“Fixin’-to-Die-Rag” derailed his promising musical career. But it led Joe McDonald to become a fierce champion for Vietnam veterans.

IT WAS TIME FOR A SECOND ACT on the second day of a music festival at a sprawling dairy farm in upstate New York in August 1969, but Santana, a relatively unknown band scheduled to go on stage next, was having trouble getting it together. So the emcee asked a performer hanging around backstage to go out and kill a little time. Reticent at first because his band was to play later that weekend, the singer gave in after he was handed a Yamaha FG-150 guitar and ushered onto the stage. After the audience ignored the eight songs he sang, he stepped off the stage momentarily, at which point his tour manager told him the way to seize the crowd’s attention was to perform the number he was saving for the next night.

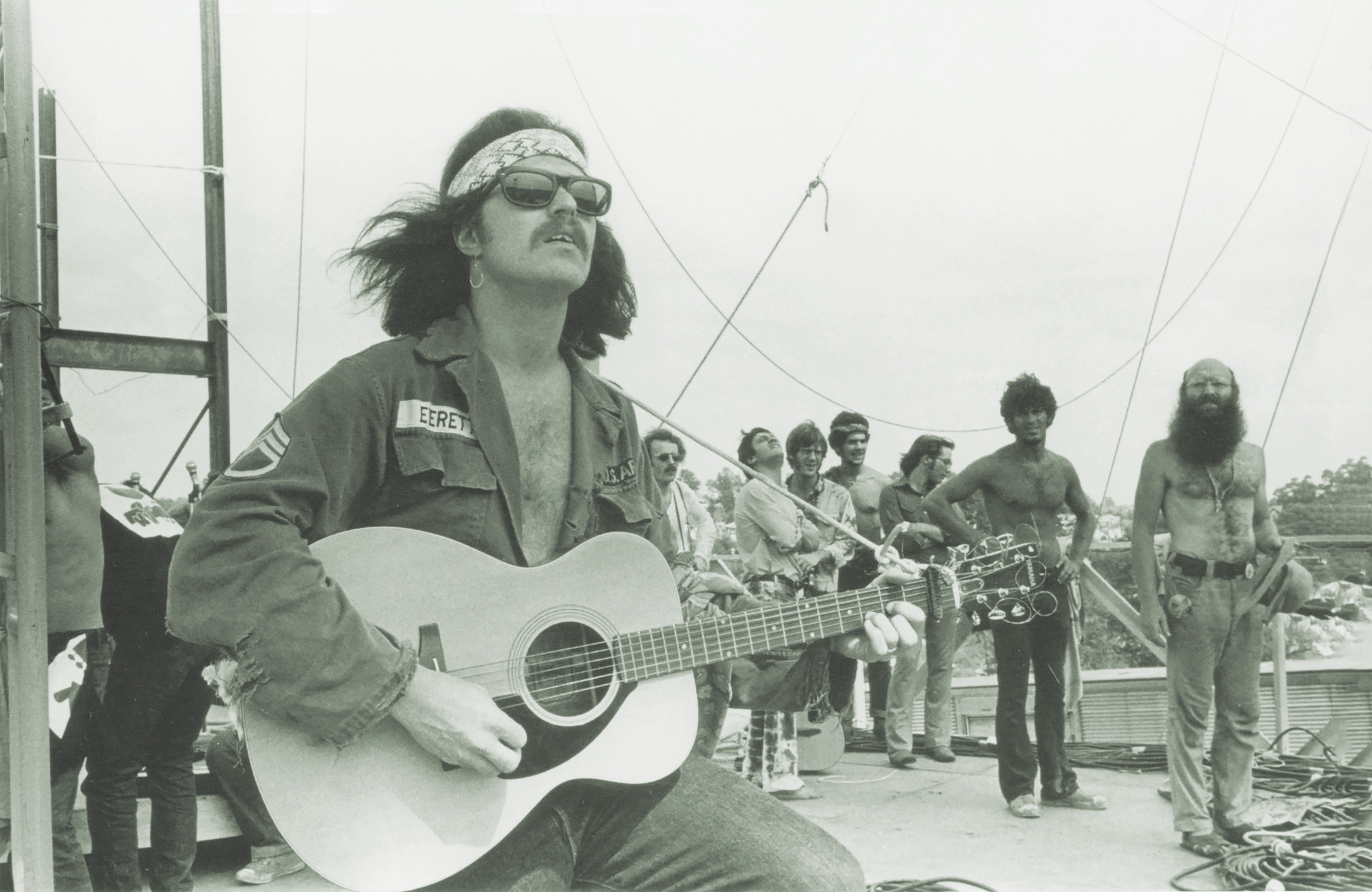

The singer walked back on stage, alone. Decked out in a regulation army jacket, with long hair, a hoop earring, a paisley headband, and a handlebar mustache, he called out to the masses, “Give me an F!” With that, the infamous Woodstock crowd of “half a million strong” rose to their feet and joined in Country Joe McDonald’s antiwar cry, chanting along from the opening expletive to the “Whoopee! We’re all going to die” capper. Captured in Michael Wadleigh’s Oscar-winning 1970 documentary, Woodstock, the three rousing minutes of McDonald’s acoustic version of the “Fish Cheer & I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” became the Vietnam War protest anthem.

“I never had a plan for a career in music, so Woodstock changed my life,” says McDonald, who lives in Berkeley, California. “An accidental performance of ‘Fixin’-to-Die,’ a work of dark humor that helps people deal with the realities of the Vietnam War, established me as an international solo performer. Then the movie came out and the song went on to become what it still is today.”

IN FEBRUARY 1986, SOME 17 YEARS AFTER WOODSTOCK, a nonprofit organization supporting various outreach and counseling programs for Vietnam veterans held its first major fundraising concert at the Forum in Los Angeles. The lineup included such stars as Kris Kristofferson, Stevie Wonder, Brian Wilson, and Woodstock veterans Neil Young, Graham Nash, John Sebastian, Richie Havens, and Sha Na Na. The most intriguing performer on the bill, however, was the man many people considered to be one of the country’s leading antimilitary radicals—the very same folk singer whose flippant use of obscenity about the Vietnam War derailed a promising musical career but also led him to become a fierce lifelong champion of those who served their nation in wartime.

Nobody in the audience at the Forum was surprised that Country Joe McDonald opened the night with “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag.” First released in 1967, his signature song was repurposed in 1986 as the first track on Vietnam Experience, an album he recorded as veterans of the war were finally receiving public recognition. The 12 songs on the LP included “Foreign Policy Blues,” “Agent Orange Song,” “Vietnam Never Again,” and, in true Country Joe fashion, “Kiss My Ass.” One song in particular, though, stands out on the album: “Welcome Home,” a spiritual callback to “Fixin’-to-Die” complete with the same whimsical calliope circus arrangement, the call-and–response chanting, and lyrics written specifically for those who wore the tropical fatigues.

“We had Armed Forces Radio and pirate stations like Radio First Termer, which was run out of a brothel, and music was our lifeline,” says Douglas Bradley, a Vietnam veteran and coauthor of We Gotta Get Out of This Place: Music and the Vietnam Experience. “Whether you stayed or served, participated or protested, knowing we were listening to the same songs kept us connected. Music helped keep a lot of us alive in Vietnam.”

Although it’s never been as well known as its antiwar predecessor, “Welcome Home” embodies McDonald just as much as the defiant rallying cry he delivered to Woodstock Nation. More than a decade after the fall of Saigon, “Welcome Home” had a simple message: Americans needed to make peace with the soldiers sent to Vietnam (and with those who fled to Canada and beyond) and to do right by them for what the country put them through. It wasn’t a chart topper, but it had a profound impact on the songwriter himself.

“‘Welcome Home’ was a landmark in my life regarding the Vietnam War,” McDonald says. “I had to put aside my anger and attitude and write a sincere song, for both veterans and those who resisted, to start the healing process. In writing it, the healing process began within myself, which was a big surprise. It changed me.”

McDonald, at 77, hasn’t lost any of the rage he feels toward the politicians and generals who got the United States into the Vietnam War—he reserves special disdain for General William Westmoreland—but he’s always been on the side of the rank-and-file, the working-class people who bear the brunt of the fighting. Having grown up in a socialist family, he’s always seen soldiers as lunch-pail workers who aren’t able to collectively bargain for themselves. Yes, he’s opposed the majority of post–World War II American military actions, but he’s not a pacifist; never has been. In fact, he considers himself a veteran first and a hippie second, because unlike most musicians of the Vietnam protest era, he served his country in uniform. Even though a military career didn’t exactly align with his upbringing.

BORN A “RED DIAPER BABY” (a child of parents who were members of the U.S. Communist Party), McDonald was raised in a left-wing household in Southern California filled with the sounds of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. As Joe entered his teenage years, the family’s middle-class life was upended when his father, a lineman for Pacific Bell Telephone Company, was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and lost his job. It wasn’t the first time that McDonald’s old man butted heads with the federal government.

“My father enlisted between the two world wars,” McDonald says. “He was 16 when he joined the cavalry. As a farm boy he must have loved it, but they kicked him out after a few weeks once they caught on to his age, and sent him packing with a $35 check, which I still have. During World War II my father was eligible to be drafted, but J. Edgar Hoover thought he would be a troublemaker and personally kept him out of the war. My father never knew that because the FBI file wasn’t released until after he died.”

Growing up, McDonald focused on music—first classical, later rock ’n’ roll—but he didn’t have much of a plan after he graduated from high school in El Monte, California. One day he was walking downtown and saw a navy recruitment poster with a sailor in whites on an aircraft carrier, windswept as he waved flags. The job description read signalman. McDonald thought it looked cool, so he went in and talked to the recruiter, who told him that eventually he could become a jet pilot. McDonald needed parental permission to enlist, and to his shock his radical leftie mother signed off on the idea.

McDonald signed up for the navy’s now-defunct “Kiddie Cruise” program, which gave 17-year-old enlistees a shorter hitch, ending on their 21st birthday. Unfortunately, his dream of becoming a signalman and perhaps a jet pilot was dashed at boot camp in San Diego when, after a superior mistakenly wrote down “air control,” a totally different program, McDonald was sent to school in Olathe, Kansas. Halfway through the course, he asked when he would be learning how to wave signal flags only to be told that he was in training to be an air traffic controller.

McDonald would spend two years at Naval Air Facility Atsugi in Japan’s Kanagawa Prefecture, about 30 miles southwest of Tokyo. The air base served as one of the launching pads of the secret U-2 missions. (Hallowed ground for conspiracy theorists, it’s where a marine named Lee Harvey Oswald obtained top-secret security clearance and monitored radar for the American spy planes.) The missions were central to American intelligence efforts, but no matter how hot the Cold War, McDonald quickly cooled on doing his part as an air traffic controller.

“I went up on the tower for a few days, but it was too stressful, so I ended up spending my time in flight operations providing maps and weather reports to the pilots,” McDonald says. He found his job boring and felt trapped, but he loved Japan. He lived off base part of the time, had a Japanese girlfriend, went sightseeing, immersed himself in the culture, and learned local songs, which he still sings to his grandson. But when his time was up, he was ready to go home.

“I was pretty good at operations, so they asked me to reenlist, but I got out with an honorable discharge,” McDonald says. “It was the right time, because if they had sent me to Vietnam, there was nothing I could do about it. You do not want to go to a military prison.”

AFTER HIS DISCHARGE FROM THE NAVY, McDonald tried college for a few semesters but dropped out and landed in Berkeley. It was the tail end of the Free Speech Movement, which soon morphed into the antiwar movement. McDonald doesn’t recall reading about Vietnam in the newspapers or seeing combat scenes on television in those early days of the war; he learned about it through protests in the Bay Area. In the counterculture spirit, he started a magazine, Rag Baby. At one point he put out an “oral issue” by making 100 copies of a 7-inch extended play record that were made and sold one at a time. It included the first recording of “Fixin’-to-Die.”

“I was inspired to write a folk song about how soldiers have no choice in the matter but to follow orders, but with the irreverence of rock ’n’ roll,” McDonald recalls. “I banged out ‘Fixin’-to-Die’ in half an hour. It’s essentially punk before punk existed.”

THE ACOUSTIC SKIFFLE RECORDING of “Fixin’-to-Die” didn’t include the F-I-S-H cheer, although it did feature random machine gun fire throughout. In 1966, following Bob Dylan plugging in at the Newport Folk Festival, McDonald and his partner, Barry “the Fish” Melton, decided to move away from their informal folksy jug-band music and become a full-time rock band. The psychedelic sound of Country Joe and the Fish captivated the local scene. By December 1966 they had a recording contract with Vanguard Records, progressive home to the Weavers and Joan Baez.

The band recorded and released two albums in 1967, the first of which, Electric Music for the Mind and Body, didn’t include the future showstopper with the stanza about being one of the first to “have your boy come home in a box.” Maynard Solomon, the president of Vanguard Records, believed that the antiestablishment bent of “Fixin’-to-Die” would rule out any radio play for Country Joe and the Fish. The tune was saved to be the title track of the band’s second album that year, I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die. During the recording session, McDonald made a spur-of-the-moment decision to kick off the song, and thus the album, with a bit of the old rah-rah. The “F-I-S-H cheer,” which would soon lead police to stake out the band’s gigs, was born. Initially the song wasn’t more popular than anything else the band released, which included other protest songs like the Lyndon B. Johnson mockery “Superbird.”

Things changed in the summer of 1968, at the Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park, when the band’s drummer, Gary “Chicken” Hirsh, suggested spelling out the f-word in its cheer in place of F-I-S-H. A true act of rebellion, it fired up the thousands of New York City fans but also cost the band some major exposure. The Ed Sullivan Show canceled their appearance, and Country Joe and the Fish were permanently banned from the program. (They got to keep their fee of $2,500, McDonald says, noting that “the only band paid not to play Ed Sullivan” used to pop up on TV quiz shows.)

The new “gimme-an-F” cheer would cost McDonald even more later. In 1969, in Worcester, Massachusetts, a warrant was issued for his arrest for inciting the audience to lewd behavior—he’d eventually pay a $500 fine—and the next night some 75 police officers with billy clubs, sidearms, and Mace welcomed the band to Boston. They skipped the chant that night, but according to a story McDonald told on a live album, they dropped an f-bomb on the cops as a post-show salutation. The sneering profane lyrics destroyed McDonald’s chances at becoming a Top 40 staple, but he says he has no regrets about the song.

“The fuck cheer really barred me all over, even from the left-wingers, who ultimately didn’t want anything to do with me because I was with these coarse and crude Vietnam veterans,” he says. “Trying to speak nice language when talking about the Vietnam War is ridiculous; my attitude and lyrics were the same as the soldiers in combat.”

According to Bradley, the song really did have meaning for many who served in the jungles of Vietnam. So whatever McDonald lost as a recording artist, he gained as a staunch advocate for veterans.

“We sang ‘Fixin’-to-Die’ in Vietnam,” Bradley says. “I mean, when you get a group of soldiers together belting out ‘one-two-three what’re we fightin’ for?’ with gusto, you realize the validity of what Joe had written. McDonald understood that when you are in the worst traumatic experience of your life, laughter in the form of gallows humor might be exactly what you need to survive instead of killing yourself, killing someone else, or going crazy.”

McDonald says he recently met a Vietnam veteran who told him that a dying friend’s last words were, “Whoopee, we’re all going to die.” Another time, he says, a soldier who spent five years in the Hanoi Hilton told him that the Viet Cong would sometimes let the POWs listen to music and every time he heard “Fixin’-to-Die,” it boosted his resolve.

It isn’t just as a performer that McDonald has shown his commitment to improving the lives of veterans. He was among the soldiers who would get together to talk about their war experiences. They basically shared their psychic wounds of posttraumatic stress disorder, which wouldn’t be officially recognized until 1980, thanks in large part to Vietnam vets looking out for one another. McDonald heard lots of horror stories over the years—so many, in fact, that he began to have nightmares about them. Once, while running the Bay to Breakers footrace in San Francisco with a Vietnam vet friend, he envisioned the Viet Cong chasing them from behind.

“I ran faster, and I finished,” he says with a laugh. “Career-wise, the song closed a lot of doors for me, but it opened others, and my job became representing veterans. I never dreamed I’d be walking point on this issue, but here I am. I’m proud of it.” MHQ

Patrick Sauer has written for the New York Times, GQ, Smithsonian, and many other publications.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artists | The Irreverent Anthem

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!