The tropical heat in Darwin, Australia, was brutal on the afternoon of July 12, 1942, when four pilots of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 49th Fighter Group clambered into Curtiss P-40E fighters for what was supposed to be just one more training mission. They were First Lieutenant I.B. ‘Jack Donalson and Second Lieutenants John Sauber, Richard Taylor and George Preddy Jr.

The mission started out in routine fashion, with Preddy and Taylor peeling off to play the role of Japanese bombers on which Sauber and Donalson would practice their interceptor skills via a dummy attack. Sauber made the first pass, but as he dived on Preddy’s plane, he became disoriented, possibly blinded by the sun, and misjudged his distance. Too late he tried to pull up, but slammed into the tail of Preddy’s aircraft at 12,000 feet, sending both planes tumbling earthward in flames.

Sauber, who never made it out of his cockpit, was killed. Preddy managed to bail out but came down in a tall gum tree that shredded his parachute and dropped him through the branches to the hard ground below. Aided by Lieutenant Clay Tice, who spotted his position from his P-40, ground crewmen Lucien Hubbard and Bill Irving found Preddy, who had a broken leg and deeply gashed shoulder and hip. After the squadron’s surgeon examined Preddy in the airfield’s infirmary, he announced the young airman would have bled to death if he had not been found before morning.

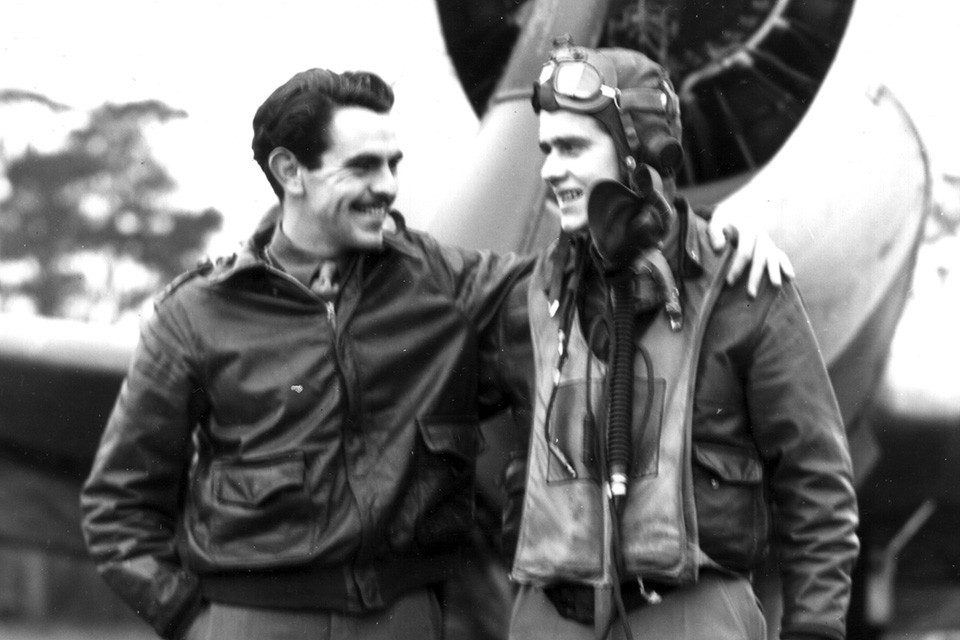

George Preddy’s bloody baptism into World War II had come at the hands of his own comrades. But he would recover from that initial mishap and be reassigned to another front, where his dogfighting skills made him the war’s top-scoring North American P-51 Mustang ace at age 25.

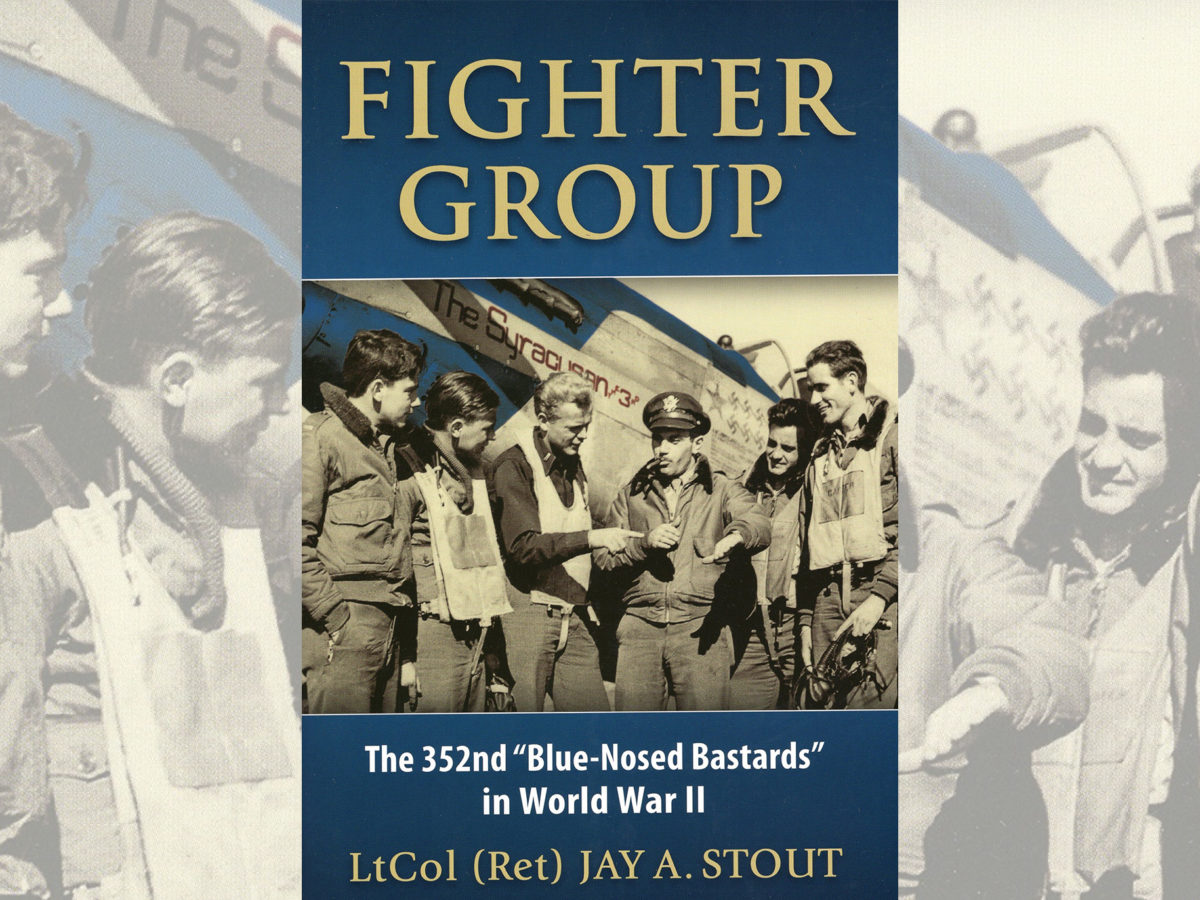

When the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 352nd Fighter Group arrived at Scotland’s Firth of Clyde on July 5, 1943, its pilots were mostly grass-green rookies fresh from flight school. On that same day, however, Queen Elizabeth delivered a few seasoned campaigners to bolster the new unit. One of them was Preddy.

Learning to fly the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt meant Preddy had to do some retraining before he was battle-ready, but after a year out of action he was chafing for combat. The budding hero was addicted to crap games, and when he tossed the dice he would yell “Cripes a’ Mighty!” for good luck. To enhance his chances aloft, he had those words painted on the nose of every warplane he ever flew.

Operating from Bodney Airfield, the 352nd got into the action on September 9, 1943, flying cover for out-of-ammunition and low-on-fuel Thunderbolts of the 56th and 353rd Fighter groups as they returned from escort missions. It was boring at first, but these newcomers would soon be in the midst of massive air battles over the Third Reich.

Recommended for you

On what became known as Black Thursday, October 14, 1943, Preddy was among 196 frustrated escort pilots whose almost empty fuel tanks forced them to turn for home just as the Luftwaffe swept down onto Eighth Air Force bomber formations attacking the Schweinfurt ball-bearing works. The resulting carnage among the unguarded bombers made it clear the P-47’s 200-gallon-per-hour fuel consumption handicapped its value as an escort fighter.

Short range notwithstanding, Preddy and Cripes A’ Mighty stayed busy sticking as close and long as possible to the Strategic Bombing Offensive’s four-engine formations throughout the autumn of 1943. On December 1, he and a formation of Thunderbolts rendezvoused with bombers returning from an attack on Solingen. He latched onto the tail of a Messerschmitt Me-109 approaching the last bomber box from the rear. When the German saw the charging P-47, he made the mistake of trying to out dive Preddy’s 13,000-pound gun platform. At 400 yards Preddy opened fire and held down the firing button as he closed to 100 yards, disintegrating the luckless interceptor. Preddy’s 487th Fighter Squadron was the only one in the 352nd Group to score kills on that day of light fighter opposition.

On December 22, the 352nd lifted off to guard part of a returning force of 574 bombers that had savaged the marshaling yards of Münster and Onabrück. Preddy’s wingman that day was brilliant young concert pianist Lieutenant Richard L. Grow. Just east of the Zuider Zee, the pair of Americans became separated from the rest of their flight during a swirling, confused dogfight in blinding cumulus clouds. Climbing back to the bombers’ altitude, they spotted a gaggle of six Messerschmitt Me-210s and 10 Me-109s chewing on the tail of a crippled Consolidated B-24 Liberator. Unhesitatingly diving into the interceptors, Preddy quickly torched the Me-210 nearest the bomber before the Me-109s could interfere. With the pack now chasing them, the intrepid Thunderbolt pilots plunged for the clouds. Preddy managed to outpace his pursuers, but the fighters on Grow’s tail apparently finished him before he could reach the fleecy cloud cover. The blossoming concert star never made it back to Bodney, but the limping Liberator, Lizzie, got home. Preddy was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross for that action, but instead received his country’s third-highest award for heroism, the Silver Star.

January’s weather was both sides’ worst enemy. On January 29, 1944, the ice storms abated long enough for 800 bombers to fly against the industrial district of Frankfurt. The 487th was part of the fighter presence dispatched to meet the bombers on their return leg. Preddy quickly shot down a Focke Wulf Fw-190 over the French coast, but then flew over a flak pit and was hit hard. He coaxed his smoking Thunderbolt up to 5,000 feet, but could not make it across the English Channel. When his dying warbird dropped below 2,000 feet, he bailed out and inflated his pressurized dinghy while his wingman, 1st Lt. William Whisner, circled overhead until air-sea rescue units could triangulate a radio fix on the downed airman. A Royal Air Force flying boat landed, but in the rough seas it ran over Preddy and nearly caused him to drown. Then the rescue plane broke a pontoon while trying to take off, and had to call for additional assistance. By the time a Royal Navy launch arrived to tow the crippled flying boat to port, however, the American airman had been given a quart of brandy by the British crew and was beginning to thaw out.

Soon after Preddy’s Channel swim, the 352nd began to switch from the P-47 to North American’s new P-51 Mustang fighter. On the morning of April 22, 1944, the 487th Squadron took off to shepherd bombers on a drawn-out mission to Hamm, Sost, Bonn and Koblenz. In between bombing runs, the Mustangs swooped down onto the airfield at Stade. Preddy and two comrades simultaneously opened fire on and pulverized a Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine bomber that had just taken off, resulting in each of the Americans receiving a .33 kill credit.

On April 30, Preddy shot down an Fw-190 in a one-on-one dogfight 17,000 feet above Clermont, France. From that point, now-Major Preddy’s score would rise at a steady rate as he and his new airplane became better acquainted. Between April 30 and the Normandy landings on June 6, Preddy torched 4 1/2 enemy aircraft. He completed a standard 200-hour tour of duty and two 50-hour extensions, and was starting a third. He expressed little outward interest in his score, preferring instead to concentrate on how much nearer the war’s end was drawing and what he could do to hasten it. As the pivotal summer 1944 battles on the Western Front churned below him, Preddy shot down nine more Germans from June 12 to August 5.

He downed an Me-109 on August 5, and when he returned to Bodney he heard the weatherman’s prediction of bad flying conditions for the next day, along with word that no flights would be scheduled. That same night the 352nd gave its war bond drive party, and the combat-weary Preddy enjoyed himself greatly at the bash. Following that celebration, he reeled off to his quarters past midnight. Twenty minutes later an aide shook him awake to inform him a mission was scheduled after all, and it was his turn to serve as flight leader. After a farcical briefing during which he was so drunk he fell off the podium, Preddy’s buddies sat him in a chair and held an oxygen mask over his nose until he appeared somewhat sober. They kept a close watch on their swaying major until takeoff, and continued to observe him as he led them aloft on a maximum-effort mission to Berlin.

The weather was beautiful, with mostly clear skies. The Luftwaffe was up in force. Before the Americans reached their target, more than 30 Me-109s intercepted the group of Boeing B-17s Preddy’s unit was shepherding, arriving from the south. Preddy led an attack from astern and opened fire on a trailing plane, apparently killing the pilot. That Messerschmitt instantly heeled over and spiraled down in flames. Wading into the formation, Preddy came up behind a second Me-109 and ignited it with a flurry of hits to the port wing root. The pilot bailed out. Advancing into the enemy formation from the rear, the Americans picked off one fighter after another. Meanwhile those in front took no evasive action, seemingly unaware of the destruction creeping up from behind.

Preddy torched two more 109s before the remaining Germans perceived the trailing menace and went into a dive. The Mustangs followed hungrily. Preddy dispatched his fifth victim as the dwindling flock of Germans descended to 5,000 feet and one jerked his plane into a sharp left turn. This pilot had evidently seen Preddy and was trying to get onto his tail, but the American snap-rolled to the left and passed over his opponent. The German gamely tried to copy the maneuver and opened fire, but the angle was wrong for him. With the speed Preddy had built up in his roll, he was able to drop astern of his foe and fire from close range. That airman, too, bailed out.

After landing at Bodney, 1st Lt. George Arnold photographed a wan, sick-looking Preddy climbing from his out-of-ammunition Mustang. Gun camera footage and testimony from fellow pilots confirmed his achievement of six kills in one flight. War correspondents and photographers were on the way, and for the next few days Preddy was the most exalted soldier in Europe. Lieutenant Colonel John C. Meyer recommended his 25-year-old hero for the Medal of Honor for his exploits of August 6. To Meyer’s surprise and anger, however, on August 12 Brig. Gen. Edward H. Anderson instead pinned the Distinguished Flying Cross on Preddy’s tunic.

Counting ground victories and partial kills, Preddy’s score now stood at 31, and another of his combat extensions had expired. It was time for him to go home on leave. He would never again fly Cripes A’ Mighty 3rd — senior officers who incorrectly assumed the major was going home for keeps assigned it to another pilot. But as Preddy told his minister back in Greensboro, N.C., Reverend, I must go back. There was no way George Preddy was going to leave any job unfinished.

After almost two months at home Preddy managed to acquire a fourth tour extension, returning to England and taking command of the 352nd’s 328th Fighter Squadron. He was given a brand-new P-51D-15NA. The 328th’s victory tally trailed that of the other 352nd squadrons, and Preddy was expected to boost the pilots’ confidence and morale. He did as much as he had time to do.

Following an uneventful mission on October 30, Preddy led his fliers on November 2 to escort bombers to Merseburg, Germany. Spotting more than 50 suspicious contrails at 33,000 feet, he set out to cut off the enemy’s approach to the bombers, guiding his pack to the Me-109 formation’s rear. Although he had never before used his plane’s new British-designed K-14 gunsight, he fought as though he’d been using it for years, sending an Me-109 down in flames.

On November 21, Preddy destroyed an Fw-190 just before the overtaxed Luftwaffe virtually disappeared for an entire month. Daily, Preddy and his men scanned empty skies. Meanwhile, however, the Germans were building up their store of fighter aircraft in preparation for the looming Ardennes offensive. When 600,000 previously undetected Wehrmacht troops surged through the freezing, fog-draped Ardennes Forest on December 16, they were protected from aerial attack by the worst weather the Allies had seen since the invasion. For a full week the 352nd was grounded by cotton-thick overcast. When the 328th Squadron’s pilots brazenly lifted off on December 23 from their new airfield outside Asch, Belgium, the clouds forced them to fly so low that they had to dodge trees. They found nothing to shoot at, and returned to base to spend another 48 frustrating hours in their freezing forest clearing encampment.

On Christmas Day Preddy and nine of his pilots took off for a hopeful sweep over confused woodland fighting. After patrolling for three fruitless hours, they received radar vectoring to intercept bandits just southwest of Koblenz. Diving on the targets, Preddy quickly flamed two Me-109s, forcing their pilots to hit the silk. The dogfight carried the combatants close to Liege, where Preddy latched onto the tail of an Fw-190. At less than 100 feet he was pouring bullets into his victim when an American anti-aircraft emplacement opened fire on both planes with .50-caliber machine guns. Realizing he was shooting at a friendly plane, the gunner stopped after firing only about 60 rounds, but it was too late. One of the big bullets had hit Preddy, and although he managed to release his canopy, he was unable to bail out. Mortally wounded, he crash-landed near the flak pit.

Major George Preddy never knew defeat in combat, but at age 25 he fell victim to human error. His status as the top-scoring Mustang ace of the war—with a total of 27 1/2 confirmed aerial kills—crystallized his standing as one of America’s greatest war heroes.

Valor was apparently a family trait. On April 17, 1945, George’s 20-year-old brother William, who had logged two victories in a P-51, was killed by anti-aircraft fire over Pilsen, Czechoslovakia.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2006 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!

Build Preddy’s final “Cripes-A-Mighty” P-51D for your own Mustang collection. Click here!