Two years before Charles Lindbergh made his epic solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927, the U.S. Navy was determined to establish a world record for the first nonstop flight from California to Hawaii. Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, was still smarting from the Army Air Service’s successful round-the-world flight the previous year. The Navy’s reputation as an aviation leader—established in 1919 with the first transatlantic flight by an airplane—was at stake, and Moffett wanted to make sure Congressional budget authorizers knew that naval aviators were still pioneers.

Prior to 1925, no Navy aircraft had flown more than 1,200 miles without stopping. In fact, no aircraft had as yet been built that was capable of the 2,400-mile flight from San Francisco to Honolulu. The Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia was commissioned to build a twin-engine, bi-winged flying boat designated the PN-9 to make the first attempt.

A modified version of the PN-8, the metal-hulled seaplane was designed to carry five crewmen and one ton of freight. It boasted twin 475-hp Packard engines, had an upper wingspan of 73 feet and weighed 20,000 pounds fully loaded. The PN-9’s useful load was 10,100 pounds, quite an accomplishment given that few contemporary planes could carry a useful load equal to or greater than their own weight. The PN-9 also had a larger fuel capacity and a wider cruising range than other seaplanes of its day. In other words, the Navy built a credible aircraft to set a new world record.

Two PN-9s would make the attempt, increasing the chances for success. During testing one of the flying boats set an endurance record when it flew nonstop for more than 28 hours, which boded well for the upcoming Pacific flight.

Commander John Rodgers, who came from a long line of distinguished naval officers, was chosen to oversee the record attempt. His great-grandfather Commodore John Rodgers played a key role in the War of 1812, his grandfather Rear Adm. John Rodgers fought in the Civil War and his father Vice Adm. William Rodgers had commanded the Asiatic Fleet. His mother was the granddaughter of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, whose “black ships” had opened Japan to international commerce.

Rodgers himself was a pioneer of early aviation. Among the first group of naval officers to receive flight training, he graduated from the Wright Flying School in 1911, only the second naval officer in history to qualify as an aviator. A highly resourceful pilot, he was also an ace navigator and a bit of a daredevil. In 1911, the same year he received his pilot’s license, Rodgers ascended to 400 feet in a Perkins man-carrying kite (see Man-Carrying Kite from the September 2013 issue). Though that flight lasted only 15 minutes, it demonstrated Rodgers’ fearlessness. Later that same year he took a leave of absence to assist his cousin, Cal Rodgers, in the first successful transcontinental flight across America.

The eyes of the world were on San Pablo Bay, north of San Francisco, on Monday, August 31, 1925, as PN-9s Nos. 1 and 3 prepared to take off. Thousands of well-wishers lined the shoreline, and newspapers ran breathless stories anticipating “the greatest nonstop flight attempted by America.”

Rodgers had selected San Pablo Bay for their takeoff because it was a quiet body of water. Still, Coast Guard cutters were kept busy chasing away curious boaters as the takeoff approached. Meanwhile 10 Navy vessels were stationed at 200-mile intervals between California and Hawaii to provide radio bearings, fuel if needed and a rescue force in the event one of the flying boats was forced down.

After a good luck visit from Admiral Moffett, Rodgers cast off No. 1 from its towboat. It was a few minutes past 2 p.m. when Lieutenant Byron J. Connell, piloting Rodgers’ plane, made his run across the bay. The PN-9 was so heavy, however, that Connell couldn’t get airborne. While he prepared for a second attempt, pilot Lieutenant Allen P. Snody clawed his way into the sky in No. 3.

It took Connell more than four miles to get airborne, but a cheer went up when No. 1 finally lifted off the bay. Army planes from Crissy Field dipped their wings in salute as Rodgers headed for the Golden Gate.

Rodgers’ biggest challenge would be navigation. The Hawaiian Islands were a mere speck in the middle of the Pacific, and there was no guarantee he could find them.

At 5 p.m., just two hours after takeoff, Rodgers reported radio contact with the first Navy ship, the destroyer William Jones. “That was a great relief,” he recalled. “It certainly gave me the assurance that my… methods were all right.”

But shortly after No. 3 flew past William Jones it began experiencing difficulty. A crewman climbed out on the wing to check the port engine and found it was leaking oil. Twenty-five minutes later the oil pressure gauge was at zero, leaving Snody no choice but to make an emergency landing. It wasn’t going to be easy, though. The seas were rough, it was beginning to get dark and they were carrying five tons of gasoline. The force of the landing was so great that the PN-9’s normally square fuel tanks were warped into a cylindrical shape. Nevertheless, Snody managed to put the plane down without mishap.

William Jones didn’t find No. 3’s five man crew until well past midnight. They were taken aboard, and a line was rigged to tow the flying boat to San Francisco. Now all hope for completing the record flight rested with Rodgers and the crew of No. 1.

As Rodgers’ plane pressed on through the night, he had no trouble finding the ships along his path. In fact, the flight was going so well that he radioed Hawaii’s territorial governor to let him know he’d see him the next day. But as the night wore on, Rodgers noticed the port engine’s exhaust flame was burning yellow rather than blue, an indication it wasn’t running efficiently. Gas consumption was averaging six gallons per hour more than during test flights. And the 15- to 20-mph tail winds they’d counted on to drive them across the Pacific were much weaker than expected.

When morning dawned on September 1, Hawaii was eager for news of Rodgers’ progress. At 8 o’clock No. 1 was reportedly within 700 miles of its goal. By noon, crowds began forming in Honolulu to welcome Rodgers and his crew.

By the time No. 1 passed the destroyer Farragut, however, Rodgers was two hours behind schedule. He was 1,600 miles west of San Francisco when he realized he didn’t have enough fuel to reach Hawaii.

“Plane very low on gasoline,” No. 1 radioed. “Doubt ability to reach destination. Keep careful lookout.” According to Rodgers’ calculations, No. 1 had enough fuel to reach the minelayer Aroostook, the second to last ship along his route. Since

Aroostook was a fully equipped airplane tender, he planned to land alongside, refuel and continue on his way. Though he was disappointed by his failure to fly nonstop to Hawaii, at least the PN-9 could then complete the flight. Aroostook sent radio compass bearings indicating it was north of No. 1’s position. Connell followed the bearings, but when he arrived where Aroostook was supposed to be, no ship could be found. It had never occurred to Rodgers that he’d have difficulty finding the one ship he really needed after passing by the others so easily. To make matters worse, rainsqualls made visibility poor. It turned out that Aroostook had sent faulty bearings.

Connell searched for an hour without success. As their fuel supply dwindled, Flight Engineer Skiles N. Pope grabbed a sponge and began soaking up whatever gas he could find in the bilges. Just before their engines cut out, No. 1’s chief radioman, Otis G. Stantz, sent off a partial message: “We will crack up if we have to land in this rough sea without motive power….” After that, there was radio silence.

Headlines in The Honolulu Advertiser screamed “The Flight Is Doomed,” and an extensive search was launched. Since Farragut, Aroostook and the minesweeper Tanager were closest to where Rodgers had presumably gone down, they began scouring the area. But downed aircraft are notoriously difficult to find at sea because they tend to blend in with the water. Submarines, seaplanes and more surface ships soon joined the search, but they found no sign of No. 1 or its crew.

Connell, who’d been in the pilot’s seat for 25 hours, was flying through squalls when No. 1’s engines finally cut out. As he began an unpowered glide from 600 feet, the sea below was roiled by heavy swells. Despite the poor conditions, he managed to safely alight on the water. Rodgers might have been nearly 400 miles short of his destination, but he’d established a new seaplane record by flying nonstop 2,155 miles. More important, everyone was still alive.

Their radio soon proved a source of frustration. The receiving set ran on a battery, so they could hear messages, but their sending radio was powered by a wind-driven generator that only operated while the plane was in the air. In other words, they could hear but not transmit. “It was queer…listening to those hunting for us and being unable to communicate with them,” crewman William H. Bowlin recalled. A message addressed to Commander Rodgers from Aroostook’s captain gave them hope, however: “Cheer up, John, we’ll get you yet.”

On their second day adrift, the five men ran out of cigarettes, so they shared a cigar to keep their cravings at bay. Of more concern was their lack of food and water. They’d already consumed most of their rations. All that remained were 10 ham sandwiches, 10 quarts of water, three pounds of hardtack, six pounds of canned corn beef and assorted scraps. Since the corned beef proved indigestible and they were unable to catch any fish, their food soon ran out.

The real problem was their dwindling supply of drinking water. Before departure, Rodgers had reluctantly accepted the gift of a freshwater still from his mother, but it was useless without fuel to run it. The water from the plane’s radiator was laced with sealant, making it undrinkable.

The first sign of hope came at 8 a.m. that day, when they spotted a commercial steamer five miles away. Waving frantically, they shot off flares and shouted, but the ship passed them by without stopping.

It became increasingly clear they would not be rescued anytime soon. Radio intercepts indicated the search ships were moving away from them. Radioman Stantz had begun cannibalizing engine parts in an attempt to build a rudimentary sending set, but he wasn’t having much success.

At that point Rodgers decided to take fate into his own hands and sail the plane to Hawaii. He knew the area well because he’d served as commander of the naval air station at Pearl Harbor. He also had the necessary navigation equipment, as well as confidence in his own abilities.

The crew stripped fabric from the bottom wing to fashion a sail. Unfortunately, a seaplane doesn’t make a very good sailboat. The best they could manage was to steer a few degrees either side of the wind, using the plane’s tail as a rudder. One crewman sat in the cockpit and sailed a compass course for Oahu. Rodgers took bearings three times a day to plot their course.

By the third day, their water was rationed to only a few swallows per man. They’d also picked up a sinister escort: sharks.

That same day they spotted the minesweeper Pelican, but it steamed off without seeing them. Though 18 destroyers had joined the search, a message from Hawaii’s governor to Admiral Moffett captured the general mood: “Whatever their fate…they have upheld the best traditions of the great pioneers of our country.” It seemed the governor was giving them up for lost.

On the bright side, No. 1 covered 50 miles in a single day, averaging 2 knots per hour. Unless they ran into a storm, Rodgers felt confident they’d eventually reach Hawaii. At one point a light rain fell, which the men soaked up with a cloth, but it was hardly enough to satisfy their thirst. Whenever they picked up a ship’s radio bearing, Rodgers steered the plane in that direction. They never managed to catch up with the search parties, however, and when the seas turned rough they were forced to take down their sail.

Stantz worked night and day to build a rudimentary sending set, helping keep their hopes alive. He did eventually manage to get one message out that was picked up by a search vessel. But the ship’s crew couldn’t make out the details, so no one realized it had come from Rodgers’ plane.

On September 5, the aircraft carrier Langley arrived on station and began launching pairs of search planes. It was now a week since Rodgers and his men had left San Francisco. Their water supply had run dry, and the men were so weak they were reduced to crawling around the plane.

On the sixth day at sea they managed to get the freshwater still working, burning wood taken from the wings’ leading edge. Even so, after five hours they’d only eked out a quart of water. Hope was fading fast among the crew. It didn’t help that they overheard a broadcast saying their plane had probably crashed and sunk.

“Hell, boys, we might be worse off,” Rodgers said, trying to rally his men. “I once knew a man who was adrift for 15 days with nothing but a log under him.” Not everyone shared his optimism, however.

By the seventh day, more destroyers had joined the search and the local aeronautical association posted a $500 reward. But hopes of finding the flying boat had reached the vanishing point.

They were blessed by a heavy rainstorm on the eighth day. The men spread out fabric from the wings to catch the downpour, collecting a couple of gallons. Since the water was contaminated by the fabric’s aluminum paint, they strained it through their shirts before drinking. It tasted lousy, but it was the best water they’d ever drunk.

On the ninth day Stantz heard more discouraging news from the radio. Twenty-one of Langley’s pilots concurred that No. 1 had “sunk and the search should be discontinued.” As it happened, the PN-9’s crew sighted Oahu’s north shore that same afternoon. But when the wind shifted and they couldn’t make their way to land, the men’s spirits reached their lowest ebb. “It was too much,” Bowlin recalled. “I was ready to call the sharks and say, ‘Come and get me any time you’re ready, boys.’”

All was not lost, however. Analyzing their problem, Connell tore up the plane’s metal flooring to fashion leeboards and lashed them together with control cable. Soon they were able to navigate up to 15 degrees on either side of the wind.

Knowing that Kauai, farthest north in the Hawaiian chain, represented their final chance to make land, Rodgers set course for the island. He realized that if they weren’t careful, they could miss Kauai just as they had Oahu and find themselves with nothing ahead save Japan.

As dawn broke on September 10, their tenth day at sea, the crewmen strained to make out Kauai, but it was nowhere to be seen. Could they have missed it? That morning was punctuated with rainsqualls, the horizon shrouded by fog. Finally, at 9 a.m., the sky cleared enough for them to spot Kauai on the horizon, right where Rodgers had plotted it. “It was a wonderful sight,” said Connell. Now all they had to do was reach land.

The submarine R-4 was about 15 miles off the southeast coast of Kauai when an officer on watch spotted something in the distance. At first he thought it was a sampan, but as the sub drew nearer he recognized it was actually a flying boat. When the sub’s crew asked the aircraft to identify itself, the response was stunning: “PN-9 No. 1 from San Francisco.”

As R-4 came alongside, all five crewmen stood atop the upper wing, waving. Their clothes were torn and dirty, their faces darkened by 10-day beards. “Do you want to come aboard?” asked the sub’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Donald R. Osborn Jr. “No,” Rodgers replied.

Bowlin later explained: “We didn’t want to be picked up. We were only 15 miles from shore and heading in nicely. It was our ambition after sailing nearly 400 miles to complete the rest of the journey under our own power.”

Rodgers asked the sub crew for food, water and cigarettes, then informed Osborn he intended to sail the rest of the way into the harbor. When the sub commander insisted the PN-9 be towed instead, Rodgers shot back: “No! Stand by in case we miss the harbor.”

Deciding the men must be out of their heads, Osborn was about to have them physically removed when Rodgers finally admitted his crew was too weak to swim ashore if anything went wrong. “Let them tow us in,” Rodgers conceded. “Any ship takes a pilot going into harbor.”

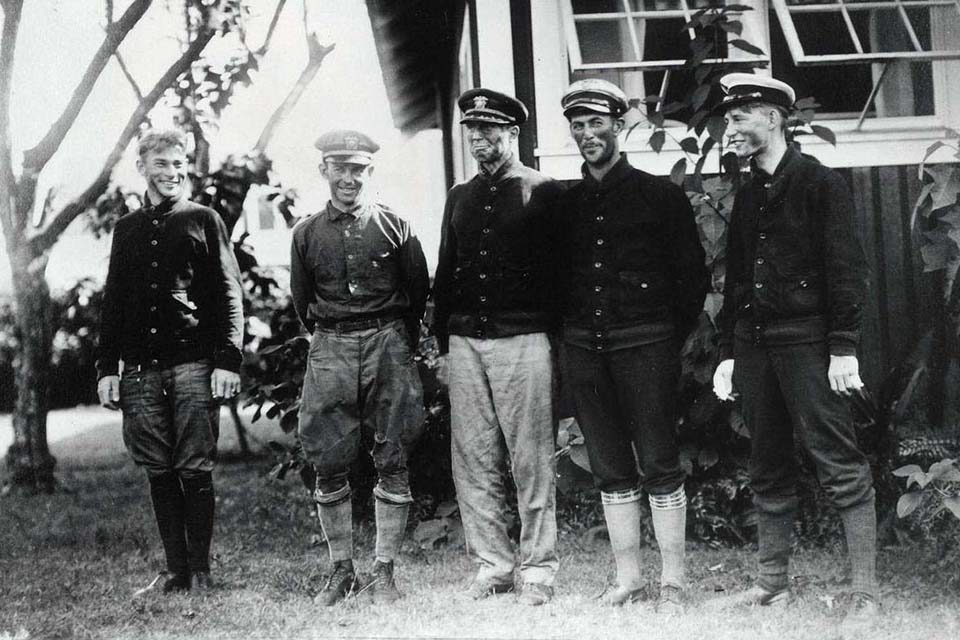

Once the crew reached shore, Rodgers asked that they be photographed before they had cleaned up. The picture shows them smoking cigars as they stand in line, grinning. A reporter described them as looking like hobos—not surprising given their appearance.

A flood of messages soon arrived from around the world. Navy officials, politicians, foreign governments and the public all clamored to have Rodgers and his crew appear at functions in their honor. San Francisco feted the men with a parade, and Rodgers and Connell were deluged with offers for their stories. Newspapers nicknamed Rodgers “Navigatin’ John,” and Honolulu wo men named their sons after him.

In hindsight, even if Aroostook’s crew hadn’t given No. 1 erroneous bearings, the flying boat’s port engine wasn’t operating efficiently enough and the tail winds were insufficiently strong for Rodgers to have flown nonstop all the way to Hawaii. But the PN-9 had gotten them within 400 miles of their destination, and they set a new world distance record for nonstop flight by a seaplane.

As a reward, Rodgers was appointed to the Bureau of Aeronautics. Unsurprisingly, he was not well suited to desk work and lasted only seven months in the job.

On August 27, 1926, Rodgers flew from Washington to the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia to inspect two new P-10s that he hoped to use for a second attempt at a nonstop flight from California to Hawaii. En route, his plane plunged into the Delaware River, where he remained trapped for an hour. Lieutenant Connell, who had been waiting for Rodgers at a nearby airfield, pulled him from the wreckage. Rodgers died a few hours later—almost a year to the day after he had set out from San Francisco on his record-breaking feat.

Rodgers’ California-to-Hawaii flight represents one of the greatest accomplishments in early aviation history. That challenging passage not only demonstrated the Navy commander’s incredible resourcefulness, it also helped lay the groundwork for commercial flights over the Pacific. Honolulu would name its international airport after him, and in 1942 the Navy christened a destroyer USS John Rodgers.

Today the floods of tourists who vacation in Hawaii each year owe a lot to Commander John Rodgers, who paved the way for all who followed. They have him and Admiral William Moffett to thank for the foresight and heroism that made crossing the Pacific a matter of routine.

John J. Geoghegan is the author of Operation Storm and the executive director of the SILOE Research Institute in Woodside, Calif. For further reading, he recommends Above the Pacific, by William J. Horvat.

Originally published in the March 2014 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.