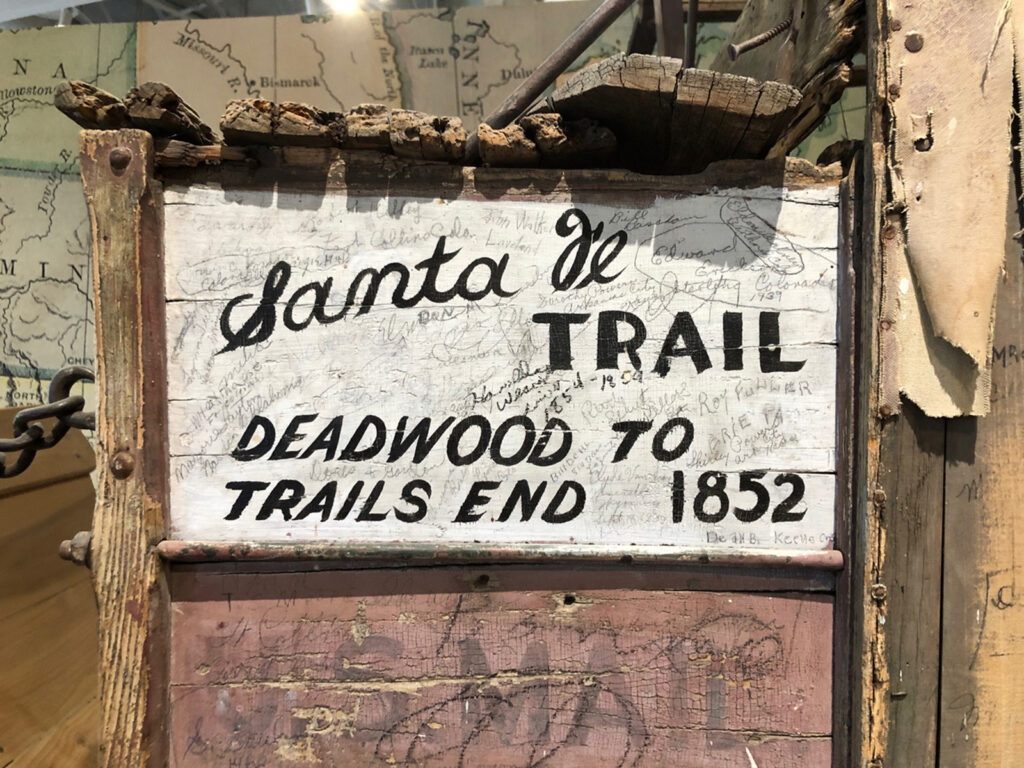

Center stage in a northern Colorado museum is an unmistakable symbol of the West. Faint lettering on the driver’s box of the historic stagecoach reads U.S. Mail, attesting to its original purpose, while covering nearly every square inch of its woodwork are scrawled signatures, hinting at its raucous second career in Wild West shows. Among the signatures is that of down-home humorist Will Rogers.

While it can prove challenging to chisel facts from Western lore, this coach and its storied past endures, thanks to Frank C. Miller Jr. The sharpshooter turned Wild West showman once described how he acquired the coach:

“In the late ’80s and ’90s it was on the ‘Bill’ show (meaning the Buffalo Bill circus) on his many tours, but as it became so old that it would not stand up under the hard knocks required of ‘Indian holdups,’ it was traded for a more modern model. I fought hundreds of Indian battles from the top of the coach myself on the shows. European royalty rode in the coach, as well as Teddy Roosevelt and President [William Howard] Taft, and I believe you will still find Will Rogers’ name written on the back.…When the new coach was put into use, I bought the old coach from Cody and sent it home and have owned it ever since.”

Built in 1874 by the Abbot-Downing Co. of Concord, N.H., the light coach is more correctly called a mud wagon. A basic, unglamorous conveyance, it was made to transport passengers and mail over rough-hewn trails. Given the lack of a paper trail tying the wagon to either Miller or Cody, it is difficult to verify Frank’s story. He may have glossed over the facts, but a kernel or two of truth remains.

A renowned marksman, trick shooter and roper, Miller claimed to have toured with Cody in Europe, though which tour is unknown. As he was 40 years younger than Buffalo Bill, Frank probably would have been too young to join any but one of Cody’s last European tours, between 1902 and ’06. The mud wagon would have been retired by that time, as period advertising featured the Wild West’s more elegant Concord stage, with its higher profile and oval body. Dubbed the “Deadwood Stagecoach,” the latter is on exhibit at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyo.

Franklin Carl Miller Jr. was the third of four children born to immigrant parents. His Danish father and Swedish mother had independently followed the promise of gold to the north-central Colorado mining settlement of Black Hawk, where they married in 1876, later moving to the growing frontier town of Fort Collins, where Frank was born on May 11, 1886. The Millers prospered, running a saloon, a mercantile store and, later, a garage.

Taking a page from Cody, showman Frank became a skilled self-promoter. Local newspapers are peppered with notices of his performances, dinner guests and encounters with notable figures, including a visit to Cody’s foster son, Johnny Baker. Miller worked for Zack Mulhall’s Wild West show and headlined with the Irwin Brothers’ Cheyenne Frontier Days Wild West, which billed him as the “Most Marvelous Marksman in the United States.” When that show closed in 1917, Frank bought a ranch northwest of Fort Collins and married Florence “Peggy” Leedle, a gal who loved the spotlight as much as he did. She performed on horseback, crooning songs, and they adopted a son, Franklin, who went by “Teddy.” Naming their spread Trail’s End, the Millers developed it into a dude ranch, offering fishing, Western entertainment and a menagerie of trained wild animals, including bears and wolves. Newspapers announced regular visits from such celebrities as humorist Rogers, circus performer and actor Fred Stone, sharpshooter Captain A.H. Hardy and novelist Rex Beach.

Miller held performances both on the ranch and in neighboring towns. Central to his show was the mud wagon, which he rode in parades and holdup re-enactments. When the wagon deteriorated, he had it loaded onto a flatbed trailer and performed from atop that.

Just when his show seemed to peak, Miller’s life went into a tailspin. First, wife Peggy left him. Next, at the tail end of the Great Depression, he lost Trail’s End to bankruptcy. Finally, the unthinkable happened. In 1946 son Teddy, who’d joined the Army, was killed in a motor pool fire while stationed in occupied Berlin. He was 19.

It was at that low point the mud wagon, among Teddy’s favorite family keepsakes, took on new meaning. As a memorial to his son and the six other soldiers killed in the fire, a grief-stricken Miller presented the coach to the city. It was initially housed in a small purpose-built brick building with a viewing window.

Today, most of the 150-plus visible signatures on the coach are difficult to read or trace, and many bearing earlier dates are questionable. While there is no way to verify the validity of Rogers’ signature on the upper left rear panel, neither can it be discounted. Miller and the humorist certainly knew each other. Most other signatures appear to be those of tourists or perhaps Trail’s End visitors or show hands. Most date from between the 1910s and ’40s and represent citizens of states across the West and Midwest.

Miller lived out his life in Fort Collins’ Linden Hotel, across the street from the red sandstone building that once housed the family saloon and store. In exchange for his room and board he painted Western scenes and visited schools, regaling young listeners with stories of the Old West and his encounters with Cody and Rogers. On Nov. 21, 1953, Miller, 67, died of a heart attack.

In the mid-1990s Miller’s memorial mud wagon underwent conservation. It has since been housed at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, where it symbolizes the many facets of the Old West. With its ties to mail and passenger service, Wild West performances, and perhaps even showman Cody and humorist Rogers, the mud wagon has gained the celebrity Miller had long envisioned.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Wild West magazine.