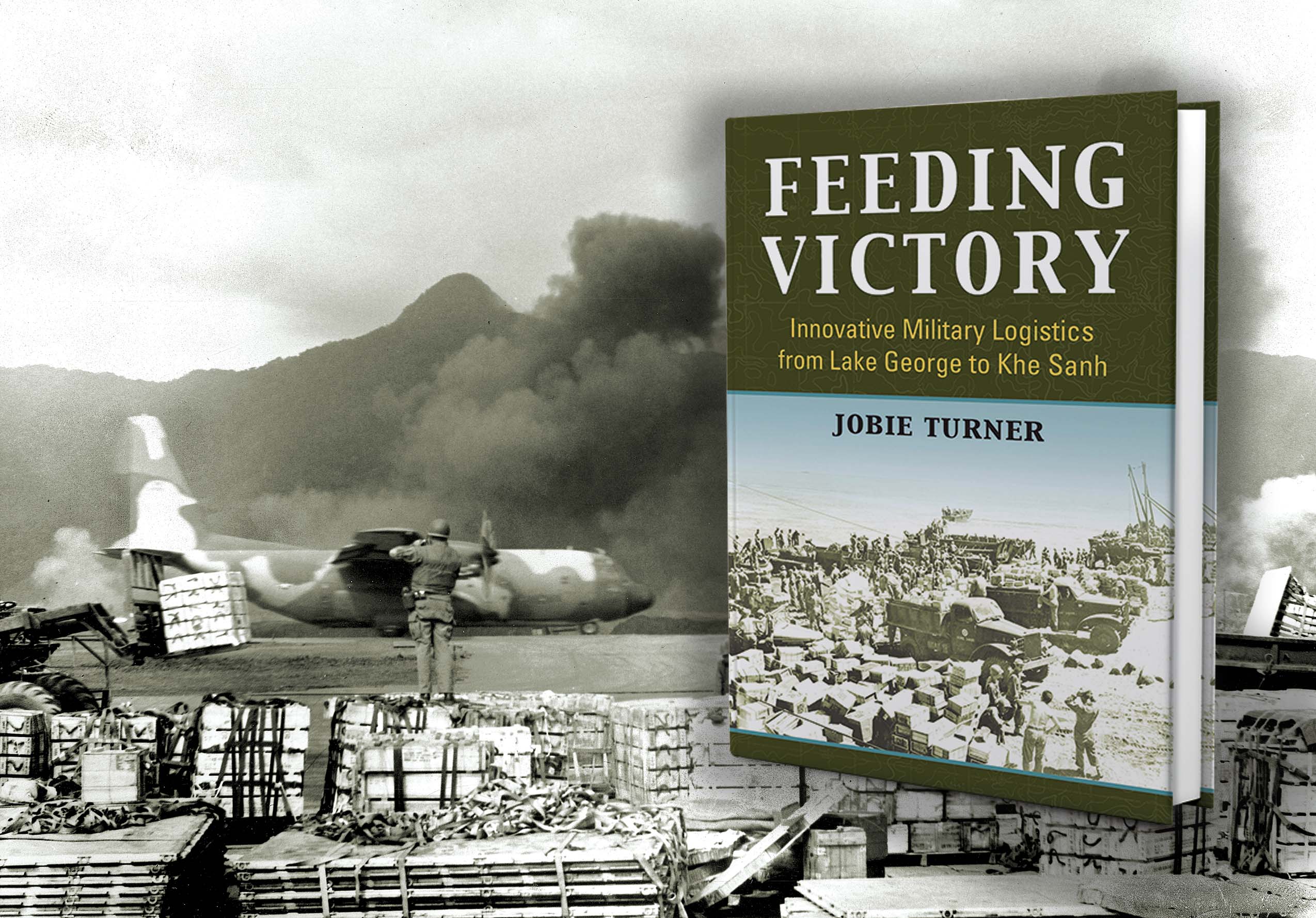

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower famously observed that “battles, campaigns, and even wars have been won or lost because of logistics.” Feeding Victory: Innovative Military Logistics from Lake George to Khe Sanh, an intriguing title from Air Force Col. Jobie Turner, explores the wisdom of those words and the impact of logistics on three centuries of armed conflict.

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower famously observed that “battles, campaigns, and even wars have been won or lost because of logistics.” Feeding Victory: Innovative Military Logistics from Lake George to Khe Sanh, an intriguing title from Air Force Col. Jobie Turner, explores the wisdom of those words and the impact of logistics on three centuries of armed conflict.

Defining logistics as the “combination of transportation and supply for a fighting force,” Turner focuses on four technological eras and selects a handful of battles and campaigns that best illustrate the role of logistics in each of those historical ages. The four-year campaign (1755-59) to wrest control of New York’s Lake George from the French and their Native American allies, for example, severely tested the ability of the British to supply their forces in the pre-industrial era. Turner also discusses the influence of technology and logistics in warfare during historical periods encompassing World War I, World War II and Vietnam.

In Vietnam, Turner homes in on the communist siege of the U.S. Marine base at Khe Sanh. Following months of debate, in January 1968 the North Vietnamese Army launched the Tet Offensive, nearly simultaneous attacks on dozens of cities across South Vietnam. The North believed the attacks would foment an insurrection and cripple the government in Saigon. To draw American troops away from urban areas before the attacks began, communist units laid siege to Khe Sanh, a remote outpost near the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam.

NVA planners, Turner writes, believed the Americans lacked the resources required to fight effectively in the cities and in the countryside at the same time. Similarly, Communist Party First Secretary Le Duan naively suggested the U.S. economy, the world’s largest, could not sustain an expeditionary army fighting half a world away.

North Vietnam, a small impoverished nation propped up by generous support from China and the Soviet Union, developed a surprisingly sophisticated logistical system. By 1967, Hanoi had transformed the Ho Chi Minh Trail, running through supposedly neutral Laos and Cambodia, into a network of routes and way stations capable of accommodating a fleet of 2½-ton trucks that delivered troops and supplies to communist forces fighting in the South. At Khe Sanh, communist logisticians moved two NVA divisions (roughly 20,000 troops) and enough food, arms and ammunition to conduct a prolonged siege of the Marine base.

Critical of static defensive positions, the Marines questioned whether Khe Sanh could be adequately supplied during a major attack and recommended abandoning the base in the summer of 1967. However, Army Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the overall commander of U.S. ground forces in Vietnam, ordered the Marines to hold the base. He welcomed the opportunity to bring American firepower to bear on the large enemy force congregating around the base and viewed the isolated outpost as a potential staging area for a future invasion of Laos.

Shortly after midnight on Jan. 21, 1968, the North Vietnamese assaulted Marine positions on Hill 861 to the north of Khe Sanh. Later that morning, the NVA shelled the main base. Turner, recounting the hellish 77-day siege that followed, notes that the struggle “resembled the Western Front in 1917.” As Westmoreland predicted, American firepower, aided by an advanced targeting system that tracked enemy movement, prevented the NVA from overrunning the beleaguered garrison.

“At Khe Sanh,” Turner explains, “the ability of American aircraft and artillery to pin down the NVA blunted their offensives, halted their logistics, and kept the NVA from their food.”

Marshaling the combined resources of several services, the Americans hurriedly deployed fixed-wing transports and helicopters to resupply—entirely by air—the 6,000 Marines defending Khe Sanh and the surrounding hills.

Contrary to misguided communist assumptions, the United States not only was able to afford the financial costs of a war in Southeast Asia, but could also arm and supply friendly forces in any theater of the conflict.

In April, a joint U.S. Army-Marine operation ended the siege. “Though the United States won at the game of supply and inflicted heavy losses on the NVA at Khe Sanh, they still lost the war,” Turner acknowledges. “The narrative of the small third-world country, besieging the Marines at Khe Sanh and attacking U.S. and [South Vietnamese] controlled cities in South Vietnam, was enough to turn American public opinion against the war.”

Turner, incidentally, misses the mark when he asserts that the war in South Vietnam was a “counterinsurgency.” The conflict actually combined main-force war elements and a well-entrenched military-political insurgency. Nevertheless, policymakers and military leaders alike would do well to read Feeding Victory. V

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: