Just after 3:15 a.m. on May 10, 1968, soldiers in a South Vietnamese militia organization known as a Civilian Irregular Defense Group approached the main gate of the U.S. Special Forces compound at Ngok Tavak. They yelled: “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot! Friendly, friendly.” Gate guards held their fire—a tragic mistake. It was a trap. These CIDG men weren’t friends. They were the enemy.

Forward Operating Base Ngok Tavak, a small outpost in Quang Tin province, 10 miles from the Laotian border, was a satellite of the large Kham Duc Special Forces camp, 4 miles to the northeast. Ngok Tavak was surrounded by rugged mountainous terrain covered with lush, largely uninhabited jungle. Highway 14, nothing more than a footpath and unusable for vehicles, ran past the base to the Laotian border. A small dirt airstrip was in a valley 500 yards north of the base.

Ngok Tavak was an old French Foreign Legion fort on a small ridge surrounded by a double-apron barbed wire fence and an unmarked French minefield. The main position consisted of two rectangular sets of earthen breastworks, one enclosing the other. The outer breastworks measured approximately 55 yards by 70 yards, and the inner about 30 yards by 50 yards, surrounded by a 6- to 8-foot berm with fighting positions built into it. About 20 yards from the fort and parallel to one wall ran a trench about 7 feet deep and almost 10 feet wide. It was crossed by a small wooden footbridge that led to a cleared area the French used as a parade ground.

The forward operating base was commanded by Capt. John White of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam. His force was a mixed bunch, comprising 113 men in the 11th Mobile Strike Force Company, shortened to Mike Force, consisting of militia fighters from the Nung people (an ethnic Chinese minority), along with two Australian warrant officers, three U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers, three South Vietnamese special forces men and three interpreters. There was also a 30-man CIDG platoon, positioned outside the base’s perimeter.

Adding firepower to the base was a 44-man U.S. Marine artillery detachment, Delta Battery, 2nd Battalion, 13th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division. The unit consisted of one officer and 43 enlisted, including a Navy hospital corpsman.

Delta Battery furnished two M101A1 105 mm howitzers, designated Delta X-Ray, to provide artillery support for long-range patrols between Ngok Tavak and the Laotian border. The detachment, commanded by 1st Lt. Robert L. Adams, was airlifted by helicopter to Ngok Tavak on May 4, along with rations, ammunition and a three-quarter-ton truck, similar to a pickup. The two howitzers were in the northeastern portion of the compound behind earthen breastworks 3 to 4 feet high.

The day the detachment arrived was marked by its first casualty. Lance Cpl. Bruce Lindsey was killed while attempting to rig a hand grenade as a booby trap.

“I guess [it was] an omen of the bad things yet to come,” Lance Cpl. Tim Brown said, while Lance Cpl. Greg Rose remembered: “I could ‘feel doom,’ like the grim reaper was close at hand.”

On May 10, as the intruders entered Ngok Tavak, a combined force of about 200 defenders was up against 500 to 600 North Vietnamese Army soldiers. The attackers headed for the .50-caliber machine gun position covering the main approach to the base. It was manned by three Marine lance corporals, Rose, Joseph Cook and Paul Czerwonka, cannoneers from the two-gun 105 mm howitzer detachment.

The enemy assault force started throwing hand grenades and satchel charges, inflicting heavy casualties on the Marines. “A deafening explosion erupted to my right,” recounted Rose, whose colleagues at the machine gun post became casualties as Czerwonka was killed and Cook badly wounded. “I saw a group of the enemy run by with flamethrowers lighting up the perimeter.”

Two companies of the NVA poured through the gap. “When the attack began the NVA came right up the road yelling and firing as if there had been nothing to stop them,” Cpl. Raymond Scuglik recalled. Lance Cpl. Raymond “Butch” Heyne and Pfc. Robert Lopez were killed at the front berm. Pfc. Thomas Blackmon was wounded. Lance Cpl. James Garlitz came across Blackmon as he moved to a firing position. “I tried to help him, and when I was trying he was shot in the head,” Garlitz said. “He was gone, so I had to leave him.”

Simultaneously, the NVA pounded Ngok Tavak with 60 mm mortar fire. The first three rounds hit “boom, boom, boom,” recalled Cpl. Henry Schunck. Pfc. Barry Hempel was killed by one round, which detonated an artillery ammunition storage area and set on fire a three-quarter-ton truck.

The explosion and fire silhouetted the attackers.

The NVA assault scattered the Marine detachment—cannoneers, radio operators, ammunition technicians, a truck driver and a cook—forcing them to fight as infantrymen from one- and two-man positions scattered throughout the base. The NVA attackers were confronted by small arms and machine gun fire from many directions—front, flanks and rear, which confused and disoriented them.

Lance Cpl. David Fuentes, a Mexican American of slight build, had gone to sleep with his shirt and boots off, wearing only a cutoff pair of utility trousers. He found himself totally ignored by NVA soldiers, who mistook him for one of their own. As they rushed past Fuentes to get to the guns, he felt like he was at a turkey shoot. “I was standing there bare-chest with no shoes on and the NVA and whoever else was attacking us, so I was shooting them anywhere I could,” the corporal said. “And when they came in with a satchel to blow up my gun, that really pissed me off. Everything was concentrated to get into the guns, but they were running right by the Mexican.”

Schunck rushed from the protective cover of his position near the command bunker to an abandoned 4.2-inch mortar emplacement at the center of the compound in a more exposed position. Although wounded in the leg, Schunck tried to fire the weapon, but he was suddenly attacked by an enemy soldier with a flamethrower. The Marine shot and killed him. Schunck then left his position to drag a seriously wounded comrade to cover. With another Marine, he moved to an 81 mm mortar, which they fired at advancing NVA troops until they ran out of ammunition. Schunck was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions.

Pfc. Paul Swenarski was sound asleep when the attack began. He grabbed his rifle and took a position along the fort’s wall. “I had two magazine belts and four hand grenades,” he said. “I ended up in a hole in the wall with Cpl. Richard F. Conklin and a .30-caliber machine gun.” The two men kept up a galling fire on the NVA. “We got their attention, and they started throwing grenades and automatic weapons fire at us,” Swenarski added. “We were both hit several times. They fired an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] into our hole and that put us out of business.” Those heroics led to a Navy Cross for Conklin.

Scott “Doc” Thomas, a Navy hospital corpsman, was sleeping when the first explosion erupted. He grabbed his medical kit and started for the artillery command center. “On the way, I ran into two wounded, not too bad as I remember, put battle dressings on them and got up to run,” he said. “Explosions—grenades, mortars, don’t know which—ended up in an open pit that had rice and other stores.” Schunck was there, and Sgt. Glenn Miller, a U.S. Special Forces member, jumped in also. As Miller got up, he was hit in the head and killed instantly. “I remember Schunck holding him,” Thomas said. “Lots of foggy memories after that.”

“Sgt. Miller made me fearless because of his fearless attitude,” Schunck said, “and I think [he] had a lot to do with us making an effective defense. I believe he should have been awarded a Medal of Honor.”

Garlitz was asleep next to his howitzer when the attack started. He ran to his fighting position directly adjacent to the opening in the berm. Almost immediately, “three NVA soldiers came running through the hole in the berm towards my gun,” he recalled. “The first one I shot in the side of the head. It was quite obvious that I had killed him.”

Somewhat shocked to have killed someone, Garlitz didn’t have time to dwell on it. The dead man’s two buddies knew “where I was at, so their attention was directed at me,” he said. “So, I quickly disposed of them.” Garlitz then noticed a large number of North Vietnamese headed directly for him. “I had a full magazine at that time, and I sprayed it into them, probably two or three bursts,” he said. “I could hear people screaming and moaning.” The NVA targeted his position and blasted it with a recoilless rifle and small-arms fire.

At one point, the Marines had to confront an NVA flamethrower. “Things got pretty hairy for a while,” Garlitz said. “Flames were rolling up over the top of my fighting hole.” Pfc. Charles Reeder said he “saw the flame from a flamethrower set off our ammo bunker. The explosions sent fragments all around, and I felt some burns on my arms, but they were minor.”

Garlitz also got “scorched” but believed he killed the flamethrower’s operator. The corporal pulled back to a position behind a berm in the northeast corner of the base, where he came across six other Marines. “My fellow Marines and me were in such a position that we could still lay down fire towards the opening in the berm,” Garlitz said.

Pfc. Dean Parrett recalled that more NVA fighters came up the road to the Marines’ position. “We killed as many as we could at the time,” he said. “There were dead NVA lying all over the position. What a wake-up call for a bunch of young Marines.”

Parrett found Lopez, the private killed early in the battle, on the berm and saw that he was dead. He noticed one Marine who was shot through both legs and in pain but, “he was happy that he was still alive and earned the Purple Heart.”

Adams, the lieutenant commanding the artillery detachment, had just turned in for the night after checking on his men and “was awakened by the sound of the attacking force,” he said. “I got into my flak jacket I’d been using as a pillow and was immediately hit in the head and back of my shoulder, probably by shrapnel from a mortar.” Staff Sgt. Thomas Schriver, Adams’ platoon sergeant, was badly wounded in the hands and arms by the same round.

Adams momentarily lost consciousness. When he regained his senses, he saw an enemy soldier jump the berm, throw a grenade and run toward the howitzers while spraying fire with a Soviet AK-47 assault rifle. “Two more NVA jump the berm, silhouetted by the burning three-quarter-ton truck.” Adams recalled. “I was able to shoot at them. I could see that the attack was coming through the CIDG position.”

Although severely wounded, the lieutenant was able to reach the bunker where base commander White was coordinating the arrival of a Douglas AC-47 Spooky gunship. About 4:20 a.m. the AC-47, nicknamed “Puff the Magic Dragon,” arrived. White directed the aircraft to fire around the perimeter, particularly the eastern end of the base, which the Nungs had abandoned.

After some soul searching, the captain told Spooky to fire on the 105 mm howitzers because he was concerned that NVA soldiers were in the positions. “There was no alternative but to have Spooky fire on the friendly 105 mm howitzer positions, despite the fact that there may have been friendly wounded in the position,” White said. His request for gunships to hit the howitzers was never acted upon for some reason. (The guns were destroyed by an airstrike after the battle.)

Spooky’s fire was concentrated outside the perimeter. The gunship remained overhead dropping flares and providing a communication link until daylight, when an Air Force pilot flew overhead to determine enemy positions and direct other planes in airstrikes. He called in 30 strikes to keep the NVA at a distance.

Toward dawn, someone yelled, “Tear gas!” The NVA had turned to a new weapon. Reeder, the Marine private, put on his gas mask, “but it was hot, and it felt like I couldn’t see,” he said. “So I tested the air and found the gas was weak and not even close to being as strong as the gas chamber we experienced back in training.”

After the ineffective gas attack, the NVA began a slow withdrawal, leaving the local Viet Cong unit, supported by mortars and recoilless rifles, to contain the defenders.

At first light, the two Australian warrant officers led a counterattack with several Marines and a handful of loyal Nungs. The Marines had decided to go down fighting. White and the remaining survivors “came charging up over the berm and at the same time we charged from where we were,” Garlitz and Rose related in a joint statement. The assault forced the VC to withdraw beyond the perimeter wire.

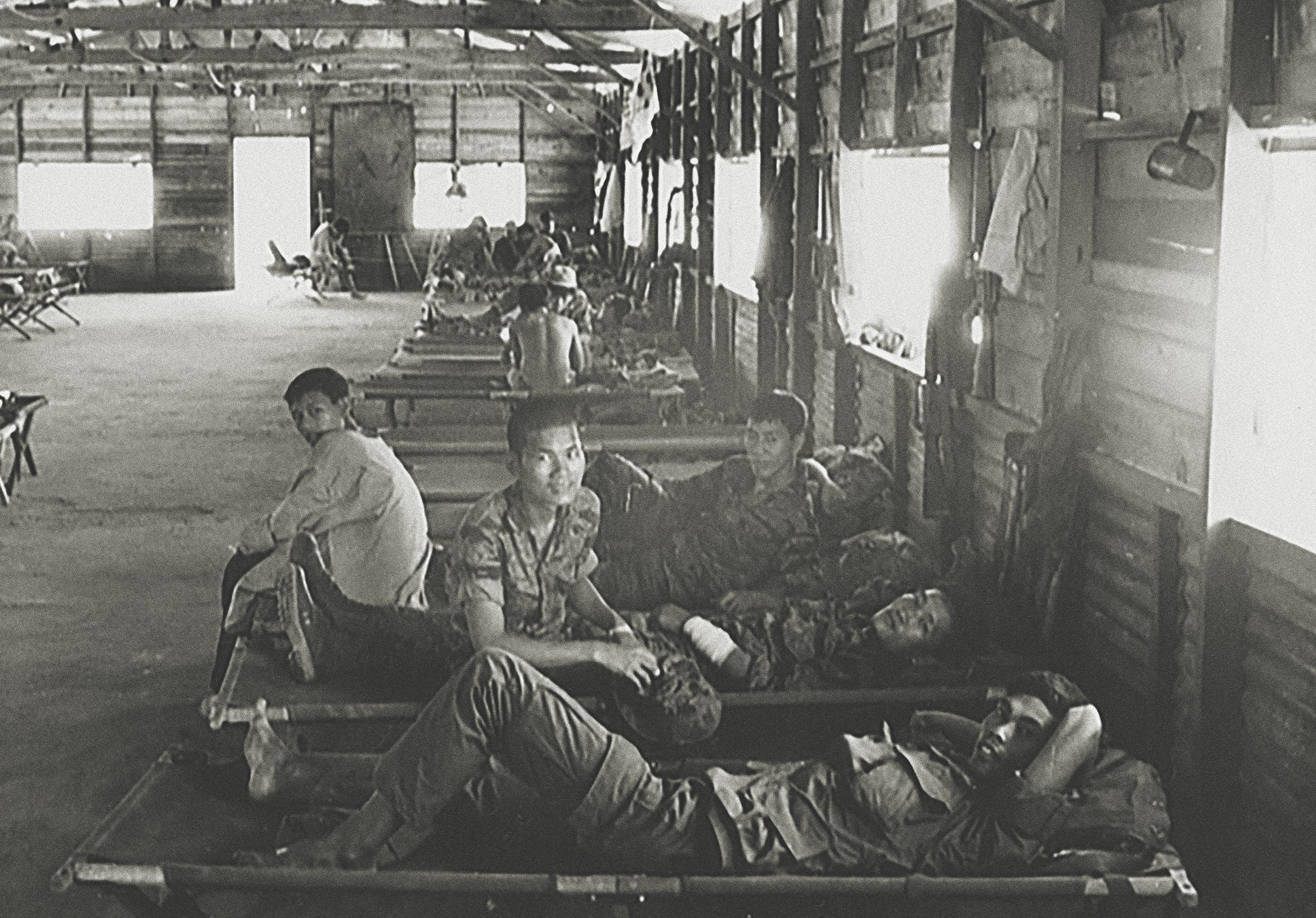

A UH-1H Huey medevac helicopter, call sign Dustoff 55, piloted by Army Maj. Pat Brady, commanding officer of the 54th Medical Detachment, began taking out the wounded under cover of the airstrikes early in the morning. Brady made several trips and hauled 70 wounded men to Kham Duc where an aid station had been set up on the landing apron. Surprisingly, the NVA did not fire on the medevac copter, marked with a large red cross. “We did not take fire even though I could see fire from the surrounding terrain going into Ngok Tavak,” Brady remarked. “Sometimes the disciplined NVA respected the Red Cross, but you could not count on it.”

The NVA did not show the same restraint for reinforcements flown in by two sections of Marine CH-46A Sea Knight transport helicopters from Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron HMM-265. “Our flight of four was doing a radial around the hill while the Army medevac was loading up on the side of the berm,” explained Sgt. Robert Mascharka, one of the crewmen.

The first CH-46 took heavy automatic weapons fire and couldn’t take off after unloading the reinforcements. The second CH-46 dropped off its reinforcements and attempted to pick up the first helicopter’s crew but was hit and exploded, blocking the landing zone. The crew was able to get out, but one man suffered leg burns. A third CH-46A tried to extract the crews of the downed birds but took so many hits that it was driven off and had to make a forced landing at Kham Duc. Despite the damage, the helicopters were able to land 45 replacements. The fourth CH-46A left without unloading any troops.

The next time Brady returned the landing zone was blocked and he had to set the medevac’s front skids on a downed tree just long enough to pick up the stranded aviators. As the Huey lifted out of the zone, two CIDG men and one of the CH-46 pilots, 1st Lt. Horace “Bud” Fleming, grabbed the skids as the Huey flew away under heavy fire.

Fleming and one CIDG man were unable to hold on. They fell to their deaths. A helicopter crewman had tried to grasp Fleming’s hand, but the lieutenant slipped loose. Fleming was listed as missing in action and three years later formally declared killed in action.

White felt that his battered force could not withstand another attack. The base was low on ammunition, and the Mike Force troops were very nervous. Constant U.S. airstrikes all around the position had not silenced the NVA’s sporadic 82 mm mortar fire. At 10:45 a.m., White sought permission to abandon Ngok Tavak but was told to hold on because help was on the way. The commander knew better. The landing zone was blocked with wrecked helicopters. The road was surely ambushed. The base’s airfield was undoubtedly covered by enemy fire. White quietly made the decision to evacuate, despite the orders to remain.

White told his men to haul all the things they couldn’t carry to the command bunker, put them in a pile and rig it for demolition. Extra weapons and equipment were collected, and the two howitzers were disabled by thermite grenades (which contain a chemical mixture that burns at very high temperatures after the pin is pulled and can melt metal).

At 1 p.m., White gave the order to move out. To clear an escape route, he called for napalm strikes down the pathway that had been used for the main NVA attack and then departed with his surviving troops—a mix of South Vietnamese militiamen, the Australians, Special Forces and Marines. Of the 44 Marines at the base, 13 were killed and 20 wounded. Only 11 escaped injury.

The hardest decision was to leave the 13 dead Marines and one Special Forces sergeant behind. There was no way the evacuees could carry the bodies and fight through the NVA positions at the same time. “The American bodies were gathered and put together in the area in the fort behind my bunker,” White said.

White led evacuees along the burning pathway, and they cleared the base without trouble. They descended a hill, crossed a river and climbed a mountainside until they reached a ridgeline where they hacked a landing zone out of bamboo. Four Marine CH-46s came in to pick them up. The helicopters could only carry about 10 at a time, so a shuttle service took the men to Kham Duc, with each aircraft making two trips.

By 6:30 p.m., there were only 20 men left. The pilot of the last CH-46 decided to take them all in one load. He landed his two rear wheels on the ridgeline, holding his front gear off the ground and dumped fuel to lighten the aircraft. He ordered all nonessential items to be thrown overboard. Guns, ammo, helmets, protective vests, radios and even the co-pilot’s helmet were all tossed out. The Marines were taken to Da Nang, where they rejoined their artillery battalion.

The secretary of the Navy presented the Delta X-Ray detachment with a Meritorious Unit Commendation “for extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces during the defense of Ngok Tavak on 10 May 1968.” White received the Australian Distinguished Service Cross in 2019 for his leadership under fire.

All of the men left behind were listed as missing in action, yet they were not forgotten. Brown, the lance corporal who saw an accidental death on May 4 as a bad omen, lobbied the Pentagon to conduct searches of the battlefield. Brown made three trips to Vietnam starting in 1993 to gather evidence in support of excavating the area.

In 1999, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command uncovered enough evidence—bones, dog tags, wallets—to identify 11 of the 13 missing Marines and the Special Forces sergeant. “It took a long time,” Brown said, but “we did what we were trained to do, to make sure our comrades are not left on the battlefield…If it was me left on the hill, I know they would have come for me. I am sorry it took so long, but now we can give them a proper burial in their homeland.”

Five of the remains were returned to their families. The other seven were buried in a collective grave in Arlington National Cemetery. The bodies of pilot Fleming, Green Beret Spc. 4 Thomas Hepburn Perry (missing after the battle) and two Marines haven’t been recovered. V

Dick Camp retired from the Marine Corps in 1988 as a colonel after serving 26 years. He has written 15 books and more than 100 articles in military magazines. Camp lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

This article appeared in the February 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.