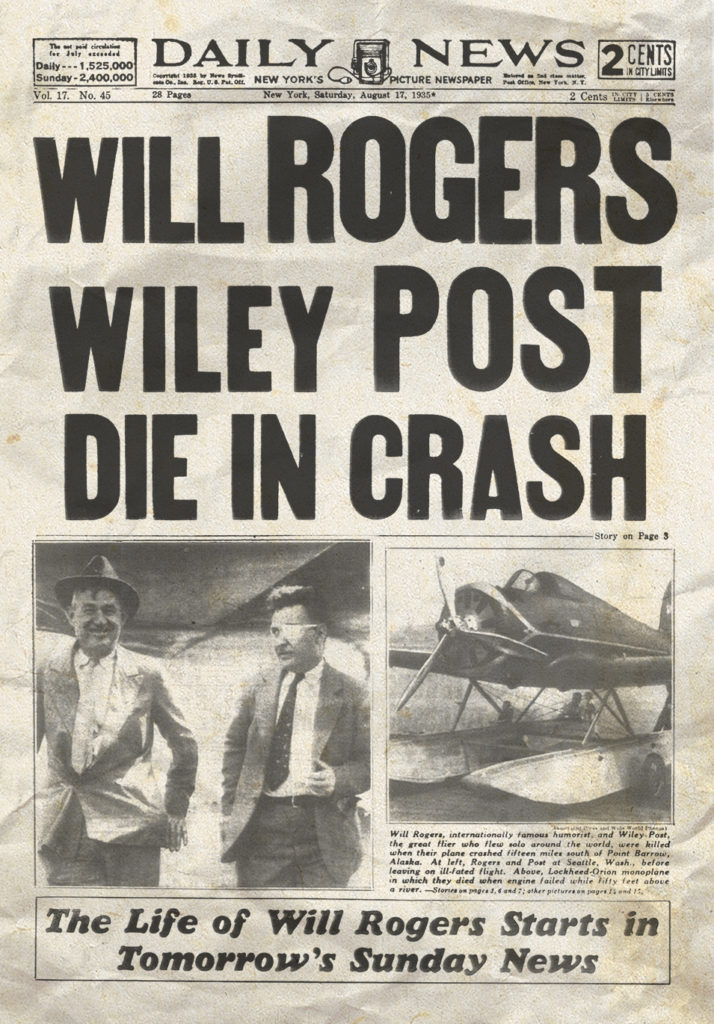

It was just after 7 p.m. local time on August 15, 1935, a frigid day of patchy fog on the far northwest coast of Alaska. Famed flier Wiley Post and his good friend and fellow Oklahoman, the celebrated humorist Will Rogers, were sloshing around the shallow waters of Walakpa Lagoon on the Chukchi Sea coast some 15 miles southwest of Point Barrow. Tiny, remote Barrow, on the most northwesterly point of the North American continent, was to be the jumping off place for their planned flight to Siberia and beyond.

They were behind schedule and anxious to get started. Because of poor visibility, Post had gotten lost on the six-hour jump from Fairbanks to Barrow and had been forced to put the floatplane down in the lagoon to get his bearings. The pair had landed near an Inuit family headed by Clare Okpeaha, who had closed his summer seal hunting camp and was waiting for a boat to Barrow. After Rogers explained they were lost, the Inuit, despite his broken English, pointed to the northeast and guessed the town was about “twenty or thirty miles” away—his concept of “English miles” was limited at best.

Post was loathe to lose another day waiting for better visibility, the marginal takeoff minimums be damned. He had come to think of himself as a master of any situation and his assuredness must have swept Rogers into the moment. After a half-hearted attempt by Okpeaha to dissuade the men from attempting to take off in such poor weather, Post and Rogers climbed back into their single-engine Lockheed Orion. Post started the engine and taxied the awkward, nose-heavy machine across the lagoon and positioned it nose-to-wind. Following a hurried engine run-up check, Post throttled up the 550-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine and lifted off in such an abrupt, steep manner that even Rogers must have been startled. With that last bit of recklessness, Wiley Post condemned them both to a trip into eternity.

Wiley Post is arguably the most unlikely of all the great aviation pioneers. He was a poverty-stricken, one-eyed ex-convict from Oklahoma who never finished junior high school but nevertheless went on to become a parachute jumper in a flying circus, a test pilot, discoverer of the jet stream, inventor of the pressurized flight suit, pioneer of the first autopilot and the first man to fly solo around the world. How did a man with such a checkered past and almost nonexistent formal education make his astounding engineering accomplishments?

Post was born November 22, 1898, in a modest farmhouse near Grand Saline, Texas, though Oklahoma, where he moved as a child, later claimed him as a “favorite son,” as it did Will Rogers. He quit school at 11, having decided he was “old enough to decide matters for himself.” He saw his first airplane at a county fair at age 14, when a Curtiss Pusher was the hit of an airshow. To top off the day, on the trip home Wiley rode in an automobile for the first time. Armed with his new-found love for machines, he took a seven-month auto mechanic’s course, graduating as a chauffeur and mechanic.

Post attended the U.S. Army’s radio school during World War I and went to France but saw no action. After his discharge, he drifted, winding up as an Oklahoma oil field roughneck, leading to his own unsuccessful attempt at becoming an “oil baron.” Unemployed, discouraged, but still fiercely ambitious, Post succumbed to desperate financial temptation and began hijacking automobiles in Grady County, Oklahoma. On April 2, 1921, the weekly Chickasha Star newspaper’s headline read, “Bandit Captured and Lodged in Jail.” Wiley was convicted of robbery and sentenced to ten years in the state reformatory. For reasons unclear, however, a sympathetic prison physician came to Wiley’s defense, and Post received parole on June 3, 1922.

Relieved, Post decided it was time he finally made good. He joined the Texas Topnotch Fliers, a flying circus, and became their star parachute jumper for $200 a jump. During this period, he gained a reputation as an utterly fearless aviator. But the work was intermittent; by 1926 he was back on an oil rig. Fate intervened when a roughneck’s sledgehammer sent an iron bolt into his left eye, which had to be removed. He used the settlement money he received to buy an airplane, but struggled mightily to gain his pilot license, no small feat with such a disability. Finally, after accumulating 700 hard-earned probationary flying hours, Wiley Post was awarded air transportation license number 3259 on September 16, 1928. When Texas oilman Florence C. Hall met Post, he was im-

pressed enough by his ability to hire him as his pilot. After that, flush with a new confidence coming from the association with Hall, Post began seeking the main chance.

Now began his incredible breakthrough into the national consciousness. Part of his motivation no doubt had to do with a desire to impress his new bride, 17-year-old Mae Laine, with whom he eloped in 1927, but most had to do with his own burning ambition. The opportunity he had been seeking presented itself in late 1928 when Hall sent Post to the Lockheed factory in Los Angeles to exchange his company’s Travel Air for a new Lockheed Vega. Hall named the sleek ship Winnie Mae after his daughter. Post was overjoyed, as it was an airplane designed to “go places and see things.” The coincidence of the name echoing his new wife’s must have been equally gratifying.

Unfortunately, that joy was short-lived. A downturn in the oil business forced Hall to give up the luxury of a private airplane and pilot and he sold the Winnie Mae back to Lockheed. Post received a break when Lockheed unexpectedly hired him as a test pilot. In June 1930, Hall re-hired Post and asked him to order a new Winnie Mae Vega, a seven-passenger monoplane with a 420-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine. Hall also approved Post’s entry into a 1,760-mile National Air Races Derby between Los Angeles and Chicago. Flying with famed navigator Harold Gatty, Post won the race—his first brush with national fame.

That was all it took for the always ambitious Wiley Post to up his game. Boldly, he announced plans to fly around the world in record time. Hall was in favor of the plan; the Depression had slowed his business, Post had plenty of time on his hands and the publicity couldn’t hurt. During the spring and summer of 1931, Gatty mapped out the journey while Post got his machine in tip-top shape. He made many modifications, especially the addition of extra fuel tanks and a special folding hatch atop the fuselage to enable Gatty to make critical celestial observations. The two men departed Roosevelt Field, New York, on June 23, 1931. After a series of incredible adventures, any one of which could have stopped them dead in their tracks, the duo arrived safely back at Roosevelt Field after eight days, 15 hours and 51 minutes—a new world record.

In less than three years, Wiley Post had been transformed from an unknown barnstormer into the world’s most famous pilot. And writing the foreword to Post and Gatty’s book about their flight was the world’s most famous humorist, Will Rogers, a “cowboy philosopher” who had become a beloved star of stage, screen and radio as well as a widely read newspaper columnist. Post and Rogers had met in 1925 and they had bonded almost instantly.

In 1932, subject to bouts of melancholia and worried he was sinking from public view—his one real avenue to financial success—Post settled on the idea of flying solo around the world. Incredibly, he somehow pulled that effort together, telling the newspapers in February 1933 he would do it with help from a new “robot” or “automatic pilot.” Post had a Sperry autopilot installed in the Winnie Mae and dubbed the new contrivance “Mechanical Mike.” He received permission to use this “risky” device on condition he not carry passengers, which of course was the whole idea. After modifications that included increasing the Winnie Mae’s fuel capacity, beefing up the range on his two-way radio mast and installing a more reliable ignition harness, Post was ready.

Early in the morning of July 15, 1933, Post took off from New York’s Floyd Bennett Field. He was wearing a white eye patch after having suffered severe headaches when his glass eye froze over Siberia two years earlier. His last words to his wife were a rather grim, “See you in six days or else.” Fortunately, the “or else” never materialized, though he didn’t make the six-day goal. Once again, Post’s combination of skill andluck held. Other highly capable aerial competitors were hot on his heels, but the “one-eyed superman” arrived triumphant back in New York on the evening of July 22, 1933. He had broken his own speed record by more than 21 hours—a total of seven days, 18 hours and 49.5 minutes.

The nation could not seem to do enough to express its delight in Wiley Post’s feat. The honors, awards and accolades continued for months; even President Franklin Roosevelt personally thanked him for his “courage and stamina.” New York mayor John P. O’Brien pinned a new gold medal on Post’s coat and compared him to globe-girdling explorers Ferdinand Magellan and Sir Francis Drake. Still, Post’s dream of great wealth remained elusive and, while he did make decent money endorsing such products as Camel cigarettes, it was not enough; he hungered for new ways to win acclaim. In particular, his use of the Sperry autopilot on the solo world flight had whetted his appetite for state-of-the-art scientific investigations.

He turned his attention to testing the “thin air”—the unexplored stratosphere, beginning around 30,000 feet. An opportunity came with the announcement of the 1934 MacRobertson Race from England to Australia, with a first-place prize of £15,000. Post intuitively understood his only chance to win the 12,500-mile challenge was to take advantage of the high-altitude winds that had recently been discovered by stratospheric balloon flights. It was clear the plywood-built Winnie Mae could not be pressurized; Post would need something like a deep-sea diver’s suit to protect him. With the help of the B.F. Goodrich Co., he developed a pressurized flight ensemble, dubbed at the time, “a man from Mars” suit. It was constructed from a rubberized parachute material, including a plastic vision plate encased in an aluminum helmet. After getting mixed results from the tests of several suits, Post reached 40,000 feet on September 5, 1934. He was the first person to fly in a pressure suit, as well as the first to use liquid oxygen for breathing. Post had proved operating in the stratosphere was “a definite reality, with practical equipment.”

By this time, Post’s adventures and headlines about his proposed stratospheric dashes across the continent were galvanizing the public, subsuming his push to enter the MacRobertson Race. Additionally, to Post’s delight, Will Rogers had renewed their friendship, having become increasingly interested in his activities. As it happened, Rogers had been present when a pressure suit-equipped Post attempted a high-altitude, 375-mph flight from Burbank to New York on February 22, 1935. Post had to make a forced landing shortly after takeoff, with engine sabotage strongly suspected—Post was picking up jealous competitors along with his growing commercial endorsements. Rogers wrote: “[Saw] Wiley Post take off.… He soon had to land. He brought her down on her stomach [the gear had been dropped on takeoff for streamlining], that guy don’t need wheels.”

After a failed second attempt at the transcontinental speed record on April 14, Rogers suggested the aging Winnie Mae be retired and Post given tangible help in his scientific pursuits: “Wiley Post…cant break records getting to New York in a six-year-old plane, no matter if he takes it up so high that he coasts in.… So when Wiley gets ready to put her in the Smithsonian we all want to give him a hand.” The appeal worked, Congress appropriated $25,000 for the museum’s purchase, but the money went to Hall, the airplane’s owner. Meanwhile, the impulsive and always resourceful Post had somehow pulled together the necessary additional financing to purchase a new airplane.

Post did not give his new airplane a name, but experienced pilots and mechanics had taken one look at this one-of-a-kind “unusual-looking” plane and dubbed it “Wiley’s Orphan,” or alluding to its rather illegitimate origin, “Wiley’s Bastard.” Painted “Waco Red” with silver trim, it had a second-hand Lockheed Orion 9-E Special fuselage married to an orphan Lockheed Explorer wing and a 550-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine. Its retractable gear could fit into the low Lockheed wing, but the airplane could also be fitted with pontoons. The design’s chief advantages were greater speed and a high load capability. The chief disadvantage, by far, was a too-far-forward center of gravity, causing nose heaviness and a built-in tendency to assume a diving attitude. With pontoons attached, the problem was exacerbated. A Lockheed engineer had even warned Post, “you’ll be in trouble if there is just a slight power loss on takeoff.” Increasingly overconfident, even complacent, Post ignored him, keeping the plane’s imbalance a secret when applying for an air worthiness certificate on July 23, 1935.

A hint of what Post planned to do with his new machine emerged when a reporter apparently overheard a conversation and wrote a story that Will Rogers and Wiley Post were secretly planning a trip to Siberia via Alaska. It rang true to many; Rogers had long expressed a desire to visit the Far North. In addition, Post had obtained financing to survey potential air routes from Alaska to Russia.

Meanwhile, Will Rogers was at his ranch in Pacific Palisades, California, dithering over whether to commit to this Alaskan “vacation,” as he called it. His wife, Betty, opposed the trip out of fear the men would get lost over the trackless Siberian wastes. Will calmed her with assurances that he was only committing to visiting Alaska. Probably, he said, he would say goodbye to Post there and return home. Betty could see how badly her husband wanted to go, so she acquiesced.

The two men kept a public silence about their proposed venture as Rogers put the finishing touches on his last movie, Steamboat Round the Bend. By August 4, the secret was out; national headlines announced that beloved humorist and movie star Will Rogers would fly to Alaska with Wiley Post. Their journey began with a takeoff from Seattle’s Lake Washington, adjacent to Boeing Field, on Wednesday morning, August 7, 1935. Post and Rogers landed on Juneau’s Gastineau Channel a thousand miles and eight-and-a-quarter hours later. There an old friend of Post’s, famed Alaska pilot Joe Crosson, greeted them. A Juneau newspaper noted the reaction of the local bush pilots, “[who shook] their heads in doubt…at the plane.” Rogers was the soul of hospitality when asked about their plans. “Wiley and I are like a couple of country boys in an old Ford—don’t know where we’re going and don’t care,” he said. Post, however, was irritable, snapping at reporters, “We’re going to stay [in Juneau] until we get ready to takeoff!”

When weather finally allowed the journey to continue, a local airline mechanic observed, “Post was not a good seaplane pilot…too abrupt on takeoff and pulled up too steep.” Following goodwill stops at Dawson, Aklavik and Anchorage, the two tourists departed Fairbanks on August 15, bound for Point Barrow. Post continued to exhibit erratic flying behavior, especially regarding fuel management and dangerous scud running—all of which Rogers understood nothing. Or cared; he was loving every minute of his time in Alaska.

On the takeoff from Fairbanks, Post had made another dangerously steep departure. One bush pilot noted that “if the engine [had] quit, he’s a goner.” The weather was forecast bad all the way, but Post forgot his pledge not to fly Rogers “in or above cloud or fog bank.” He was now “making his own weather.” In fact, it was only due to his great skill and continued good luck that he’d made it as far as Walakpa Lagoon.

After a hurried conversation with the Okpeahas, Post and Rogers got back into the red Orion and took off into the fog and mist, with Post once again, inexplicably, hanging by the propeller in a steep ascent. He banked sharply at two hundred feet and there was an explosion “like the sound of a shotgun,” as Okpeaha testified. The engine stopped, very possibly due to fuel stoppage induced by the twisting takeoff. In their book Will Rogers & Wiley Post: Death at Barrow, Bryan and Frances Sterling wrote that the airplane “continued to somersault, tumbling downward, [then hitting] the shallow water [and] shearing off the right wing, breaking the floats, and falling on its back.” Both men were instantly crushed to death, their bodies so mangled their wives were told white lies about their actual condition. Okpeaha set out running to Port Barrow and arrived there with news of the crash five hours later.

Tributes poured in from all over the disbelieving world. The newspapers concluded that the cause of the accident was carburetor icing resulting in “the engine stalling.” The truth was the airplane should never have been licensed to fly in the first place. The government investigation, the Sterlings wrote, became “a travesty” that covered up the regulatory negligence of the Bureau of Air Commerce. The government’s secret rationalization: If the famous Wiley Post was not flying safe, was anyone? Despite that contemporary, and successful, coverup, sufficient documents survived for later researchers to at last reveal the real cause: pilot error. Wiley Post’s luck had finally run out.