Traveling safely underwater in an enclosed airtight capsule had been a dream of man for millennia. Although various plans and designs for a watercraft capable of accomplishing this were being drawn as early as the 1500s, reportedly the first actual prototypical submarine—a crude, oar-powered rowboat-like affair—was built in 17th-century England. Once the possibility of beneath-the-waves travel seemed feasible, man’s thoughts turned to its application in war. The goal became the creation of a manned stealth weapon that could glide undetected beneath the waves and deliver a killing blow to an enemy vessel.

In America, the first use of a subaquatic vessel in wartime occurred in 1776, during the Revolution. The craft, a one-man wooden structure dubbed Turtle, made several unsuccessful attempts to sink British vessels, and was subsequently retired. During the Civil War nearly a century later, both sides strove to develop an undersea technology capable of crippling the other’s warships. Although the Rebel sub Hunley has received the lion’s share of recognition—and did indeed manage to sink a Yankee sloop-of-war, albeit at the cost of the vessel and its crew—there were several other underwater naval vessels active during the four years of conflict.

Interestingly, many people at the time viewed submarine warfare as a terrorist activity. In fact, Southern submarine technology—which far outstripped that of the North—was overseen, not by the Confederate Navy Department, but by the CSA Secret Service. Sabotage played a large part in the South’s military strategy throughout the war, and the underwater vessels that the Northern papers were referring to as “infernal machines” were seen as one more dirty tool on the Confederate belt.

Credit for the first dedicated effort in submarine warfare almost certainly goes to the South. In the summer of 1861, underwater explosives engineer William Cheeney devised a two-man craft (Hunley required eight crew members) that took in air through a tube held on the surface by a large flotation collar. During a September trial, it submerged in the James River and moved steadily toward a target barge. When it neared the barge, a diver left the vessel and—breathing air through a hose connected to the sub—attached a charge of explosives to the barge. Backing away from its target, the sub triggered the charge, literally blowing the vessel out of the water.

The test was an unqualified success, with one exception: A Union spy—one Mrs. E.H. Baker—had witnessed the episode. After subsequently touring a local iron works, Baker also determined that another such vessel was being fabricated. She promptly reported her findings to Washington, whereupon the Union Navy Authority ordered protective anti-submarine nets to be placed around all Northern ships at Hampton Roads, Va.

Ironically, Cheeney’s tests went much smoother than the nameless sub’s performance in action. On its first attempt on a Yankee ship, the sub became entangled in the netting, escaping only with difficulty. During a second attempt weeks later, Yankee pickets spotted its floating collar and cut the air hose. What happened to the vessel and its crew from there is unknown.

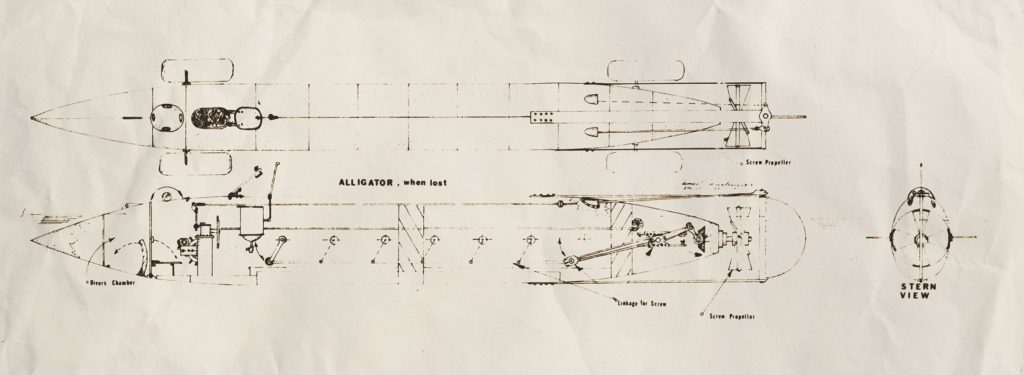

Ironically, the North could have launched its own highly effective submarine months ahead of Cheeney’s endeavor, were it not for institutional ignorance, arrogance, and incompetence. A recently immigrated Frenchman named Brutus de Villeroi brought with him to America what he called his “Sub-Marine Propeller,” a highly sophisticated vessel that he dramatically introduced to the Union forces in mid-May 1861 by surfacing unannounced off the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Its interest piqued, the Navy commissioned him to oversee the construction of a larger version, but de Villeroi proved unbearable and the Navy inflexible, which led to his removal from the project.

When the 47-foot Alligator, as it was dubbed, was finally completed a year later, the naval authorities sent it up Appomattox Creek to destroy a railroad bridge—the antithesis of what it was designed for! Predictably, the operation failed, in part because of shallow water. In early 1863, Admiral Samuel F. DuPont ordered Alligator to Charleston, with orders to clear the harbor of mines. While it was being towed around Cape Hatteras, a furious storm arose, and Alligator, taking on water at the ends of its towlines, wallowed in the swells. When one of its two towlines separated, Alligator was cut loose, whereupon the most sophisticated and ill-used submarine of the war went down.

Alligator did not represent the North’s only effort, halfhearted though it was, to introduce underwater technology into the war effort. During the summer of 1863, 41-year-old New Jersey engineer Scovel Merriam contacted Rear Admiral John Dahlgren regarding his invention. Merriam and his partner, Woodruff Barnes, were offering the Union Navy their bulbous, iron-plated underwater vessel—dubbed the Intelligent Whale—for the triple purpose of clearing Charleston Harbor of such objects as pilings, sunken vessels, and mines, capturing or severing Rebel lines of communication, and sinking enemy ships. If successful, Merriam stipulated that he would be paid the staggering sum of $250,000—well in excess of $8 million today.

Shortly after reviewing the proposal, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles authorized Merriam to build his vessel for the purpose of clearing out Charleston Harbor.In early August 1864—six months after Hunley sank USS Housatonic—Merriam performed a test of the newly constructed submarine before a small panel of Union naval officers.

Apparently the sub was nowhere near ready for testing. The review was damning, pointing out, among other things, that “no attempt was made to navigate the vessel when submerged….In our opinion the vessel can only be used as a self-propelling diving bell, to make submarine explorations and preparations for removing obstructions in comparatively smooth and peaceful waters.”

Welles promptly rejected Merriam’s proposal, whereupon the inventor, after actually finishing his submarine, offered it for demonstrations before the general public. Many of the vessel’s features—including the ability to send forth a diver from inside the sub without admitting water—were, in fact, remarkable. Reviews were generally favorable. Oliver Halsted, a prominent lobbyist and close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, immediately bought shares in Merriam’s company, and shortly thereafter, bought the boat itself.

In early 1865, Halsted convinced both Lincoln and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant of the efficacy of employing his vessel for the uses specified by Merriam—by which time the war was all but over. The U.S. Navy purchased Whale in 1866 and subjected it to several tests over the next decades before putting it on display at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Today, the Intelligent Whale—the submarine that never went to war—can be viewed at the National Guard Militia Museum in Sea Girt, N.J.

In October 1864, the Confederates launched an attack on the wooden-hulled broadside ironclad USS New Ironsides. Their weapon was a small cigar-shaped, multi-plated, steam-powered vessel christened David. Technically, it was a “semi-sub,” since it could not completely submerge without dousing its fires. It could, however, travel nearly undetected, showing only its upper shell.For the attack, David utilized a “spar torpedo”—a heavy charge mounted at the end of a long spar protruding from the vessel’s bow. The strategy was to plant the charge in the side of the enemy vessel and hope for the best. The “Goliath” that this David faced would prove impervious to the assault.

Lewis H. West, a young seaman aboard New Ironsides, wrote about the attack in a letter to his mother:

“A short time after 9 P.M, just as I was turning in, the officer of the deck hailed something. The hail was followed by two or three musket shots and a tremendous crash and explosion, that sounded as if the ship’s timbers were all smashed in. The drum beat to quarters, and as I had not yet been stationed, I [went] on deck to see what was up. The marines were keeping up a heavy fire of musketry on some small object in the water, that in the darkness looked as much like a barrel as anything else. In a few minutes it drifted out of sight or sunk. Many tons [of] water were thrown on deck by the explosion, but on examination the ship was not injured in the least, beyond having a few storeroom bulk heads demolished…”

Injuries to the crew were minimal. One man suffered a broken leg, while another, as West reported, was “shot through the body, by a musket fired from the nondescript craft, just as he fired at it.” The tremendous surge of water from the explosion flooded the sub’s smokestack, “putting his fires out and entirely destroying his motive power….Finding they could not get away they all (five in number) jumped overboard to avoid the musketry which we were pelting them with. The other three are supposed to be shot or drowned, and the machine sunk.”

Actually, two members of David’s crew were pulled from the water by Yankee vessels, and David’s assistant engineer somehow maneuvered it back to port. It would engage in two more actions in 1865, attacking the screw steamers Wabash and Memphis—also unsuccessfully.

At least 20 submarines were active during the war, most belonging to the South (five alone outside Shreveport, La., all sunk late in the war to prevent their capture). While the Union generally attempted to use them to remove underwater obstacles, the South doggedly went after Yankee shipping in an attempt to break the blockade of its coastlines. All the same, the damage inflicted by submarines from 1861 to 1865 was minimal.

Heading beneath the surface in these largely untested metal-plated vessels required unimaginable courage. The dangers were many, both from the enemy and from the quirks of the vessels themselves. Hunley was the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in time of war, yet the Rebel sub itself sank three times, killing 21 men, including its inventor. Nevertheless, once opened, the door to subsurface warfare would remain so.

Improvements made over the past century and a half are staggering. Whereas Hunley was powered entirely by muscle, modern-day submarines are driven by nuclear reactors. Hunley offered only around two hours of breathable air, provided the circulation system was functioning; today, a nuclear-powered sub can remain submerged virtually indefinitely. In the days of the spar torpedo, operational success relied on the ability to surreptitiously attach a charge directly to the enemy vessel’s hull; modern subs can deliver an accurate, devastating nuclear strike from a distance of thousands of miles. The dream of the ancients—to successfully wage war against the enemy from beneath the sea—has ultimately come to pass.