It is said that the first automobile race took place the moment the second car was built, but motorsport took a bit longer to appear in aviation. The first air race was flown in 1909, in France, more than five years after the Wright brothers’ first flight. There were four entrants. Two started the race and none finished. The rules had foreseen that. They specified that the winner would be the competitor who had traveled farthest.

Things hadn’t progressed much by August 1927, when the Dole Derby, a heavily promoted race between California and Hawaii, limped to an unfortunate start. Eleven racers entered the contest, six actually flew and two finished. Ten people—pilots, navigators and one unfortunate passenger—died before the race was over. Two entrants later died while searching for survivors.

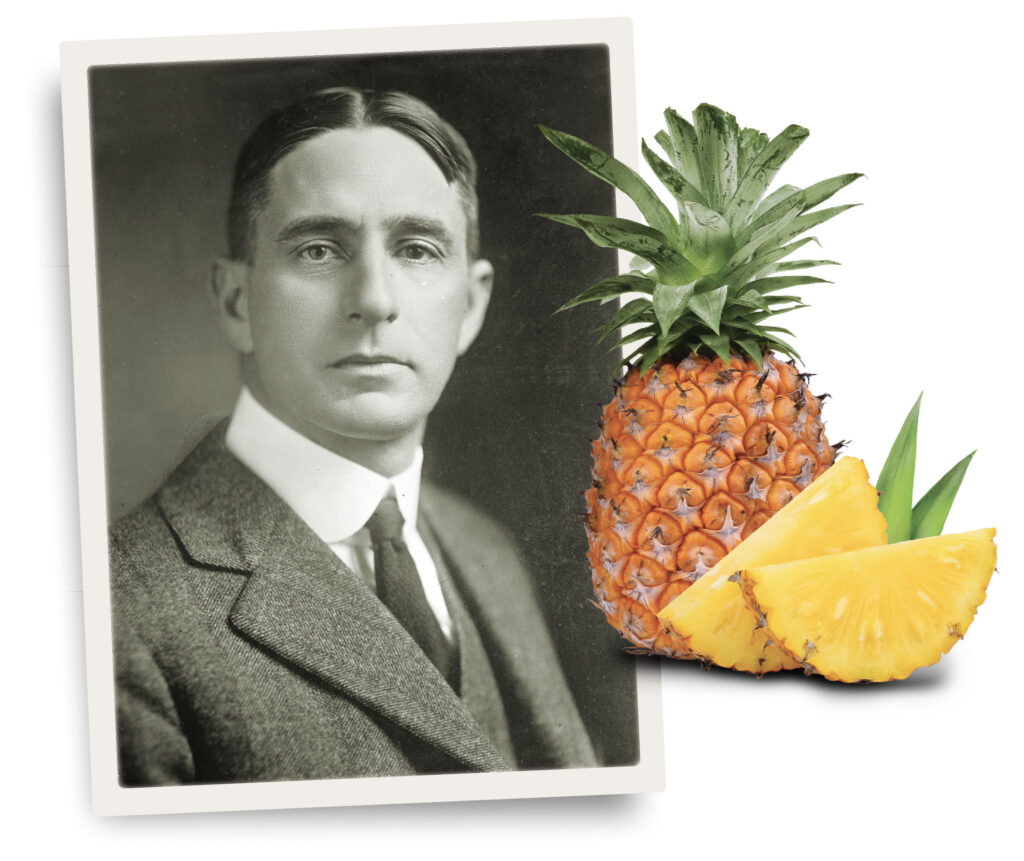

Call it the Dole Disaster and blame it on the pineapple.

In 1899, 22-year-old James Dole moved to Honolulu with a Harvard degree in agriculture in his suitcase, and he began canning pineapple. In 1907, Dole set about advertising his exotic product throughout the U.S. mainland and soon had a hit on his hands. By 1922, Dole pineapples were so popular that young James bought the entire Hawaiian island of Lanai as a 20,000-acre pineapple plantation.

In May 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris, and aviation suddenly became the hottest game in town. Airports and airlines sprang up everywhere; aviators set and broke records weekly. The months after Lindbergh’s flight were called the Summer of Eagles, and some people were seeking a Pacific Eagle. Hollywood theater mogul Sid Grauman offered $30,000 for the first flight from Los Angeles to Tokyo. Dallas stockbroker William Easterwood put up $25,000 for anyone who could make the first flight from Dallas to Hong Kong in less than 300 hours, with no more than three refueling stops. And immediately after James Dole announced plans for what would become the infamous California-to-Hawaii Dole Derby, the San Francisco Citizen’s Flight Committee promised an additional $50,000 prize to extend the route all the way to Australia.

The idea for a Hawaii-bound air race didn’t originate with James Dole. It took a pair of Honolulu newspaper reporters, Riley Allen and Joseph Farrington, to light the fuse. Just two days after Lindbergh’s flight, they sent Dole a telegram—simultaneously printed in the Honolulu Advertiser—pointing out that the post-Lindberghian swoon made the times ripe for someone to offer a substantial prize for a nonstop flight to Hawaii. If Dole ponied up, the reporters said, his reward would be “all the press coverage he could stomach.”

Dole bit. He assumed he would be promoting the first such flight and thus a significant world record. He offered $25,000 and $10,000 (about $426,000 and $170,000 in today’s dollars) for the first- and second-place finishers in a “Derby” in which the only requirement was the aviators had to fly from the continental U.S. to the Territory of Hawaii—no specific takeoff or landing points were named, although Oakland did become the starting point—and that the race would start on August 12, 1927.

Perhaps he should have said the Dole Derby would start the next morning, for two months before the date that Dole set, two Army Air Corps lieutenants in an Atlantic-Fokker C-2 trimotor named Bird of Paradise quietly and professionally flew from Oakland, California, to Honolulu in just under 26 hours. Their airplane was a military version of the Fokker F.VIIa, built in Fokker’s Teterboro, New Jersey, factory. It had been modified for the Hawaii flight—the longest overwater flight ever attempted anywhere—with a larger wing and extra fuel tanks that gave it a range of just over 2,500 miles. Which was cutting it close, since the distance from Oakland to Hawaii was 2,418 miles.

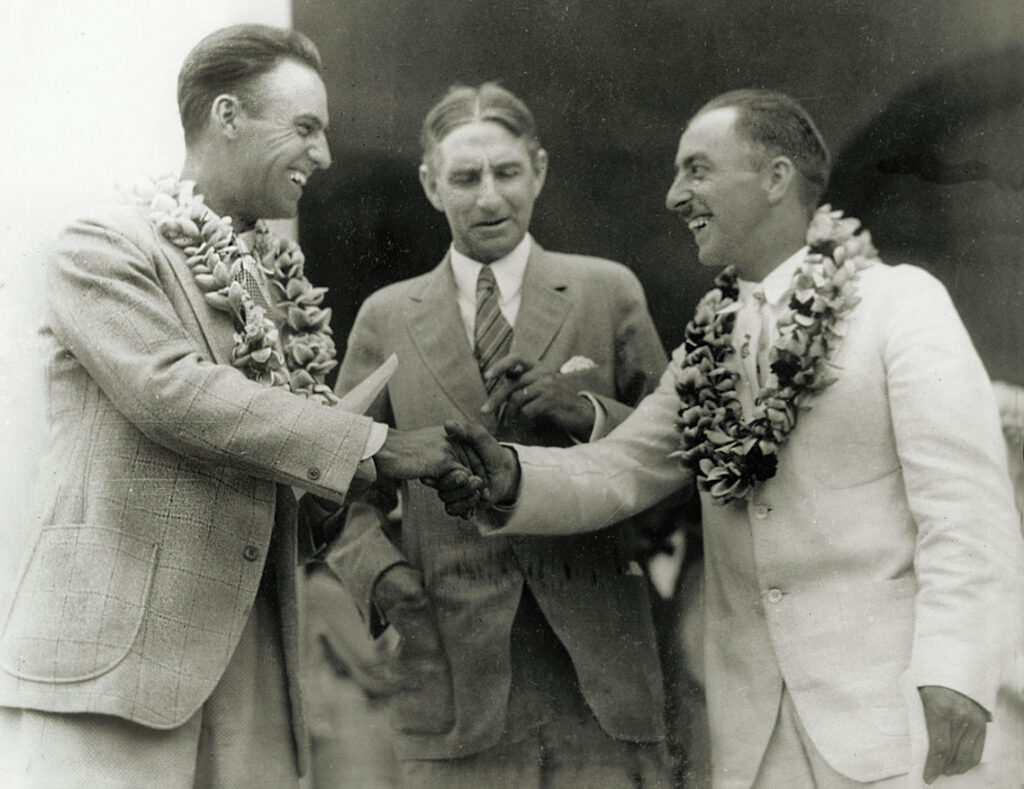

The USAAC had been planning such a trip since 1919. One of the flight crew, MIT-degreed Lieutenant Albert Hegenberger, was a prime mover in the development of long-distance navigation for the Air Corps and had been in charge of developing the service’s radio navigation instruments and equipment. Hegenberger’s pilot was Lester Maitland, an aide to General Billy Mitchell who had spent much of his Air Service and then Air Corps career setting records and winning air races that accrued publicity for the military. He was unofficially the first American pilot to fly faster than 200 mph, and in October 1923 he set an absolute world speed record of just a bit under 245 mph, flying the Curtiss R-6 biplane racer in which he’d finished second in that year’s Pulitzer Trophy race.

Hegenberger’s radio skills turned out to be moot, since the Bird of Paradise’s radio compass and directional receiver both failed soon after takeoff, leaving the crew to rely on a whiskey compass, a drift meter and some celestial navigation to dead reckon their course. Had Hegenberger been more than 3.5 degrees off after 2,400 miles, they would have missed Hawaii. The flight was 900 miles shorter than Lindbergh’s, but all 2,400 miles of it was over water; Lindbergh spent about 2,000 miles feet wet from Newfoundland to Ireland.

Unfortunately, few of the actual Dole Derby contestants were as professional or well-prepared as either Lindbergh or this Army crew.

One dismayed spectator at the Army Fokker’s takeoff was civilian airmail pilot Ernest Smith, who had decided to forego Dole’s prize money by flying the Pacific well before the official race and thus make it irrelevant. But Smith hadn’t planned on the Army making him irrelevant. Smith and his navigator, Charles Carter, took off two hours after the Fokker in their single-engine Travel Air, but a metal wind deflector for the navigator’s observation hatch came loose soon after takeoff. Smith returned to Oakland, where Carter decided he’d had enough and quit. During the two weeks that it took to fix the wind deflector, Smith found another navigator, Emory Bronte, and with his help became the first civilian pilot to cross from the U.S. to Hawaii. They had intended to land at Honolulu but went tanks dry over the leper-colony island of Molokai, 50 miles short of their destination. Smith deadsticked the Travel Air down into a grove of long-thorned mesquite trees, more concerned about his belief that the island was entirely populated by lepers than he was by the forced landing.

Four aviators had successfully made the transpacific flight, and none them had been a Dole Derby contestant.

Their premature accomplishments turned the Derby from a viable attempt to set an important world record into a half-assed dash for money. The racers would, however, still accrue controversial publicity for Hawaii and James Dole at a time when Lindbergh had primed the pump for newspapers to flood the country with news about notable aviation accomplishments. The Dole race also offered the ultimate risk/reward equation: failure meant death. Even though every race plane was required to carry at least a rubber raft, finding floating survivors in the vast Pacific would prove to be fruitless.

To his credit, James Dole was determined that his race would be overseen by professionals who could weed out unqualified crews and ground airplanes that had no chance of success. He enlisted the help of the new aviation branch of the Department of Commerce, which would eventually become the Federal Aviation Administration. Its inspectors demanded that participants have auxiliary fuel tanks that could carry a 15-percent safety margin, and that they carry life rafts and emergency rations, and they added the proviso that nobody could fly without a certified navigator. (One navigator was disqualified after becoming lost during a local flight over Oakland.)

Unfortunately, the Feds did a lousy job of enforcing their requirements.

In the end, 15 pilots paid the $100 fee to enter the Dole Derby. One didn’t even have access to an airplane. Three crashed before they could reach Oakland. One was unable to get qualified before the race. One withdrew before the start. The day before the race, one more entry, an Air King named City of Peoria, was disqualified for not carrying enough fuel to reach Hawaii. “The owner [of the entry] was furious,” read one account of the race, “but the two men recruited to do the actual flight were reportedly relieved.” You have to wonder what kind of pilots would require a regulatory judgment to keep them from taking off on a death trip.

Dole had hoped Lindbergh would enter the Derby, but the stoic Minnesotan wanted nothing to do with the stunt. He realized that putting the compass on E and heading toward a continent—though his own navigation was vastly more precise—was nothing like leaving a continent behind while aiming for a few islands.

The City of Oakland had been considering construction of an airport as early as 1925, and the announcement of the Dole Derby prodded it into action. In just 21 days, Oakland built a 7,020-foot dirt-and-crushed-oyster-shell runway—the longest in the world at the time—and opened the Bay Farm Island airstrip to traffic. It soon became Oakland Municipal Airport (today Oakland International), but it was as Bay Farm Island that it served as the race’s starting point.

Dole Derby fatalities began before the race even started. Navy Lieutenants George Covell and R.S. Waggener died on August 10 when their Tremaine Hummingbird flew into a fogbank and hit a 400-foot-high coastal cliff at Point Loma, soon after takeoff on their way from San Diego to Oakland. The Covell/Waggener entry was Tremaine’s second (and last) design—a large, remarkably ugly, low-wing monoplane with the dihedral of a pool table. Sunk behind a graceless forward fuselage, its cockpit had only side windows and a periscope. One wonders if it would have collided with Point Loma regardless of fog.

One notable thing about the Tremaine was its name: Spirit of John Rodgers. In 1925 Navy pilot John Rodgers had commanded the very first airplane, a twin-engine Naval Aircraft Factory PN-9 biplane flying boat, to make it (in a fashion) from California to Hawaii. Rodgers and his crew ran out of fuel short of their destination and spent nine days yachting toward Hawaii with a sail made from fabric stripped from a wing. Thirsty, hungry and sunburned, they were finally sighted by a submarine and towed to Kauai.

Angel of Los Angeles was next to go. World War I Royal Flying Corps aviator Arthur Rogers died while parachuting from his Bryant M-1 monoplane while testing it near Los Angeles. It would have been one of the most unusual ships to contest the Derby, with a twin-boom tail and a push-pull twin-engine pod between the booms.

Pride of Los Angeles was a twin-engine Catron & Fisk CF-10 triplane that landed short of the broad Bay Farm Island runway while arriving for the race start. The prominent Pride ended up half awash in San Francisco Bay, a particular embarrassment for one of its sponsors, cowboy movie star Hoot Gibson, whose name was writ large on the bright orange fuselage. The three-man crew swam ashore safely. The CF-10 had already earned its share of notoriety thanks to its substantial sandwich of wings, which earned it a derisive nickname, “the Incredible Stack o’ Wheats”—a reference to a popular breakfast meal, a pile of shredded wheat cakes. Gibson was not amused.

Things didn’t go much better once the race actually began. A Travel Air 5000 named Oklahoma, piloted by Bennett Griffin and navigated by Al Henley, had to turn back after a half hour due to mechanical problems. Norman Goddard and Kenneth Hawkins in the “Goddard Special” El Encanto crashed on takeoff. Pabco Pacific Flyer, the only Dole entrant to attempt the race solo, was flown by a former 103rd Aero Squadron pilot, Livingston Irving. His Breese-Wilde 5, designed specifically for the race, flew about a mile and a half before settling into a marsh, terminally overloaded. Irving walked away muddy but unhurt.

Dallas Spirit was flown by another World War I veteran, William “Lonestar Bill” Erwin, who had been credited with eight aerial victories as pilot of two-seater reconnaissance airplanes. His pregnant 20-year-old wife, Constance, was originally scheduled to be his navigator—she was skilled in astronavigation and radio use—but was disqualified for not meeting the age-21 criterion. She was replaced by Alvin Eichwaldt, a former Navy seaman. Dallas Spirit, a Swallow Dole Racer built specifically for the event, was forced to return to Oakland after experiencing engine trouble.

The Lockheed Vega Golden Eagle, flown by Jack Frost with navigator Gordon Scott, was lost at sea, despite having a radio receiver, a variety of safety equipment and flotation gear, thanks to the sponsorship of William Randolph Hearst’s son George and his San Francisco Examiner newspaper. Some optimists said the Vega could float for a month; we’ll never know if it did.

Though Lindbergh shunned the Dole Derby, the race did have its pseudo-Earhart contestant—a 22-year-old fifth-grade teacher from Flint, Michigan, named Mildred Doran. She flew in the Derby as a passenger aboard a Buhl CA-5 Airsedan christened the Miss Doran.

The Buhl was a sesquiplane, a biplane with an atrophied lower wing of less than half the area of the upper wing. Its engine was a reliable nine-cylinder Wright J5 Whirlwind, and the ugly CA-5 had a cabin below and behind an enclosed cockpit. Airsedans would go on to collect an odd bag of distinctions: first airplane to fly a pope (Pius XII); first to make a nonstop round-trip crossing of the continental U.S., using a primitive form of air-to-air refueling; and holder of the record for regularly flying the shortest airline route in the world, across a river in Mexico (the one kilometer flight required two minutes flying time).

The press lost no time in finding Doran more appealing than the male pilots and navigators. She had begun her aviation dalliance under the mentorship of a flamboyant entrepreneur, Bill Malloska, who owned a string of gas stations called Lincoln Oil. Though not a pilot himself, Malloska built an airstrip just outside Flint as publicity for his stations, and Doran became a regular at the field. A flying circus from Nebraska set up shop at the Lincoln Oil runway as their Midwest base and gave $5 rides and put on weekend air shows replete with wing-walking and parachute jumps. Their airplanes all bore the Lincoln Oil logo, and in return they burned free fuel and oil provided by Malloska.

When Doran heard of the cash prizes that James Dole was offering, she urged Malloska to enter the Dole Derby for the publicity assured by making her a passenger. Malloska, ever the entrepreneur, couldn’t resist. He bought the Buhl and turned to two of his air-circus pilots, John August Pedlar and Eyir Sloniger, to decide who would race it to Hawaii. The two pilots flipped a coin to see who got the job and Auggy Pedlar won. He had less than the 200 hours required by the Dole Derby organizers—his function in the Lincoln Oil troupe had been more as wing-walker than pilot—while Sloniger, the putative loser, would go on to become chief pilot of American Airlines and get immortalized in Ernest K. Gann’s memoir Fate Is the Hunter.

Pedlar took off confidently to start his and Mildred’s race, but Miss Doran’s engine started misfiring badly, so he returned to Oakland within minutes. Apparently even young Mildred realized this was the result of more than just an oiled sparkplug. Her fun flight to Hawaii had suddenly turned deadly serious. It took hours of work to fix the Whirlwind’s problems. By this time, Mildred Doran was an unhappy camper, and she re-embarked “looking ashen and in tears,” according to newspaper reporters. Even navigator Vilas Knope urged her to stay behind. But she was back aboard the Buhl when it took off again, the last of the Derby contestants, far behind everybody else. Doran, Pedlar and Knope were never seen again.

Once word arrived that neither the Golden Eagle nor Miss Doran had arrived in Hawaii, Erwin and Eichwaldt, though out of the race, managed to get the Dallas Spirit’s engine running smoothly and took off west to search for the two airplanes. The last thing heard from the Dallas Spirit was a truncated radio call that said the airplane was in a spin about 650 miles west of Oakland.

The race winner was a Travel Air 5000 named Woolaroc flown by Hollywood movie pilot Art Goebel. His navigator was William V. Davis Jr., a pilot himself who was skilled enough to become a member of the Navy’s first official flight demonstration team, the Three Seahawks. Davis went on to become the second Navy pilot to fly faster than sound, in the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket.

Woolaroc was sponsored by Phillips Petroleum, a company that to this day is known for branding its gasoline, and its gas stations, as “Phillips 66.” Though the Phillips airplane’s name hints of aboriginal Australia, it was actually a construct that stood for woods, lakes and rocks, which company founder Frank Phillips felt characterized his ranch outside Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Woolaroc won the race by finishing three hours ahead of Aloha, the only other entrant to finish.

Aloha, another Breese-Wilde, was the sole Hawaiian entrant. The airplane had three 50-gallon wing and fuselage tanks and carried another 250 gallons loose in the cabin, in 50 five-gallon cans. Navigator Paul Schluter, a merchant marine captain, not only needed to navigate but also had to decant five gallons at a time into the fuselage tank. The airplane started the race thanks to the efforts of pilot Martin Jensen’s wife, who at the last minute had raised $15,000 to pay for the airplane. “God bless that darling wife of mine,” Jensen said. “I’ll make it or die in the attempt.” He and Schluter did make it—but they reached Honolulu with only four gallons of fuel remaining, after a variety of navigation problems en route.

One of Dole’s hopes had been that his Derby would engender air travel to Hawaii, and in 1935, Pan American Airways cautiously started service between San Francisco and Hawaii and onward to Manila, operating big four-engine Sikorsky and Martin flying boats. One of the young airline’s major concerns was whether memories of the Dole race would discourage potential passengers. In fact, two PAA directors quit the board rather than be associated with what they feared would become a debacle, since they felt the Dole affair had thoroughly poisoned the Pacific waters.

Though it never did slow airline traffic, the Dole Derby was one of the last major aviation stunts, flown before the pilot community realized that careful preparation, proven equipment and solid skills are more productive than greed, luck and brass balls.