Japanese soldiers huddled in caves on the island of Saipan. Having survived a 15-hour banzai attack that left more than 4,000 of their fellow soldiers dead, they had retreated underground and were contemplating suicide. Then someone called out in their language. The person explained that U.S. Marines had surrounded them but offered safety, food and water if they surrendered. The Japanese had no idea the enemy offering them life that July 8, 1944, was a lone 18-year-old Mexican-American from East Los Angeles.

Born on March 22, 1926, Guy Gabaldon was the fourth of seven children. From a young age he shined shoes in his neighborhood to help support the family. By age 12 he was spending most nights at the home of his best friends, Japanese-American twins Lyle and Lane Nakano. Widow Sumi Nakano and her five children became the young man’s foster family. Over the next few years Gabaldon attended Japanese language classes with Lyle and Lane, learning to speak it with proficiency.

Their close-knit family life was shattered after the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In February 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 consigned Japanese-Americans to “relocation centers.” Forced to leave home, the Nakanos were sent to a camp in Heart Mountain, Wyo.

Left on his own, 16-year-old Gabaldon sought to enlist but was refused for being underage. Undeterred, he tried to join the Navy on his 17th birthday but was rejected for having a perforated eardrum. Learning the Marine Corps was looking for Japanese interpreters, Gabaldon convinced a recruiter to overlook both his age and ear problem. He hoped to attend formal language training after boot camp, but a broken jaw from an off-base fight scuttled that plan. Following his recovery he was assigned to an 81 mm mortar platoon and shipped to Hawaii.

Determined to be a translator, Gabaldon pestered superiors until they transferred him to the G-2 (Intelligence) Section of Headquarters Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division. He was trained as a scout and observer.

In May 1944 he learned his regiment would be part of the Saipan invasion. More than 30,000 Japanese soldiers occupied the island, which was also home to tens of thousands of Japanese civilians. His first night on the island Gabaldon left camp without permission and snuck into enemy territory. Happening across a trio of Japanese soldiers, he ordered them to drop their weapons. One raised his rifle, but Gabaldon fired first. The surviving two surrendered.

Gabaldon’s commander, Capt. John Schwabe, threatened him with a court-martial if he left again. The next night, however, the headstrong private again slipped into enemy territory, returning with 52 prisoners. Schwabe reluctantly granted Gabaldon permission to continue his sorties.

That July 8 Gabaldon relied on a captured Japanese to convey the surrender offer to those hiding in the caves. Their commander accepted, and scores of soldiers and civilians duly turned themselves over to an outnumbered and overwhelmed Gabaldon. To buy time, he ordered the soldiers and civilians to separate, then to further separate the sick and wounded from each group. By the time backup arrived, the lone Marine had collected 800 prisoners. When his unit moved on to Tinian, Gabaldon talked hundreds more Japanese into surrendering. Posted back to Saipan to help track down Japanese holdouts, Gabaldon was seriously wounded amid an ambush and medically evacuated to Hawaii.

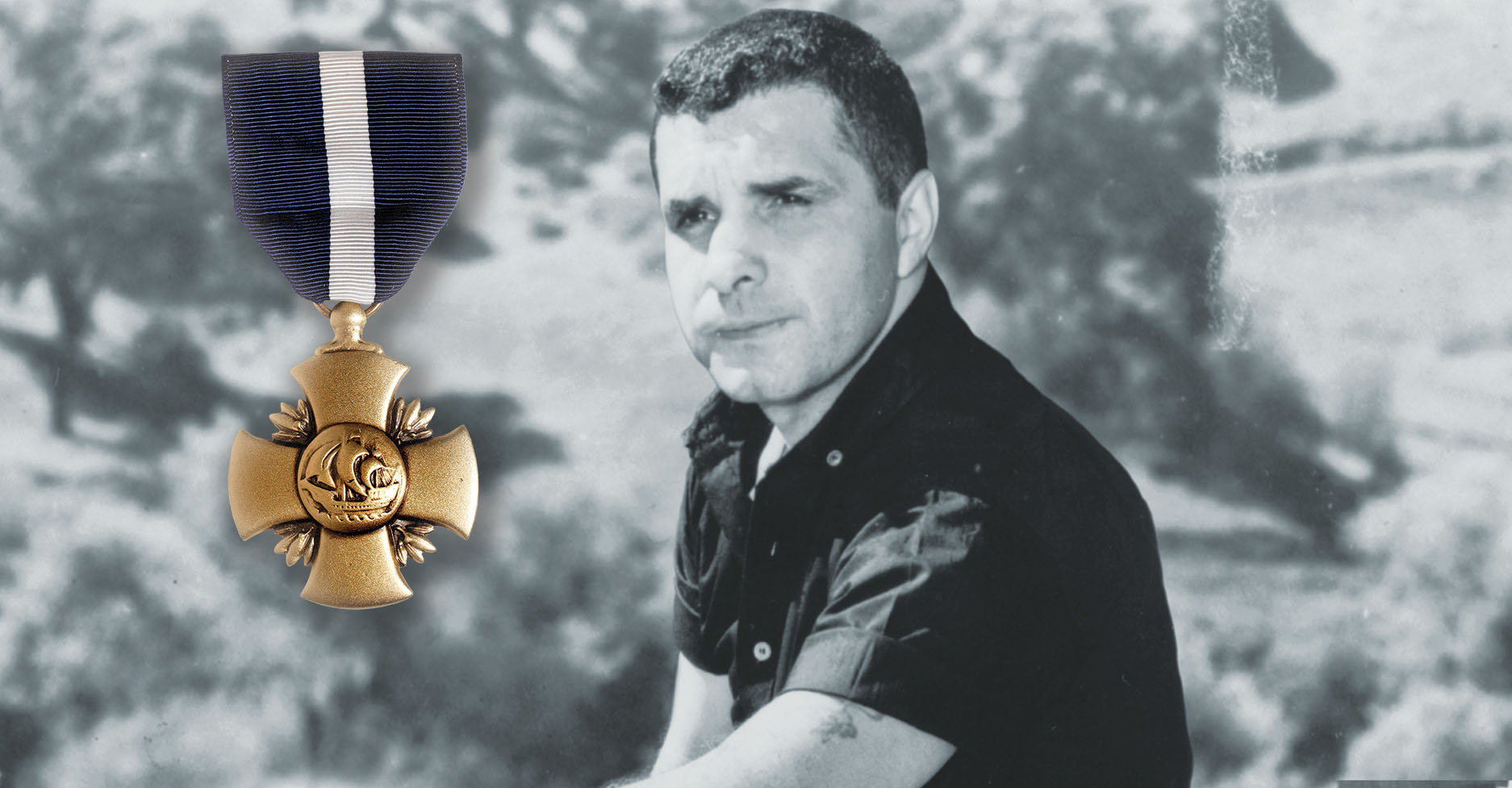

Gabaldon’s efforts on both Saipan and Tinian led to the surrender of some 1,500 enemy troops and civilians, for which he received the Silver Star. Actor Jeffrey Hunter portrayed the heroic Marine in the 1960 film Hell to Eternity. A month after its release Gabaldon’s Silver Star was upgraded to the Navy Cross. The “Pied Piper of Saipan” died on Aug. 31, 2006, at age 80. MH

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook: