In 1944, though their country lay shattered after years of Axis occupation, Greek partisan forces engaged in a bitter civil war with far-reaching consequences.

On a Friday in mid-September 1944, after a fierce three-day battle outside the Greek town of Meligalas, the victors marched 50 captive soldiers and more than 1,000 civilians into the main square. There, with the frenzied assistance of other villagers, they proceeded to torture, mutilate and murder them—some victims shot or stabbed, others hanged, many beaten to death with clubs, stones, canes, even shoes. When the slaughter was over, the killers unceremoniously dumped the corpses into a nearby well.

The perpetrators were not soldiers of the occupying German, Italian or Bulgarian armies; they and their victims were Greek. The incident occurred during an unspeakably bitter civil conflict between the communist and nationalist forces of a war-ravaged Greece, a clash that began even while the country remained under Axis control.

On Oct. 28, 1940, Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini sent his forces into Greece. The Greek army, despite having no armored support, mounted a ferocious counterattack and drove the Italians back across the Albanian border in what many historians consider the first Allied land victory of World War II. Shortly thereafter the British reinforced the Greek army with a small expeditionary force. In April 1941, however—outraged by the humiliating repulse of his Italian allies and anxious to keep the British from using Greece as a base from which to bomb critical oil fields in German-allied Romania—Adolf Hitler postponed his plan to invade Russia and instead launched a blitzkrieg toward Athens. By early June the Wehrmacht had overrun mainland Greece and the Aegean Islands, driving out Allied forces and sending King George II and his government into exile. What followed was a brutal occupation that lasted nearly three and a half years.

Hitler carved up the country, keeping the most strategically important locations (including Athens, Thessaloniki and several key islands) for himself and doling out the remainder to Italy and Bulgaria (which promptly annexed a long-contested portion of northern Greece). The German high command then established a Greek puppet government comprised of collaborators who considered it preferable to go along with their conquerors rather than die resisting them.

It soon became evident, however, no workable accommodation was possible. From the outset the Germans imposed restitution fees, ostensibly to reimburse them for the cost of their invasion and occupation. After stripping the country of its currency, they systematically seized crops and other foodstuffs, as well as the products of Greek commerce, and diverted all commodities and modes of transportation for their own use. The program, little more than officially sanctioned pillaging, left the conquered without food or adequate clothing. By the winter of 1941–42, during what has come to be known as the Great Famine, Greeks were starving by the hundreds each day, with the death toll climbing exponentially. The collaborationist government, which didn’t want to displease its German masters, did nothing to help. To make matters worse, when other nations sent food for relief, it often fell into the hands of either the Germans or government officials and black marketers, who would swap it in exchange for money or personal property. Literally adding insult to injury, as the Greeks starved, growing numbers of German soldiers and civilians came to tour the nation’s ancient monuments, bask on its beaches and frolic in the clear Aegean.

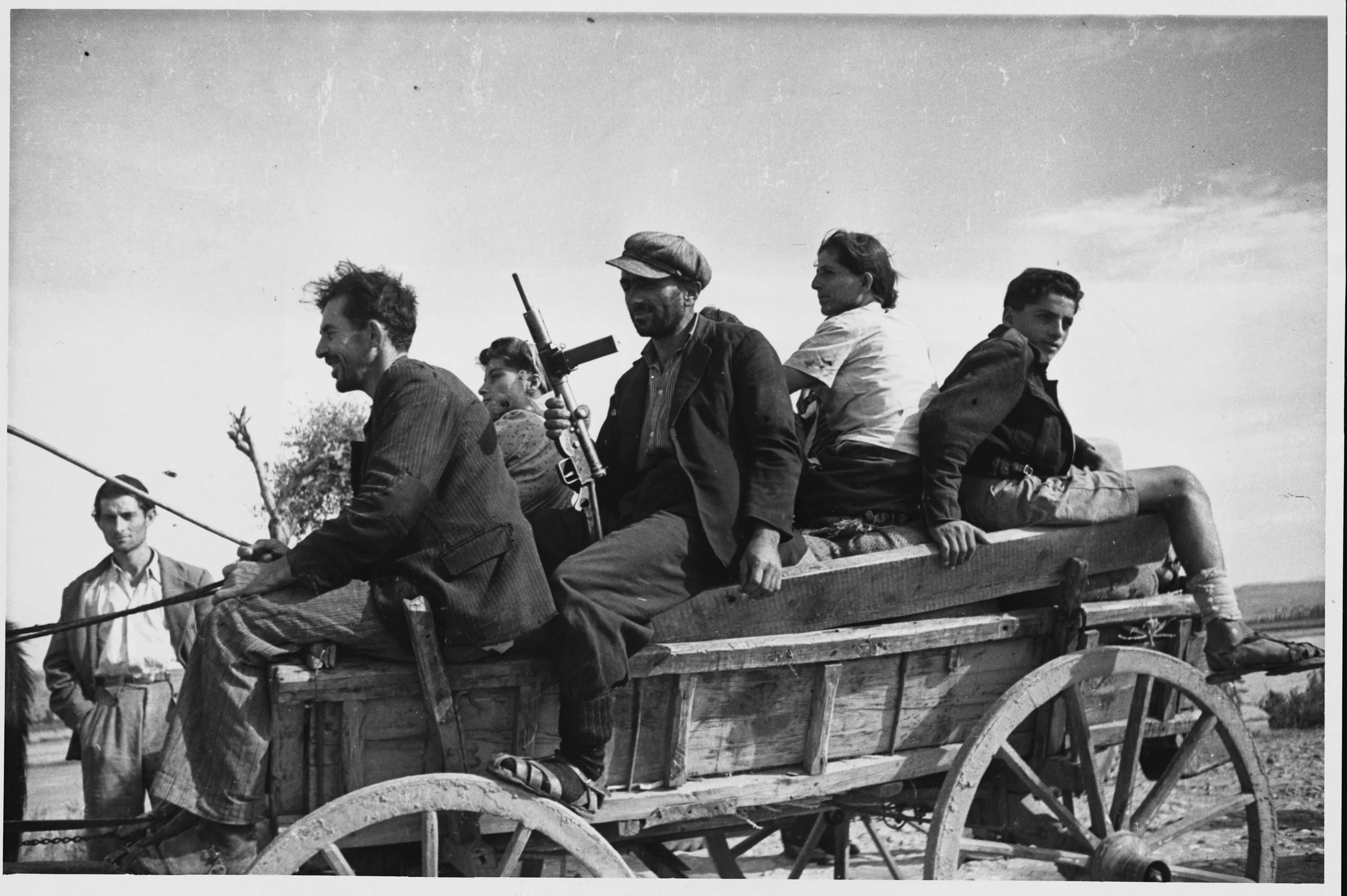

The heavy hand of the occupiers drove thousands of Greek men and women into the mountains to form resistance units. In addition to striking at Axis patrols and outposts, they attacked German supply lines, seriously impeding the flow of materiel to Hitler’s forces in Africa. Far from united under one banner, however, the resistance groups were separated by politics and even regional mistrust. There were really only two forces of significant size—and their mutual enmity nearly rivaled their hatred of the Germans. The largest and best organized movement—the National Liberation Front (EAM) and its military arm, the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS)—had been formed in 1941 by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and was in direct ideological conflict with the smaller, weaker National Republican Greek League (EDES).

The two forces would occasionally unite to fight their common enemy. The most dramatic example of their tentative cooperation was a raid designated Operation Harling. On Nov. 25, 1942, 86 ELAS and 52 EDES partisans—supporting a dozen-man demolition party of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE)—destroyed the Gorgopotamos railway viaduct linking Athens and Thessaloniki, temporarily crippling a vital supply link to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s forces in North Africa. Although Operation Harling proved one of the most successful Greek tactical operations of the war and provided a textbook example of effective guerrilla warfare, the truce between EAM and EDES was an uneasy one at best.

Reprisals by the Germans were harsh and indiscriminate, and their Italian and Bulgarian allies followed suit. It was not uncommon for them to execute 50 or more captives, mostly noncombatants, for every Axis soldier killed by Greek guerrillas. They destroyed hundreds of villages—often after having killed the entire male population—and left nearly 1 million people homeless. Again, the collaborationist government did nothing to protect its people. Instead, in a show of solidarity with Germany it formed a 22,000-strong all-Greek force known as the Security Battalions, which roamed the countryside killing anyone suspected of fighting as, or sympathizing with, partisans. The battalions took special pains to hunt down communists, who had opposed the prewar Greek monarchy.

The Germans and their allies initiated an anti-Semitic mini-Holocaust in Greece, rounding up as many of the nation’s Jews as possible—generally with the assistance of the collaborationist government—and shipping them off to Auschwitz and Treblinka. More than 80 percent of Greece’s estimated prewar Jewish population of 60,000 died during the occupation, though some escaped extermination by fleeing to the hills and joining the resistance.

According to the Greek National Council for Reparations From Germany, when the Germans finally evacuated in October 1944 they left more than 800,000 Greek corpses in their wake. As Hitler’s forces withdrew, they destroyed whole towns and villages, roads, bridges, canals and power stations, leaving widespread devastation. Yet the two major Greek resistance forces—EAM and EDES—did not wait for the Germans to leave before turning on one another. They embarked on a civil war that would continue long after the Axis guns were stilled and would suck in British and American dollars, military resources and troops.

In early 1944, months before the German exodus, the communist-dominated EAM set up a provisional government in the mountains of northern Greece, openly defying both the EDES forces and the royalist government in exile. Immediately after the Germans left, the British, who had actively supported Greece throughout the war, re-established a presence in Athens. They brought the opposing factions together and set up a fragile unity government. That effort soon came apart when ELAS refused to turn in its weapons and disband. On Dec. 3, 1944, civil strife broke out, and for the next month and into the New Year, in a series of clashes known as the Dekemvrianá (“December Events”), Athens became a battleground between ELAS and the British-supported government forces.

Ironically, amid the partisan chaos, many of those who had collaborated with the Germans during the occupation managed to elude arrest and punishment, some even finding positions within the government. Greek authorities did try several collaborationist leaders, sentencing one to death (later commuted to life), two to life imprisonment and others to various prison terms. One of those receiving a life sentence was former Prime Minister Ioannis Rallis, who was instrumental in creating the Security Battalions. However, Greek authorities showed little interest in pursuing German war criminals, which was a source of embarrassment to the British, who had set themselves up as the power behind the new government. This pattern, tactfully described as benign judicial neglect, is hardly surprising when one considers that in 1945 liberal-leaning Prime Minister Nikolaos Plastiras was driven from office when it was discovered that during the war he had offered to head a pro-German government in Athens. Two years later the former head of EDES had to resign his cabinet position when his wartime ties to German officers came to light.

The Dekemvrianá was the start of the partisan clash. Filling the vacuum left by the German withdrawal, ELAS had established control of most of Greece, with the exception of Athens and Thessaloniki. Britain—under the direction of Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his foreign secretary, Anthony Eden—refused to allow communist rule in Greece and committed troops and weapons to the defense of the government. Seeking to minimize popular support for EAM, the British rounded up 15,000 suspected communist sympathizers, deporting 8,000 to camps in the Middle East.

ELAS responded in brutal fashion by unleashing a “Red Terror,” seizing and executing thousands of members of what it deemed “reactionary” families and even whole villages. They abducted thousands more “enemies of the people”— generally citizens guilty of nothing more than a modicum of prosperity—driving them through gauntlets of leftist-allied countrymen on into the wintry hills without shoes or coats and feeding them little or nothing. Many died of exposure, while those who couldn’t keep up were shot.

While ELAS exacted its bloody reprisals, the government continued its policy of communist suppression, marked by forced evacuations and mass deportations. Tragically, it was noncombatant civilians who suffered most.

Inevitably, EAM-ELAS was destined to lose, given its enemy’s superior numbers and technology. By early January 1945 ELAS forces—battered by British artillery, armor and air attacks—had conceded defeat. Peace was formalized on February 12 with the signing of Treaty of Varkiza, which promised a political voice to the members of EAM-ELAS, provided they surrender their weapons. Most leftists complied and turned in their arms, only to expose themselves to an unchecked rightist backlash. By July, during the ensuing “White Terror,” a British-supported national guard largely comprising former troops of the collaborationist Security Battalions had arrested some 20,000 EAM-ELAS members and executed 500. By comparison, the total number of collaborationists executed by the postwar Greek government was 20. By year’s end ELAS resistance fighters in Greek prisons outnumbered jailed collaborationists 10-to-1. Some would languish behind bars well into the 1960s.

Greece held a general election in March 1946, but in protest of the unfolding rightist persecution the Communist Party of Greece refused to participate, virtually ensuring the victory of its nationalist opponents. And within months a plebiscite voted to return King George II to his throne. With the formal return of the royalists to power, civil war broke out in earnest. By early 1947 the collective force of communist guerrillas—rebranded the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE)—controlled much of the countryside, and by year’s end it had again established a provisional government in the northern mountains.

Neighboring Yugoslavia and Albania initially supported the DSE, and its fighters crossed freely back and forth across their borders. One of its more contentious programs involved the abduction of Greek children between 3 and 14 years of age— as many as 30,000, according to some sources—to be raised in Eastern Bloc countries as communists. (Greece’s Queen Frederica responded by setting up a network of refugee camps to shelter such at-risk children.) In July 1948, however, relations between Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and Yugoslavia’s Marshal Josip Broz Tito suffered a major rift that resulted in the two countries severing ties. The Greek communists had to choose a side; they aligned with the Soviets, whereupon Tito closed his border with Greece. Although this proved a major blow, by that time the DSE faced an even starker reality —the United States had actively taken the royalist side.

Since its intervention in 1944 Britain had been supporting nationalist forces with economic and military assistance, but by February 1947 Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s government—deep in the throes of postwar austerity—informed the United States it was unable to continue its support and asked President Harry Truman to assume the role of Greece’s protector. Truman saw an immediate opportunity to take a stand against an increasingly powerful Soviet Union, while announcing to the world America’s intention to stem the communist tide wherever it arose. As Truman saw it, communism threatened both Greece and Turkey, and he feared that the resultant “collapse of free institutions and loss of independence would be disastrous not only for them but for the world.” On March 12 he addressed a joint session of Congress to petition for extensive and ongoing aid for both countries.

After detailing the devastation wrought by the Germans, Truman blamed “a militant minority, exploiting human want and misery, [that] was able to create political chaos.” Greece, he said, was “threatened by the terrorist activities of several thousand armed men, led by communists, who defy the government’s authority” and rely upon “terror and oppression, a controlled press and radio, fixed elections and the suppression of personal freedoms.” Only with support from the United States could Greece realize its destiny as a “self-supporting and self-respecting democracy.” Describing a potential communist takeover as having effects that “will be far reaching to the West as well as to the East,” Truman said, “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.”

By redefining the very nature of American foreign policy, Truman was in essence declaring the Cold War. He pointed to the Soviet Union as the main foe of democracy; the communist credo, he argued, presented a global threat to freedom, through both military invasion and, more diabolically, internal subversion.

Ironically, the basis for Truman’s argument that the Soviets were behind the Greek communist insurgency was flawed. The Soviet Union had, in fact, provided virtually no help to Greek communist forces. At the Fourth Moscow Conference in October 1944 Churchill and Stalin had entered into a coldblooded secret pact—the “percentages agreement”—whereby the Soviets ceded 90 percent control of Greece to Great Britain in exchange for 90 percent Soviet control over Romania, and 75 percent influence over Bulgaria. Thus when the Greek Civil War heated up, the Soviets were content to watch from the sidelines. As one ELAS veteran recalled years later, “Right until the very end…we did not receive a single Soviet bullet.”

Nonetheless, Truman successfully painted the Soviet Union as the chief threat to global democracy, and Congress accepted his not-unreasonable premise. Truman requested an allocation of $400 million—what he referred to as “an investment in world freedom and world peace”—for the provision of economic and military aid to Greece and Turkey; two months later Congress complied, thereby initiating the Truman Doctrine. It would define American foreign policy, for better or worse, for decades to come.

The Greek civil war raged until the fall of 1949, inflicting further destruction on a country that had yet to emerge from the devastation of World War II. The Greek National Army, fortified by American dollars, weapons and advisers, systematically drove the leftists from their mountain strongholds. The last battle—fought on Mounts Grammos and Vitsi in far northern Greece—saw the communist fighters hopelessly outgunned and outnumbered more than 5-to-1. Finally, on Oct. 16, 1949, the Greek communist radio station announced an end to hostilities “to prevent the complete annihilation of Greece.” As the firing ceased, many of the communist fighters fled across the border into Albania. An estimated 150,000 Greeks had perished since the commencement of civil hostilities, including 165 priests slain by the communists. Up to a million people had been displaced from their homes. But for the first time in nearly a decade, peace prevailed.

In the wake of the conflict Greek authorities outlawed communism. Although there were sporadic guerrilla flare-ups over the next few years, the KKE’s struggle soon dissolved into a war of words, marked by dissension and splits within the party.

Far from embracing the “guarantees of individual liberty” and “freedom from political oppression” for which Truman had so eloquently campaigned, the new Greek government instituted a rightist regime defined for the next several years by repression and intolerance. It came as no surprise; a precedent had been set before the outbreak of World War II, when in 1936 Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas—with the full awareness and support of King George II—had established a neo-fascist dictatorship that banned political parties, abolished parliament, arrested dissenters and introduced systematic police brutality. When the Germans forced that government into exile in 1941, many Greeks hoped it would never return.

Yet the post–civil war Greek government—installed with the economic and military support of the United States and run by nationalist politicians, backed by the army and marked by autocratic suppression of political expression—was little better than the Metaxas dictatorship. Shortly after a 1967 military coup that brought anti-communist Greek army officers to power, the junta designated thousands of its leftist opponents “enemies of the country”—even as it provided state pensions for former members of the Security Battalions. Not until the 1974 collapse of this “Regime of the Colonels” did Greece emerge from the miasma of military occupation and internal strife to reassert its claim as the cradle of democracy.

Ron Soodalter has written for Smithsonian, Civil War Times, America’s Civil War and Wild West. For further reading he recommends Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–1944, by Mark Mazower; The Struggle for Greece, 1941–1949, by C.M. Woodhouse; and Children of the Greek Civil War: Refugees and the Politics of Memory, by Loring M. Danforth and Riki Van Boeschoten.

Originally published in the March 2015 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.