“Contagious enthusiasm.” That phrase describes early French aviator Léon Delagrange, who helped spread the gospel of powered heavier-than-air flight through Europe during the first decade of the twentieth century.

Ferdinand Léon Delagrange was born into a well-to-do family on March 13, 1872, in Orléans, France, his father being the owner of a textile factory. Young Delagrange studied art at École des Beaux-Arts and became a respected sculptor before heavier-than-air flying machines grabbed his attention in 1907. Then he totally immersed himself in aviation, joining the Aéro-Club de France and getting elected president. He earned French pilot license number 3. “I believe that the aeroplane is destined to become the bicycle of the airs in tomorrow’s world,” he predicted.

After meeting brothers and aircraft builders Gabriel and Charles Voisin, Delagrange bought a machine from them. Like Delagrange, Gabriel Voisin had been a student of École des Beaux-Arts before turning to aviation. He worked in partnership with Louis Blériot but the two had a falling out and Voisin established his own aircraft manufacturing business with his brother. In addition to making custom-order machines, the brothers designed a pusher biplane powered by a 50-hp Antoinette engine. With a box tail and vertical partitions between the wings, the plane resembled a giant box-kite. A canard provided attitude control and a rudder gave yaw control, both operated by a control wheel that moved fore and aft and side to side. But without ailerons or wing warping the craft lacked roll control, which resulted in uncoordinated, skidding turns. Because of this lack of turn coordination, some question whether it was truly a controllable heavier-than-air machine, which in turn casts doubt on the validity of any records set in it.

Delagrange took his first tentative flight in his machine, the Voisin-Delagrange (the Voisins named their planes after the customers who bought them) on November 5, 1907. After damaging the machine in a hard landing, he ordered another, the Voisin-Delagrange II. He first flew it on January 20, 1908.

In the meantime, another Frenchman, Henri Farman, also bought a Voisin biplane. Being more mechanically inclined than Delagrange, Farman made improvements to his machine that Delagrange soon incorporated on his. The two aviators enjoyed a friendly rivalry as they each set records for distance and endurance. On March 21, 1908, Farman became the first airplane passenger when he went aloft with Delagrange. (The Wright brothers didn’t fly a passenger until May 14. Ernest Archdeacon, a French lawyer and aviation enthusiast, sometimes receives credit as the first airplane passenger in Europe after he flew with Farman on May 29, 1908.)

On March 16, 1908, Delagrange made five flights of 500 to 600 meters (1,640 to 1,969 feet), which made him the first European flier to best the longest flight the Wrights had made (852 feet) on December 17, 1903. On March 20, he flew a circle of about 700 meters (2,297 feet). On April 10, Delagrange flew 2,500 meters (8,202 feet) though his wheels did touch the ground once. The following day, he flew an official distance of 3,925 meters (12,877 feet) thus beating Farman’s distance of 2004.8 meters (6,577 feet). Delagrange’s flight unofficially was 5,575 meters (18,291 feet) but since his wheels touched the ground at the 3,925-meter mark he was not credited with the entire distance.

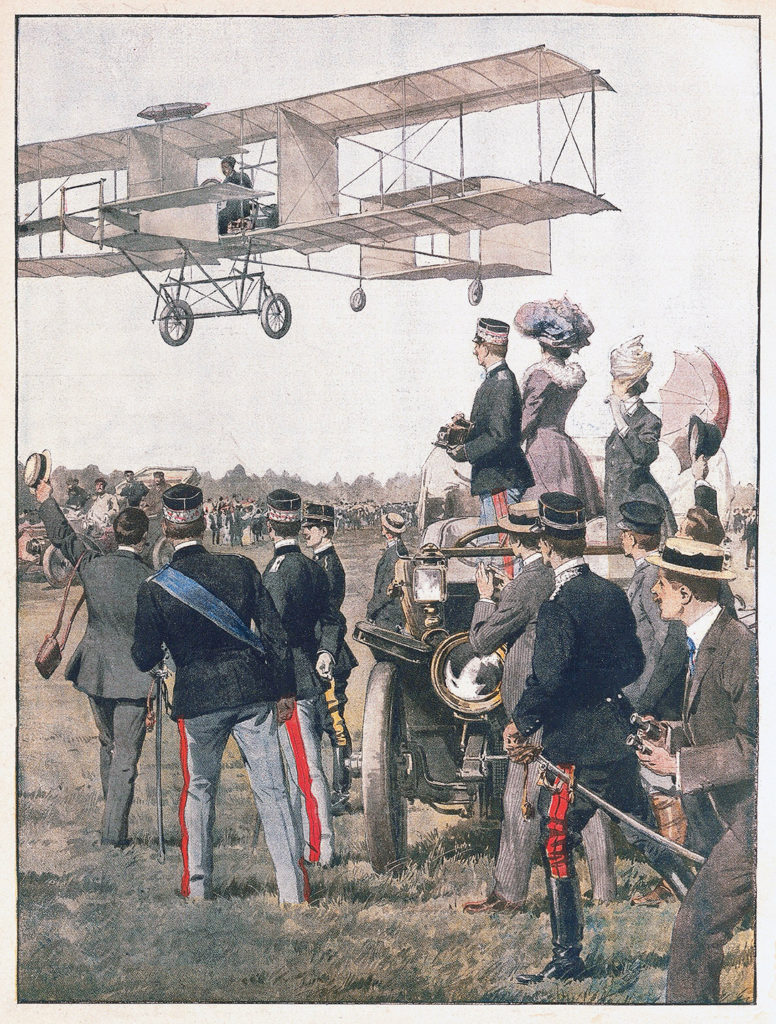

During the summer of 1908, Delagrange toured Italy with his airplane, flying an exhibition for King Victor Emmanuel III and setting distance and endurance records. On June 22, he flew 16 kilometers (9.94 miles) in 16 minutes and 30 seconds, setting an official distance and endurance record. The next day, he flew 17 kilometers (10.56 miles) in 18 minutes and 30 seconds.

On July 8 in Turin, Delagrange flew with his friend and travel companion, the artist and sculptor Thérèse Peltier, who wrote articles of the flights for French newspapers. Some sources say she was the first woman to fly in a powered heavier-than-air machine, though others credit Mademoiselle P. Van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie as the first after she flew with Farman in Ghent, Belgium, on May 31, 1908. Peltier, however, did enter the record books as the first woman to pilot an airplane when she flew Delagrange’s airplane 200 meters (656 feet) in a straight line at about 2.5 meters (8 feet) altitude in Turin.

Upon returning to France, Delagrange and Farman continued their friendly rivalry. In September, Delagrange flew 25 kilometers (16 miles) and by October Farman topped his distance by flying 40 kilometers (25 miles). Peltier continued accompanying Delagrange; on September 17 she flew with him on a 30 minute and 26 second flight. Though she continued to fly she did not pursue a license.

The world’s first air meet took place on May 23, 1909, at Port-Aviation, about 12 miles south of Paris. The meet drew only four aviators and though none of them completed the ten 1.2-kilometer (.75 mile) laps, Delagrange managed to fly a little over halfway and was declared the winner.

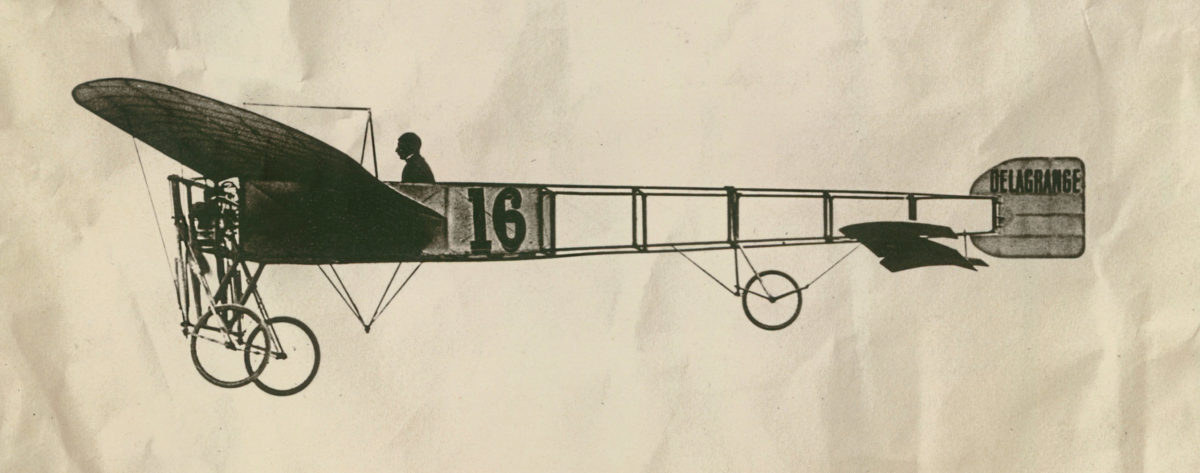

The first international air meet took place August 22-29 at Reims, France, and drew 22 aviators. The meet featured the inaugural Gordon Bennett Trophy competition. Delagrange was overshadowed by other entrants, but according to one source he placed tenth for speed and eighth for distance. He fielded three Blériot monoplanes and one Voisin biplane, having recruited Hubert Le Blon, Georges Prévoteau and Léon Molon as pilots. Delagrange flew his own Voisin-Delagrange III.

Delagrange also traveled to England to fly at a meet in Doncaster. Held in October 1909, the event was England’s first air meet. Delagrange’s team of fliers from Reims was there and Delagrange set a speed record of 49.9 mph, though it could not be officially approved since the meet wasn’t sanctioned by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. He also won the Nicholson Cup for the fastest five laps around the flying field.

On January 4, 1910, the airfield at Croix d’Hins, near Bordeaux, a site of early flying experiments, held an official inauguration ceremony. Delagrange agreed to demonstrate his Blériot XI, powered by a 50-hp Gnome rotary engine rather than the original 25-hp Anzani. The ceremony originally was scheduled for December, but bad weather forced a postponement. Weather remained poor on January 4 with strong gusty winds, yet Delagrange took to the sky. He completed two circuits around the field and was rounding a turn on his third circuit when the wings collapsed. Delagrange died in the crash, the first of several fatal Blériot accidents that would plague the machine. Grieving, Thérèse Peltier walked away from aviation forever. The field at Croix d’Hins eventually closed.

Delagrange’s death fueled skepticism about the new field of aviation. “The death of Léon Delagrange, crusht [sic] under the wreck of his falling aeroplane at Bordeaux last week, raises again the question whether the aeroplane is not to be classed with the tightrope and the ‘loop-the-loop,’ rather than to be considered seriously as a practical means of locomotion,” noted the January 15, 1910, issue of The Literary Digest. Despite such skepticism, flying machines advanced far beyond anything even Delagrange imagined and became much more than simply “the bicycle of the airs.”