[dropcap]A[/dropcap] Japanese guard’s clipped command broke the dawn silence on Corregidor, the tiny pollywog-shaped island afloat in the western approach to Manila Bay. “Standing!” he barked at the 200 ragtag men sleeping fitfully alongside the crossties of a rail line threading Corregidor’s eastern tail. Like the other POWs facing their first full day of enemy captivity, Edgar Doud Whitcomb, 24, rose to his feet slowly and warily, not knowing what to expect.

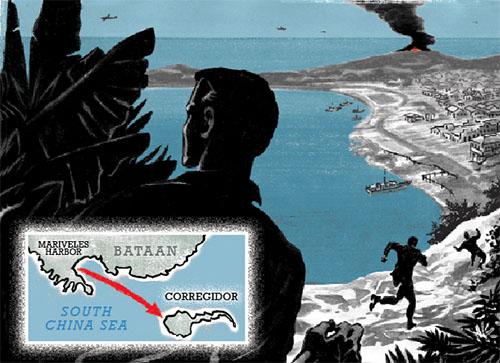

North across the channel, Ed could see the shores of Bataan and, beyond, the towering summit of Mount Mariveles. Having once fled Bataan with the Japanese at his heels, Ed had never imagined returning. But now he found himself instinctively gauging the distance he would have to swim to get there—and what he would do once he reached its dubious sanctuary.

It was May 8, 1942. For several months, Corregidor—“The Rock”—had held out as Japanese invaders laid siege. During the struggle, Whitcomb, a U.S. Army Air Forces B-17 navigator, had fought on foot as had so many other airmen and sailors. Immediately after the Rock capitulated to the Japanese on May 7, Ed’s captors assigned him to a work party and marched the group toward Kindley Landing Field, Corregidor’s airstrip. Now, after scant sleep and no food, the POWs began repairing Kindley’s cratered runway for Japanese use. As he labored under the broiling sun over the next two days, Ed clung to a singular imperative.

Escape, somehow escape.

ED HAD REACHED THE PHILIPPINES seven months before with the 19th Bombardment Group. The circuitous flight from California’s Hamilton Airfield to Luzon’s Clark Field exceeded 6,000 miles, mostly over open ocean with only celestial signposts—just the sort of bold journey that fired Ed’s imagination. At 14, Ed had left his Hayden, Indiana, home one Sunday morning determined to see the outside world. His six-week hobo odyssey along the Eastern Seaboard ended with a vagrancy charge and sentencing to a North Carolina work gang. Ed’s mother had to wire funds to bail him out, but he returned neither shaken nor ashamed. He had learned to navigate the uncharted—and realized a passion for it.

The Philippines was bracing for war when the 19th touched down at Clark in October 1941. As Ed’s squadron flew reconnaissance near Japanese-held Formosa, though, he wondered how the putative enemy could presume to challenge them. “Their aircraft were vastly inferior,” he later wrote in a memoir. “Our B-17s could fly beyond the reach of the Jap’s anti-aircraft and planes, and we could pinpoint targets and destroy them with miraculous accuracy.”

Japan’s riposte came from a clear afternoon sky on December 8—December 7, Hawaiian time—as dozens of enemy bombers and strafing fighters savaged Clark. Not much was left afterward. “Crews standing by their planes were destroyed along with the ships,” Ed recalled. “Four bodies beside our own ship were charred beyond recognition.” Within two weeks, Japanese troops invaded Luzon, the largest and most populous of the Philippine Islands, and pressed forward until, on December 23, the grounded remnants of the 19th Bombardment Group joined a mass retreat south to Bataan Peninsula.

Conditions there worsened through weeks of artillery barrages, strafing attacks, dwindling supplies, and rampant disease. “Rations were reduced by half and…half again,” Whitcomb wrote. “Tropical diseases took their toll until about half of our units were not able to function.” Whitcomb was one of the felled, catching malaria. Finally on April 8, defenders withdrew to Bataan’s very tip. After an all-night journey, the southbound fugitives encountered northbound vehicles trailing white bedsheets. “At first, we could not comprehend,” Whitcomb recalled. Then they realized: the bedsheets were white flags.

Even as most Americans and Filipinos obediently surrendered, Ed contrived escape. He and two squadron members commandeered a vehicle, drove it east to Mariveles Harbor, and hopped aboard a motor launch bound for Corregidor, a longtime military fortress about three miles off southern Bataan. Reaching its north shore, they sprinted for the Malinta Tunnel, Corregidor’s huge, bomb-proof command center. “It was so easy,” Ed marveled.

He had no way of knowing it then, but he had just escaped an infamous atrocity. Bataan’s 70,000 captives—many suffering from wounds, malaria, and dysentery—were about to embark on a 70-mile death march. Thousands of prisoners would die en route; thousands more succumbed at Camp O’Donnell, a squalid POW compound.

Weeks later, as Ed Whitcomb contemplated the swim back to Bataan, he grasped a wartime reality: full freedom required constant escape.

ON MAY 10, 1942, after Ed’s POW contingent had finished repairing Kindley Landing Field, their captors marched them to a flat expanse on the south shore of Corregidor. Known as the 92nd Garage Area, it had once been the motor pool for the 92nd Coast Artillery Regiment. There, a concrete-floored, crescent-shaped arena overflowed with POWs. A partially demolished garage housed the sickest and most seriously wounded. The rest—as many as 12,000 American and Filipino airmen, soldiers, sailors, and Marines—sat exposed or under makeshift shelters.

The captives received no food beyond a meager daily rice allotment. A single quarter-inch pipe supplied drinking water. Open-air latrines swarmed with vermin; dysentery was rampant. The surrounding cliffs trapped and intensified the heat and the only available relief was to soak in Manila Bay’s shallows under watchful Japanese eyes.

Escape seemed futile but, for his part, Ed was fortunate to encounter a like-minded U.S. Marine captain named William F. Harris. A rifle company commander in the 4th Marines on Corregidor, Bill immediately impressed Ed—not least because the tall, thin, and resourceful Kentuckian, son of a Leatherneck general, was, in Whitcomb’s words, “dead serious about escaping.”

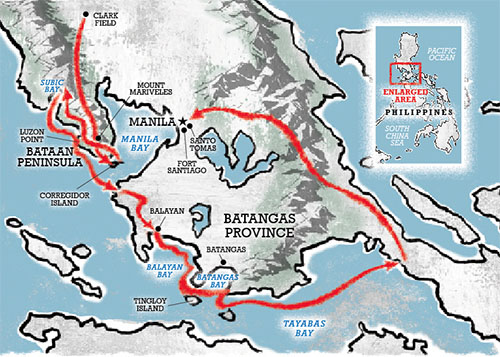

Across Manila Bay they could see the shore of Cavite, eight miles to the south. Swimming there was impossible, but if they could somehow reach Corregidor’s north shore, they might be able to swim back to Bataan. They figured they could then continue north, traversing the jungle around Mount Mariveles’s flanks en route to Subic Bay, northwest of the Bataan Peninsula. There they would commandeer a boat and sail for China, more than 600 miles north.

It was an audacious plan, but the two immediately started preparing. Over the next days, Ed and Bill built endurance by swimming in Manila Bay for as far and as long as suspicious guards permitted. Meanwhile, deaths in camp were rising. The two agreed to “make a move,” Whitcomb said, “while we still had the strength to do it.”

Desperation and opportunity converged on May 22 during an afternoon wood-gathering detail. Outside camp, Bill and Ed dropped unnoticed into a deep foxhole where they huddled, scarcely daring to breathe, until the work party departed. Then they set out for the north shore and, at sunset, began swimming, guided by a light on Bataan’s distant shore.

The two made good progress—or so it seemed until the waters grew choppy. It drizzled, then rained so hard it became impossible to see or communicate. Ed was convinced their battle for survival had been lost.

Once the rain stopped and the waves subsided, Ed and Bill somehow managed to find each other. “But we had no sense of direction,” Ed recalled. They treaded water until their destination light came back into view. It seemed much closer than before, so the men swam “with new enthusiasm” toward a gut-wrenching discovery: the light was on a ship tied up at Corregidor’s north dock. They had been in the water two hours and were no more than a quarter mile from where they had started.

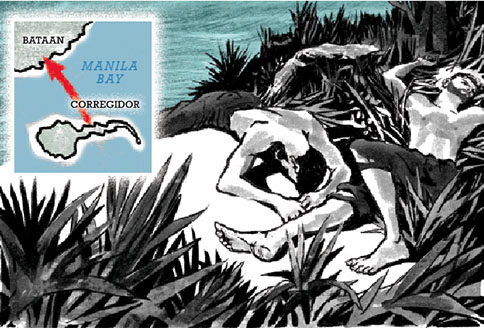

With little choice, Ed and Bill again turned north, this time stroking mechanically, “like walking, hour after hour,” Ed said. “We did not swim hard or fast but we kept a steady gait.” Near dawn they reached Bataan’s shoreline. “We dragged ourselves into a clump of bushes and collapsed, wet and exhausted.” They slept all day, and awoke with the sun low in the western sky.

AS BEFORE, THIS ESCAPE—Ed’s second—had come none too soon. Within days, the Japanese herded Corregidor’s POWs into cargo vessels for transport across Manila Bay, then force-marched the captives more than five miles through Manila to Bilibid, a stone-walled prison turned POW camp.

Ed and Bill, meanwhile, began an exhausting roundabout expedition by foot and boat. Ed quickly learned that getting out of prison camp had been the easy part: “We had to cope with jungle, starvation, malaria, treacherous natives and the Japanese.”

To avoid Japanese soldiers, the pair tried negotiating Mount Mariveles’s steep jungle trails, only to find the going too exhausting. Risking the coastal road instead, they discovered a cache of clothes and weapons, but no food. When they chanced upon a thin, old horse, Bill, momentarily heedless of the Japanese, shot the animal. They carved it up, carrying the parts to a clearing by a stream. But as Ed and Bill struggled to kindle a fire, shots rang out. They dropped everything and ran, sheltering in the depths of the jungle. The two waited hours before trudging on, eventually finding a cashew tree ripe with fruit.

Trekking in cautious stages, occasionally succored by friendly Filipinos, Ed and Bill reached Subic Bay a week later—only to find the Japanese had confiscated or destroyed all ocean-going vessels. China looked out of reach. Sheltered in a fisherman’s hut, Ed and Bill recuperated as they plotted a new course: island-hopping south to Australia.

Paying 30 Philippine pesos for their host’s coastal outrigger—a banca—Ed and Bill sailed out of Subic at night, planning to steer island-to-island until they found a craft sturdy enough to reach Australia. In three nights of sailing and rowing, the banca carried them south along Bataan’s western shore to Luzon Point. It was now June 8—just 17 days after they had escaped from Corregidor—and once again their toil had landed them within sight of their departure point.

As darkness fell, they edged their outrigger into the water to begin the 18-mile leg across the mouth of Manila Bay. Blessed with a tail wind, the craft, Ed recalled, swept past “the black outline of old Corregidor [on] a fast ride across the channel.” Hard going, though, lay on the far side. The banca started taking on water; Ed and Bill unfurled the sail, bailed furiously, and made for shore on southern Luzon. A small cove eventually afforded shelter, but high seas left them stranded. After several days, with provisions depleted and waves seeming to subside, they tried again. They scarcely got underway before a big roller snapped their outrigger and heaved them on the rocks.

So Ed and Bill again set out on foot, this time south into Luzon’s Batangas Province, the domain of Sixto López, a fierce patriot for Philippine independence and scion of a wealthy family. Though they never met the elderly padrone, the pair, shepherded and sheltered by López’s minions, became his guests. Riding donkeys, they traveled to a remote plantation, where they encountered two more Rock escapees, both U.S. Marines: Reid C. Chamberlain and Private First Class Tremel O. Armstrong.

López’s hospitality was welcome—but seductive. Reid and Tremel had already lolled about the López plantation for a month, reluctant to leave. Even when Ed’s and Bill’s Australia plans shook Reid’s and Tremel’s nonchalance, it wasn’t until late July that the quartet finally cast off from the coastal town of Balayan aboard a 24-foot outrigger López had amply provisioned.

Their coast-hugging itinerary had them following Balayan Bay’s eastern shoreline south to Tingloy Island, then turning east across Batangas Bay bound for Tayabas Bay. It was slow going. Seven nights of feeble winds carried Ed, Bill, Reid, and Tremel scarcely 25 miles. Daytime winds were stronger—but Ed argued that daytime travel was too risky. His companions disagreed. The next day, Bill, Reid, and Tremel cast off from Batangas Bay’s eastern shore, tacking east in broad daylight toward Tayabas Bay.

Ed was stranded—but not for long. Within a few days he encountered two American mining engineers, Ralph Conrad and Frank Bacon, provisioning their own Australia-bound outrigger. The three joined forces. Under “a good northwest wind…we decided to sail directly across Tayabas Bay,” Ed said. “After sailing until dawn, the wind was still good, and there seemed little chance of being caught by the Japs. About eleven o’clock we finally pulled up on shore.”

Local villagers greeted them, as they often had before. This time, though, something felt different. The people stood around silently and unwelcomingly; Ed sensed something was wrong. Indeed, as he rested in a village hut, Ed looked out to see Ralph and Frank “surrounded by a dozen Filipinos with drawn pistols.” This latest set of hosts, sympathetic to the Japanese, confined the men to a municipal jail. On August 14, Japanese authorities transported the trio to Manila’s Fort Santiago, a notorious dungeon dating to Spanish colonial times.

THREE WEEKS LATER, Ed emerged battered but unbroken from Fort Santiago—his third escape. Shelley Smith Mydans, a writer and wife of Life magazine photographer Carl Mydans, described Ed’s arrival at Manila’s Santo Tomas University, where the journalist couple—along with 3,500 American, British, and Dutch civilian internees, men, women, and children—had been imprisoned for the duration. “He was very dirty and ragged, his tan trousers in shreds over his knees,” Mydans wrote of a character inspired by Ed in The Open City, her novel of wartime Manila. “He was heavily bearded…and grinning like a fool.”

Shelley and Carl Mydans had already covered the war from Europe to China when, in October 1941, they traveled from Chungking to Manila to report on Philippine defenses. When the city fell in January, Japanese soldiers delivered Caucasian expatriates to what Carl called “a great dusty compound” ringed by “concrete wall…stretches of barbed wire…and iron picket-fence.” In transiting across town to Santo Tomas, Ed had again dodged a worse fate: at Fort Santiago 600 American POWs would eventually die of suffocation or hunger in its stifling confines.

Ed owed his escape from Fort Santiago to memory and persistence. Certain that revealing his identity as an American airman would mean death, Ed adopted a cover suggested by Ralph Conrad and Frank Bacon. The two knew a Baguio mine superintendent named Fred Johnson who had left the Philippines just before war began. Fred was middle-aged, but Ed could pretend to be Robert Fred Johnson, the man’s son.

Caged apart from Ralph and Frank, Ed endured daily interrogations interrupted only by near-death bouts of malaria. His interrogator probed for inconsistencies in the Robert Fred Johnson backstory. It was cat-and-mouse, seasoned with psychological and physical torture. A passage in The Open City best captures the final session with the Japanese tormentor: “He got himself into a very bad mood…He stood there and then he drew his sword with both his hands and hit me across the back with the flat of it…I was numb while he kept on hitting me. I thought my back was broken. I asked him to please shoot me but not beat me to death.”

Instead, guards dragged Ed back to his cage; several days later the presumed civilian was transferred to Santo Tomas. Having “passed the most important test of my life,” as Ed put it, he had reason to grin.

BUT SANTO TOMAS, though for now a welcome haven, was also a potential trap. “Internees wore clean clothes and ate at tables—luxuries I had not enjoyed for months,” Ed observed. But he knew his masquerade was fragile. Some of his fellow internees, aside from Ralph and Frank, were from Baguio and knew he had nothing to do with mines.

Ed needed a fourth escape. Surprisingly, a few days later, a gambit opened. The camp commandant unexpectedly announced he would send 130 prisoners to Shanghai. But the commandant had trouble filling his quota: as Carl Mydans recalled, “a psychosis had crept through Santo Tomas like a fog, darkening everything outside the fence…Now it was unthinkable to venture out across the sea…The more he urged his prisoners to leave, the more they suspected a trick.”

Aware any additional scrutiny could blow his cover, Ed nonetheless applied for transfer. The Mydanses did as well. Remarkably, within 10 days they were on their way, first by bus to the port, then by freighter—the Maya Maru—bound for Shanghai.

At first, much like Sixto López’s remote plantation, Shanghai seemed idyllic. After they arrived in mid-September, the Mydanses arranged clothes, money, and even accommodations for Ed—at Shanghai’s Palace Hotel. There were horse races, new friends, and parties. And when a bout of malaria felled Ed, an American missionary physician, Hyla S. Watters, was there to pull him through.

Though still determined to escape, Ed could see a major hurdle: Nationalist Chinese forces were headquartered in distant Chung-king, about a thousand miles away. And, Ed learned, six U.S. Marines attempting to escape Shanghai had been tossed into the city’s version of Fort Santiago. Knowing that leaving Shanghai for a solo journey across vast stretches of Japanese-controlled territory was beyond even his ability, he felt trapped.

That sense increased when the Japanese clamped down on the free-wheeling city. At the close of 1942 came word that all Allied citizens faced internment. In February 1943 Ed, Carl, and Shelley were among hundreds herded into Chapei Internment Camp, one of seven civilian confinement sites in and around Shanghai.

Over the next dolorous months, as circumstances for internees throughout the Pacific worsened, a new escape channel took shape. Early in the war, neutral intermediaries—Sweden for the Allies, Portugal for the Japanese—had arranged a person-for-person exchange of several thousand Allied and Japanese internees, including diplomats. Now a second exchange was in the offing.

Lacking a passport, Ed figured he would be among the last to go. “Robert Fred Johnson” had only a Swiss-issued photo ID card that Ed had acquired in Shanghai. But then Carl Mydans learned the U.S. State Department was pressing for the release of American civilians who had been originally interned in the Philippines. After more anxious days, “Robert Fred Johnson” joined the exchange roster.

Ed was jubilant: “I was going home.”

THE REPATRIATION—Ed’s fifth escape—began on September 20, 1943, when selected Shanghai internees, among them Carl and Shelley Mydans and “Robert Fred Johnson,” boarded the Teia Maru, a commandeered French passenger liner. Ahead lay internee retrieval stops in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Saigon, and Singapore; then transit through the Indian Ocean to Goa, a Portuguese colony at the time, on India’s west coast. There, in a formal exchange in mid-October, the Teia Maru’s passengers simultaneously switched ships with Japanese passengers arriving aboard the Swedish liner Gripsholm.

The Gripsholm voyage from Goa to New York—with stops in South Africa and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—finally freed Ed from Japanese control, only to substitute new uncertainties. Did he face consequences for imposture or desertion?

An answer began to emerge on November 3, 1943, when Lieutenant Colonel George D. Dorroh of the U.S. Army’s Central Intelligence Group received secret orders from Major General George V. Strong, assistant chief of staff for army intelligence. “You will proceed to Rio de Janeiro and board the GRIPSHOLM…You will effect a complete identification of Edward (sic) Doud Whitcomb as a member of the armed forces…. You will instruct…Whitcomb that he is not…to discuss any phases of his experience with anyone.”

Whitcomb’s daring wartime adventure began at Luzon’s Clark Field, a place he returned to late in the war. In between, his series of escapes took him to China and back home to the U.S. He rejoined the fight in 1945. (Illustration by Chris Serra)

Somehow, through army or State Department channels—perhaps both—authorities had learned of Ed’s plight and were intervening in the final stages of his fifth escape. On December 15, a week after the Gripsholm docked in New York, Colonel Dorroh outlined Ed’s post-arrival disposition in a report to General Strong: “I furnished him with transportation and permitted him to proceed to Washington.”

The authorities’ dilemma: would returning Ed to military duty somehow jeopardize future diplomatic exchanges? After Ed’s debriefing by officers of the Prisoner of War Branch and the Pacific Section, Intelligence Group, Dorroh concluded: “Lieutenant Whitcomb has never, since becoming a prisoner of the Japanese, revealed his true identity. [Accordingly,] “there will be very little chance of him ever being identified as a repatriate aboard the GRIPSHOLM.”

Eventually, Dorroh’s judgment enabled Ed to return to the Pacific. On May 11, 1945, in his first combat flight, Captain Edgar Doud Whitcomb navigated a B-25 bombing-strafing mission from Luzon’s Clark Field to Formosa and back. He had punctuated his five-escape odyssey by circumnavigating World War II. ✯

After returning to combat duty, Ed Whitcomb flew several more missions in the Pacific before taking a staff operations job. Following the war, he began what would become a remarkable career in law and public service. Along the way, he caught up with the fates of the individuals instrumental in his five escapes from the Japanese.

After Reid Chamberlain, Tremel Armstrong, and Bill Harris parted ways with Ed, they acquired a motor boat in an attempt to reach China. When a monsoon swept them back to the Philippines, each joined different guerilla outfits. Armstrong was killed; Chamberlain was smuggled by submarine to Australia and returned to the fighting, only to die on Iwo Jima. Bill Harris, meanwhile, was captured and imprisoned in Japan until war’s end; his ordeal there is featured in Laura Hillenbrand’s book Unbroken. After repatriation, Bill—representing American POWs—witnessed Japan’s surrender on USS Missouri (see “Altar of Peace” ). Tragedy followed: in December 1950 Bill died during the Marines’ epic retreat from Korea’s Chosin Reservoir.

Mining engineers Ralph Conrad and Frank Bacon—like thousands of other Santo Tomas internees excluded from the Gripsholm’s exchange roster—were liberated in 1945 when GIs stormed Manila. Fellow internee Carl Mydans continued covering global conflicts for Life, while Shelley Mydans wrote more novels. (Ed’s daughter, Shelley Whitcomb, is named for her.)

Ed’s public career pinnacled in 1968 with his election as Indiana’s 43rd governor. Afterward, Ed, then 72, embarked on a 10-year solo sailing odyssey covering most of the globe. Inspiration, says his son John, lay in passages from an anonymous poem: “The clock of life is wound but once… Now is the time you own… Go cruising now my brother… It is later than you think.”

Perhaps so. But it also seems possible that two long years spent escaping from the Japanese drove Ed to keep on the go.

Ed Whitcomb found final haven at a simple riverside cabin in Southern Indiana; he died on February 4, 2016.

—David Sears

This story was originally published in the October 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.