions sank the ship.

The Marine fliers landed several times to refuel and rearm before going back for more. In all, they dropped 20 bombs and fired 20,000 bullets. The Wildcats and the island’s shore batteries sank or damaged nearly every Japanese ship in the flotilla. The invasion armada fled—but the squadron had paid a heavy price.

One of the four remaining Wildcats barely made it back, its engine a total loss, and Elrod’s fighter crashed on the beach. As Putnam ran to pull what was left of his buddy from the wreckage, an uninjured Elrod hopped out. “Honest,” he said with tears in his eyes. “I’m sorry as hell about the plane.”

Marine fighter squadron VMF-211 was down to only two airworthy Wildcats.

TO KEEP THE VMF-211 IN ACTION against future Japanese attacks, Putnam needed a sheltered hangar for repair work, an underground bunker for radio equipment, and help with aircraft maintenance. He sought out the civilian workers on the island for assistance; some volunteered, but most hid. Putnam fumed. He asked Cunningham, the island commander, for permission to use “armed force in rounding up labor and seeing to it that they remained on the job.” Cunningham refused, saying with some hyperbole that he didn’t believe their objectives “warranted him authorizing the execution of any civilian whose work might not measure up” to Putnam’s requirements.

Without enough serviceable planes, Putnam thought of other ways to hinder the enemy. Tiny Wake Island was a navigational nightmare to locate from the air, but the Japanese did not seem to have trouble finding it. Putnam and Major Bayler deduced the Japanese had a submarine nearby, broadcasting a homing signal. Putnam told his pilots to watch out for it.

During the evening patrol on December 12, Lieutenant David D. Kliewer spotted a submarine. He dove to attack, dropping his bombs and strafing the sub. Putnam took off in the other Wildcat to finish the job, but found only an oil slick in the water where the vessel had been.

Three days later, Putnam spotted another sub, but confusion reigned. Noting strange markings on the conning tower, he could not positively identify the vessel as Japanese. Cunningham, fearing the sub might be American or Dutch, ordered the Wildcat pilot to hold off.

Meanwhile, Japanese planes continued to attack nearly every day, reaching Wake Island around noon—which Putnam called a “stupid” routine. The predictability enabled VMF-211’s two flyable Wildcats to be aloft and intercept them. Putnam was proud of his men’s resilience in fighting despite the tough odds. “It wasn’t any fun,” he said, “but it was satisfying to find out just how good my boys were.” But then the Japanese changed the game.

ON DECEMBER 21, 47 enemy planes reached Wake Island three hours earlier than usual, around 9:00 a.m. VMF-211 had only one operable Wildcat that day, gassed, armed, and sitting on the runway—a fat target. Putnam was two miles away, conferring with another pilot before the midday patrol. He grabbed the nearest truck and made a mad dash to the airstrip. Japanese A6M Zero fighters made low passes, shooting at Putnam’s racing truck. He zigzagged wildly to avoid the strafing aircraft, twice leaping from the truck to take cover in a ditch. After reaching the airfield unscathed, Putnam jumped into the Wildcat’s cockpit, but at first its balky engine wouldn’t start. It finally fired up—as the attackers departed. Putnam took off and gave chase for 40 miles before giving up. His actions that day earned him the Navy Cross.

As the Japanese continued their raids, Putnam flew as many missions as he could. However, he felt increasingly frustrated by command duties that kept him on the ground, as well as the dearth of airworthy fighters. “He might be outwardly composed,” Bayler said, “but inside he was biting his nails, tearing his hair, and throwing his shoes at the cat.”

By December 22, Lieutenant Kinney and his mechanics patched up another Wildcat, giving the squadron two fighters for what proved to be its last hurrah. At 10 a.m., Captain Herbert C. Freuler and Lieutenant Carl R. Davidson took off to meet the regular midday raid, and 33 B5N Kate bombers along with six Zero fighters arrived on schedule. Freuler and Davidson dove into the Japanese formation despite the desperate odds. Davidson was shot down and killed, but Freuler managed to down two Japanese planes before enemy fire irreparably damaged his Wildcat. He barely made it back to Wake and crash-landed on the beach. Unkmnown to him, however, Freuler had exacted some revenge—a Kate bomber he shot down in flames carried Noboru Kanai, the bombardier credited with dropping the fatal bomb on the USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

With VMF-211’s last two Wildcats out of action, Putnam and his two dozen pilots and ground crew reported to Major Devereux as infantrymen—and just in time.

Shortly after midnight on December 23, more than 1,000 Japanese troops landed at several points across the island, and the final fight for Wake Island was on. It was less an organized battle than a fierce melee between small groups of men. At 3 a.m., Devereux deployed Putnam’s small force to protect a three-inch artillery gun near the beach that was raising hell with the incoming Japanese landing barges.

Upon hearing Devereux’s orders, John “Pete” Sorenson, a muscular 42-year-old pile driver, led a group of about a dozen civilians to Putnam. “We’re going with you,” Sorenson told him.

A civilian labor force was one thing—but Putnam felt the Japanese were likely to execute any civilians fighting alongside uniformed American troops. “You can’t go with us,” he told the volunteers.

“Do you think you’re really big enough to make us stay behind?” Sorenson asked.

“I’m proud of you,” Putnam replied. “I’d be glad to have you as Marines, but take off.” As he led his men forward, the unarmed civilians nevertheless followed along in what Putnam called “humorous defiance” of his orders, appointing themselves ammunition carriers for the Marines.

At dawn, not long after Putnam’s makeshift group set up a position near the artillery gun, Japanese soldiers approached them. Armed with only a .45-caliber pistol, Putnam shot two of them at such close range that one’s helmet clanged against his own. More enemy soldiers attacked. Sorenson rose to meet them, throwing rocks until he was cut down. Elrod managed to momentarily stop the enemy charge, blasting away with his Thompson submachine gun while screaming, “kill the sons of bitches!” Moments later, as he prepared to throw a grenade, he was shot several times and killed.

Putnam’s men fell back to the artillery gun, firing as they went. “This is as far as we go!” he told them. And it was. The Japanese continued their ferocious attacks. As Putnam took cover under the artillery piece’s steel platform, a bullet struck him, passing through his cheek and neck. In the ear-splitting chaos, he did not realize he was hit. He suddenly felt drowsy and did not know why. Then a Marine asked if “it hurt much,” and Putnam discovered his wound. The chin strap of his old M1917 helmet, cinched tight under his jaw, had staunched the blood flow and prevented him from going into shock.

By 7:30 a.m., the island’s commanders, Cunningham and Devereux, knew their battle was hopeless and raised the white flag. A Japanese officer led Devereux around the island, ordering each pocket of resistance to surrender. Putnam’s men were still holding out when Devereux reached them three hours later. Putnam “looked like hell itself,” Devereux recalled, his face “a red smear.”

“Jimmy, I’m sorry,” was all Putnam could mutter, but he was relieved that his “boys didn’t have to shoot anymore.” Nearby lay Elrod’s body, an unprimed grenade still clutched in his fist. For his repeated valor, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

Putnam’s small band had fought as fiercely on the ground as they had in the air, holding off 200 Japanese soldiers until the surrender. The cost, however, was great. Of the 26 Marines defending the position, 16 were dead and nine were wounded. Of the 14 civilians with them, eight lay dead. While Putnam had complained earlier of civilians shirking their responsibilities on the island, those who fought alongside his Marines earned his undying gratitude. “No mere words can ever express what is owed,” he said.

Putnam and VMF-211 had more than earned their pay. “The performance of these pilots is deserving of all praise,” Cunningham said. “They have attacked air and surface targets alike with equal abandon.” Always facing overwhelming odds with no more than four patched-up and sometimes barely-airworthy fighters, the squadron nevertheless claimed eight Japanese bombers, three fighters, one seaplane, a destroyer, and a submarine. Cunningham singled out Putnam for additional praise, writing that his conduct “was of the highest order of courage and resolution.” Putnam’s men agreed. His “cool judgment, his courage, and his consideration for everyone,” Kliewer asserted, “forged an aviation unit that fought behind him to the end.”

Along with the rest of the Wake Island Marines, Putnam spent the remainder of the war in POW camps in China and Japan. Like many underfed and malnourished POWs, he dreamt of food. While in the camps, he handwrote a 75-page cookbook of his favorite recipes, called Glimpses of Heaven as Seen from Zentsuji (Prison Camp). He took great pride in the good morale of his Marines. “They were sorry to be there but they weren’t ashamed of being there. I wasn’t, either,” he said. He was liberated in September 1945 and stayed in the Marine Corps, retiring as a brigadier general in 1956. He died in 1982 at age 78. ✯

A Most Unlucky Man

A Most Unlucky Man

Luck was in short supply for Americans on Wake Island—most strikingly so for Herman P. Hevenor. In 1941 the U.S. government sent the experienced engineer to examine its construction projects across the Pacific. Traveling in style on Pan American Airways’ Philippine Clipper, a Martin M-130 flying boat, Hevenor reached Wake on December 7, 1941 (December 6 in Hawaii).

The next morning, men on Wake received news of the Pearl Harbor strike; Japanese bombers attacked the island a few hours later. The Clipper, lucky to survive with only a few bullet holes, was rescheduled to depart to Midway—with a seat reserved for Hevenor. In the confusion, however, the engineer did not arrive in time. The Clipper’s pilot took off without him—a “rather drastic lesson in the wisdom of punctuality,” recalled island Marine commander Major James P. S. Devereux.

Hevenor survived enemy air attacks over the next few weeks. On December 20, three days before the island fell to the Japanese, a U.S. Navy PBY patrol plane arrived with mail and orders for the island’s commanders. This time Hevenor was ready and waiting—but was bumped by Major Walter L. J. Bayler, who had priority orders. The PBY had plenty of room for both Bayler and Hevenor, but navy regulations required all air passengers to wear a parachute and a life vest. Bayler had taken the last of them. Hevenor was captured when Wake Island surrendered. He remained a prisoner until September 8, 1945.

The government retroactively paid Hevenor his salary for his time as a POW, but his 1941 travel orders had allotted him a $6 daily allowance. Hevenor believed he was due that sum for his 1,355 days in captivity. The total came to $8,130—nearly $110,000 in today’s dollars. His boss agreed, but Comptroller General Lindsay C. Warren did not. Hevenor took the government to court and lost—a final indignity for the man on Wake with the longest streak of bad luck. He died in 1971 at the age of 84. —Joseph Connor

This story was originally published in the December 2017 issue of World War II. Subscribe here.