Soon-to-be centenarian John G. (“Brad”) Bradley Jr. grew up in Hartford, Connecticut, where his dad patented a welding technique for assembling Royal Typewriter Company portable typewriters. During World II, as John Sr. redirected his expertise to weld steel frames for U.S. Army troop transport gliders, Brad became a U.S. Navy aviator. On May 5, 1945, just three days shy of V-E day, Bradley was piloting his Grumman Avenger torpedo-bomber on a training mission off the coast of Rhode Island when he spotted—and promptly reported—a German U-boat. Brad is still haunted by what followed.

What was growing up in Hartford like? Were you an athlete?

As a freshman at Bulk High [Morgan Gardner Bulkeley High School], I broke the school record in the mile in my second meet. They nicknamed me “Legs Bradley.”

When and how did you join the Navy?

In 1942. I was trying to become a V-5 Aviation Cadet. A sailor gave me the exam at the post office in Hartford. Those were pretty tough questions, but he said, “You passed everything fine.” I waited, that was the summer of ’42. And then I received orders to go to 120 Broadway, the Equitable Life Building in New York City. And sitting behind the desk was a naval officer. He was from a family we knew. And he said, “How’s your mom and dad, your brother?” I about fell over. He told me, “We want you mentally and physically fit, but we have to have a good character as well. I don’t have to ask you much about your character.”

Is that when you were sworn in?

December 12, 1942. I learned later that future president George [H.W.] Bush was sworn in the 12th of December 1942 on Lower Broadway. There were only a dozen of us that day, so he must have been there. He and I were sworn in together, and I didn’t realize it.

When did you first get a chance to fly?

After I went through pre-flight. In Texas I learned to fly the Taylorcraft, a little single-engine plane; instead of a stick to fly it, it was a wheel. Next I had to go to the naval air station north of Memphis. That’s when I flew the biplane [the N3N, nicknamed the “Yellow Peril” because of its paint scheme and its use by student pilots]. Oh, I love that plane. Flying came easy to me. I got my wings in October ’44. They sent me [next] to Pensacola to get checked out in the Texan, the SNJ.

Then you qualified to fly the Avenger torpedo-bomber in Fort Lauderdale.

A very forgiving airplane.

What was the next destination?

Norfolk, Virginia, assigned to a composite training squadron, VC-15. In May 1945, the Avenger component, maybe four or five TBFs, went up to the Naval Air Station in Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

Your plane had a regular crew.

Yeah, a radioman and a gunner. My radioman was from Philadelphia. The gunner was a boy from Atlanta. He was a nut, had tattoos on his chest. A tattoo over one nipple said “sour.” And the other one had a tattoo saying “sweet.”

But you didn’t fly with either of them on May 5.

One night after reaching Quonset we went to Providence. One of the guys knew the night watchman at a brewery there. He said: “Listen, if we promise not to make noise, the watchman will let us have free ale.” Clifford Brinson [another pilot’s radioman] didn’t drink, and I didn’t drink. At 3:30 in the morning, we finally took a cab back to Quonset Point. And when it came time for assignments, we were the only two not hungover. So, Brinson wound up as my crewman. Just he and I took off from Quonset.

What was your mission?

We were going to be a “target” for submarines out of Groton, Connecticut. To train their lookouts to spot aircraft. But the weather was spotty. Scuddy, low clouds and patchy fog. So, our submarine blinkered: returning to port. We made a wide turn south of Westerly, Rhode Island, heading to Block Island. And Brinson said, “Mr. Bradley, I can’t believe there’s a submarine on the surface, just east of Montauk Point [Long Island].” It was about 10:15 a.m. when we spotted it. There was a navigation buoy southwest of Block Island. I estimated him doing about 10 knots heading for that buoy. But what were we gonna do? And I said, “Let’s hope he doesn’t see us. We don’t have anything but fuel in our tank. Let’s get back to Quonset.”

What happened after you landed?

We went immediately to the base administration building. And there was a lieutenant commander who debriefed us in a separate room outside the base admiral’s office. He must have asked us the same questions over and over for about three hours. He kept running back and forth, back and forth to the admiral’s office. “You sure? You sure?” And we said, “We know what we saw from what they taught us in the recognition courses.” Recognition of not just the enemy ships, but all foreign ships and planes.

It was foggy by the time they finished debriefing and we were excused. Since my hometown was Hartford, I drove back there and spent the night at my home.

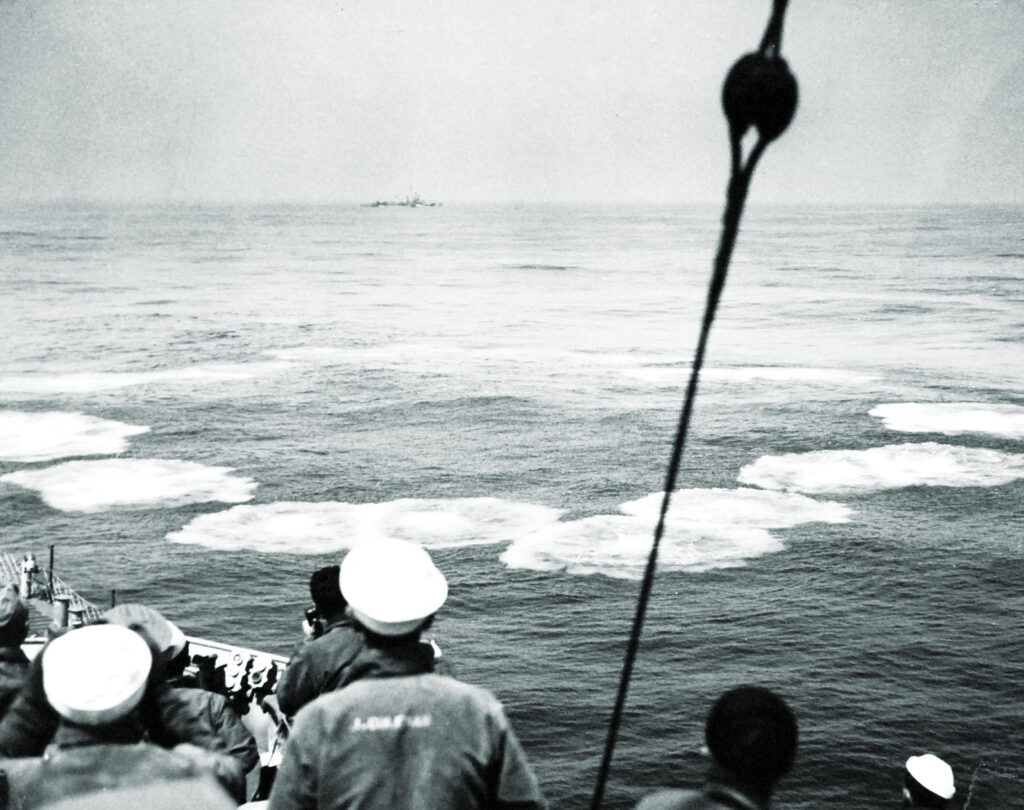

Subsequent events indicate that the German U-boat you and Brinson spotted was U-853. About seven hours later, U-853 torpedoed and sank Black Point,a coal freighter, north of Block Island—the last U.S. merchant vessel sunk by a German U-boat. When did you first learn of it?

That evening. I loved going dancing, so I went to the Knights of Columbus in downtown Hartford. And during intermission of the dance, I went outside. The Hartford Times newspaper building was right next door. And the newsboys were running out the front door with their newspapers. “Extra, extra, German submarine sinks coal vessel. 12 lives were lost.” I remember standing there and I shook my head. At first I said to myself, “Oh my God, there goes my Air Medal.” Then I realized, “This isn’t funny. 12 lives were lost.”

Hours after Black Point sank, U-853 was cornered and sunk by U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ships. The sighting you made could possibly have changed history. After you returned to Quonset from Hartford, was there any feedback or follow-up on what you’d reported?

No, I was a youngster, 21 years old. And you’re always taking orders and you’re not much in command of anything. My God, if I were more senior or more mature, I would’ve really gone on after that.