A rare gem of a Civil War memorial can be found in the small coastal town of Eastport, Maine. Patriotic and corps badge murals adorn the walls of a Grand Army of Republic meeting hall there, uncovered when modern construction was stripped away. Although thousands of G.A.R. buildings sprang up around the country after the war—and there were many far grander—Eastport can take pride in that its hall is one of the few that still exists. Countless others, in fact, have been modernized or repurposed beyond recognition, if not razed all together. Also fortunate is that Eastport’s G.A.R. Hall was recently donated to the Tides Institute & Museum of Art, a local powerhouse of preservation already involved in expert conservation of the facility.

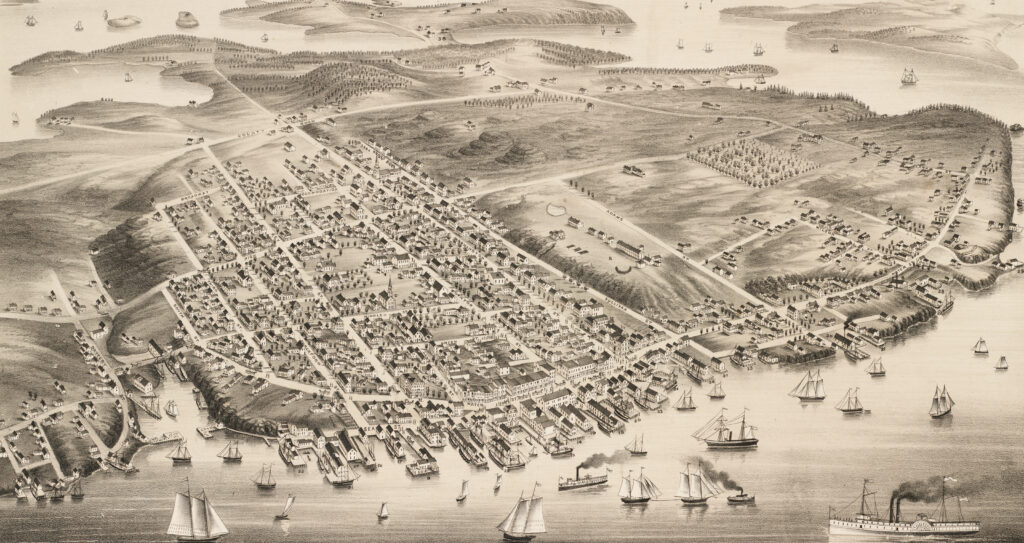

It is no exaggeration to call Eastport “downeast,” for you can go no farther in that direction without leaving the United States and entering Canada. Despite its distance from the centers of the first European settlements on the continent, covetous eyes were eventually cast upon the region’s lush forests, fertile soils, and rich fishing grounds. In 1745, during the struggle between Britain and France for control of what is now Canada, members of a British expedition preparing to lay siege to France’s Fortress Louisbourg took note as they sailed past and later returned to claim the region, wresting it from its original inhabitants, the Passamaquoddy Indians.

The New Englanders, however, were not the only ones who recognized its value. When the British took a worrisome interest in the area in the early 19th century, the fledgling United States built Fort Sullivan on a hill above Eastport’s deep water harbor in 1808. Lest that defensiveness seem unwarranted, during the War of 1812 a British flotilla led by Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy of HMS Victory fame took possession of the town. It was held in what Britain was calling New Ireland until 1818, when it was returned to the United States.

When the Civil War tore the country apart roughly a half-century later, it roused men and boys of this far corner of the Union from their homes. Maine, of course, made a remarkable contribution to the Civil War. Despite a relatively small population—just more than 600,000—it sent 31 regiments of infantry, two regiments of cavalry, one regiment of heavy artillery, and seven sharpshooter companies into action, and raised coast guard infantry and artillery units to watch over the state’s line of ports.

Remarkably, 72,945 men between the ages of 18 and 45 (60 percent of the state’s population) would serve, purportedly the largest proportion of any state in the Union. That also meant a high proportion of fatalities: 9,398 (3,184 killed or mortally wounded in battle, twice that number from disease). Although the 1860 population of Eastport was a mere 3,850, the little town sent 614 men to serve in the Army and Navy, leaving scarcely a Maine regiment without an Eastport man in its ranks.

Those lucky enough to return home after the war soon came to accept that those with whom they served best understood the terrific impact their wartime experiences had had on their lives. Many served with men from their hometowns, where what kept a man going was the desire to not let down his brother, his cousin, or his best friend. But there were also relationships forged in moments as disparate as those of mortal danger, or those hours of paralyzing boredom, loneliness, and homesickness.

For many veterans, the answer was the Grand Army of the Republic, and though Maine’s population was small, by 1868 the state saw more than 167 G.A.R. posts in towns across the state, with more to follow. The posts served many of the veterans’ needs including ones beyond camaraderie. There were bereaved families, and those whose loved ones had returned disabled, who needed financial assistance and support.

It was also important that those who never returned would be remembered and honored. Eastport’s Post #40 hoped to memorialize Captain Thomas Roach of the 6th Maine Infantry, who had been mortally wounded during Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s Second Fredericksburg assault on May 3, 1863, during the Battle of Chancellorsville. Roach had his wounded leg amputated below the knee and would die several weeks later after gangrene set in.

The Eastport veterans initially committed to naming their post in Roach’s honor, but it eventually became known as the Meade Post in honor of Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, who in 1869 had been instrumental in stymieing plans to use Eastport as a staging area for a possible attack by the Fenian Brotherhood on British interests in the Canadian province of New Brunswick. The Fenians hoped that in posing an armed threat against New Brunswick, British naval vessels would be forced to remain engaged in nearby waters and would be unable to recross the Atlantic Ocean to defend against an armed insurrection in Ireland.

After a ship loaded with weapons and ammunition for the Fenians arrived in Eastport’s harbor in April 1869, Meade, on behalf of the U.S. government, quickly seized the ship’s cargo and effectively put an end to the threat.

Not all memories were grim for Eastport veterans, as Maine soldiers acquired a reputation for valuable skills other than their tenacity in battle. The number of lumberjacks in the 6th Maine, for instance, made them a handy addition to any army. Their proud commander decreed to one visiting general, astonished as a work party hewed trees in the Eastern Theater, that the 6th Maine was “axing” its way to Richmond.

The Maine boys were also known for their adept foraging skills. When asked how far Union troops had advanced toward the enemy, their division commander at the time, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, responded: “That’s uncertain; but if you want to know, go out and pass the picket line and go as much farther to the front as you think it safe to do; then climb the tallest tree you can find, and off in the distance you will still see men from the Sixth Maine in the corn field stealing corn.”

Since many an Eastporter made his living on the sea, plenty chose to serve in the U.S. Navy during the war. They served on more than 200 ships, most enduring the tedium aboard vessels assigned to blockade duty, but a number volunteered for the naval shore parties that assisted in the capture of North Carolina’s Fort Fisher in January 1865. Two Eastport men, Edward Bowman and Clement Dees, received Medals of Honor for their Fort Fisher contributions.

Dees, unfortunately, forfeited his medal by going AWOL after the war, but the Navy saw to it that another participant in the Fort Fisher assault, Joseph Cony, was not forgotten—naming the destroyer USS Cony, built in August 1942 at Maine’s Bath Iron Works, in his honor.

Yet another Eastport sailor whose Civil War service was anything but routine was Eastport’s Captain John Crosby, acting commander of USS Housatonic—the first ship sunk by a submarine in warfare. In a night attack by the Confederate vessel H.L. Hunley, Crosby first believed the long, thin shadow in the water was a log, but as it continued to approach his ship ordered the crew to quarters, the ship’s chains slipped, and its engine backed, although it would be too late. Hunley’s spar torpedo struck Housatonic amidships near its magazine, and the resulting explosion sealed its fate. Hunley’s eight-man crew, however, paid for their heroics with their lives.

The restoration of the Meade Post #40 G.A.R. Hall is an outstanding memorial to the Eastport veteran soldiers and sailors, always lionized by the town’s residents, but particularly so in their later years—usually finding a prominent place in the annual July 4 parade. Two of Eastport’s last surviving Civil War veterans were Peter Kane, who rode and fought in the 1st Maine Cavalry, and Fred Call, who served in the 7th Maine Infantry as a teenager. All five Call family boys—William, John, Stephen, Levi, and Fred—served in the Union Army, with all, by great fortune, surviving.

Fred and Peter made the trek to Gettysburg for the milestone 50th anniversary, and on their return, the hometown newspaper reported, “The Gettysburg veterans are home again, coming back with weary feet and tired body but filled to the brim with delightful memories, not only of scenes of half a century ago renewed, but with the realization of the unitedness of this great nation….”

That a historic structure such as Eastport’s G.A.R. hall has survived, and its importance recognized, is gratifying for many.

Diane Smith, an author of several military histories (dianemonroesmith.com), writes from Holden, Me. She thanks Tides Institute’s Hugh French and her husband, Ned, for their help.