Recommended for you

THROUGHOUT NAZI GERMANY, the exploits of U-boat commanders and their crewmen were glorified during the early years of the Battle of the Atlantic. U-boatmen were hailed as heroes; U-boat commanders became legendary figures draped with Iron Crosses. And the successes of this “Happy Time”—as the Germans called the period from January to July 1942, when U-boats obliterated Allied shipping along the U.S. East Coast—propelled the desire of future U-boat commanders to attain the same high level of achievement. U-352’s commander, Hellmut Rathke, was no exception.

By all accounts, though, U-352 was essentially a failure. U-352 did not sink any ships. U-352 did not account for any Allied tonnage loss. None of U-352’s torpedoes hit their intended targets. U-352 gained no notoriety—except for being the first U-boat the U.S. Coast Guard sank in World War II after Rathke ordered a brazen attack in broad daylight.

Despite the latest in U-boat design and marine engineering, and despite all the technological advances made to the predators of the deep, avarice and errant human decision-making in this case ultimately proved to be the more destructive weapon.

underwater threat

THE EVOLUTION of World War II U-boat design was rooted in the successes of earlier models from the Great War, when Germans had perfected methods of submarine warfare that were a substantial threat to Great Britain. Now Nazi Germany required a boat with a more effective range to reach American shores. Nazi Germany needed an efficient and proficient killing machine. Enter the Type VII U-boat.

Prior to 1940, a Type VII U-boat variant first launched in 1938—the Type VIIB—ruled the sea. This latest in U-boat design and engineering was a marvel: the introduction of a second rudder gave it an improved turning radius and a repositioned aft torpedo tube allowed it to carry a greater number of torpedoes. Those attributes, when combined with an extended range, increased speed, and more expeditious dive time, made for a formidable variant—one vastly superior to previous U-boat designs.

The improvements kept coming. The advent of a form of active sonar—the Sondergerät Für Active Schallortung or S-Gerät—allowed for the detection of both ships and mines. But its installation required 24 inches of space not available in the Type VIIB. As a result, a new German U-boat was introduced in 1940: the Type VIIC.

In an engineered environment where every square inch of space has purpose, fractions of inches matter. In order to create the space the S-Gerät required, German engineers had to design and fabricate a new hull section, install additional framing, enlarge the conning tower, lengthen the fuel tanks, lengthen the saddle tanks, and install a new filter system throughout the U-boat. Quite an engineering undertaking for an additional—albeit necessary—two feet of space.

The Type VIIC went on to become the most produced U-boat throughout the war and the workhorse of the U-boat fleet. Type VIICs unleashed vicious attacks in the North Atlantic and ravaged Allied shipping. The significance of this effort should not be underestimated. In January 1942, when U-boats first arrived along the American shores, a British Admiralty Report succinctly declared: “Although we shall not win the war by defeating U-boats, we shall assuredly lose the war if we do not defeat them.” Both sides knew the stakes. Success in the North Atlantic—by cutting off war supplies to Britain from the West and thereby putting a stranglehold on the British—meant Germany had a chance to win the war. The loss of thousands of Allied sailors and soldiers, the destruction of hundreds of thousands of tonnage, and significant damage to the American psyche were largely the work of the Type VIIC silent hunter-killers.

Type VIIC U-boats were constructed at 15 shipyards throughout Germany. Flensburg, Germany’s largest northernmost city, with a seafaring history dating back to the 1500s, was home to the fabled shipbuilder Flensburger Schiffbau-Gesellschaft (FSG). It was here that 28 U-boats were built for the Kriegsmarine, including 20 Type VIICs. Situated close to the Danish border at the extreme west of the Flensburg Fjord, the shipbuilder had easy access to the Baltic Sea. U-352, the second Type VIIC U-boat FSG constructed, was launched on May 7, 1941.

U-352’s new crew had been ordered to Flensburg that month, prior to launching, and lived on the U-boat while final construction and outfitting were completed. The additional 24 inches of length notwithstanding, accommodations aboard U-352 were cramped: a complement of 46 crewmen—three officers, one midshipman, 18 petty officers, and 24 seamen—would make U-352 home.

harsh but loyal nazi commander

CHOSEN TO LEAD U-352’s new crew was 31-year-old Kapitanleutnant Hellmut Rathke, a Flensburg resident. Rathke was an interesting choice as commander since he had only six years of naval experience—none of which was below the surface and none of which involved submarines. Clearly, the graduate of the naval class of 1930 was not chosen for his submarine acumen—but he may have been chosen because he was a strict disciplinarian. His methods were effective. The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) later reported that Rathke “inflicted a martinet’s discipline” on his men. Such measures may have been seen as necessary, as 13 of U-352’s crew members were younger than 21, which ONI characterized as “extreme youth.”

On top of that, Rathke was an ardent Nazi. A declassified ONI document noted that “[Rathke] professes unqualified admiration for Hitler and National Socialism.” He considered Hitler knowledgeable in all aspects of life, calling the Führer “a genius in everything,” not just military matters, and a leader who “unified all the German peoples in Europe.”

During the final stages of construction, Rathke was often seen at the Flensburg shipyard in a wheelchair; he had been injured in a skiing accident sometime before taking command of the U-boat. Still, Rathke had the respect of his men—or, at a minimum, instilled fear in them. He even punished one of his sailors for getting drunk while on leave by canceling the remaining leave and detaining him onboard U-352. When construction was complete, U-352 headed to the U-boat base at Kiel, Germany, for five weeks of sea trials, culminating in the boat’s commissioning on August 28, 1941. Afterward it made stops in Danzig and Flensburg for tactical sorties and minor repairs, then returned to Kiel for provisions that included 14 torpedoes and thousands of rounds of ammunition for the 88mm deck gun and 20mm antiaircraft gun. U-352 was ready for war.

itching for action

ON JANUARY 15, 1942, U-352 departed Kiel. The mission for the U-boat’s first patrol was simple, if not broad: disrupt Allied shipping off the southern coast of Iceland, where British, American, and Canadian troops held a presence to deter a German invasion. Icelandic waters were important for troop transport and the ferrying of military goods and fuel. Rathke and his men were excited to do their part for the Fatherland by continuing the destruction of Allied vessels by those in the U-boat force who had come before.

Rathke had higher aspirations still. Heinz Karl Richter, a fireman aboard U-352 who served under Rathke, said in a postwar interview that Rathke was “obsessed with receiving a Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross.” It was the epitome of Germany’s Iron Cross awards and, along with its several variants, the highest award in Germany—issued to U-boat commanders for sinking 100,000 tons of enemy ships.

But their first three weeks at sea passed with no action. The crew must have had a severe case of langweiligkeit—boredom—when a merchant vessel finally appeared on the horizon. A spark of energy pulsed through the U-boat as the men aboard raced to their battle stations. U-352’s moment had arrived. Just as the crew prepared to fire on the unsuspecting vessel, however, four British escort corvettes—small warships—appeared. U-352 had been spotted, and was forced to abandon the attack and immediately descend.

The British convoy escorts dropped depth charges and, according to intelligence reports, a crewman aboard U-352 remembered “some very respectable explosions.” None, however, caused any damage. U-352 slunk away into the darkness and lived to fight another day.

For the next two weeks, the U-boat patrolled Icelandic waters without sighting another vessel. Low on fuel and full of torpedoes, it started a return course to the U-boat base at Saint-Nazaire, France. While en route, the submarine spotted a distant enemy destroyer. Rathke fired a fan of four torpedoes. All four missed.

Yet, despite a failed first war patrol, three sailors aboard U-352 were awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class—Rathke included—when they reached their new home port on February 26, 1942. It is not known specifically why Rathke or his men—likely the two other officers—were recipients. The award was given out relatively freely, even more so as the war progressed. It may have been intended as a motivator, rather than in recognition of a job well done. And in the case of U-352, there would have been good reason to motivate the crew.

Nazi Germany was asking the 46 men aboard U-352 to go back to sea after an unsuccessful mission. This time, U-352 was going to go much farther than Iceland: U-352 was going to go to America’s shore. If Rathke had felt the pressure to earn an Iron Cross prior to the first war cruise, now that he had essentially been given one, the pressure surely mounted to prove he deserved it. After an engine overhaul in St. Nazaire, U-352 was ready for its second war patrol.

The U-boat departed the pens at St. Nazaire on April 7, 1942, for the three-week trek across the Atlantic. It was ordered to patrol off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in waters referred to as the Diamond Shoals. These rich hunting grounds had already been dubbed “Torpedo Alley” by the Allied forces. Surely a U-boat captain could find a kill in these bountiful waters.

On the long cruise to Carolina, the men were permitted to sunbathe on deck. The tight, cramped quarters of nearly 50 men was stifling; any intake of fresh air was welcome. According to ONI documents, the U-352 crew enjoyed meals composed of “meat, potatoes, canned vegetables, and fruit.” A supply of gin was stored onboard as well.

U-352 arrived at Diamond Shoals on May 2, 1942. There, the Americans provided U-352 with a not-so-warm welcome. The men aboard had been listening to American jazz radio programs when the U-boat had to crash dive to avoid bombing by a twin- engine aircraft flying coastal surveillance. Three days later, a U.S. Army Air Forces plane spotted U-352 and dropped two bombs. Although the pilot claimed a kill, U-352 escaped with no damage. However, U-352’s luck was about to run out.

Between the bombings and crash dives to avoid the coastal convoy protections now in place in American waters, U-352 spotted numerous Allied vessels. In the days immediately after arriving near the American shore, the U-boat fired eight torpedoes at various Allied vessels. All eight missed.

reckless daylight attack

ON MAY 8, 1942, at 9 a.m., the U.S. Coast Guard Thetis-class cutter Icarus was ordered from Staten Island, New York, to Key West, Florida, to escort ships along the Eastern Sea Frontier—the U.S. Navy operational command that extended from Canada to Florida. Originally built as a Prohibition enforcement vessel for chasing rumrunners, Icarus was well suited for its new duties protecting Allied ships in coastal convoys. Armament aboard Icarus included depth-charge racks, .30- and .50-caliber machine guns, and a large, three-inch deck gun.

By the next day, Icarus was transiting off North Carolina. The trip so far had proven uneventful besides the regularly scheduled zig-zag pattern steering movements. With the captain retired to his quarters, there was no sign that Icarus would soon make history. The cutter was cruising at 14 knots. According to U.S. Coast Guard records: “The sea was calm. There was a slight swell. Visibility was about 9 miles.”

At about 4:25 p.m., Icarus’s sonar operator reported a “rather mushy” contact off the port bow. Although it was an indefinite contact, he made the wise choice to track it nonetheless, and Icarus’s executive officer summoned its commanding officer, Lieutenant Maurice D. Jester, to the bridge.

At about the same time, aboard U-352, Rathke sighted the silhouette of a lonely ship on the horizon some 1,900 yards away. Rathke must have been desperate for a win. He looked through the attack periscope, quickly ordered everyone to battle stations, and fired a single torpedo. But he did not fire on an unsuspecting cargo ship; he fired on a fully armed U.S. Coast Guard vessel while in shallow water, which limited the U-boat’s ability to hide—in broad daylight. The torpedo exploded 200 yards off Icarus’s port quarter. And the hunter quickly became the hunted.

In a deadly game of cat-and-mouse, Rathke—thinking he was in even shallower water than he actually was and, thus, in a still more desperate position—ordered U-352 to hide in Icarus’s wake to mask the U-boat’s propeller noise. But the men aboard Icarus proved the more proficient hunters. Icarus dropped five depth charges. Aboard the U-boat, a radioman shouted: “Achtung! Wasserbomben!” U-352 shook violently as Icarus unleashed hell from above. U-352’s executive officer was killed. Its attack periscope was destroyed. Gauges exploded. Crockery shattered. The men inside were tossed around like dolls.

Icarus dropped three more depth charges. Large air bubbles rose to the surface; U-352’s propulsion and electrical systems were destroyed. The U-boat was crippled—literally dead in the water.

Rathke, who knew his U-boat was damaged so severely that escape in it was impossible, ordered the crew to don lifejackets and breathing apparatuses. He then ordered the saddle tanks on the side of the vessel to be filled with air so the submarine could rise, and gave the order to abandon ship.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Like a whale breaching the surface, U-352 suddenly appeared from the deep. Rathke shouted for all men to leave the U-boat. As the men poured into the sea, Icarus’s three-inch deck gun blanketed the conning tower and perforated the steel hull with piercing rounds, and its machine guns came to life, also raking the conning tower. The continuous fire was so intense that the U-boatmen did not utilize any of U-352’s weapons.

The U-boat remained on the surface for five minutes before descending into the blue abyss. Fireman Heinz Karl Richter insisted it was Rathke’s obsession with getting a Knight’s Cross that “led to recklessness, ultimately resulting in the U-boat’s sinking.”

Icarus circled the spot and, for good measure, dropped an additional depth charge to ensure the U-boat would not hunt again. Thirty-three men from U-352 had made it out before the sinking, but 13 sailors went down with it. The men who escaped, Rathke among them, swam away from the stricken sub as quickly as they could. As they floated on the surface like flotsam awaiting their fate, the commander shouted out one last order—telling them not to give the Americans any information of military value. The situation was especially dire for four wounded men, including Machinist Mate Gerd Reussel, whose leg had been severed by gunfire from the Icarus. While in the water, Rathke removed his own belt and made an impromptu tourniquet around Reussel’s stump.

Icarus was ordered to pick up all survivors and transport them to the naval shipyard at Charleston, South Carolina. The wounded men were brought aboard first; Reussel died four hours later, and the U.S. Coast Guard went on to treat him with dignity, burying him with full military honors at Beaufort National Cemetery in South Carolina, some 70 miles farther south.

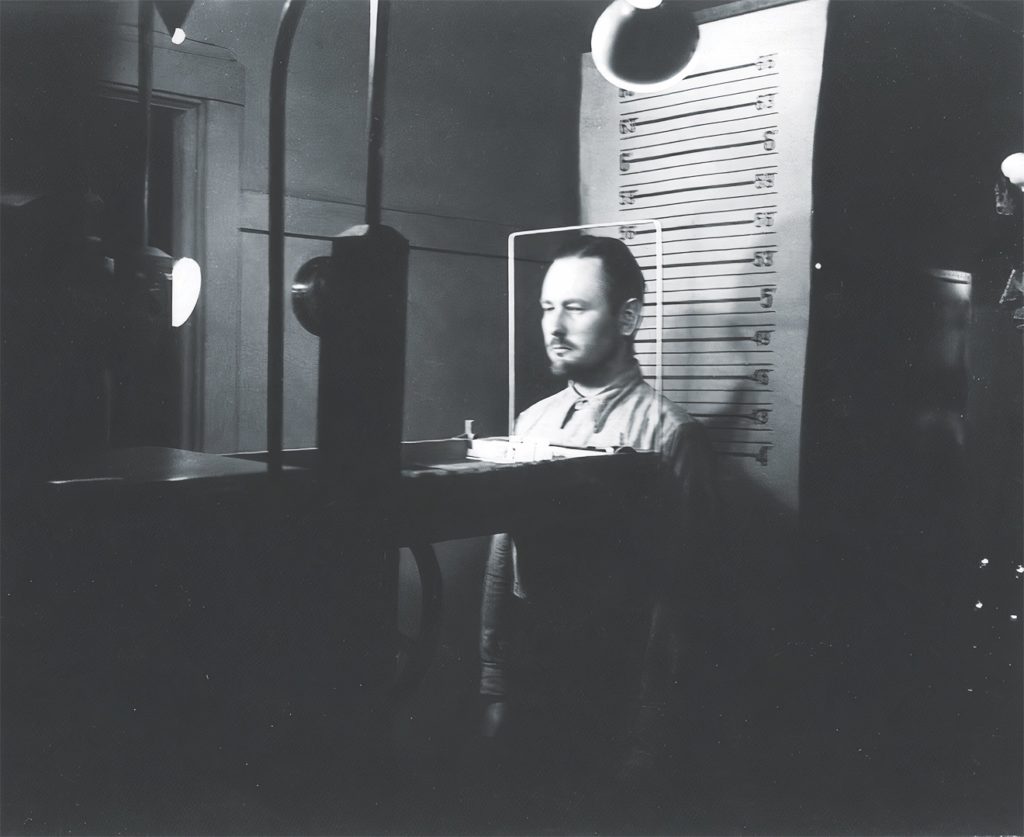

Icarus slides into the port at Charleston, South Carolina, with a distinctive cargo: the survivors of the sunken U-352. Below: two U.S. Navy officers and a British officer question Rathke (in shorts) and an executive officer in Charleston’s navy yard. There’s no misreading Rathke’s expression. (National Archives)

Now prisoners of war, the men of U-352 were photographed, fingerprinted, and interrogated. But the Coast Guard did not separate Rathke from his men once aboard Icarus, as would have been the norm—most likely because all this was a first for them: their first sunken U-boat of the war and first time taking prisoners. That allowed Rathke to be, according to a later U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence report, “twice able to lecture his men.” He repeated the orders he gave while in the water—not to divulge any information to the Americans. And he made it abundantly clear it would be disrespectful to their fallen brethren if anyone spoke to their interrogators.

Rathke may not have been tactically sound, but he was security conscious. And it paid off: a report issued by the U.S. Atlantic Fleet Anti-Submarine Warfare Unit dated May 18, 1942, explicitly stated: “the captives were allowed to mingle with each other to the extent that the U-boat captain warned and instructed his crew on matters concerning security. This undoubtedly vitiated to a large extent efforts to obtain information which might otherwise have been of extreme value.”

After the POWs were transferred to a detention camp at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, a special interrogation unit composed of American and British officers had their turn with the men. But, again, they divulged no information of significance. Rathke himself reported very little. Staying true to his belief in Nazi principles, Rathke, an intelligence report noted, “refused to believe that Germans inflicted outrages upon Poland and Poles.”

The survivors from U-352 would now sit out the rest of the war on land, Rathke included. They were transferred to multiple camps throughout the United States before reaching their permanent POW camp in Papago Park, Arizona, which held an abundance of U-boat prisoners.

There, Rathke maintained his iron fist and rigid discipline over his men. According to ONI reporting, he disciplined seamen for mundane things such as failure “to police lavatory” and listening to a “distant conversation at officers table.” Even the cook caught the wrath of Rathke, and was confined to his quarters for three days for allowing “bread leavings to be thrown into the drain.” At the end of the war, Rathke returned to Flensburg; he lived there until his death in 2001.

from feared warship to tourist sight

U-352 TODAY REMAINS at the bottom of the Atlantic at a depth of 110 feet, and is one of the most popular sport dives along the U.S. East Coast. I have dived the sunken submarine multiple times over the past two decades, and it’s always a haunting sight. As I descend into history through the blue water, wearing more than 100 pounds of dive gear, the hazy outline of the conning tower—listing sharply to starboard—comes into view from about 40 feet above the wreck. U-352 is remarkably intact for having sustained multiple depth charges, with most of its deterioration due to nearly 80 years spent in salt water. Pockets of the U-boat’s outer skin have withered away, exposing skeletal remains of the steel ribs and frames that strengthened the pressure hull— the circular watertight compartment in which submariners live and work. Having peered through several of the U-boat’s open hatches, I can attest to the claustrophobia and confines of the steel coffin in which, due to Rathke’s fatal error, 13 men are forever entombed. ✯

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.