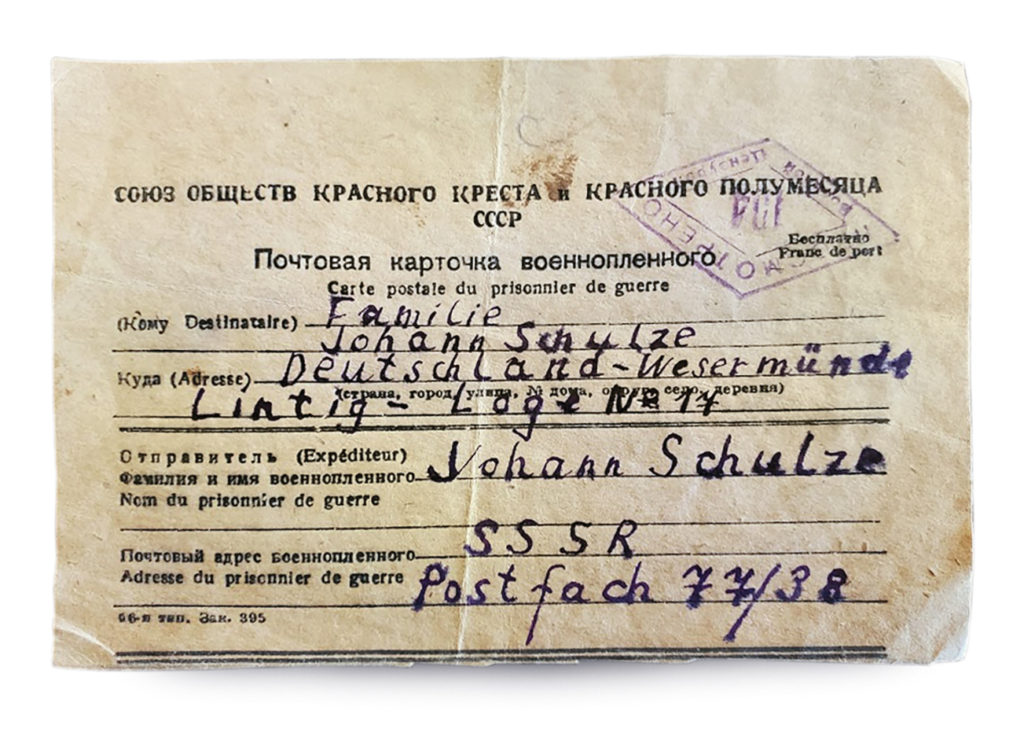

Q: My German grandmother gave me this document. Her two younger brothers served in the Wehrmacht. The older brother was killed fighting in Yugoslavia; the younger brother, Johann, was captured on the Russian Front.

The family didn’t know what had happened to him until they received this postcard, dated Aug. 14, 1947; he returned to Germany several years later.

I’ve always wondered: Was it a common practice for the USSR to allow prisoners to write home?

—Michael O’Donnell, Huntington Station, N.Y.

A: Your great-uncle Johann Schulze was one of nearly 2.4 million Germans the Soviet Union captured during the war. Research by historian Mark Edele, a specialist in Soviet history, has found that 356,687 of them died in captivity. Tens of thousands of others remain unaccounted for, the causes of death unknown. The harsh climate and postwar deprivations made life difficult for the prisoners — as did vengeance for the boundless destruction and devastation the Nazis had caused. At the war’s end, many in German uniform did all they could to surrender to the forces of the Western Allies, not wanting to be captured by the Soviets.

Yet Soviet prisoners of the Germans fared even worse, with an estimated 43 to 63 percent perishing while captive — many murdered alongside civilians in concentration and death camps. In the years following the war, the Soviet Union used German POWs as forced laborers; the last prisoner was released from captivity in 1955 following petitions by West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

It’s difficult to know for certain how many German prisoners were able to complete a note like Johann’s. Research into the Soviets’ treatment of German POWs has been complicated by closed archives and an ongoing politicization of the issue; Edele states that “sources are a problem.”

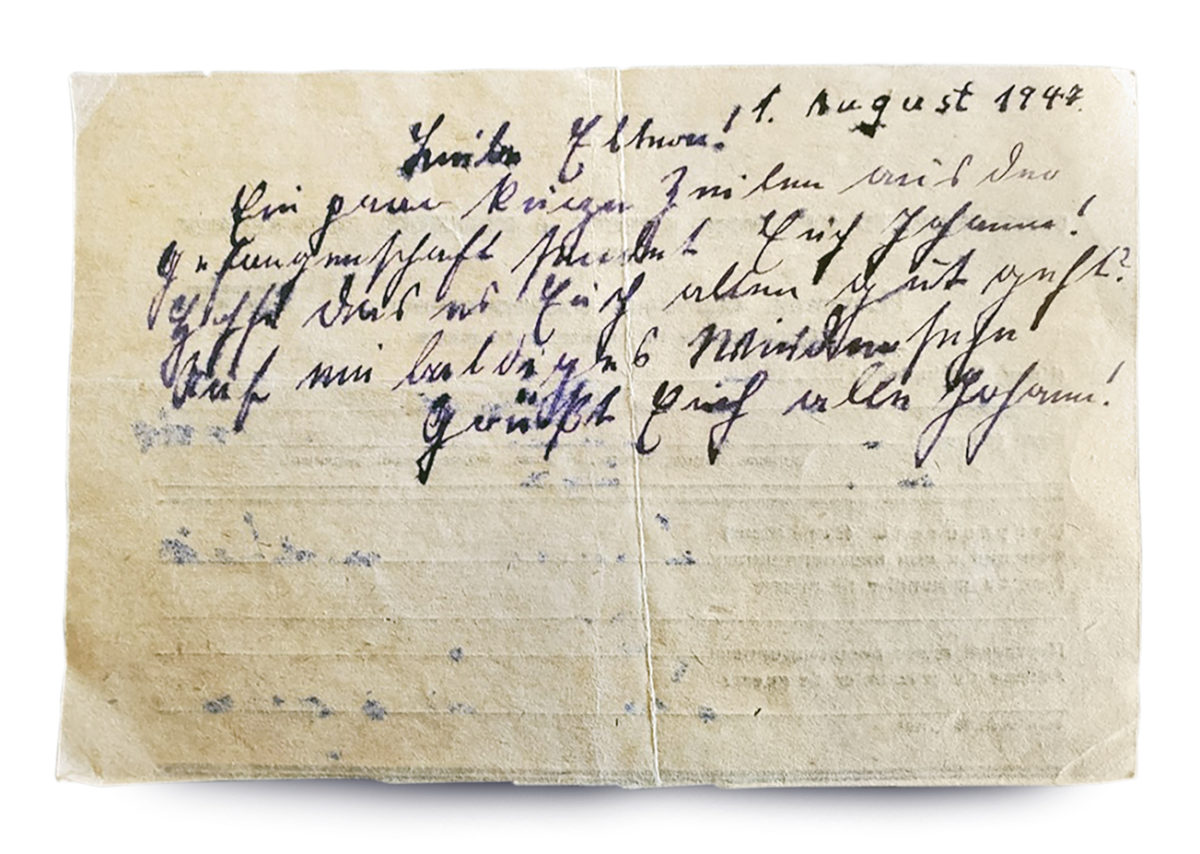

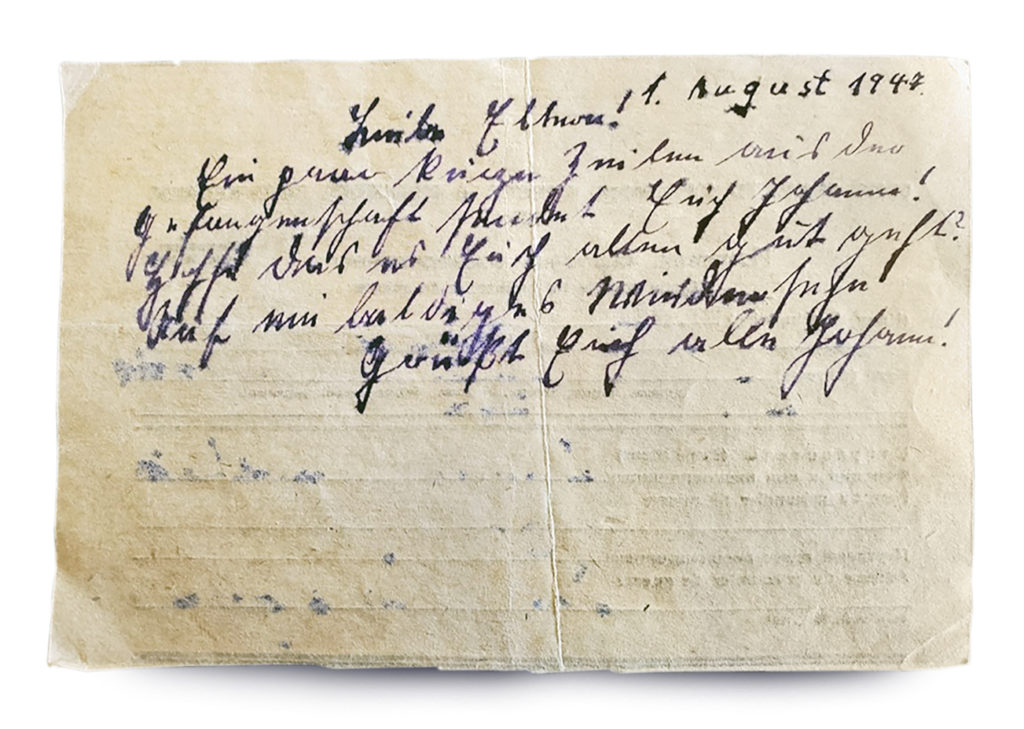

The United States held roughly as many German POWs as the Soviets — under much different circumstances. The National WWII Museum’s archive contains letters from Germans held in Louisiana as well as in the American Zone of Occupation in Germany. As it did with your uncle, the International Red Cross facilitated this contact with the outside world. The letters home bear messages strikingly similar to that of Johann, who wrote: “Dear parents, your Johann sends you a couple of short sentences from prison. Hoping that all is going well for you all? I hope to see you again soon. With greetings to you all, Johann.”

Comparatively, Johann was spared the worst. He was one of the lucky ones, returning to grow old with his family.

— Kim Guise, Senior Curator and Director for Curatorial Affairs

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Have a World War II artifact you can’t identify?

Write to Footlocker@historynet.com with the following:

— Your connection to the object and what you know about it.

— The object’s dimensions, in inches.

— Several high-resolution digital photos taken close up and from varying angles.

— Pictures should be in color, and at least 300 dpi.

Unfortunately, we can’t respond to every query, nor can we appraise value.