Ralph J. Osterhoudt, now 96, was 15 when World War II began. His family’s Hudson Valley, New York, farm was just a bicycle ride north of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Hyde Park estate, where Osterhoudt worked summers. Though a schoolboy, he stepped up to serve, first as a volunteer in the Ground Observer Corps, organized to alert military authorities should enemy aircraft penetrate American skies. Later — as a U.S. Army replacement rushed to Europe’s frontlines — Osterhoudt got a much more intimate view of the war when he fought through France and into Germany.

Describe your life before World War II.

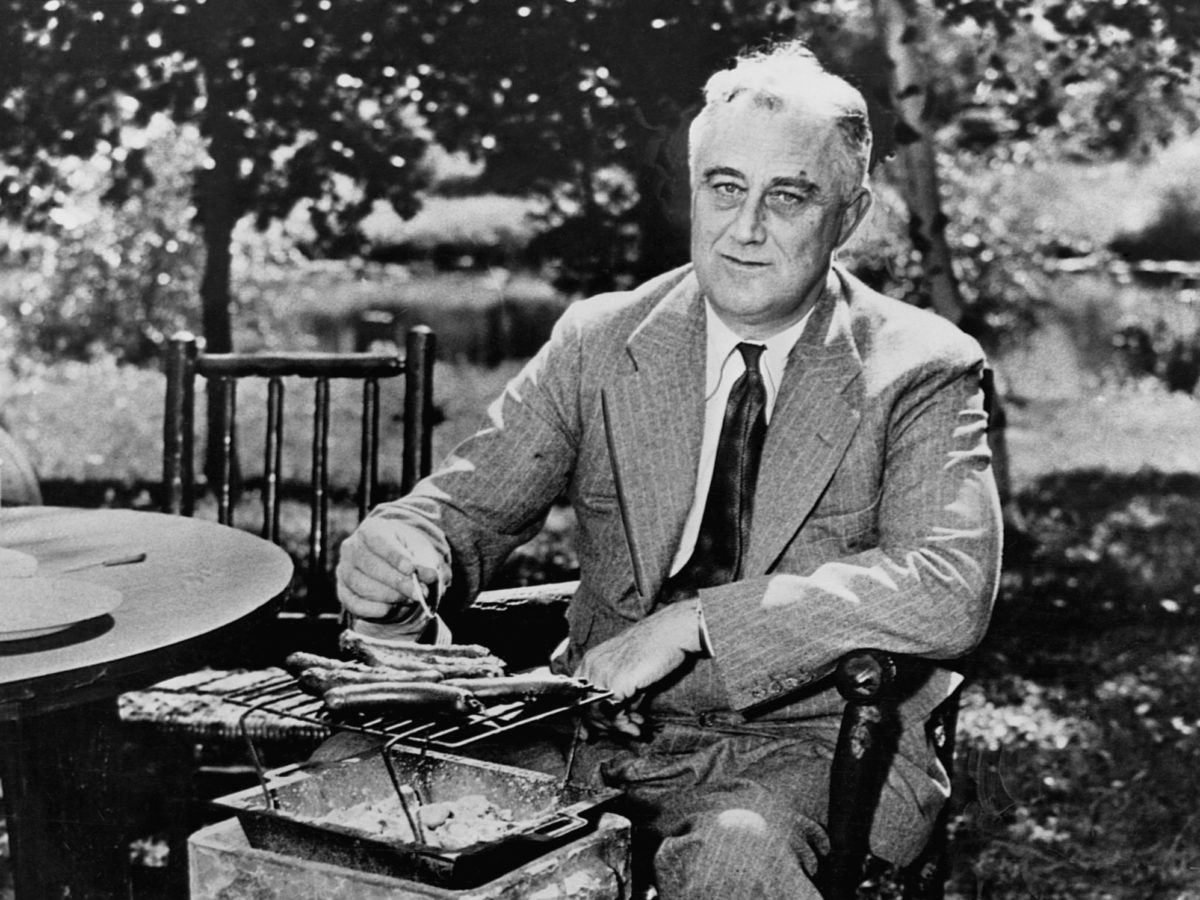

My town of Staatsburg was very small: 500 people. The dirt road we lived on didn’t have electricity or telephone. The first 18 years of my life weren’t anything to brag about. Our 20-acre farm was for our survival. There was very little money. Mostly we bartered. But we ate well — we didn’t eat garbage. My father also worked for Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a gardener. Everybody worked. I had six sisters and five brothers. [Ralph and two sisters survive.] I went to work on our farm at 4:30 a.m. on school days. I milked 10 cows by hand. I’d come home at 3 in the afternoon and milk the cows again.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

You also worked for the Roosevelts.

I used to mow the lawn and plant trees during the summer. One time I was on the mowing tractor when Eleanor came out with a metal pitcher of iced water. She gave me a drink, and we chatted.

In what ways did the war change things?

We were one nation. Everybody was in the war effort. My brother Irving was on the [battleship USS] Missouri for three years. My brother Richard went into the army for six months but was medically discharged. While I was still in high school, I did the ground observer lookout tower.

How did you get involved in that?

The government built this small place overlooking the Hudson River. It wasn’t much bigger than an outhouse, with a roof, a door, and a very small window. Maybe 20 students volunteered to be lookouts. Someone from the government came to the school and told us our responsibilities. You weren’t allowed to have newspapers or bring your homework, because when you’re reading, you’re not watching. Maybe they showed us sketches of what to look for, but we didn’t have to know what enemy aircraft looked like. If something was moving in the air or on the Hudson River, it wasn’t supposed to be there.

More memories of wwii

What did the work require?

Girls with good grades got permission to stand watch in the daytime. The younger boys — high school freshmen and sophomores — went from after school until dark. My hours were from 8 p.m. to midnight, five nights a week.

I lived 4 miles from the observation post. I rode my bicycle there on gravel roads in the rain, snow, whatever. Sometimes it got so cold I wore most of the clothes I had. The post had a telephone, a Coleman lantern, a straight-back chair, a tiny table and a kerosene stove for heat. We didn’t use binoculars. All the nearby homes had blackout curtains, so visibility at night was almost 100%.

When you spotted something all you did was pick up the phone. No dialing or nothing. I forget the name of the unit stationed in Roosevelt’s house [the 240th Military Police Battalion, according to the National Park Service], but someone from the unit picked up the phone. And they said to report and not worry if it’s a false alarm. Thank goodness they were all false alarms.

Did you serve throughout high school?

The Ground Observer Corps was deactivated in May 1944, and on May 29, 1944, I got my induction notice. Two weeks later I would have graduated. They did not let me graduate with my class, but that was okay.

Sounds like you wanted a change.

I could have been deferred — farm work was considered essential — but I didn’t like the farm at all. I went to school every single day and did well. But I used to get on the bus and watch my classmates playing football, baseball, while I had to go home.

Everybody was eager to go. Plus, if you were a male 18 years old and healthy, you couldn’t be seen walking the streets. I went from Fort Dix to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I was in the artillery — 240 mm M1 howitzers. We trained with the 82nd Division, but we were going to Europe as replacements for soldiers killed or wounded.

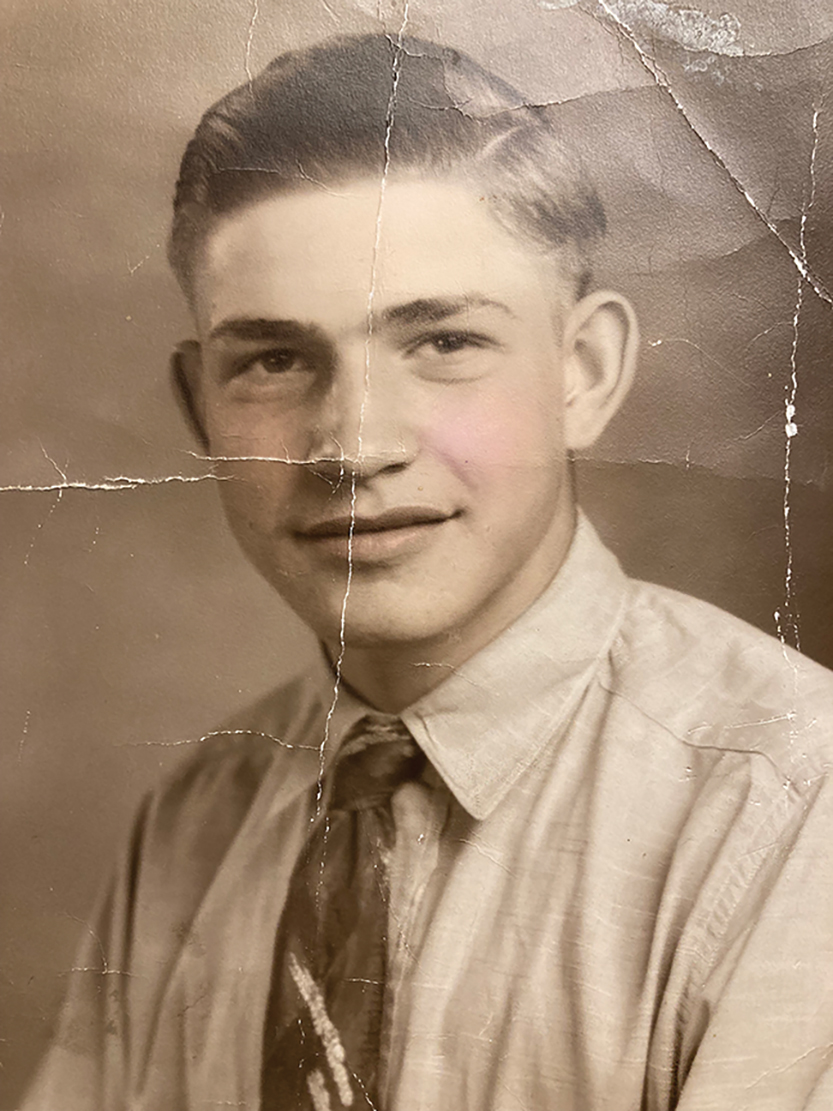

Osterhoudt (at home, more recently) became a soldier before graduating from high school (foreground), arriving in Europe as an artilleryman in early 1945. (Patrick Oehler/Poughkeepsie Journal/USA TODAY NETWORK)

When did you deploy?

Six thousand guys left on the Aquitania [a former British cruise liner] that December. We went across in five days, landed in Glasgow, Scotland, then went by train to Southampton. We boarded amphibious craft, each of us carrying two gigantic duffel bags. It was snowing and cold crossing the Channel. We got dumped out in 2 feet of water on the coast near Le Havre in Normandy on New Year’s Day 1945.

First, we stayed overnight in a brick building with no heat. All of us were freezing wet from the waist down. Finally, somebody located some laundry tubs, filled them with gasoline and lit the fumes for heat. Guys stood around the tubs stripped from the waist down, trying to get their clothes dry. At about 3 o’clock the next morning, we hiked 2 or 3 miles to board a train of cattle cars. The cars had been used for livestock — you can imagine the smell. Someone threw in bales of hay before closing the doors. To keep the snow out, we picked the bales apart and stuffed straw into the big cracks in the floorboards and sides.

We received our orders when we reached a replacement depot just outside Paris. I got assigned to the 575th Field Artillery Battalion down in what was called the Colmar Pocket, in Alsace. Most people have never even heard of it: the French part of the Battle of the Bulge. The French were getting murdered; they didn’t have a piece of artillery.

On January 3, 10 of us got off a train on the outskirts of the Pocket. They took us in at night. The battalion had only been there a couple days before I arrived. They hadn’t even set up the guns. First, I was assigned to headquarters. I was pretty good at typing from high school; I knew Morse code, and I had trained on the German decoding machine at Fort Bragg. The soldier doing those things had been killed, so I got busy with that until I got wounded.

When did that happen?

A couple weeks after I got there. Five of us in a jeep were on reconnaissance, looking for a place to set up a gun. We went down a wooded road. The Germans must have been watching us: they put out a mine. We hit the tripwire when driving back. The blast blew the jeep 20 feet in the air, and when it came down, three of the guys were crushed underneath. The driver and I were thrown clear and survived.

That might have been your ticket home.

I was in a field hospital for two weeks. After that, I went full-time on the guns. I guess I did well because I wasn’t sent back to headquarters. Every two or three days, we moved to a different location, always traveling at night. Half the time you didn’t know where you were.

In February we started to get into mud. We had more trouble in the mud than we did in the snow. We had gigantic tracked vehicles called prime movers that we used for towing heavy artillery. Each gun weighed more than 20 tons. The vehicles were so heavy that when we eventually crossed the Rhine, we went across a pontoon bridge, driving between flags in two feet of water. We didn’t know where the pontoons were.

Once across the Rhine, where did your unit go?

We just went on to German cities like Mannheim, Stuttgart, Munich. Sometimes we were shelling cathedrals and churches — which I’m not proud of — but the Germans were using church towers for observation. War is war.

How long before you finally went home?

I was overseas a year and a half. When the war was over, Gen. George S. Patton wanted a headquarters in Heidelberg, Germany; I was in his headquarters in late 1945 when he got killed. I came back home, exactly to the day, two years from the time I was inducted. I hadn’t realized it, but they were holding a rural letter carrier job for me at the Staatsburg post office. I got home, I think, on a Friday. And Monday morning I went to work at the post office.